"If ablation hurts us, let's put aside this part of tradition."

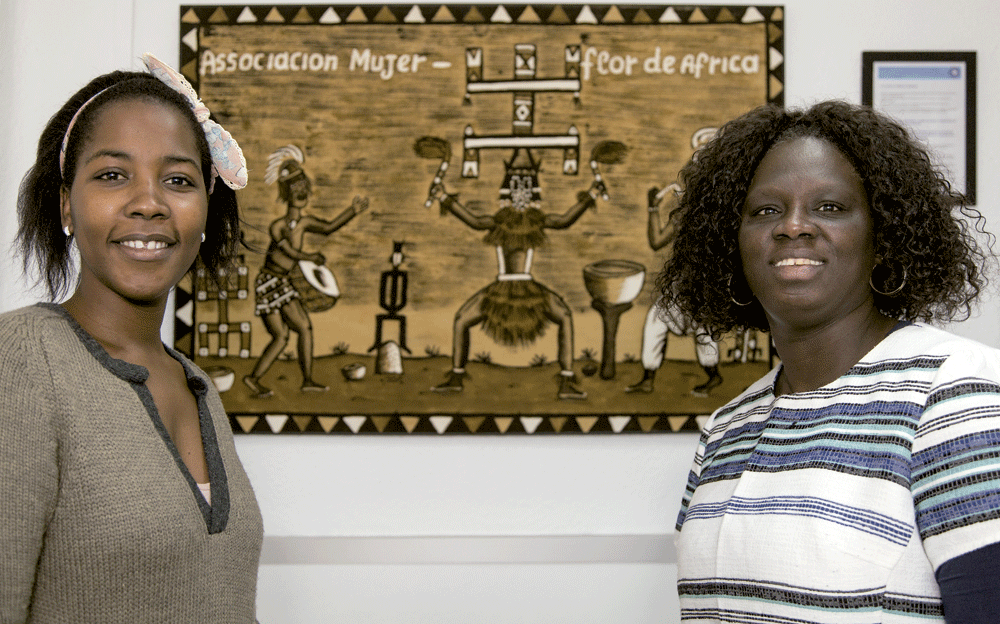

- Fatima Djara does not sell the customs of her country, Guinea-Bissau. But he's not willing to hold it all up. Fight to eradicate ablation, especially in Navarre. He works very carefully, he does not believe that those who practise genital mutilation should be considered criminals.

14 urterekin Kubara joan zen ikastera. Herri-Lan ingeniaritzan lizentziatu ondoren, Ginea Bissaun eta Bruselan bizi eta lan egin zuen. 2005ean, alargun gelditutakoan, Bilbora etorri zen eta handik Nafarroara. Egun, emakumeen mutilazio genitalaren aurkako aktibista da. Munduko Medikuak elkarteko bitartekari dihardu, giza integraziorako goi teknikaria, Nafarroako Berdintasunerako Kontseiluko kidea eta Flor de Africa emakumeen elkarteko sortzailea da. 4 urte zituela ablazioa egin zioten eta bere esperientzia Indomable liburuan bildu zuen 2015ean. 10 urteko Asier mutikoaren ama da.

What was your childhood like?

His father was Ethiopian and Muslim. Catió, natural from the city of Catió, south of the mother. The family met in the capital, Bissau, and there the family was founded. For my mother I had six brothers and there were many of us from my father, but today we only have five. We belonged to a humble family. My father was a fisherman, and when I was 7 years old, he died at sea. I stopped with an uncle and took a boarding school to study. Guinea-Bissau was supported by the socialist countries. For example, they opened schools for the children of those who died in the liberation struggle. I had the opportunity to go there. Then I was in Cuba from the age of 14 until I finished the engineering studies of Public Works. During these years, there were many people in Africa: Sahara, Mozambique, Angola, Sao Tome, Cape Verde, Ethiopia, Sudan… At the end of the studies I returned to Guinea and between 1991 and 2004 I worked in the Ministry of Public Works.

Why did he leave Guinea-Bissau in 2004?

In 2003, the Ministry signed an agreement with Belgium on road maintenance. I went on a course and there I met the girl who helped me perform the reproductive treatment. I was married since 1992 and we wanted to bring our children, but we couldn't. We put everything in place, but when my husband had to go to Brussels to take part in the treatment, he suffered a car accident in Guinea and died. It was a terrible blow. The world had crumbled to me. I went home, and at the end of the mourning, I decided to leave, because I could no longer. I was about to go crazy. After a year in Brussels, my mother told me to go see my sister, who lives in Bilbao. I did. I accompanied my sister with her children, and I began to get to know the movements of African women. I started working with the Women of the World association. In 2008, the Doctors of the World organization brought out a job offer, introduced me, and made a proposal for me to come to Pamplona. Now I'm here, with my 10-year-old son.

