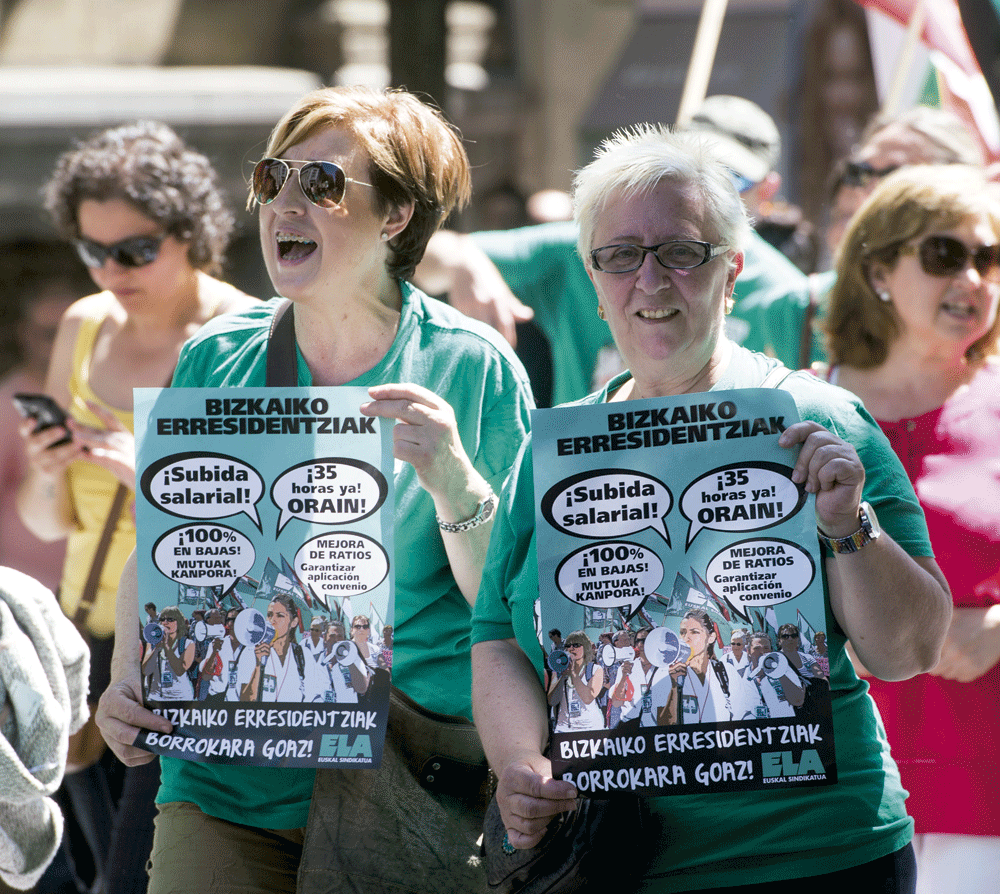

EUR 7,666 less per year

- We are used to the headline: Women are charged below men's wages. It is not that women are paid less for doing the same hours at the same work. And then? Gender segregation and the fact that women are mainly involved in the tasks that are left out of employment significantly affect their professional performance. Thus, according to the statistics of the Spanish and French States, last year the women of Euskal Herria earned an average of EUR 7,666 less than the men at the end of the year, and this year the figure will not change very much.

Why does it cost more to change a light bulb than to serve an old man? How can the handrail win more than the launcher passing through the offices?

Talking about the wage gap is talking about gender inequalities in the labour market, which significantly affect women. In most workplaces, women and men in the same position gain in the same way, because the opposite would be illegal. Structural inequalities are, therefore, at the root of the wage gap: the division of labour according to sex and the almost total fall in domestic and care tasks for women. In the end, today still, because they are the ones who almost always sacrifice working life, among other things, for the care of children and the elderly.

This has spread to stereotypes and beliefs that have diminished the centrality and value of the work performed by women. In this regard, women earn less money at the end of the year because they suffer from the most precarious working conditions and the greatest job instability.

No job, the agent is the worker

As a result of sex segregation, women are attributed certain jobs, considered female and undervalued, both in the economic and social spheres. In other words, jobs considered masculine are better remunerated because they coincide with the male role and the functions performed by women are much worse by the same logic. For example, the man performing maintenance tasks in a supermarket chores more than the woman who makes a cashier in the same place of work, because he needs more physical strength for his work.

Zaloa Ibeas (LAB)

“The crucial thing is not what kind of work is done, but who does it. It’s not that cleaning work isn’t worth a living wage, the problem is that if we have to do women, we deserve it less.”

The head of the LAB women's secretariat, Zaloa Ibeas, has stated that the wage gap is huge even when the job requires the same skill: “What is crucial is not what kind of work is done, but who does. It’s not that cleaning work isn’t worth a living wage, the problem is that if we have to do women, we deserve it less.”

