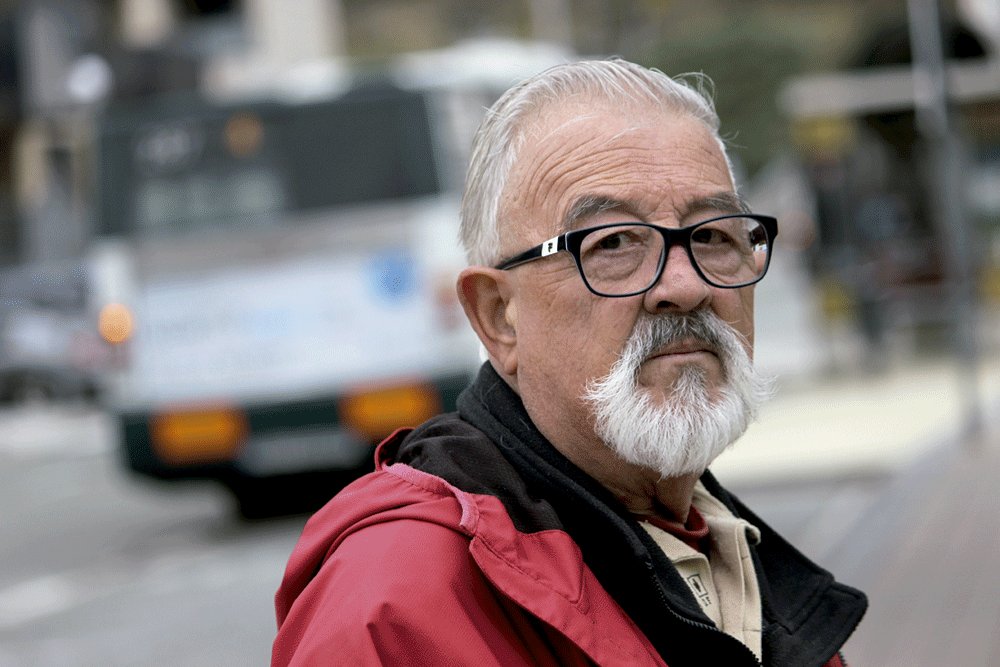

"It was also fun to hide from police custody"

- Its origin is punishment, as the Feliu Dord family arrived in Pamplona punishable by war. For many years, Juan Mari has known prison and exile, helped by nationalism. Along with these sanctions, the mountain has been awarded, as its parents were born in the French Alps and in the Catalan Pyrenees...

Euzko Gaztediko kide eta Iruñeko Eusko Bazterrako sortzaileetakoa 1967an. Urte hartan bertan preso hartu zuten Andeetan ikurrina jartzeagatik. Berriro sartu zuten kartzelan 1968an, ikurrina Urbasan paratzeagatik. 1970ean erbesterako bidea hartu zuen. Mugalde inprimategia ireki zuen Jean-Mixel Larzabalekin batera. Bi atentatu izan zituzten. 1977an itzuli zen Iruñera betiko. PNVko zena, EAkoa izan zen gero. Eskalatzaile, mendizale eta eskiatzaile trebea, hainbat liburu, artikulu eta argitalpenen egile da. Memoriak idazten ari dela utzi dugu: “Euskal kausa eta mendizaletasunaren artean”…

Feliu Dord… you’re from here, you’re Catalan…

I was born in Pamplona, in the Motxuelo neighborhood. My mother was French, from Savoy, from the Alps; my Catalan father, from the Pyrenees. They met in Manresa and got married there. His father was from ERC, a councilman of Culture of Manresa in times of war, and when the withdrawal arrived in 1939 he went to Northern Catalonia along with officials and politicians. For two years I walked from one side to the other, while my mother, my grandparents and most of my brother were in San Sebastian, sheltered by their relatives. His father returned to Manresa in 1941 through some of his inhabitants, but was sentenced to live 200 kilometres from Catalonia. They settled in Pamplona and I was born there.

History of war!

