A little space for more writers

- You're a young, literary enthusiast, you write something, but there are very few people around you who give you a critical view of your work. He has tried in calls for scholarships and prizes without great results. You're a young man, a fan of literature, you'd like to keep writing, but you keep less and less text in the drawer.

Ten Basque authors under 30 years of age have published a literature book for adults: Alaine Agirre, Itxaso Araque, Amaiur B. The documentary is attended by Blasco, Hedoi Etxarte, Gari Irazusta, Anartz Izagirre, Gorka Salces, Danele Sarriugarte, Garazi Ugalde and Samara Velte (Kattalin Miner, coming soon). Except for Agirre, Blasco, Etxarte, Irazusta and Velte, the remaining five have left for the plaza with a scholarship or prize, while Irazusta’s is self-edited. On the other hand, there are

20 years of difference between the last two literary bands that have been here – in 1993 the Lubaki Band manifested, in 2013 they launched the iepa-kaixoa of the ITU Band. 20 years, with its autumn leaves, 7,306 days, with its melancholic sunsets, among the last two groups of young people who have met continuously to make literature – you may save those of Vladimir magazine or the late Kevin Heredia. What links these two data together, someone might think, why the spiral was robbing, it begs in unsolid connections, suggesting a possible crisis, when and now, at a time when Basque literature advances healthier than in Marino Jaizkibel.

But suppose that behind this data there is an interesting topic, that there are reasons to dispel, and that, like that investigative expert, we turn him around the question: why a young day returns home exhausted from his work, devours a frightening salad, gives a cup of coffee, puts himself in front of the computer and writes, for example, a robust novel (except for a therapeutic supernatural function). ), Ramón Saizarbitoria says – and Ustela, Oh! Many of the young people who have worked in literary journals in Euzkadi and at the time have felt this in a similar way: in the beginning, writing without having a group around them would not have made sense. Apparently, they were encouraged to keep writing when they realized that among them, something was being done for the people. What about the solitary souls of two decades between the canosa of Luyemen and the smooth skins of UTI? Why will the buttocks be glued to the bank for many hours, fully handed over to the literature? For Basque culture? To put your bit of sand into the national construction?

Excuses from IKEA, someone will say quite rightly. But whoever wants to write will find time and way to do it yesterday, today or St. Fermín's day. But the question we want to raise here is another: if in this panorama the current conditions are the most suitable for a young man who wants to test the literature, or, in other words, if the conditions were different, there would be no stronger literary movement among the young. Or to put it in a third way: if there is a will to collectivize a little the leap to youth literature, to overcome the current model of scholarships and prizes that admit a single winner (and many losers) and start to devise other formulas.

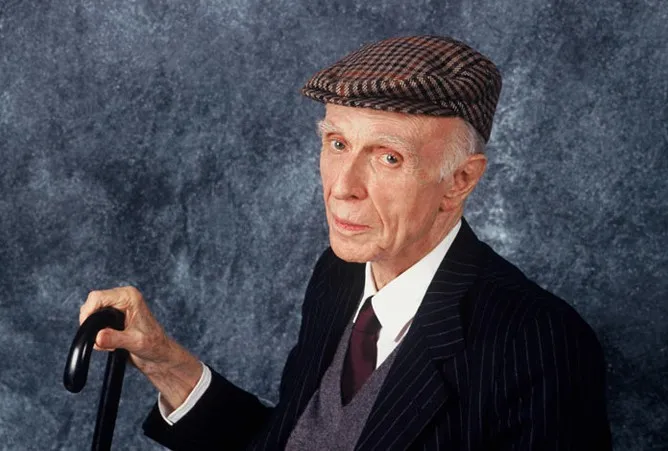

EKAITZ Goienetxea

“Literary contests look like this: they are discriminatory. For me, the cruelest thing was not to receive a single mention. I didn’t even know if that text had any literary value.”

