Homelessness in Sao Paulo: occupation

- The San Sebastian Film Festival hosted the film Era or Hotel Cambridge (Hotel Cambridge), about an abandoned 20-storey hotel that was occupied by 700 homeless people. More than 4,000 families live in squatted houses in Sao Paulo and is one of the strongest fighting camps of popular movements.

“It’s a great fortune to present this film between documentary and fiction at the San Sebastian Film Festival, but it’s more lucky to have this woman next to me: Carmen Silva Ferreira. If you don’t know who it is, it’s one of the true leaders of the housing struggle in Brazil, highly respected,” the director says by presenting his main protagonist.

“The film you will see is a reflection of the reality of Brazil, thousands of people live in the street, the fabels grow on the outskirts of cities, and at the same time there are thousands of empty houses and buildings abandoned in the center of the city – Silva speaks with sweetness and firmness. However, it is a very unfair system, since in Sao Paulo, for example, the government protects these houses, leaving people who enter them in the street in the name of the law. The state is a slave to those owners who leave these homes and owe the State a fiscal fortune; it makes no sense.”

.jpg)

Although since the 1980s movements in favor of the right to housing have worked in the street, given the seriousness of the problem, the movement was unified and one night in 2003, 2,800 people occupied four buildings in central São Paulo hitting the table. In the empty apartments and rooms that had been uninhabited for over 20 years, they massively organized their homes. In Sao Paulo the movements taking place in this area focused on giving visibility through direct action to homeless workers and citizens on the verge of social exclusion. In the center of the city they began to occupy the buildings demanding an emergency housing plan. The movement was formalized in 2004 as a focal point for various agents and was called FLM: Front of Luta by Moradia (Front of Struggle for Housing) They have a lot of information on their web. Today there are more movements working in this area.

Organising homeless citizens

In the film Era or Hotel Cambridge the assembly has been documented, which has ended with cries of “Quem não luta es es morto”. The residents of the entire building have gathered on the first floor to hear what Carmen Silva has to say.

“Today we celebrate the feast of occupation. We will all participate, and those who are new to us have to come. It will last 48 hours and the friends of the other three blocks are also on their way.” In the evening you can see several buses running at high speed in Sao Paulo. They have stood in front of an abandoned building in the centre, the door sealed with a shovel has been broken quickly and in a few minutes hundreds of people have entered. The tension that these images convey is such that the viewer can be breathless. Silva gives encouragement as “Go in, fast, it’s your house!” to all Paulists of all ages running from buses one to one and living homeless in the largest American metropolis. Once they all entered the abandoned building, the buses left, closed the door from one side to the other and within minutes came the military police officers, who ordered them to leave the loudspeakers. The hundreds of people inside the house will say no. The FLM flags will be hanging on the windows. Another occupied building. Another open front.

According to the BBC in a report entitled Life in Sao Paulo, in March 2015, hotels occupied by homeless people, according to the Military Police, from early 2013 to late 2014, 681 buildings or land were occupied. In 2015, some 4,000 families lived in central São Paulo in buildings occupied and coordinated by popular movements.

Urbanist Jeroen Stevens of the Federal University of Leuven (Belgium), who analyzes this political phenomenon, explains how it works as follows: “They have a common agenda for occupations. Many work to raise awareness about the duties and rights of people they did not have in society.”

These movements have chosen to live in the center of the city and, therefore, have broadened the debate about their participation in the public scenario, according to the sociologist Janaina Aliano Bloch in his arduous struggle for housing in the center of São Paulo. “Their demands are not only contrary to the segregation of space, but are also contrary to social and political exclusion. These popular movements, which are left out of the political debate, claim their place,” says Janaína A. Bloch.

The miner Jehovah, who lives with 23 other families, has been interviewed today on the BBC. He says that until then he saw the occupations as “barabbas thing”, until he had to go to live one of them. It is the destination of thousands of poor citizens who cannot afford to pay the rent with a minimum wage: To sleep in the street, to go to live in misery to a fabel just outside the city or to occupy a house.