My father was quiet with fangs. You've seen it furious. When the Andes happened, I would see him truly furious. The civil guard didn't leave me alone, he arrested me again and again. The last one, the tricorns, came because I didn't pay 25,000 pesetas. My father faced them and almost drove me to jail. On that occasion I stayed in the pit for three days. The PNV picked up the money, paid the fine and left. I don't have to say it because when I got home, my father put me to chat with me. He told me that a small fire came from my childhood, that at six or seven years I asked him what language our neighbors were talking about. The neighborhoods were called Orkin, with the name “pelotaris”, since at home there were some who were pelotari. They spoke in Basque, and my father told me they were walking in a prehistoric language, and that surprised me a lot. That language, of course, was the Basque language.

The mother of the Alps, the father of the Pyrenees, is inevitable that you are a mountaineer.

It is not difficult! Before me, most of my brother, Marcos, started in Oberena, and from his hand I went to that club at the age of thirteen. In the mountain, at noon, the angelus prayed. And back, on the bus, the rosary. That was too much! In the end, we moved to the Club Deportivo Navarra, and there was something else, there we sang Internacional, Marsellesa and Boga boga. On the other hand, the most complicated mountaineers took maps and translated the toponymy into Basque. So my little fire went on and a lama was made on the mountain.

The small fire made the lama… Wasn’t it the one that broke it?

There's always somebody. We had a neighborhood that really appreciated us. It was Periko Ezkurdia. Abertzale, president of the PNV of Pamplona before the war and later a member of the Alava network. He had a furniture factory, Juan Ajuriagerra sent him propaganda packages and Periko hid it between a wooden mound. Periko learned that some of us met Claveria and García Falces at Jorde Sarasa's house, talking about his Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País. I was soon asked if I wanted to work for the Basque cause García Falces and Periko.

What was it like to work for the Basque cause?

That Association of Friends was nothing more than a shield from the PNV. It was 1964, and the group of young people who were going to those talks went to the Bergara Aberri Eguna the year after. Meanwhile, those young people, Gotzon Bergerandi, Fernando Bara, Martine Iturralde… we talked about this and that, we went to the mountain and met some young people from the Duranguesado. They said they were from Euzko Gaztedi, right? They wanted contacts with the people of Navarre and so we got tangled up. At that time, the marriage José Antonio Urbiola and Mirentxu Oiarzabal returned from Paris to Pamplona, and soon I was at the Napar Buru Batzar. Our job was to bring together young nationalists from Pamplona and Navarra. On the one hand there were intellectuals – Claveria, Sarasa, Elena Gereziaga, Gurrutxaga –, the Euskaltzales – Diez de Ulzurrun, Cortes Izal… – and these young entrepreneurs, Urbiola, García Falces, the Intxausti sisters of Uztaritz and others. We participated in the meetings of the Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos, but, on the other hand, the young people met at Gurrutxaga's house, with Ezkurdia and Santiago Alonso. And in 1967, we founded Euzko Bazterra.

What was Euzko Bazterra?

Youth section of the Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos. We'd be about 120 people, some college students -- Patxi Zabaleta, Manterola, Testo-Izko -- but also mountaineers. We formed the section and started organizing conferences, projecting Mother Earth and the Ball, distributing propaganda in secret, and finding mockery for those who fled the police. I recall that in 1967 Elias Antón, Iñaki Mujika and Baserri, alias, arrived in Pamplona fleeing Gipuzkoa and thanks to them the activities were strengthened. They were from Euzko Gaztedi and were in Pamplona until that of Urbasa.

What do you have about Urbasa?

We placed a great ikurrina in Urbasa on the eve of the 1968 Aberri Eguna. I was arrested and judged in the company of four others. In addition to that, I was accused of having put another ikurrina of Bi Haizpe last year before the Aberri Eguna of Pamplona, many other posts in the church towers, of having passed propaganda from one side to the other of the border… To prison!

He believed that Urbasa's was an artifact that had placed Spain on the Cycling Tour.

That was also in 1968, but later. The explosive made a big hole in the road and the cyclists had to stop. The demonstrators did not abandon Itzulia, which became an event of great shock to the international media. Some members of the Napar Buru Batzar knew where the attack came from, while others did not know. It was a complete mess and, of course, repression. However, some did not give up, and they tried until 1969 when Alberto Asurmendi and Jokin Artajo died.

On the eve of the 1969 Aberri Eguna, when the bomb exploded in his hands. You met them both.