What is your job at Doctors of the World?

I am responsible for a programme to prevent female genital mutilation. We want to raise awareness and train the African community living in Navarre. Many have suffered it or know it closely, but they do not regard it as bad. Many women do not admit to having suffered both physical and psychological damage. Because of the education they've had, they think it's good for women to accept pain, not cry, not talk about it. As mediators and as women who have suffered ablation, our job is to show what affects mutilation. We've had that, we've heard the same things, and we want to tell you that everything is a false myth. We don't want to blame our fathers and mothers, our elders, but we have to make social change. If mutilation hurts us, we can dispense with this part of tradition, and we will continue with everything else, so that the habit is beautiful and beneficial to all.

What services do they offer?

We offer a service to help women to go to the doctor, for example. We also work a lot with men. They often do not know what it is and compare ablation with the constituency of men, but it has nothing to do with it. The woman is stripped of her clitoris, the flesh, and not a piece of skin. In the workshops, we teach them through the reproduction of the vagina what mutilation is and they get frightened.

We train professionals who work with Africans. Doctors, teachers and social workers often don't know how to address the issue, because they don't know the habits and mentalities of Africans. Professionals have to put themselves in the place of others and think about how to say things, without offending what lies ahead.

What have been the most significant advances in Navarre?

In July 2013, the Prevention Protocol was approved, through which all training sessions are held. In addition, families of girls at risk of mutilation must sign a document before going on holiday to their countries of origin, with the promise that they will not be ablated. Upon her return, the doctor analyzes the girls and informs the social services and the juvenile prosecutor's office in case of mutilation. Parents may be sentenced to penalties ranging from 6 to 12 years ' imprisonment. It's a very powerful argument, who is going to keep his family here if he puts his son in jail and sends money to Africa? In addition, we show families how to argue the issue in Africa with their families, but without losing respect.

We do not want to get to this kind of extreme situation, of criminal punishment, because, in our view, those who do ablation are not criminals. All mothers want the best for their daughters, but we must not forget that we are talking about a patriarchal and very traditional society. We cannot judge these people solely from our point of view. It is all very well that all of this appears in the criminal code, but our philosophy, our strategy, is to work in advance to prevent those results.

How do Africans take what you say?

Since we started in 2008, in Navarre, there has been remarkable progress. At first it was very difficult to reach the African community. Seeing that they didn't go to the sessions we organized, we decided to change strategy. We started working on sexual and reproductive health in their neighborhoods and meeting points, with the help of social services. They didn't want to talk. At first they thought I was crazy because I was talking about mutilation and I was sent to the street. Now, instead, if you say you want to talk about that or make a documentary, all women want to participate and put their voice in order to end the mutilation. Here, now, African men talk about mutilation. Many know what it is and the consequences it brings. There is still a lot of work to be done, but let us move on.

What do African women think of the harm of ablation?

The damage is many and terrible, both from the health and psychological point of view. Physical effects depend on the type of mutilation. If it is the ablation of the first type, that is, if the clitoris prepuce is cut, many women do not consider it harmful, because they do not know sexual pleasure. Other problems, such as fistulas or those that may occur at the time of delivery, are not often considered as the effects of ablation. Some relate these physical problems to superstitions. They think they're wrong because, for example, they've taken a look at them. In addition, it is poorly seen to show suffering. If a woman suffers from it, if she is sad, if she falls into depression, people consider her crazy and the family rejects her.

Many women have serious mental health problems.

“We do not want to get to this kind of extreme situation, of criminal punishment, because we believe that those who do ablation are not criminals”

What is the purpose of ablation?

In our model of patriarchal society, ablation is a way to dominate women, a way to control their sexuality. Who says, for example, that white women here or black women who are not mutilated are not clean? Who says that the clitoris can grow out of proportion to become a penis? Who says that a non-mutilated woman can't reach the wedding untouched? Virginity is not linked to mutilation. I'm mutilated, and I didn't get a virgin to the wedding because I didn't want to. And it's over. Fortunately, this way of thinking is rapidly spreading across Africa, and today's young people don't give as much importance to cleaning as they did before.

How does society see here?

I like Pamplona, because it's small. People are cold and welcome the visitor. I don't mean dry, but it's hard to make friends. In small villages, integration is easier, because Africans are in touch and it's easier to meet people.

