"We need long-term strategies in popular movements so we don't always respond."

- Haizea Núñez was born in Euskal Herria, grew up in Madrid and returned to Donostia-San Sebastián at the age of 23. When he started studying Law, I already knew that it was the strategic weapon of power and not the field of blind justice that judges us all equally. However, he has served as a lawyer for the past five years and has offered legal protection to activists from various trade union movements and organisations.

Madrilen hazi zen Haizea Núñez, eta orain sei urte itzuli jaioterrira. Zuzenbide ikasketak egin zituen Madrilgo Unibertsitate Autonomoan eta EHUn, eta hainbat okupazio-mugimendutan buru-belarri ibilitakoa da. Beste hainbat kiderekin batera, Donostiako Okupazio Bulegoa sortu zuen. 2011tik hona, Atzieta kolektiboan jardun da abokatu. Irailean utzi zuen taldea, eta orain LABen ari da lanean.

When did he come to live in Euskal Herria?

2010. I was born here, but when I was little we went to Madrid, because my father got a job there. Her parents are Donostiarras, and her grandparents lived here. In July 2009 my grandfather died and my father is the only son, because in summer I came here to mourn with my grandmother. I had already decided that I had to leave Madrid, because there were very rapid dynamics both in popular movements and in university. Then, in addition, they brutally evicted some occupied buildings, murdered the young Carlos Palomino, arrested some of the nearby buildings violently… I decided to return to Donostia, because I always had this feeling that we were Basques, although somehow we were also Madrid.

The M15 movement was about to arrive. What atmosphere was there in the city?

In the previous years, public and massive sit-ins were held in favor of housing and in most of the neighborhoods of Madrid a lot of busy social centers and culture of self-management were opened.

You studied law. What view did you have of the right before you started your studies?

When I finished high school, my intention was to study philosophy or history, but my parents told me that that didn't work at all. There was a dual bachelor's degree, political science and law. In the second year I decided to abandon the political sciences and continue with the law, on the one hand because I wanted to finish the studies, and on the other because I saw that the training in it could be useful, above all, from the point of view of popular movements.

But I knew it was a strategic weapon of power. I knew it was the enemy's tool to crush us.

And after completing the studies and being a lawyer, what do you think about the law?

Now I know that we also have tools to change law, and that to the extent that law does us, we can influence it. On the other hand, I now know that what we learn in class does not happen in the courts afterwards. However, it is true that in law theory we were once quoted as a current within law: the so-called sociology of law. According to that, it is much more important to know what the judge thinks about this or that matter than to know the laws themselves. That is the case. You should know which magistrate is in front of you.

What other difference is there between studies and activity?

In class, we learn that the law is positive, objective, that if you follow the jurisprudence you will get the result whatever it is, and that doesn't happen. This is how we prepare things, but we have to take into account other strategies: if it is the case of popular movements, how this case is dealt with in a communicative way, what pressure it can put on the judge and on the contrary. There are other negotiation strategies and they never explain to you, they don't tell you what instruments prosecutors have in criminal matters. Until you go out, you don't know what a judgment is.

You mentioned popular movements on more than one occasion. What and how did you start?

When I was in college, the movement against the Bologna Plan was wobbling. In Madrid there was a coordinator of student assemblies, and we made a law assembly and from there I entered the occupation and housing movement.

We occupy a building at Complutense University and we call it Self-Managed Okupada Faculty. It lasted three months. The rector of IU, Carlos Berzosa, sent us: The hundred and the police officers were there that night to say goodbye to the 10 people we were watching the site. That's how I started.

What before college?

I was in a very privileged school, in La Moraleja. The parents wanted to pay our education well and sent us where the children of the PSOE elite and the bourgeoisie progresses from Madrid study. I was always in that school, in a little ghetto, until I went to public university. Until then, I only saw political issues on television, in books, or in family debates, because my father has always been left-wing and Euskaldun, while my mother comes from a right-wing family.

So you took a deadly leap.