I didn't know them! His death had disrupted everything. I myself brought them among us. Asurmendi was entirely open. Artajo, on the other hand, was quieter. They were from Euzko Gaztedi. At that time, the use of violence by Euzko Gaztedi was a way of telling those of ETA that we were also fighting, violently, but without kidnapping or killing anyone. When the two friends died, everything changed. However, I realized it later, because at that time I was imprisoned in Carabanchel. He had been in jail for eight months.

We know that you were arrested more than once, and that the first Basque expedition in the Andes also had consequences.

We put the ikurrina in Atunrun in 1967, a peak that no one had climbed until then. He was the Navarro representative on the Basque expedition, and I myself brought the ikurrina. It was given to me by Euzko Gaztedi of Durango when they knew that we were going to the mountains of Peru. “Come to Durango, Juan Mari, but only you.” When I left, they gave me the ikurrina and told me. “Meet him at that summit in America!” Me too! On the return, when I had occasion, I handed over the ikurrina to Manuel Irujo in Baiona, representing the Basque Government. Irujo said: “Take that typewriter and write the story of this ikurrina. We keep it in a closed envelope. When the Basque Country is free, they will know the feat you have done.” Not in vain. The police learned this in less than three months. We came from Atunraju and made several projections, and in one of them, unconsciously, we showed a picture of Ikurrina. The whistleblowers saw what they didn't have to do and the indictment. We were arrested for all of the expedition, but since I took the ikurrina, I took care of it. Until then we had been nothing more than recognition, a reward and a medal, but then a punishment.

"At that time, the use of violence by Euzko Gaztedi was a way of telling ETA's that we were also fighting."

Amnesty International proposed to you the appointment of “Prisoner of the Year”.

They wanted us to make a war council, but it didn't. We made muti in jail and I got 40 days in the punishment cell. The German branch of Amnesty International was committed to this appointment – particularly by the Atunraju ikurrina – but in mid-April 1968, when I left prison, I told them that they had to appoint another person, as there were high-level human prisoners in prison. I went out to the street, but the chase didn't end. Mikel Erdozain and I, imprisoned with me, were very vigilant. One brigade from the General Directorate of Security in Madrid, and one of the civil guards, were watching for several months. It was also fun to avoid policing and civil guards. Like a mouse and a cat, we went like that. Anyway, without the “mouse” my nickname was “the lizard”, and so I walked, escaped. And despite all the care, in 1970, I moved across the mountains to four friends I met in Carabanchel. Then he would receive the postcard from the Eiffel Tower. It was our code: it indicated that they had gotten well.

In 1970 driving Carabanchel's friends to the other side, you were soon on your way.

Several falls occurred at the end of the same year. So my girlfriend María Luisa [Mangado] and I hid. First we were in Donostia. She was kept by María Luisa Gerardo Bujanda. I was in the house of Idoia Estornés and Josean Aiestaran, who started with a honeymoon. While I was there, I had the help of the Intxausti sisters to move to Iparralde. The day came true, and my brother Andoni and my two companions accompanied me to the hill of Petretxema, and from there I went down to Laskun with Andoni. We were awaited by Ernesto Torio, from the Napar Buru Batzar, who took me to San Juan de Luz. Then there would also be Maria Luisa, accompanied by her brother Pello and her sisters Ziga.

He worked at the Mugalde printing house in Hendaya, from the train station.

Printing house of the Argoiti family. We had Segundo Marey, who years later was abducted by the GAL, believing it was Peixoto. As usual, another worker, Jean-Mixel Larzabal, proposed to me to start working on our own, that is, to create our own printing press. We could, but we didn't have money. At the time, Felipe Huarte was kidnapped by ETA. I remember that in San Juan de Luz was Jesus Aizpun [founder of UPN in 1979], to negotiate on behalf of the family. The fact is that shortly after the liberation of Huarte two ETA militants arrived in Hendaia, and they found our intention of printing interesting. One was a wealthy family, and we can get ten million pesetas from there, because they made us the money transfer. So we opened the printing press Mugalde working for PNV, ELA, cultural associations and so on. We also edited three porn books at the request of a Hendaya sex-shop.

Where did you get the money from?