In May 2007, Amnesty International visited another occupied building in central Sao Paulo. This was managed by the MSTC movement, which is part of the FLM, and the representation was composed almost exclusively of women. AI explained that almost all families joining the movement were in the hands of a woman, most of them close to social exclusion. Ai put on the table that the women of the MSTC came very well to be part of a movement and that for the first time many have experience in political activism and leadership. After a powerful campaign that managed to overcome the borders of Brazil, the City Hall served to convince all the residents of the housing building in the city.

The earth, happy with gold and speculators

One of the MTST leaders, Ghilherme Boulos, has been interviewed in the Ctxt area in December 2015. In his words, "the struggle of the homeless has increased greatly due to the urban crisis that deepened before the economic crisis. Loans granted to real estate companies in 2004 amounted to 5 billion reais and in 2014 amounted to 102,000 million reais, an increase of 2,000%. In addition, the price of housing in Sao Paulo has risen by 212% in eight years, 260% in Rio de Janeiro. This means the expulsion of people. In the city gentrification is very powerful, and the World Cup and the Olympic Games have been accelerated. People are moving to areas that are far from downtown, and although 3 million public homes have been built, prices are still rising. It’s a machine to create homeless Brazil.”

In Brazil, land became gold in its own words, and renting, on the other hand, was something impossible to pay. The occupations have not only been produced in São Paulo, but the practice is also spreading in other cities of the country. “I think it is a phenomenon directly related to the explosion of housing speculation,” says Boulos.

After returning to the Cambridge Hotel on 16 September 2014, 250 military police finally managed to evict the building, leaving 700 people who had resided for six months in the street. In the city there were strong clashes between the displaced to defend the housing and the military police. Newspapers picked up on chronicles that some protesters and police launched rubber bullets, tear gas and sound grenades as they set off a bus in the city centre.

At the San Sebastian Film Festival, Carmen Silva, one of the activists and protagonists, has been applauded by the attendees after the film. They don't want anything for free. They want to pay their house at a fair price.

“Even though the media silenced it, the problem here is capitalism. The place changes the shape of the place and in Brazil it is very savage,” Silva said. They will continue to press with the projection of the documentary at the global level and also organize the evicted in the street. They claim this through the implementation of the right to housing. As they say, the non-combatant is dead.

Pasa den asteko "kaleratze ilegala" salatu dute hainbat herritarrek, ostiral arratsaldean.

Joan den asteko kaleratze "ilegala" salatzeko, manifestaziora deitu dute ostiral arratsalderako.

Ustez, lokalaren jabetza eskuratu dutenek bidali dituzte sarrailagileak sarraila aldatzera; Ertzaintzak babestuta aritu dira hori egiten. Birundak epaiketa bat irabazi du duela gutxi.

