The future of the Spanish nuclear power stations is being played here.

- If it complies with what was announced in February, the Spanish Nuclear Safety Council will release before the end of the year a report on the request of the Garoña plant. If it were favourable, and it might be so, the plant owners would be closer to what seems to be their real objective: to extend the life of the whole nuclear park. And it's that reactivating Garoña, who slept since 2012, wouldn't be a good business for them. In any case, it is difficult to know what is going to happen.

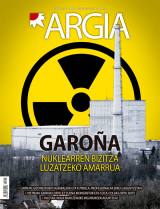

It is not easy to understand what is happening with the Garoña nuclear power plant in recent years. The plant has been in lockdown since December 2012 and the operating period was exhausted by law in 2013. According to this, it should be in the process of dismantling, but its owner, Nuclenor, half of whom was involved by Iberdrola and Endesa, requested in 2014 the authorisation to extend the life of the plant, in compliance with the legislation of the Spanish Government ad hoc. Since then, Nuclenor is awaiting a response from the Ministry of Industry. Prior to this, it is a prerequisite that the Nuclear Safety Council (CSN) endorses the company’s request.

The CSN has already announced that this autumn it will issue a favourable or unfavourable report on the suspension of military activity. In view of the path taken so far, it is possible to bet that Garoña gives the green light to its reoperation, “but that is not entirely certain”, says the professor of the UPV/EHU Aitor Urresti, who follows the subject with great attention. “The report is lagging a long way behind,” he explains, “and that means that within the CSN things are not so clear; it is true that the PP has a majority in the Council and that in that sense it can be expected yes, but…”.

What does Nuclenor want?

In any event, the CSN will also have to report favourably on the conduct of the companies that own the plant and the Spanish Government after completion. It must be borne in mind that, in this respect, all the groups in the Congress of Deputies, except the pp and some parties with very low representation, have opposed the reopening of Garoña. As far as Nuclenor is concerned, it appears to be in total contradiction. Garoña has applied for an operating licence until 2031, but is making no effort to re-launch the plant in compliance with the conditions imposed by the CSN.

The explanation is simple: The improvements to be made in Garoña, some derived from the regulations that emerged after the Fukushima accident, others directly related to the design of the plant, are complex and costly, and Nuclenor’s partners are not in the best position to address them. Or in other words, they're not worth it, Garoña isn't very big and doesn't make big profits. One of Nuclenor's partners, Iberdrola, has hinted, through the mouth of the president, Ignacio Sánchez Galán, that he has no interest in relocating Garoña. So why have you asked the plant to extend the licence until the age of 60?

The decision to extend the life of the entire Spanish nuclear park until 2012-2028, and the plants are the same as those in Garoña

Many of those who have closely followed this endless pamphlet, as well as nuclear anti-energy, have a clear answer to the previous question: Garoña is the letter that companies in the electricity sector are playing to extend the life of other nuclear plants in the Spanish State from 40 to 60 years.

The PSOE did not dare

In all Spanish legislation you will not find a single sentence specifying the maximum duration of nuclear power plants. Traditionally, everyone has remembered that the barrier should be put in 40 years, precisely because the power plants in the Spanish state were designed to maintain that time. The PSOE had already committed itself to introducing the 40-year border into the legislation and had already had the opportunity to do so in the 2008-2011 mandate, but it did not finally do so, so the regulation leaves the decision to the government and the CSN.

Garoña was built in 1970 and started a year later. In that mandate of the PSOE it was the oldest plant in the State in which they worked. The business licence was due to expire in 2009, so very close to the 40 years of the plant, but the Ministry of Industry, instead of ordering the closure at that time, granted Nuclenor a licence for another four years until 2013, the date the company had requested until 2019, the deadline for the closure of Garoña, at the age of 42. This left the door open for the next government to prolong the life of Garoña, especially if it is the pp, which is profoundly favorable to nuclear.

Red carpet in charge of pp

In June 2012, Mariano Rajoy was the tenant of the Moncloa and the pp had an absolute majority in the Spanish Parliament. On the 29th, the Ministry of Industry revoked the three-year order and gave Nuclenor the possibility to request a new authorisation for another six years (until 2019). However, Nuclenor did not avail himself of the facilities provided by the Government, which passed the legal deadline to request the extension. Therefore, the procedure for terminating the operation of the plant was initiated.

Under normal conditions, this procedure would be extended by about one year, after which the ownership of Garoña would be transferred to the State to undertake the demolition of the plant through the public nuclear waste management company (Enresa). At the moment, none of this has, of course, happened.

In the next few months, a lot of things happened. First, in December 2012, Nuclenor stopped broadcasting to the electricity grid the energy produced by Garoña individually and without authorisation, on the basis of economic reasons. A few days later, and with the same argument, it was Nuclenor himself who called for the cessation of the exploitation of Garoña, although by then he had on the table an order from the Ministry that had to comply half a year later. The fact is that Nuclenor explicitly stated that he was being asked for economic reasons and not for security reasons. The importance of such precision was soon known.