According to the ABC newspaper in Madrid, Mugalde opened up with Huarte's money. We didn't know where it came from, but we didn't listen to the ABC. Finally, the Basque Spanish Battalion placed the bomb and detonated Mugalde. The bomb was launched on 23 April 1975 and launched by eta. A month later, on 21 May, he again attacked the remnants of the printing press in Afghanistan.

It's over then.

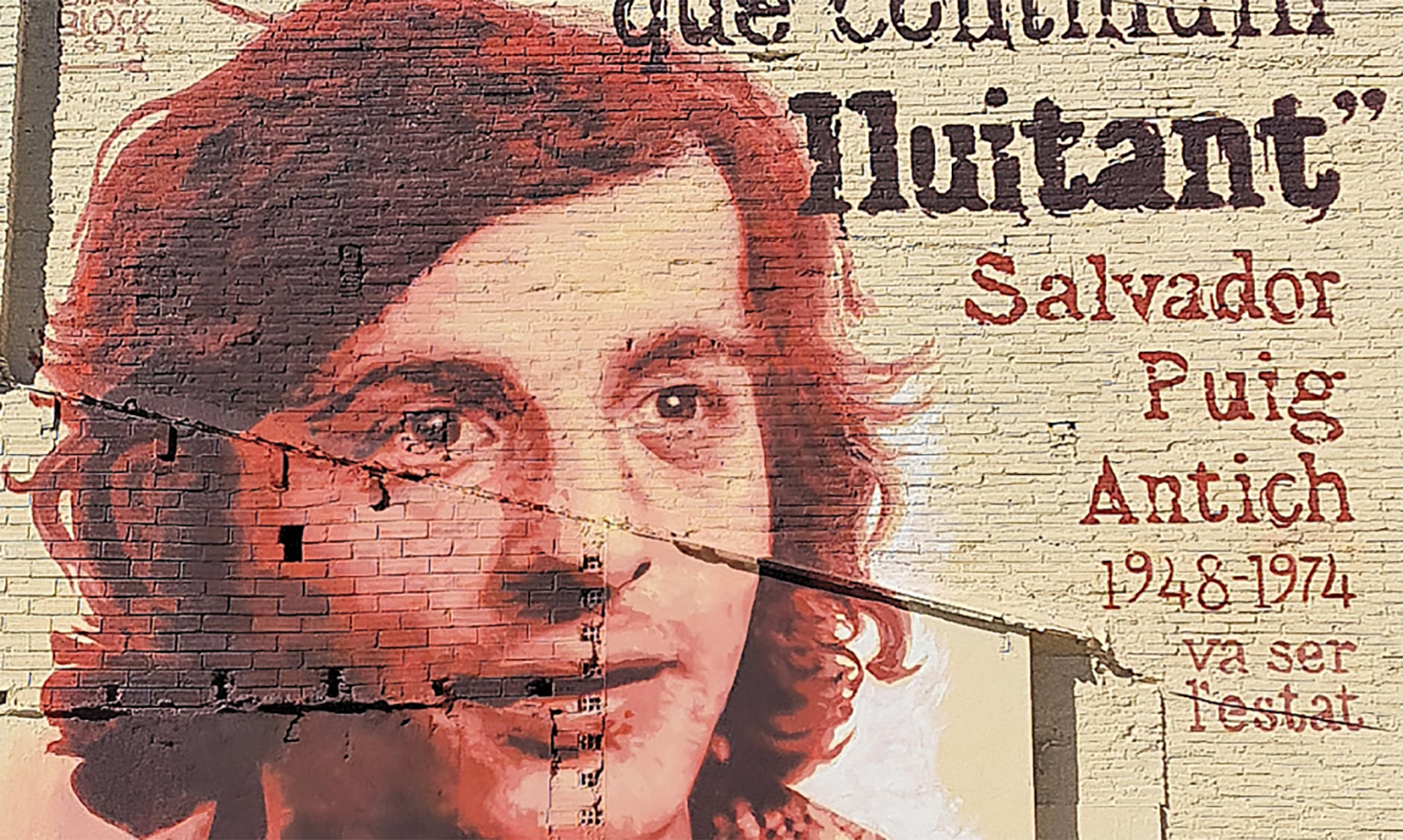

Mugalde yes, but we opened another one in San Juan de Luz. Axular. However, the political situation was not secure. In Portugal, the Krabelin revolution took place in 1974. In the Spanish State, the repression of Franco had not stopped, the last five strikes on September 27!, and we Basque Spanish Battalion put another device back on. We would not think it right away, but the attack was going to happen again. Franco died in November and the following year we returned provisionally to Pamplona, where the situation was inkili-manca. However, in 1977 we returned definitively, at the request of the PNV. There was a new era, the legalization of parties, the return of the historical exiles, the campaign for the constituent Courts in Spain, the implementation of our means…