Lack of feedback

Let us return to the words of Saizarbitoria: “(The Prize Prize) is a very serious issue, because every time someone awards they leave others unrewarded.” Although Pello's truth may seem, the phrase is based on it, there is nothing to say if those who participate in these awards are young newborns. Itziar Ugarte of the ITU band recently noted: “To many young people, the only way we have left to publish is to present ourselves to competitions and, through them, to make the leap to publishers. This system, besides generating competitiveness, means leaving many texts in the drawer. That’s why we’ve created Lekore, because we needed a space to freely publish texts from young people.” That is, in essence, Lekore magazine: an attempt to deal with the existing rules of play.

Scholarships and prizes are double-edged swords, for whom he has a preaching to writing but has never published anything: in case of winning, in addition to publishing his first work, they are a stimulus to keep writing. However, it may happen that a young man who presents himself to the calls and receives no prize is definitively discouraged from any literary intention. No, surely, because he was blinded by the awards or the publication, not because he was represented on the cultural pages of the newspaper, with the premium opera under his arm and the pompous headlines. You will depart from the literature, above all, because you have not found anyone – other than close friends – to give you feedback on your work, someone to explain to you if you have done something serious, bad or mediocre, and because, failing that, the scholarships and prizes you have not won could play that role – and, of course, as the lack of response is usually understood because you have understood the lack of response.

Ekaitz Goienetxea, recently awarded the Igartza Prize, missed that feedback. Two years ago, two works were presented to the Gabriel Aresti story contest and both were awarded. “The oldest of the stories, despite being presented to other competitions, never received the slightest mention. Until then, it had been invisible. Because literary competitions also look like this: they are discriminatory. For me, the cruelest thing was not to receive a single mention. I didn't even know if that text had any literary value. At least it would be OK to receive a short text comment from the jury, if they have seen something to improve, what they liked and what not, if they have any recommendation.” In this void, it occurs that, apart from literary contests, a network of critical readers is created so that any novel writer, or not as a beginner, can submit their works. By the way, Goienetxea adds: “There are five years of difference between the two stories he sent to the Gabriel Aresti competition: after writing the oldest one, it took me five years to write a new story.”

Mikel Peritua:

“I think it’s a small reward and annoying tool.”

Write for money

Here and now there are those who write Basque literature for money. Paradoxically, but another consequence of the model of scholarships and prizes is that, although in theory they have been created to help literature lovers in their hobby, it can happen that, by the candy of the prize, there have been won people who would never write if it were not for the candy of the prize. For the winner, the election is entirely legitimate, but does not seem to coincide with the goal of the prize. In other words, if we talk about giving a boost to young people who want to write literature, the current formula of prizes and scholarships may not be the most effective.

Goienetxea, passionate about literature, has written for money. Gabriel Aresti took the job of preparing the second story of the competition, as he was unemployed and was looking for income: “As a writer, I saw an opportunity that wouldn’t harm me trying. Those of us who have become accustomed to working here and there are attentive to calls for scholarships, contests or aids. It’s also a way to get ‘employment’. Each in its respective area. And because I have writing experience and a little bit of creativity, I dared to introduce myself to literary calls.”

At the awards, the jury assesses at least the literary text. In scholarships, on the contrary, extralitarian reasons can have an important weight, such as the skill with which you sell the project. This is how Goienetxea lived: “Submit a project, defend that you will be able to develop that project, argue that you must seduce the jury knowing that... And if you're chosen, then you have to start working. In the two scholarships given to me this year, I have been questioned whether it has not been because I have developed the ability to argue a project well over the years of experience in the field of advertising.”

Ramón Saizarbitoria:

“I’m sure that with the amount of money they spend on literary awards and on less necessary things, a dozen writers, without more work, would have enough to live in their production”

Profit-sharing

Moreover, it is not easy to propose in detail useful formulae, but the direction they should take is quite clear. In general, the issues that have been mentioned on many occasions about prizes have the same importance for scholarships and awards for young people. These are voices that have defended a more collective distribution of benefits compared to the competition and formulas of exaltation of a few writers. An in-depth idea unites these proposals: today, here, most artists have no choice but to create in a precarious way until they win a contest or a call for scholarships, and that has to be turned over, so that whoever wants to create something can participate in the process in the most dignified conditions possible, as is the case of the theatre, which is increasingly the companies that defend this formula. It is not yesterday's cry at noon. Saizarbitoria’s comments on the Association of Basque Writers date back to 2001: “I’m sure that with the amount of money they spend on literary awards and on less necessary things, a dozen writers, without more work, would have enough to live in their production.” Then he added: “This would be a topic to take seriously, but it’s that writers are the way we are and we’re not going to take it seriously.”

