- In times of war people behaved, though!

- Fifteen days it was the book of Urgain that gave greater name to Jose Antonio Loidi Bizkarrondo. Last year he spoke on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of the writer in the Baztan Black Novel Week of his sister Anjelita Loidi. From the very moment we realized that the 100-year-old had already had a lot to say he was trying to make his brother known.

101 urte betetzera doa abuztuan. Botikaria izan da lanbidez –Pasai Donibanen lehenik, eta Donostian gero–, gerra ondoan ikasketak bukaturik. Errenterian zinegotzi abertzale zuen aita –alkate, gero–, eta haren ibili politikoak agindu zuen familiaren biziera gerra garaian. Anjelitak kontatu dizkigunak dira lekuko. Esankizun dira botikan ikusi eta entzun dituenak, eta esankizun, halaber, bidaiari porrokatuarenak, 90 urte beterik ere Yemen, Uzbekistan, Armenia eta batean eta bestean ibili baita. Lehenago, berriz, munduan diren eta ez diren bazterrak korrituak zituen.

His father, Florentino Loidi, was an Abertzale councilor when the war broke out in Errenteria.

Historian Mikel Zabaleta has made the history of our family from 1834 until the death of his father in Irun in 1955. Before the war, the father was deputy mayor of Errenteria, of the PNV. When the war came, we went on an excursion to Bizkaia. On the way we were first in Aizarna [Zestoa]. From there, to Ispaster, to Bilbao and, finally, to Trucíos. When we were in Bilbao, the Republican mayor of Errenteria was taken away or something they did and my father had to be the mayor. He was mayor of Errenteria, when we were in Bilbao; we would say he was “mayor of exile.”

Did you leave Errenteria and went to Bilbao, your mother and your brother José Antonio?

Yes, with my father. And for example, the father was in Gernika when the bombing took place. At that time we were in Ispaster, in the Arritola Manor, near Ereño. Arritola was owned by a resident of Bilbao, who used it in summer, and was requisitioned in the war, according to the same source. There we got all the bombing. The airplanes would come, they would come to us and turn around. All of a sudden, the airplanes, we in the garage, were kept in the pit, and we saw that pieces of white paper were being thrown out. When they left, we went out and saw what he put on the papers: When your neighbor’s beards see you peel, put yours to soak.”

What do you understand?

To walk carefully, they're going to throw away the bombs. The airplanes didn't come. The victim's father had a car and shared it with the mayor of Ereño, Biritxinaga. They were going and coming to Bilbao. The day Gernika was bombed, my father didn't show up! Apparently, when they returned from Bilbao, it was the first bombings that reached and took refuge in the sewer. Subsequently, the march continued, and the second bombing hit the victims in the Rentería district of Gernika. Then they left the car at the corner of the road and they went up the hill, where they saw the second aggression, the fire bomb, between pines. We were worried because we saw smoke from Gernika. In the afternoon he arrived late at Arritola, leaving Biritxinaga in Ereño.

Your father told you about the bombing of Gernika.

And the next day the troops entered Lekeitio. They had radio in the neighborhood, and so we found out we weren't safe, so we took the car and we went to Bilbao on two trips. We left around two in the morning. The first trip was made by his parents, along with Joxe Antonio and his brother. Meanwhile, I stayed in Arritola with about seven guys: Koldobika Mitxelena, the brothers Luis and Julio Arozena, Boni Olaizola, my cousin Jose Mari Loidi, and Ximon de Mutriku.

You were in Gernika the day after the bombing.

The next day, yes, in the early morning. Everything was dirty. In Gernika he was not separated from the house and from the street… From there to Bilbao with his father. Did you meet Joseba Leizaola, recently deceased?

.png)

Yes.

We lived with them. His father was Rikardo, brother of whom Jesus Mari Leizaola was lehendakari. We also had as an uncle Jesus Mari Leizaola of our family, who was Maritxu Loidi. We live in Ricardo's house until the troops almost entered Bilbao. So we went to Trucsos.

The story of war is yours.