Custom-made regulations of Garoña

On 5 July 2013, the Ministry of Industry issued the order for the end of operation of the Garoña nuclear power plant, in compliance with the terms of the mandate of the PSOE. The Order, however, clearly indicated that the only cause of interruption of exploitation was economic. On the same day, the Government opened the door to the possibility of reopening the plant in the future. In particular, the draft Royal Decree on Nuclear Fuel Management was amended several times by the Ministry. These changes would allow nuclear power stations where they would have ceased their activity to resume operation if the reason for the cessation was not related to safety and operating authorisation was requested within one year. The text was only lacking in expressly quoting the name of Garoña.

Araba Garoñarik Gabe platform called for a demonstration on 28 February 2015 to call for the final closure of the Garoña nuclear power plant. (Ed. : Raul Bogajo / Argazki Press)

The new royal decree enters into force in February 2014. In May, Nuclenor asked the Ministry of Industry for authorisation to extend Garoña’s activity until 2031, taking advantage of the operation. “It was absolutely unusual,” explains Raquel Mucha, who was responsible for the campaign of the nuclear power plants in Greenpeace Spain, “because until then the authorizations of all nuclear power plants were requested and granted for ten years, precisely in line with the safety inspections, and that was required for seventeen years.” For the first time, the request of a Spanish central to extend its life until the age of 60 was on the table. And it's still there.

The CSN opens the way

Nuclenor's request for authorization came to the CSN, which is the one who must give the approval first of all, always from the point of view of safety. In July 2014, the CSN Plenary Session approved a Complementary Technical Instruction (OC) on Garoña. In short, NATO details the documentation to be submitted and the requirements to be fulfilled by Nuclenor in relation to his request. Thus, the CSN began a procedure of reopening of Garoña still incomplete. The curious thing is that its technicians have had to work in two opposite directions over these two years: on the one hand, analyzing the request for the reopening of the plant and, on the other, performing the formalities corresponding to the completion of its operation.

NATO on Garoña was not unanimously approved by the CSN. One of the five members of the plenary session, former PSOE Environment Minister Cristina Narbona, voted against the non-legislative proposal. It is worth reading the explanations he gave on the reasons for his vote: “The CSN Plenary Session took the decision to approve NATO without discussing in depth, either from a technical or legal point of view, the consequences that Nuclenor’s request may have, despite the unprecedented situation in the history of the CSN.”

What are the consequences of authorisation at the age of 60?

According to the former minister, it has not been seriously analysed what safety benefits a nuclear power plant can bring for 60 years, given that one of the consequences of its extension is to increase the amount of nuclear waste. Narbonne has voted against all the resolutions adopted by the CSN on the reopening of Garoña and has called for this procedure to be put to a standstill until the entity has had a thorough debate and exposes it to public opinion on the consequences of Nuclenor's authorization.

Former Environment Minister and critical member of the CSN, Cristina Narbona, believes that no serious analysis has been made of the safety implications of extending the life of a plant at the age of 60.

Coinciding with the request of Cristina Narbona, in February 2016, all parliamentary groups of the Spanish Congress, except the PP, sent a letter to the CSN asking him to desist from the process of reopening Garoña until “forming a new government”. As the groups explained in the letter, the favourable report of the CSN and the authorization of the reopening of Garoña by the incumbent Government would pose a great risk: if the new Government decided to maintain the order for the end of exploitation in force, which is the permanent cessation of Garoña, Nuclenor could claim compensation and not little. Obviously, this risk has not yet disappeared, among other reasons because the CSN has not listened to the letter.

Main party in the next decade

The granting of the authorisation for the relocation of Garoña may set a precedent for the future. There are currently seven nuclear reactors working in the Spanish State, distributed among the five nuclear power stations that are deployed. All of them are more powerful than Garoña's, more than double. And most importantly, they're also slowly approaching the 40-year-old border.

The Almaraz-I reactor in Cáceres will be the first to expire in 2021. The youngest, Trillo, in Guadalajara, will take her turn in 2028. In other words, a decision will have to be taken within seven years on the extension of the life of the entire Spanish nuclear park. One of the two patrons of Garoña, Iberdrola, participates in all the plants and in some cases in the whole plant. Endesa can say almost the same thing: it is involved in all but one.

With this data we can better understand what Equo-Podemos Member Juan López de Uralde said in the Congress Industry Committee on 19 October: The former director of Greenpeace Spain described as theatre the procedure being carried out at the CSN to renew Garoña’s license. “Its owners are not interested in reopening it either, they are only using it to extend the life of other plants.”