Similar echoes could be seen in the text published a year ago by Mikel Peruarena in his blog to explain the renunciation of the Euskadi Prize for Literature. This – being the context – put the public administration in the spotlight. He felt that literary production, creativity and other means of promotion of the authors were taken from his struggle: “It seems to me a small prize instrument and it bothers me.” In addition, he argued that literary competitions can be done differently, and that, for example, instead of awarding a single prize, it would be more appropriate to highlight a dozen or a half of books published a year “making an essential criticism of these books”. Other instruments to promote creativity with public money, such as the creation of special tax statutes for creators or the creation of tax incentives, were cited in the same text: “Let’s suppose the authors who are going to publish the book this year are given back a little while making the tax return. Or create special aid for the unemployed.” There is currently no fully public literary scholarship for young people.

Ainhoa Larrañaga has been on the jury of the Euskadi Literature Awards in recent years. It also mentions the need to go beyond the formula of scholarships and prizes to promote cultural creation. But he sees a big impediment to this. “We do not have a state and therefore a strong instrument for protecting culture. We have literary awards or other similar initiatives, but as a subaltern administration we only get to that.” It can therefore be thought that the implementation of these measures is not as easy as it seems, that we have our hands tied, because we are under the rule of two states. In this scenario, we could try to use the competences we have at least to promote more democratic initiatives of cultural creation, or, if not, continue to do so and move this issue to the waiting room for the things that will change with the achievement of a state of its own. The day after independence, great new developments are expected in this people.

Odolaren matxinadak. Gorputza, politika eta afektuak

Miren Guilló

EHU, 2024

Miren Guilló antropologoaren saiakera berria argitaratu du EHUk. Odolaren matxinada da izenburu... [+]