Ibeas stressed that, although the opposite is often heard, there is also discrimination in public administration: “In hospitals, most kitchens are women, while those working with cleaning machines are men and the pay gap is very large.”

Service queens and the poor

The feminization of employment means that the characteristics that have determined women’s lives and work, such as instability or the need to cope with job diversity, are spreading more and more jobs filled by men and women. To say that the world of work is undergoing a process of general feminization does not mean, however, reducing the division of labor according to sex.

In particular, women have the most precarious contracts in the labour market, as they are the majority in the services sector. According to Emakunde, in the CAV, nine out of ten women work in the CAV services. On the contrary, in the sectors that are on the other side of prestige and counterpart, especially in construction and industry, more than three quarters are men.

The entry of women into the labor market has translated into a very precarious commodification of the work they performed, a clear example is the care sector. “Women have entered the world of work according to the interests of the market, without abandoning the responsibility of others. We are not in the same conditions as men, which entails a reduced working day imposed,” explained the LAB worker.

Almost 80% of people with reduced or partial working time are women, and very few voluntarily choose this option. According to Ibeas, “this is the only option offered by the labour market. We are talking about salaries of between EUR 400 and EUR 500, which are impossible to draw up a life plan. Finally, it has the logic of the heteropatriarchal capitalist system, which makes women dependent. Men's wages support the domestic economy and complement that of women. The system must discriminate for its support.”

Unbreakable roof

At the same time as most of the worst paid jobs, women are a significant minority in the highest jobs. The invisible obstacle, the glass ceiling, which prevents access to these positions of responsibility, directly influences the wage gap, since the higher the remuneration, the greater the difference in benefits between women and men. Of the ten executive positions, only three are female and are far from the wages of their male peers. In addition, the 2008 crisis appears to have hardened glass more than ever before.

Ibeas has stated that the tradition of linking command endowments and leadership positions with men is something that is highly interiorized in society, and the resistance of women to power remains evident, whether they are entrepreneurs or directives of a children's school. Furthermore, reaching a position of responsibility does not make the same sense in one sense or another. She says that women who come to senior positions have more pressure, that they constantly need to prove that they deserve a position.

The position of responsibility often means putting employment above all else, such as being willing to meetings at short notice, and many women cannot, if there is no one in the area who takes care of domestic tasks and care. For this reason, in order to gain access to employment and to domestic and care tasks, more flexible jobs need to be accepted.

Ibeas pointed out that, without forgetting discrimination, many women are not prepared to submit to these demands of the labour market because it is not compatible with those that prioritize putting life at the centre.

The shadow of the house to work

Many women lead to work in the shadow of the house and the family. The fact that almost all of their private responsibilities are attributed to them makes the balance between personal and working life very difficult, and when they reach a certain age, many people disrupt their professional careers. One of the reasons why the wage gap has increased since the age of 35 is that in many houses the time comes to take care of children and the elderly.

Women accounted for 95.5% of the people who took advantage of the measures to reconcile work and family life (maternity and paternity leave, reductions in working hours or family care surpluses) in 2014, according to data from Emakunde. Men only 4.5%.

Emakunde’s wage gap: actors and indicators point to the perception that women put their family above employment. By abandoning working life for the care of others, men's employment gains more value and relevance than men's. Therefore, family protection of one and the other is not comparable, as in economic terms, in terms of motivation and hope.

Illegal machismo

Even if it is illegal, there are still companies that have policies that are directly chauvinistic, which pay less to women for the same work as men. Ibeas has told the situation once reported by the union: “In a catering that prepared school food, the men who were in the kitchen gave them 200 euros more in an envelope than the women who worked in the same work. After the complaint, instead of handing it over to the women, they took it off to the men and mounted a magnificent copy. Discrimination is very straightforward, it may seem incredible, but they are still.” It says that many companies cover direct exclusions such as those held, with additional salaries, with a distribution of pluses, a very common practice in the workplace.

Ibeas has also set an example of this intense machismo as another significant case that has occurred after the crisis: “In a company that made fresh cheese in Navarre, women worked in the chain. At the time of the crisis, they were dismissed to hire unemployed men in the village, and directly, they raised their salaries and improved working conditions.” It has also stated that it has been possible to see how working conditions are improved by incorporating men into feminized sectors, such as telemarketing.

Bump of numbers

We have analyzed the causal factors of the wage difference in search of a more complete picture. The data, however, are there and reflect the discrimination suffered by women in the labour market: In Euskal Herria, women earned an average of EUR 21,453 last year, which is EUR 7,666 less than men. In other words, women should earn 26.3% more to access the wages of their peers, according to the Basque Country Economic and Social Development Observatory, Gaindegia.

With regard to the Spanish and French states, the coordinator of Gaindegia, Imanol Esnaola, said that the situation in Iparralde is stronger: “The French State has social protection elements such as the minimum wage of EUR 1,200 and another culture and legal guarantee for family, unemployment or poverty benefits. This entails greater social cohesion in the North than in the South, more dignified living conditions and greater promotion and support for people’s education.”