Navarre, in general, is very conservative. We strive to integrate and foster coexistence, but it is not easy. Now, for example, we're looking for a headquarters for our Flor de Africa partnership, but it's impossible. Black women are asking us for huge prices for local rent. That is why African women are asking for help from the institutions. We want a space to make our culture known, to show it in a positive and open Africa to the whole world.

Can Euskera be a help to integrate?

Of course. I would like to learn Basque, and my son too, but there are no facilities. We cannot help them with household chores and, for example, if a few hours of class were set in the centres, it would be easier with some teachers. Our children are from here and we want them to join. The best way to do this is to learn the two languages here.

How many languages do you know?

Portuguese, French, Spanish and some African languages: on the part of my father I adapt to manding, from mother to pepel and to other languages.

You've published the book Indomable. What is the objective?

I wanted to tell people how African women live. Ablation has been a very painful experience for me. I was 4 years old, but I remember the day I was cut off, and the women around you remember everything when they suffer the same thing. My older sister and I woke us up and told us it would be a great day for us. They took us to the grandmother's house and there they celebrated a great party. They cut us off and then cured the wound. It was very painful and the following days too. The worst thing was to get in, because I was burning.

When they proposed to me to make the book, it was very hard for me, but I accepted it. Journalist Gorka Moreno helped me express my feelings, my pain and my rebellion.

What plans do you have for the future?

I would like to work in Guinea in the future. The Dunia Musso (The World of Women) association works here and in Guinea at the same time. February 6 is Ablation Day and we want to organize a five-kilometer race to speak out about it, without hiding anything. We need the help of businesses and people. There we are working with a group of young people, with whom we are carrying out training courses for trainers and it is doing very well. The goal of the race is for society to see that young people are against mutilation.

“Hemengo jendeari informazioa ematen diogu, bestela izugarrikeria baino ez da ikusten eta pentsatzen dute gu, beltzok, gaizkile basatiak garela. Ez da inor kriminalizatu behar. Milaka urte dituen ohitura odoltsua ezin da egun batetik bestera desagerrarazi”.

“Ablazioak iniziazio erritutik duena ederra da. Emakumeak elkarrekin basora joaten dira jai bat egitera eta han abestu eta dantzatu egiten dute. Adinekoek gazteei azaltzen diete zer den emakumea izatea, nola integratu taldean, nola gorde balore kulturalak… Horri eusten ahal zaio ebaketa mingarria bazter utzita. Tradizioak moldatu behar ditugu”.

Prentsaurrekoa eskaini dute ostegun honetan Marc Aillet Baionako apezpikuak, elizbarrutiko hezkuntza katolikoko zuzendari Vincent Destaisek eta Betharramgo biktimen entzuteko egiturako partaideetarikoa den Laurent Bacho apaizak. Hitza hartzera zihoazela, momentua moztu die... [+]

Antifaxismoari buruz idatzi nahiko nuke, hori baita aurten mugimendu feministaren gaia. Alabaina, eskratxea egin diote Martxoaren 8ko bezperan euskal kazetari antifaxista eta profeminista bati.

Gizonak bere lehenengo liburua aurkeztu du Madrilen bi kazetari ospetsuk... [+]

11 adin txikikori sexu erasoak egiteagatik 85 urteko kartzela zigorra galdegin du Gipuzkoako fiskaltzak. Astelehenean hasi da epaiketa eta gutxienez martxoaren 21era arte luzatuko da.

Matxismoa normalizatzen ari da, eskuin muturreko alderdien nahiz sare sozialetako pertsonaien eskutik, ideia matxistak zabaltzen eta egonkortzen ari baitira gizarte osoan. Egoera larria da, eta are larriagoa izan daiteke, ideia zein jarrera matxistei eta erreakzionarioei ateak... [+]

Elizak 23 kasu ditu onarturik Nafarroa Garaian. Haiek "ekonomikoki, psikologikoki eta espiritualki laguntzeko" konpromisoa adierazi du Iruñeko artzapezpikuak.

15 urteko emakume bati egin dio eraso Izarra klubean jarduten zuen pilota entrenatzaile batek.

Lestelle-Betharramgo (Biarno) ikastetxe katolikoko indarkeria eta bortxaketa kasuen salaketek beste ikastetxe katoliko batzuen gainean jarri du fokua. Ipar Euskal Herriari dagokionez, Uztaritzeko San Frantses Xabier kolegioan pairaturiko indarkeria kasuak azaleratu dira... [+]

Bi neska komisarian, urduri, hiru urtetik gora luzatu den jazarpen egoera salatzen. Izendatzen. Tipo berbera agertzen zaielako nonahi. Presentzia arraro berbera neskek parte hartzen duten ekitaldi kulturaletako atarietan, bietako baten amaren etxepean, bestea korrika egitera... [+]