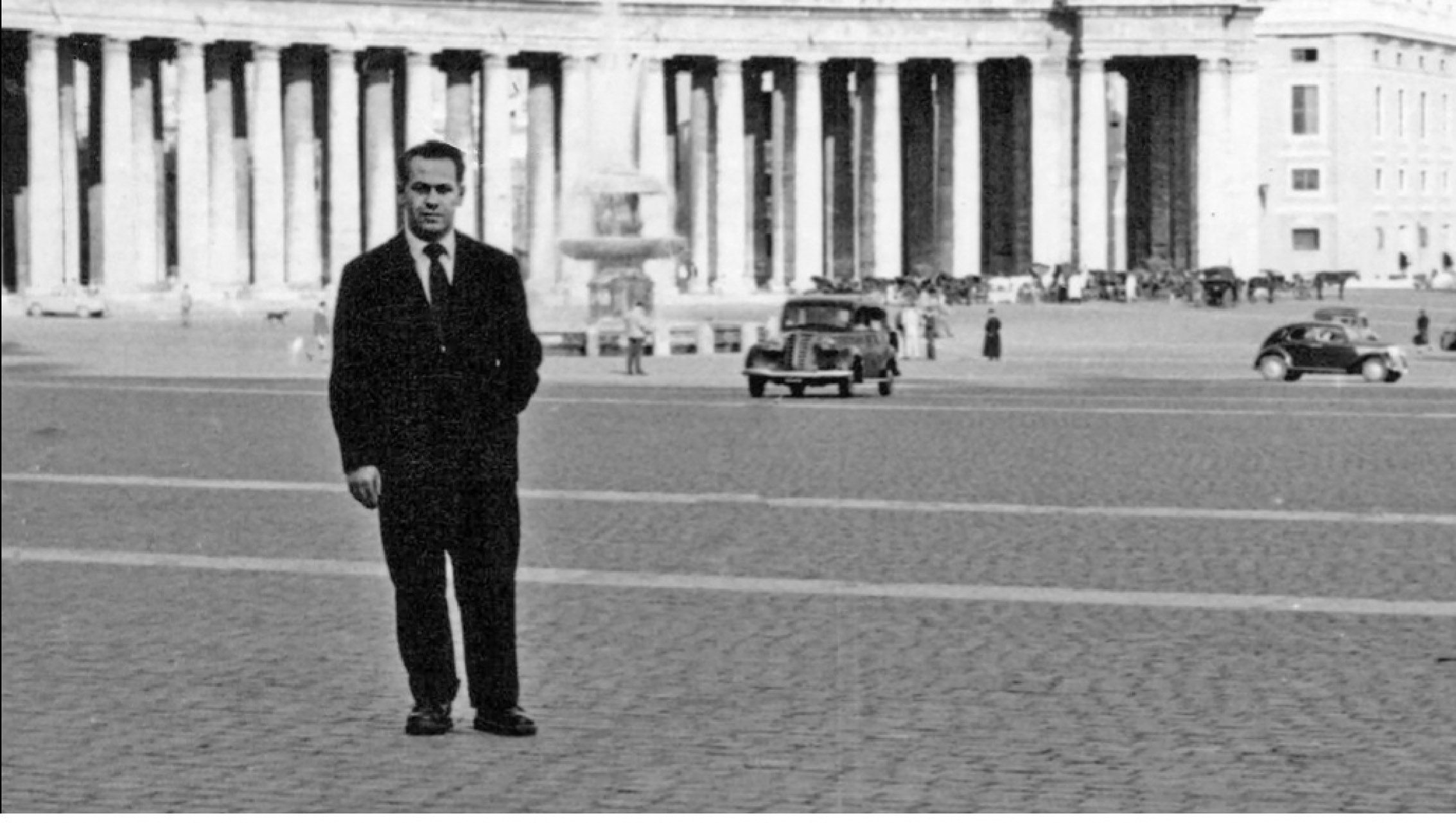

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Zero. Transhumanismoa ate-joka erdi aro berrian

Aitor Zuberogoitia

Jakin, 2024

-----------------------------------------------------------

Hasieran saiakera filosofiko-soziologikoa espero nuen, baina ez da hori liburu honetan aurkitu dudan bakarra. Izan ere, biografia... [+]

Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999) idazle argentinarrak 1940an idatzitako La invención de Morel (Morelen asmakizuna) eleberria mugarritzat jotzen da gaztelaniaz idatzitako literatura fantastikoaren esparruan. Nobela motza bezain sakona da, aparta bere bakantasunean, batez... [+]

Anton Txekhov, Raymond Carver eta Alice Munroren ipuingintzari buruzko mahai-ingurua egin dute Iker Sancho, Harkaitz Cano eta Isabel Etxeberria idazle eta itzultzaileek, Ignacio Aldecoa zenaren ipuin literarioaren jaialdian, Gasteizen. Beñat Sarasolak gidatuta, autore... [+]

Ihes plana

Agustín Ferrer Casas

Itzulpena: Miel A. Elustondo

Harriet, 2024

---------------------------------------------------------

1936ko azaroaren 16an Kondor legioko hegazkinek Madrilgo zenbait museori egin zieten eraso. Eta horixe bera da liburu honetara... [+]

Joan den urte hondarrean atera da L'affaire Ange Soleil, le dépeceur d'Aubervilliers (Ange Soleil afera, Aubervilliers-ko puskatzailea) eleberria, Christelle Lozère-k idatzia. Lozère da artearen historiako irakasle bakarra Antilletako... [+]

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

Etxe bat norberarena

Yolanda Arrieta

Alberdania, 2024

Gogotsu heldu diot irakurketari. Yolanda Arrietaren obra aski ezaguna zait eta iragan maiatzean argitaratu zuen proposamen honetan murgiltzeko tartea izan dut,... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]

SCk Zerocalcareri egindako galdera sorta eta honen erantzunak, jarraian.

Euskal Herriko literatura gaztearen eta idazle hauen topagune bilakatu nahi den proiektu berriaren inguruan hitz egingo dugu gaur.

Rosvita. Teatro-lanak

Enara San Juan Manso

UEU / EHU, 2024

Enara San Juanek UEUrekin latinetik euskarara ekarri ditu X. mendeko moja alemana zen Rosvitaren teatro-lanak. Gandersheimeko abadian bizi zen idazlea zen... [+]