Turning to the figures, point by point there are

details:By age, the wage gap between young people entering the labour market is smaller. However, once past the barrier of 35 years, it only grows when wages begin to grow higher and when the time comes for childcare and later for parents. The highest wage gap between women and men active in the labour market is among those over 55 years of age os.En in the sector, the wage gap is the lowest in

sectors with fewer women, such as construction or industry. However, in the feminized service sector, the gap is wide. However, Esnaola points out that in the CAV, according to data provided by EUSTAT, the most industrialized counties are those with the highest wage gaps, with a difference of 51% in the Goierri. The exception has been given by the Alto Deba, because of the commitment of cooperatives. As working

conditions improve, wage discrimination increases. Thus, the wage gap between casual workers is narrow and between those with a fixed contract is high. Regarding the duration of the contract, in the Basque Country 79.5% of the partial employment is performed by women, while in temporary employment they also predominate, 54.3%. Both, five or six points above the European Union average.

As working conditions improve, wage discrimination increases. Among casual workers, the wage gap is narrow among those with a fixed contract.

Esnaola sees in the formation the hot pot of income segregation, in a training course based on sex. Women are employed in training branches to operate in sectors with lower economic recognition and men in professions with higher economic efficiency. He believes that culture is very alive. Thus, in the CAV, engineering and architecture studies are chosen by one in four women, while health sciences studies are three in four.

Keys to breaking segregation

“Women who are currently quoting at low levels, what will they pay for when they reach retirement age? What direction will honest women engaged in modest economic activities with high qualifications take?” According to Esnaola, the forecasting system for a few years has red lights in sight. It has advanced that the face of poverty of the elderly will be female and that in order to cope with it, it will be key to strengthen the presence of women in the sectors of greater economic efficiency.

Otherwise, despite the fact that in the coming years there will be economic strengthening, the situation will hardly change, as women are not oriented towards industry. On the other hand, Esnaola considers it important to increase economic efficiency through economic promotion in the sectors with more women.

For Ibeas and Esnaola, the legislation that is adopted with respect will be key to changing the situation. Esnaola calls it a “country pact”: “If we considered it as a people, care, motherhood... in our labor relations would not be an obstacle to the professional career and would be very protected.” But Ibeas says that the trend is the opposite, as the cuts in care are more and more frequent.

Occupational and economic segregation by sex should have an impact on multiple levels; direct discrimination, job evaluation criteria, gender stereotypes and corporate culture, among others. Furthermore, under the glass ceiling, subordinated working life will be guaranteed for women of the following generations.

Prentsaurrekoa eskaini dute ostegun honetan Marc Aillet Baionako apezpikuak, elizbarrutiko hezkuntza katolikoko zuzendari Vincent Destaisek eta Betharramgo biktimen entzuteko egiturako partaideetarikoa den Laurent Bacho apaizak. Hitza hartzera zihoazela, momentua moztu die... [+]

Antifaxismoari buruz idatzi nahiko nuke, hori baita aurten mugimendu feministaren gaia. Alabaina, eskratxea egin diote Martxoaren 8ko bezperan euskal kazetari antifaxista eta profeminista bati.

Gizonak bere lehenengo liburua aurkeztu du Madrilen bi kazetari ospetsuk... [+]

11 adin txikikori sexu erasoak egiteagatik 85 urteko kartzela zigorra galdegin du Gipuzkoako fiskaltzak. Astelehenean hasi da epaiketa eta gutxienez martxoaren 21era arte luzatuko da.

Matxismoa normalizatzen ari da, eskuin muturreko alderdien nahiz sare sozialetako pertsonaien eskutik, ideia matxistak zabaltzen eta egonkortzen ari baitira gizarte osoan. Egoera larria da, eta are larriagoa izan daiteke, ideia zein jarrera matxistei eta erreakzionarioei ateak... [+]

Elizak 23 kasu ditu onarturik Nafarroa Garaian. Haiek "ekonomikoki, psikologikoki eta espiritualki laguntzeko" konpromisoa adierazi du Iruñeko artzapezpikuak.

15 urteko emakume bati egin dio eraso Izarra klubean jarduten zuen pilota entrenatzaile batek.

Lestelle-Betharramgo (Biarno) ikastetxe katolikoko indarkeria eta bortxaketa kasuen salaketek beste ikastetxe katoliko batzuen gainean jarri du fokua. Ipar Euskal Herriari dagokionez, Uztaritzeko San Frantses Xabier kolegioan pairaturiko indarkeria kasuak azaleratu dira... [+]

Bi neska komisarian, urduri, hiru urtetik gora luzatu den jazarpen egoera salatzen. Izendatzen. Tipo berbera agertzen zaielako nonahi. Presentzia arraro berbera neskek parte hartzen duten ekitaldi kulturaletako atarietan, bietako baten amaren etxepean, bestea korrika egitera... [+]