“Hamar urte nituela kaputxinoen San Antonioko eskolaniara jo nuen. Latinez, gaztelaniaz eta euskaraz kantatzen zen. Aita Donostia, Isidro Ansorena, Jorge Riezu, Damaso Intza, Hilario Olazaran… ezagutu nituen. Komentuko sotoan egiten zuten Zeruko Argia aldizkaria”.

“Ikurrina jarri genuen Bi Haizpen Aberri Egunaren karietara. Egunean bertan, goizean goizago, guardia zibilaren telefono-deia gure etxera, nire anaiari laguntza eske, Goi-mendiko Eskolaren zuzendari baitzen. ‘Gipuzkoar’ batzuek jarritako ikurrina kentzen laguntzeko eskatu zioten. Anaiari esan nion guardia zibilari adierazteko aste santua zela eta eskalatzaileak mendian zebiltzala, material guztia hartuta. Ez genuela laguntzeko modurik. Lizarrako erregimentuko soldaduak saiatu ziren gure ikurrina kentzen, baina ez zuten lortu. Arratsaldean berandu, Candanchuko mendi eskolako soldaduek kendu zuten”.

“Donostiatik Iruñera nentorren, Roncalesako autobusean. Tolosan, Benta Haundi parean, ibilgailu ilara. Trafiko istripua ematen zuen, guardia zibilaren botak izara baten azpitik ageri, motorra lurrean… Autobusa gerarazi eta guardia zibil bat igo zen, metraileta eskuan, txoferrari galdezka ea Donostiatik gentozen denok. Baietz, txoferrak. Iruñera heldu eta zain nituen Artajo, Asurmendi eta Jaunarena, kezkatan, urduri. Haiek kontatu zidaten: Pardines hila, Etxebarrieta hila…”.

“1972ko azaroan hemeretzi eguneko gose-greban parte hartu zuen nire emazte Maria Luisak, hainbat errefuxiaturen deportazioaren kontra. Hura Baionako katedralean, ni inprimategian lanean, eta Aitziber alaba, txiki-txikia, Iruñean”