Yes, and it was very strong. On the one hand, I decided to go to public college, and not only that, but I started working in a nursery near home, taking care of the flowers, so that first year, I was almost not at my parents' house. Then, in the second year we occupied a block and a kind of explosion occurred: I left home and, in addition, I left the closet.

What did the occupation give him?

At first I saw it in a very idealistic way. In this project, we put together very different people: on the one hand, those of us who came from the student movement, and on the other, people for housing, people who lived on the street and others. Some of us were very privileged, every day we went to class or to work, and others, on the contrary, had other needs. In addition, it was very important for us to go to the assemblies and all that, then there were great clashes, we received a huge hit.

Without that experience, I wouldn't be what I am today. There we lived some women and it was very important to train ourselves in different aspects, even in the shock, to discuss with the children who were part of us about the decisions. Every day we struggled and created things. We spent a year in that block, and then we occupied a home in another block just women.

Why?

It was about evicting the social center La Alarm, and there was resistance. After several micro-machismos and aggressions, we held an assembly and proposed to meet only women. We set up a feminist group, and some of us had concerns about jail. We went to Galicia to a few days about women and prison and decided to make a special group of visits to social prisoners. Then we occupied the house so that we could live ourselves and so that the prisoners could come when they had permits.

Speaking of the Moorish Law: “Those in power have learned that we respond to this collectively and that it’s not as profitable to have people like us in jail.”

What was the experience of the visits?

Our project was to get in touch with a lot of women, and in the end we contacted a single woman who told us she needed visits. On the other hand, we had macro-prisons, Soto del Real, etc. But we went to Brieva to a very small jail. We saw that the people of Euskal Herria were going a lot to the jails, and the Gypsies were going a lot too. In addition to these two clans, the prisoners were fairly abandoned. As long as there's no community, people stay very lonely in jail. Finally, our intention was to build such a horizontal relationship, but it was difficult, because the one inside has special needs and knows that the one outside has more resources for the mere fact of being outside.

How long were you talking about that?

We occupied the house in November 2008 and were kicked out in March 2010. Then I was at my friends' house and then I came here. As for the visits, I did not, but the colleagues continued with the project.

How did Euskal Herria welcome you?

It was very difficult. I came in May 2010, and in July, I had a traumatic event. After the Patti Smith concert we went to six people at Be Bop bar: five girls and one boy. One of the friends went to the toilet and a man followed him and attacked him. The colleague managed to zafate from him, but the man followed him again, grabbed him and we helped. The guy took a glass and threw it in my face. Imagine, newcomer, with my face broken... at one point I broke myself inside. Fortunately, I was cared for by a friend and I was also helped by members of Bilgune Feminist and the Medeak group.

The Basque Country, at least, has not been an obstacle.

It was very clear that I was coming to look for the Basque country, which didn't want to kill my grandmother without talking to me in the Basque country.

I recently said something very concrete, but it is true: the Basque Country has given me freedom, and peace of mind. The injury of our people goes right through our family: on the one hand, the mother's family has trampled the language; on the other, the Basque language is a language that comes from the father's family. In a way, I felt a historical responsibility. Some have tried, unsuccessfully, to cut this branch and I come to prevent it. After all, if my father had been a German, he would know the language from a young age.

You mentioned Euskera and freedom. What is the situation of the Basque Country in the courts?

There are major obstacles. Most officials do not know Euskera and it has happened to us that the judge tells us that the translator has not come and that then we will do it in Spanish, “if you don’t care”. These violations occur on an ongoing basis.

We live in a very sad paradox. For example, if a woman comes to us who has suffered machista violence and wants her process to be done in Basque, the lawyers have to tell her that the procedure is going to take a long time, because there is a translation, and therefore, if we want things to be done quickly, to get the order of removal as quickly as possible, and all that, then, we have to do the procedure in Spanish. On the contrary, if we are going to defend ourselves, we introduce all the writings in Euskera, we write potolos, to get time and, in the meantime, to extend an occupation.

Recently, among other things, he has been a lawyer for the Gipuzkoa Zutik movement.