And those stories were picked up from me by Pako Etxeberria, from Aranzadi, in the recording. I wanted to hear them. Another thing, the war: the women who had fled from her husband were sent on foot from Zumaia to Bizkaia. When I was young, we had a maid, Bitxori, from Goizueta. He married a mikelete, Zumaiara. In the war, the Miquelete moved to Bilbao and stayed in Zumaia with five children. When the troops entered, they took the women, including Bitxori, and sent them on foot to Lekeitio. Bitxori, for example, had gone with five children; the youngest, was four months old. When we were in Bilbao, we found out how women came to Lekeitio, and there we left my father and I. We saw Bitxori there. We took her and took her to Bilbao, along with her husband. When we went to Trucíos he came with us and helped us at home. There I was the invalid.

You an invalid?

Turtzioz. There was the front and there was the government. Jose Antonio Agirre, Jesus Mari Leizaola… Manuel Irujo was not there, had left for Barcelona. One day, our friend Joxe Migel Etxebeste told us that that farmer in the Basinagre neighborhood had told him that he had a lot of figs and that he was going to eat the fig. It was José Antonio and I, with José Miguel. We got to the farmhouse and Joxe Migel climbed the fig tree and shook it so the figs fell to the ground. As we picked up the figs, the airplanes settled there and started throwing the bomb. They burned the Higo tree. I wore a white and red dress, and as they said that from the airplane you saw the red, I put a blue jacket on top, I leaned and tried to hide the red color. But the shrapnel of a bomb reached my leg. Joxe Miguel took the scarf and made me a tourniquet so I wouldn't lose my blood. I didn't see my brother, and he was worried. “And Joxe Antonio? And Joxe Antonio?" The one who had been by our side until then did not appear.

Where was I?

There was a large hole near him and there José Antonio was kept. How happy I was to see it! They took me in a truck and took me to the resort of Carranza, where they already had the hospital. I have a stain below my left knee. I've got the shrapnel stored. The bomb is shattered and there's usually a lot of hot wind, and the force of that wind raised us up in the air and threw us about two meters from where we were. On that day, in Karrantza, a total of 36 people were killed. For example, the bombs ended the life of the peasant who was in the camp next to us. Since then, the bombing began every day. A few days later, the soldiers left Turtzioz. I remember how they went in front of the house, singing the Eusko gudaris. There were Amaiur, Loiola… and other battalions. They went to Santoña, where they were made prisoners.

Anjelita Loidi keeps the letters written by

his father during his flight. Photo: Dani Blanco

Your brother José Antonio said that after the war you were a young man in Orio.

His uncle was not there, but he was his father's cousin, Luis Loidi. They helped us, they behaved very well. They had an empty little house and we walked in. But we didn't have money, Joxe Antonio was sick, and then I looked for a job at Villabona's pharmacy; by then I only had one year left to finish my studies. I lived in Villabona for three years. At the time, there was no mobile phone today, and we were talking about letters. And if something was urgent, at that time we stayed in the town's telephone center and talked about Orio a Villabona and Villabona a Orio. In 1939, they made the so-called “patriotic enemies,” when I finished my studies. But in Villabona we already had a nephew, who was missing a year to finish medical school, and I was told at home to wait. I waited until I finished, did those tests and bought Pasai Donibane's pharmacy. Then there was the Bank of San Sebastian, and the director knew my father, knew my family, and in 1940 he gave me a loan to buy a drug.

You in Villabona, working in the pharmacy, the mother and José Antonio in Orio.

Yes, and my father in France. From Turtzioz he went to Laredo, and in an Asturian town he embarked on an English steam and came to Bordeaux along with many others. From there, to Kanbo. There he was a year, with so many Basques: Azkarraga, Uruñuela… there were a lot of people known. During his stay in Kanbo, a house was set up in Armendariz for children who had left the war, in which he was called the Palace, and was appointed local administrator. He stayed there until the parents of the children left and picked them up. I've kept the letters my father wrote to me.

Pasai Donibane. Photo: Dani Blanco

Last year we heard you tell the story of these letters in the Week of the Black Novel of Baztan (H)ilbeltza.

Ajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajacajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajajaj So we had to write in such a way that nobody could understand it. Vitoria was Sagarra, Madrid was Alarcón, Castillo was Trucios, Teruel was the bags, Clavería was Catalonia… My father also did not sign Loidi; he always used the two surnames “Alkorta”, “Iturzaeta”… and the three. Or “El Arritolano”, that is, because we live in Arritola in Bizkaia. And we did the same thing, we invented names. Then, when the Germans entered France, they refused to send letters here and there.

But, of course, you sent them.

Yes. We had a small cousin at Elizondo, Anita, and he was sending him a letter, but inside there was another one for my father. The cousin handed the letter to a well-known trustworthy farmer who deposited it on a tree like him. The next farmer took the letter and took it to another tree. Thus, the letter reached his father from one side to the other, to Kanbo or Armendariz, sometimes through the mail scam of San Juan de Pie de Puerto or Bidarrai, with the stamp of France.

That was the history of letters.

But one time, a police officer, the one in Spain, caught a letter from me to a peasant. She gave the name of our cousin and Anita had to invent an explanation saying that our father was sick, that there was no politics… I think they believed him, at least we knew nothing else. Of course, we couldn't use this system anymore, and in one way or another we knew that some of the woodworkers were cleaning up the forest in Orbaizeta Goikoa. On the mountain they were against France and would easily pass to the other side, taking letters… In the war there were also people! Otherwise, we couldn't tell each other.

I'm surprised you've kept all this in your memory.

Yes, everyone is astonished. I don't even know how I did it. The last one, they wrote it in the newspaper about me, and in my house they became angry with me: I have two pharmaceutical daughters and two grandchildren, and I was angry because I said I didn't have to take medication to live a long time. Ha, ha… I didn’t intend to tell stories about the war, but… I wanted to tell good news, just good news…

“Gure aitaren historiaz ari diren aldizkarietan gizonezkoen argazkiak dira handiak, eta gureak txiki-txikiak. Ez dakit gizonek gehiago balio zuten, baina badakit gehiago agintzen zutela. Botika aldizkarietan ere lehendakariak gizonezkoak dira beti, eta aldiz, botikarien artean emakume gehiago dago gizona baino. Akordatzen naiz, behin, botikario bilera batean, hasi zen emakume bat zerbait esaten, eta lehendakariak esan zion: ‘¡Tú cállate!’. ‘Zu, isilik!’. Betiko gelditu zitzaidan. Orain ez dira horrelakorik esaten atrebitzen”

“Gerra hasi baino zortzi egun lehenago etorri nintzen Madrildik, aitak lagunduta, Botika ikasketak lau urteak eginda. Han egiten nituen etsaminak, eta aitarekin joaten nintzen. Ez zidaten bakarrik joaten uzten, neska batentzako leku peligroz betea zen Madril. Orain, berriz, Munichera doa iloba. Gauza horiek asko aldatu dira”

Juan Garmendia Larrañaga zena min ohi zen adin handiko nekazaria hiltzen zitzaiolarik. Entziklopedia oso bat galtzen zuela iruditzen zitzaion. Ez zuen Anjelita Loidi Bizkarrondo ezagutu. 101 urte betetzera doana lehen mailako berriemaile da: gerraurreko Errenteria, herriko zinegotzi abertzalea aita, batzokiaren inaugurazioa 1933an, farmazia ikasketak, garaiko Madril, gerra, Gerbasio Albisu apaiz fusilatua, Koldo Mitxelena, Gernikako bonbardaketa, Turtzioz, Agirre lehendakaria, Itxarkundia, Santoña, Baztan… Garai bateko oroitzapen, argazki eta eskutitzen gordailu. Anjelita Loidi Bizkarrondo, Gernika errea oinez igaro zuen emakumea.