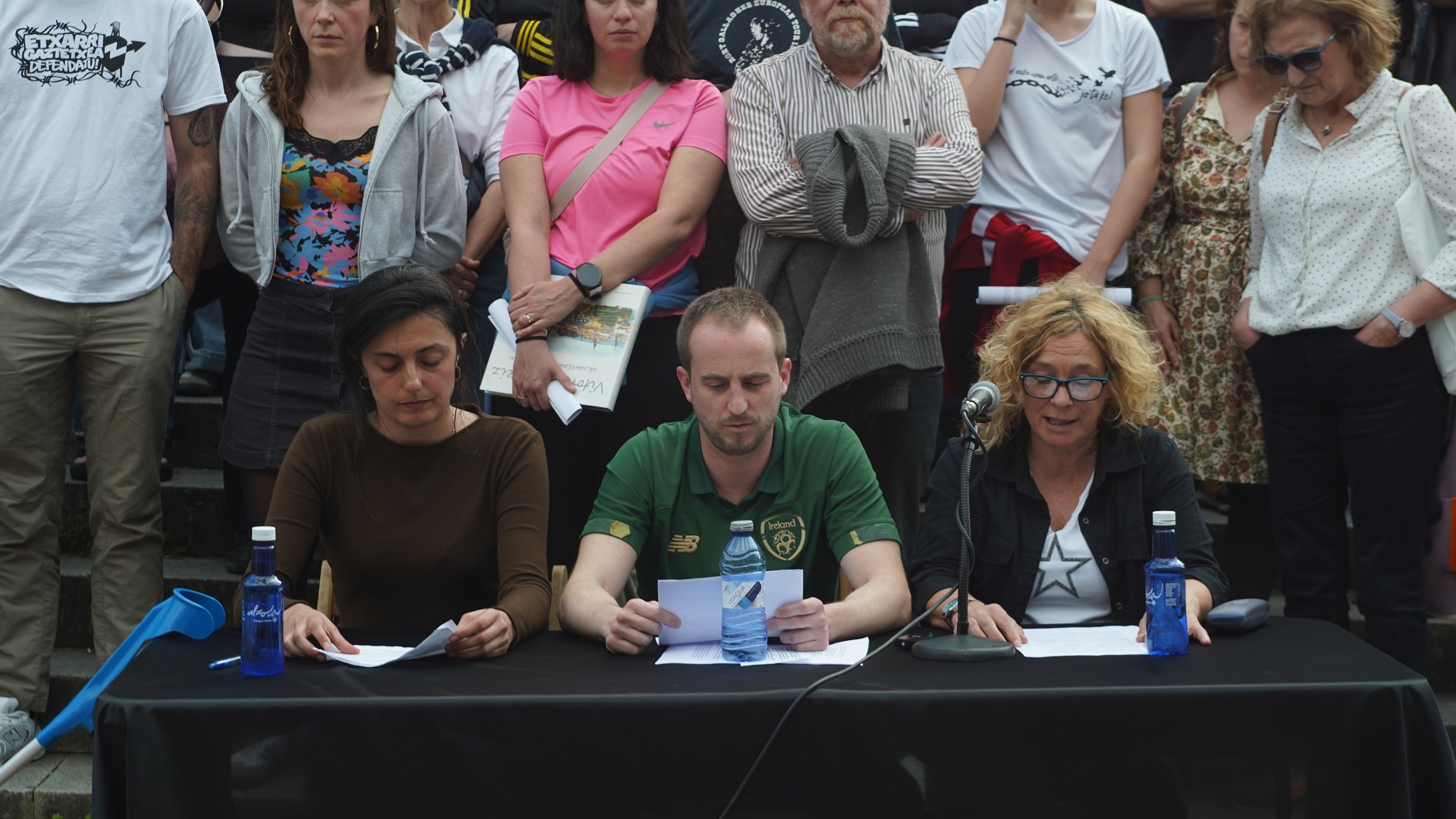

Protestak 24 ordu bete dituenean, suhiltzaileak bertaratu dira udaletxera eta kateak moztu dizkiete bi gazteei. Bi kateatuek gaua bertan igarotzea "udaletxearen hautua" izan dela adierazi du Gazte Asanbladak, eta udalaren ordezkariek "ekintza deslegitimatzeko eta bi... [+]