There are currently four cases in the courts. Several administrative files have been opened against those who participated in Gipuzkoa COY, in application of the Moorish Law, but in the three arrests only the Ertzaines have their claims, and the judges believe that there are sufficient indications to think that there were illegal arrests, that the Ertzaines used the law very maliciously to remove it from the street. Then there's another case, an attack on a journalist.

Normally, the lawyers we're in these cases are always in defense, but this time we've moved on to the offensive, because we've seen that they've used all the instruments they had to silence them and get people out of the street. I am clear that they arrested people for fear, because most of the people there had not participated until then in the street protests and did not know how to deal with a detention. They wanted to put an end to this force, despite peaceful actions. We wanted to show that in that game too we will set our limits.

What are the risks of the Mordaza Law and “soft” repression?

I believe that those in power have learned to respond to this collectively and that it is not as profitable to have people like us in jail. On the contrary, economic waste and damage do them well, and having people don't know how much time organizing the questors, because at that time we're not thinking or building.

And in the face of that, what do you do?

Acting on different fronts. We need to anticipate very well what action we want to take, perhaps also to make budgets. On the other hand, we must guarantee the sovereignty of life in different areas. We need a comprehensive strategy. I believe that it takes time to have some debates, but our agenda always goes quickly, always in the answer: they catch us there, because we have no long-term plans. It seems to me that in popular movements there is no such strategic vision.

Are you, however, hopeful?

For example, there is a nice bet on the transformative social economy. We are building things, but not so much in confrontation. But well, confrontation and construction always have to act in a sort of waltz.

Gogoan dauzkan kasuez galdetu diot Núñezi eta irribarrea ezpainetan ekarri du bat gogora: “Oso kasu polita izan zen Urkulluri Kursaalean egin zioten eskratxearena. Hiru ekintzaile sartu ziren, pankartekin eta beste, kantuan. Oso polita izan zen

zeren epaileak benetan sinesten zuen Urkulluk halako errieta bat merezi zuela”.

Pasa den asteko "kaleratze ilegala" salatu dute hainbat herritarrek, ostiral arratsaldean.

Joan den asteko kaleratze "ilegala" salatzeko, manifestaziora deitu dute ostiral arratsalderako.

Ustez, lokalaren jabetza eskuratu dutenek bidali dituzte sarrailagileak sarraila aldatzera; Ertzaintzak babestuta aritu dira hori egiten. Birundak epaiketa bat irabazi du duela gutxi.

Protestak 24 ordu bete dituenean, suhiltzaileak bertaratu dira udaletxera eta kateak moztu dizkiete bi gazteei. Bi kateatuek gaua bertan igarotzea "udaletxearen hautua" izan dela adierazi du Gazte Asanbladak, eta udalaren ordezkariek "ekintza deslegitimatzeko eta bi... [+]