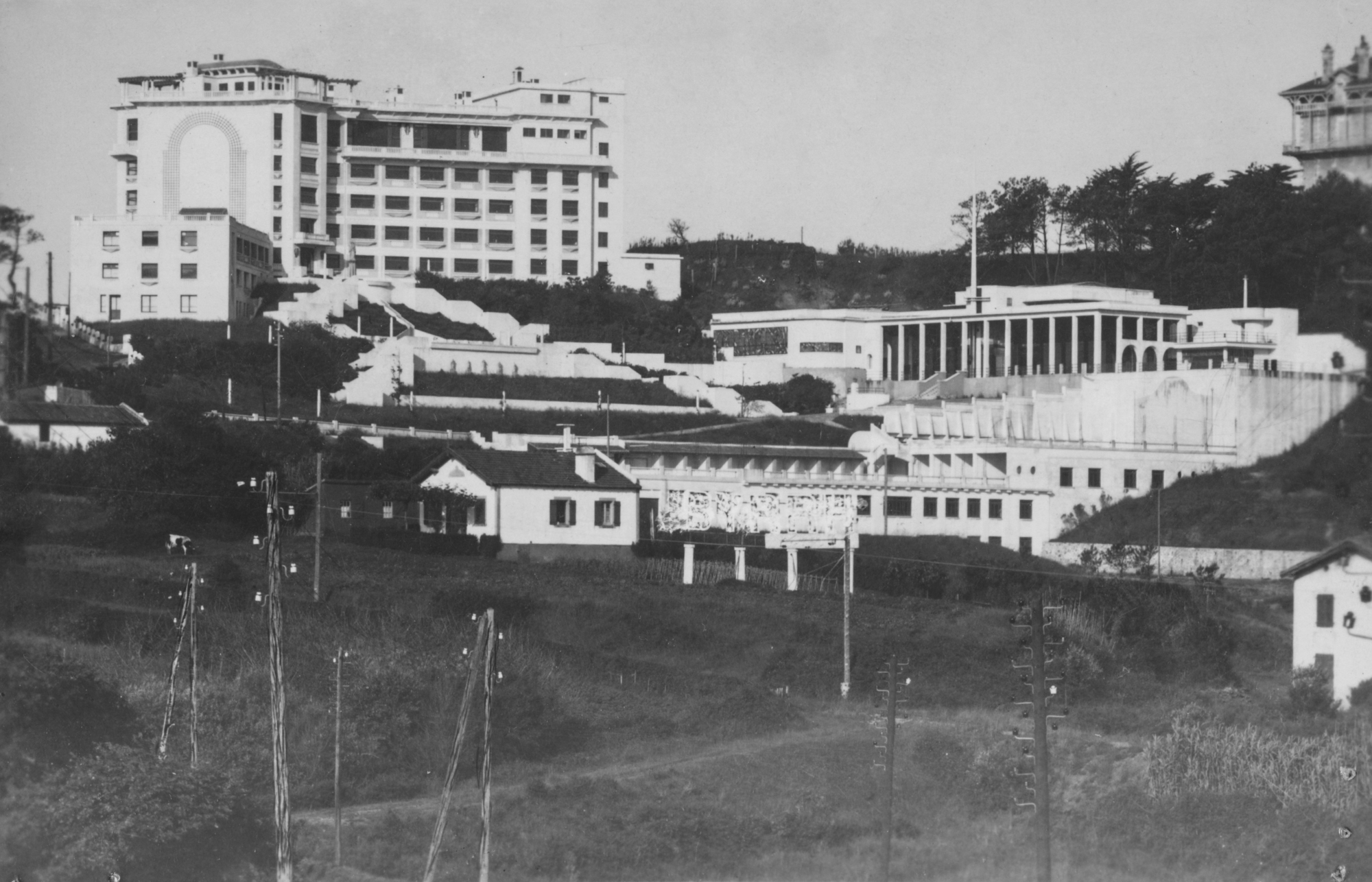

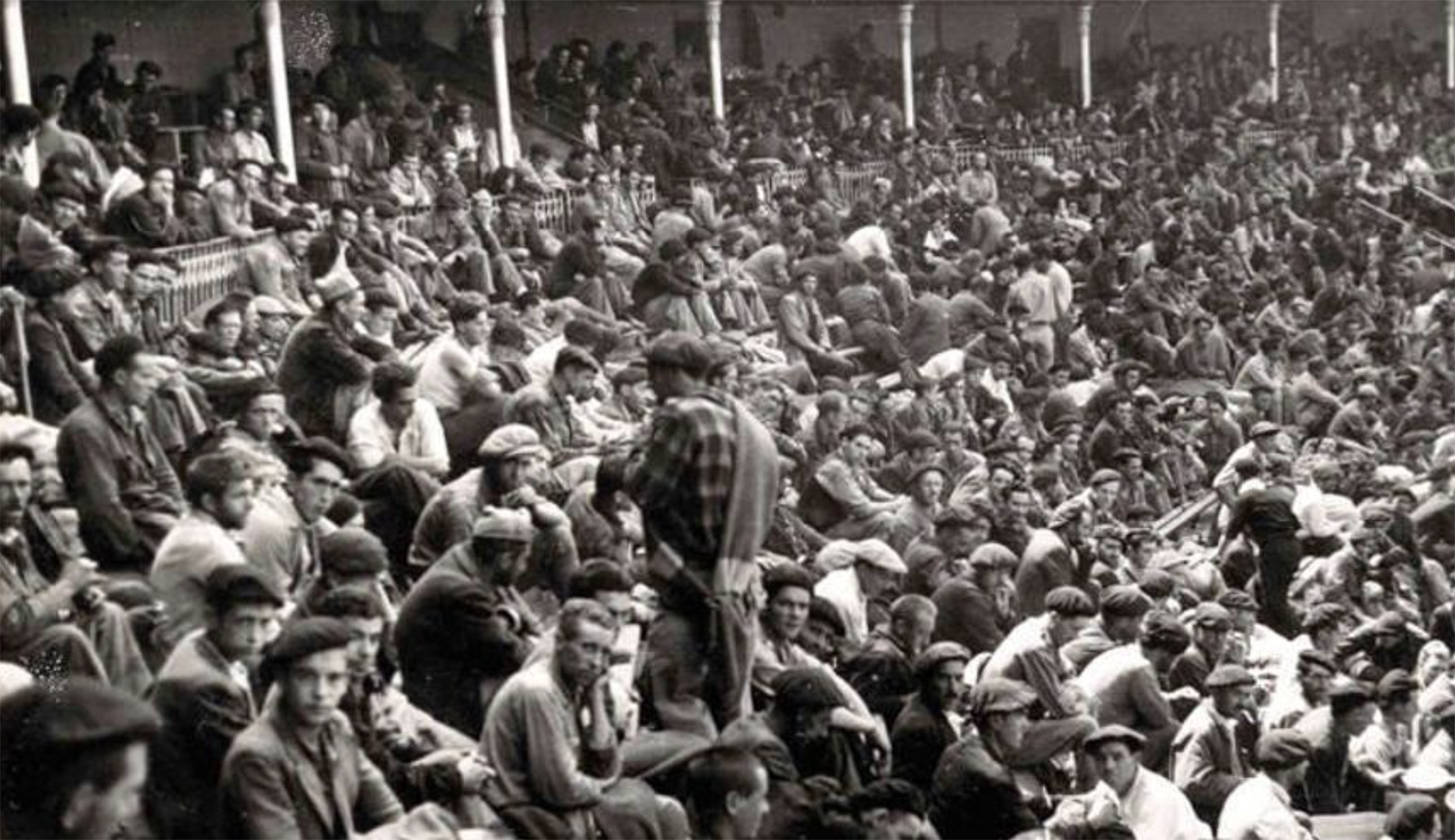

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

Segundo Hernandez preso anarkistaren senide Lander Garciak hunkituta hitz egin du, Ezkabatik ihes egindako gasteiztarraren gorpuzkinak jasotzerako orduan. Nafarroako Gobernuak egindako urratsa eskertuta, hamarkada luzetan pairatutako isiltasuna salatu du ekitaldian.