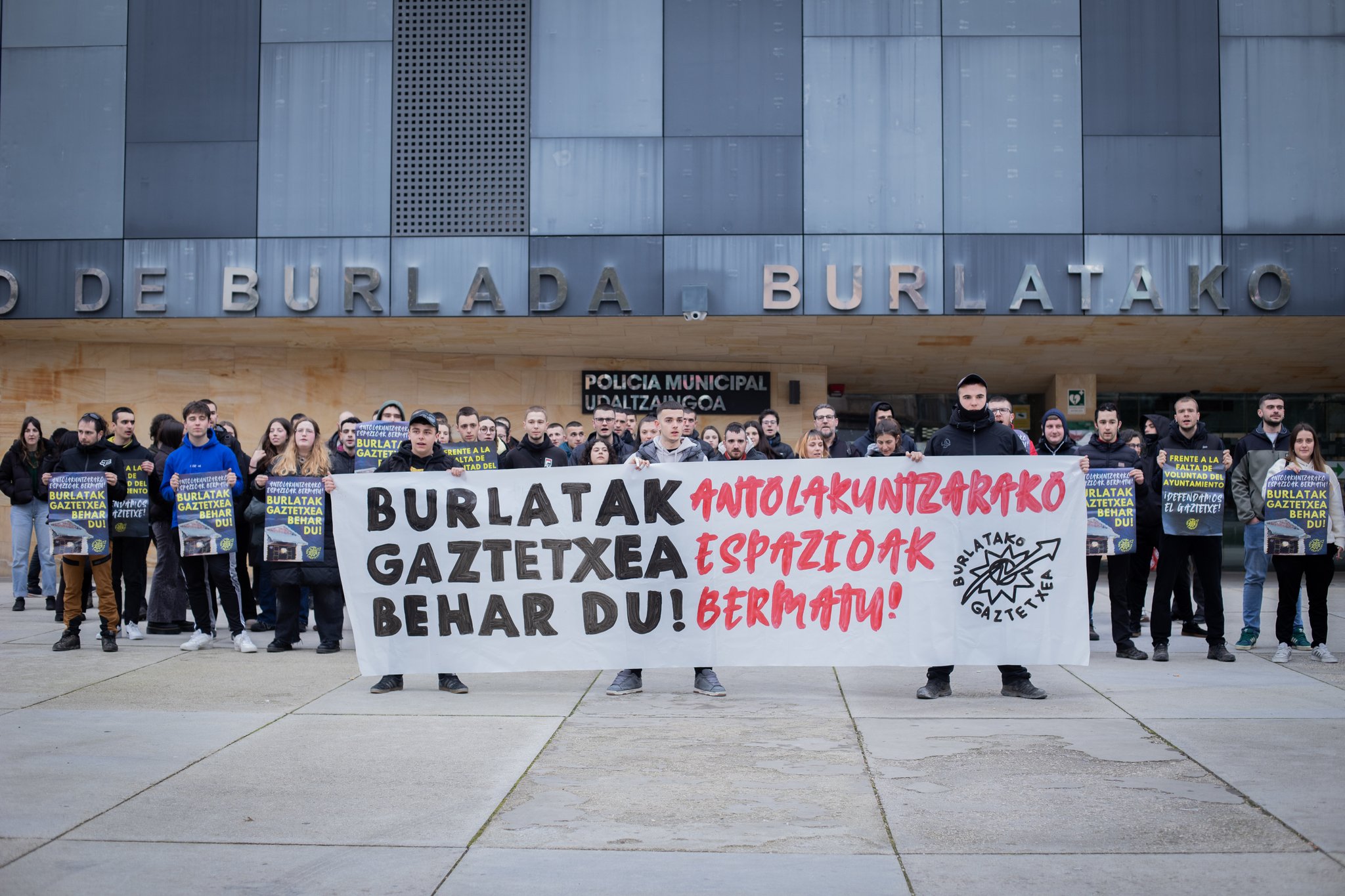

EH Bildu agintean dagoen udalak gaztetxearen etorkizuna ziurtatzeko aterabide bat adosteari "uko" egin diola salatu du Burlatako Gazte Asanbladak. Beste hainbat gaztek udaletxe kanpoan kanpatu dute, eta goizean zehar bertara hurbiltzeko dei egin dute.

Iruñerrian bat egin dute hainbat Gazte Asanbladak, Burlatako Gaztetxearen alde. Etxarriren desalojoa gelditzera deitzeko, bestalde, manifestazio bat antolatu dute Bilbon hilaren 28rako.

Asteburu honetan hasiko da Gaztetxeak Bertsotan egitasmo berria, Itsasun, eta zazpi kanporaketa izango ditu Euskal Herriko ondorengo hauetan: Hernanin, Mutrikun, Altsasun, Bilboko 7katun eta Gasteizen. Iragartzeko dago oraindik finala. Sariketa berezia izango da: 24 gaztez... [+]

Festa egiteko musika eta kontzertu eskaintza ez ezik, erakusketak, hitzaldiak, zine eta antzerki ikuskizunak eta zientoka ekintza kultural antolatu dituzte eragile ugarik Martxoaren 8aren bueltarako. Artikulu honetan, bilduma moduan, zokorrak gisa miatuko ditugu Euskal Herriko... [+]