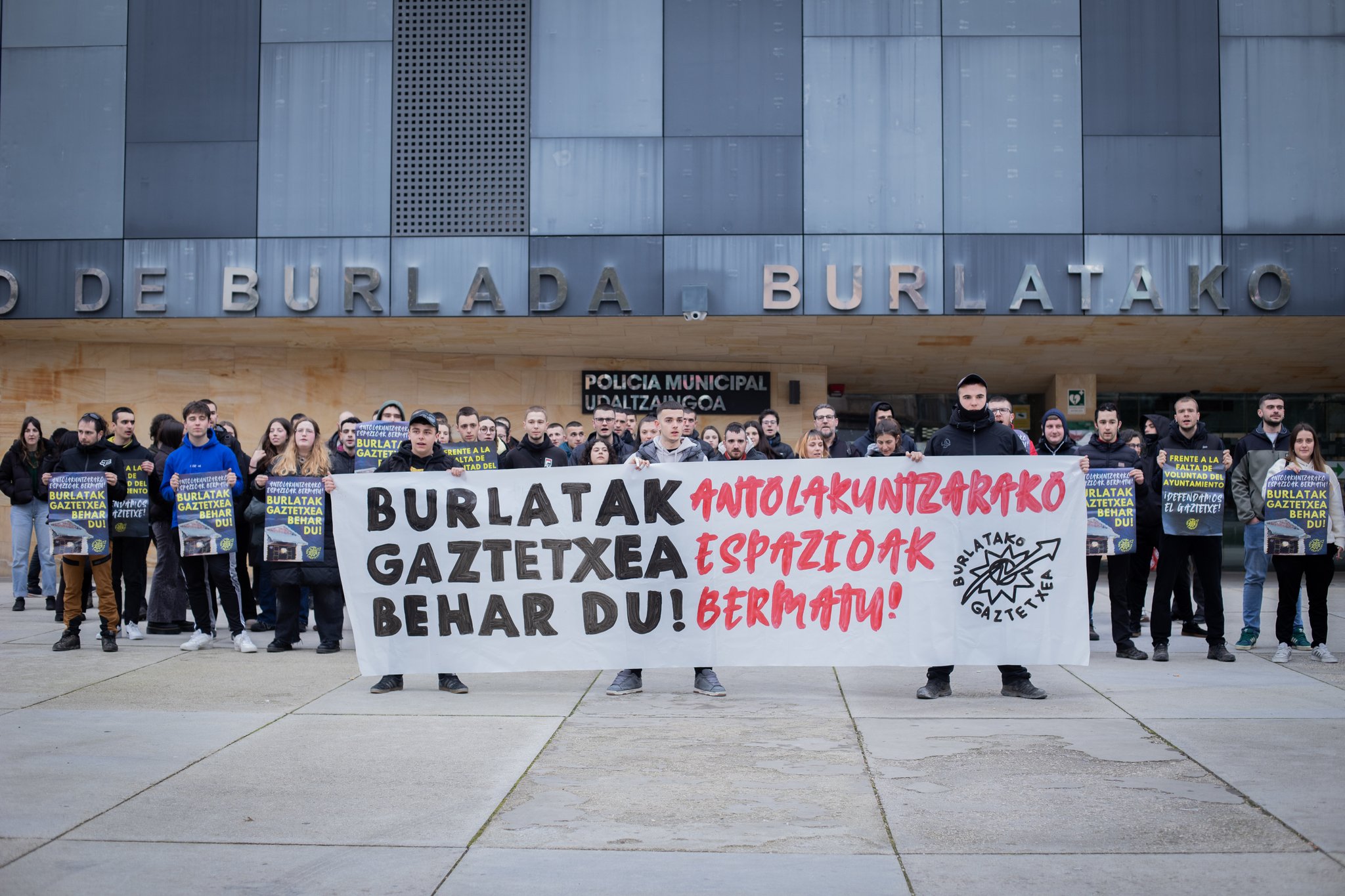

EH Bildu agintean dagoen udalak gaztetxearen etorkizuna ziurtatzeko aterabide bat adosteari "uko" egin diola salatu du Burlatako Gazte Asanbladak. Beste hainbat gaztek udaletxe kanpoan kanpatu dute, eta goizean zehar bertara hurbiltzeko dei egin dute.

Iruñerrian bat egin dute hainbat Gazte Asanbladak, Burlatako Gaztetxearen alde. Etxarriren desalojoa gelditzera deitzeko, bestalde, manifestazio bat antolatu dute Bilbon hilaren 28rako.

Asteburu honetan hasiko da Gaztetxeak Bertsotan egitasmo berria, Itsasun, eta zazpi kanporaketa izango ditu Euskal Herriko ondorengo hauetan: Hernanin, Mutrikun, Altsasun, Bilboko 7katun eta Gasteizen. Iragartzeko dago oraindik finala. Sariketa berezia izango da: 24 gaztez... [+]

Festa egiteko musika eta kontzertu eskaintza ez ezik, erakusketak, hitzaldiak, zine eta antzerki ikuskizunak eta zientoka ekintza kultural antolatu dituzte eragile ugarik Martxoaren 8aren bueltarako. Artikulu honetan, bilduma moduan, zokorrak gisa miatuko ditugu Euskal Herriko... [+]