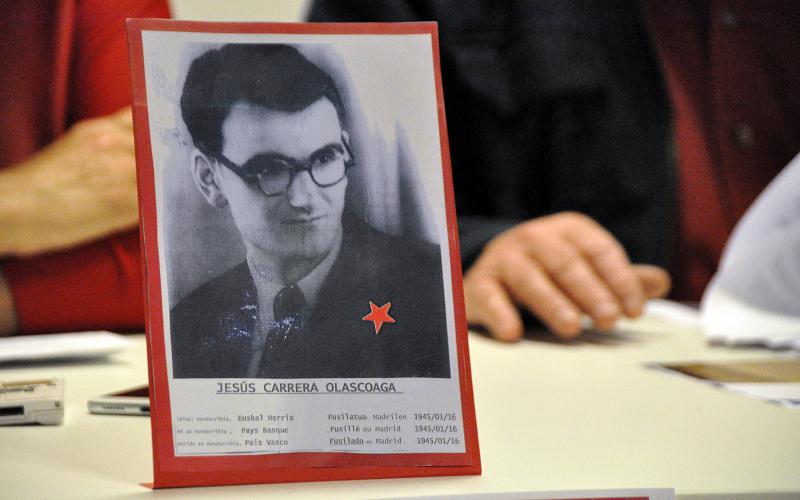

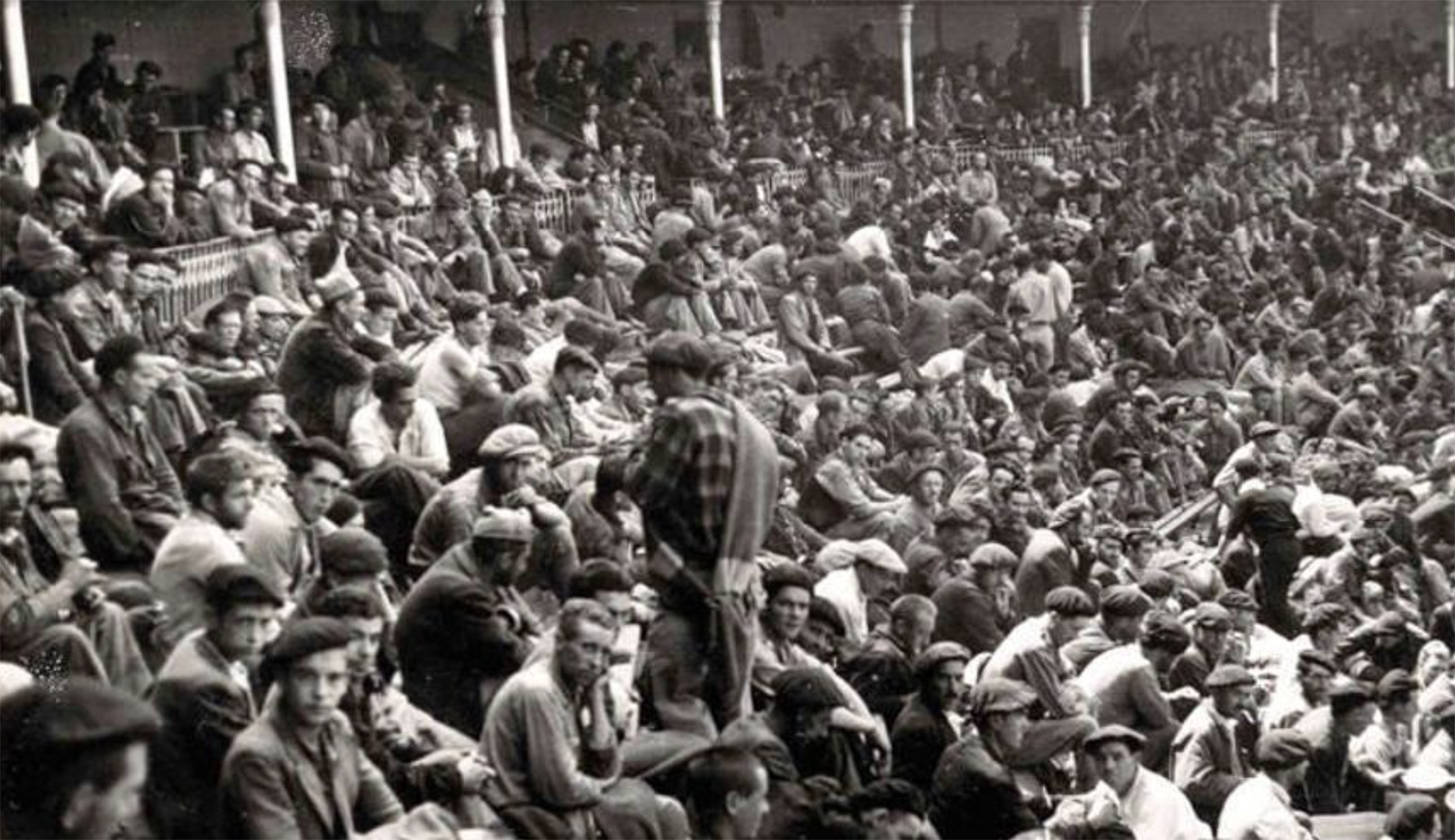

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

This text comes two years later, but the calamities of drunks are like this. A surprising surprise happened in San Fermín Txikito: I met Maite Ciganda Azcarate, an art restorer and friend of a friend. That night he told me that he had been arranging two figures that could be... [+]

The Dual sculpture, placed on Ijentea Street, was inaugurated on May 31, 2014 in tribute to the 400 Donostiarras executed by the Franco regime during the coup d'état of 36 and the subsequent war. It was an emotional act, simple, but full of meaning. There they were relatives and... [+]