López de Uralde took advantage of his hearing to inform CSN President Fernando Martí about the consequences of the humanitarian crisis. Martí admitted that Nuclenor is not complying with the plan to improve the reopening of the plant commissioned by the CSN, since it has been more than a year since the deadline for implementing these improvements was exhausted. "If that is the case, why do you not simply refuse the reopening of Garoña? PNV parliamentarian Pedro Azpiazu asked Martín. The chairman of the CSN replied that this would be prevaricating and stressed that his organization is technical, not political.

The pp is done with the control of the CSN

Marti may well have recalled the harsh criticism of the CSN over the past few years, when he said so. In theory, the nuclear safety agency is completely independent of the other institutions and, in particular, of the Government. The supreme decision-making body, the plenary, is composed of five members proposed by the political parties through the Congress of Deputies. In fact, in theory, the CSN just has to be accountable to Congress.

Doubts about their independence are not the subject of last night, but the toughest criticisms have been received by the CSN in recent years, especially by two players of the pp. One is the very appointment of Fernando Martín: He was Secretary of State for Energy until the day before he took office as president of the CSN, and we are literally using the word “bezpera”. This happened in December 2012. Although the appointment is legal, it is clear that independence from Martin’s government is very doubtful.

The second game of pp took place in October 2015. The popular, thanks to the absolute majority they held, for the first time broke the traditional balance in the formation of the CSN. In particular, an adviser to his rope, Javier Dies, was appointed in place of Antonio Gurguí from CIU, who was due to leave office after the deadline. The decision was implemented by a government decree, as the majority of the Congressional Industry Committee voted against the appointment. Since then, there are three PSOE advisors and two PSOE counselors at the CSN, which breaks with the tradition that both parties had the same number of advisors.

The regulator is regulating less and less

In recent months, the internal voices of the CSN, which question independence, have been the most prominent. An association of CSN technicians (ASTECSN), founded in 2015, has filed serious complaints against the management of Fernando Martí according to the ASTECSN, which is undermining the regulatory role of the CSN since Marti rules. It is accused, among other things, of changing safety measurement procedures, as with the new systems it is more difficult to analyse all incidents.

ASTECSN also complains that they have been dismissed senior technicians who have been working for many years and have been replaced by trusted people from the new authorities. One of the representatives is precisely in charge of analysing the Garoña power plant, which occurred in 2013. According to internal sources of the association, “the superior technicians who have put in place, in general, coincide with the criteria of the current president, that is, with deregulation”.

2009-7-3: Espainiako Industria Ministerioak, artean PSOEren agindupean, 2013an finkatu zuen Garoñaren ustiapenaren amaiera. Hala, 42 urtera arte luzatu zuen zentralaren bizitza, ohiko 40en ordez.

2012-6-29: Industria Ministerioak, ordurako PPren esku, aurreko agindua baliogabetu eta aukera eman zion Nuclenorri, zentralaren ugazabari, ustiapen baimen berria eskatzeko 2019ra bitarte. Nuclenorrek irailaren 5a zuen horretarako epemuga, baina denbora gehiago eskatu zuen. Ministerioak ez zion eman, eta Garoñaren ustiapena 2013an bertan behera uzteko prozedura hasi zen.

2012-12-16: Nuclenorrek, bere kasa eta baimenik gabe, Garoñak sortutako energia sare elektrikora jaulkitzeari utzi zion, “arrazoi ekonomikoak” argudiatuta. Hala jokatzeagatik 18,4 milioiko isuna ezarri zioten 2014an.

2013-7-5: Industria Ministerioak Garoñaren ustiapena amaitzeko agindua eman zuen, eta horixe da zentralaren lege-egoera une honetan. Alabaina, egun berean, ordu gutxira, Ministerioak tramiteak hasi zituen erregai nuklearrari buruzko errege dekretuan aldaketak ezartze aldera. Aldaketa nagusia zen arrazoi ekonomikoengatik –eta ez segurtasunarekin lotutakoengatik– bere jarduera etendako zentralei berriz lizentzia eskatzeko aukera emango zitzaiela. Testu proposamen berriari Garoñaren izena espresuki aipatzea baino ez zitzaion falta. Dekretua 2014ko otsailean onartu zen.

2014-5-27: Nuclenorrek, aipatutako dekretuan oinarrituta, Garoñaren bizitza 2031ra arte luzatzeko baimena eskatu zion Ministerioari.

2014-7-30: CSNk Argibide Tekniko Osagarria dokumentua onartu zuen, Garoñako zentrala berriz lanean hasteko bete beharreko baldintzak zehazten dituena. Geroztik eta gaur arte, CSNk hainbat erabaki hartu ditu Garoñan egin beharreko hobekuntzei buruz, betiere zentralaren irekiera ahalbidetze aldera.

2016-2-3: CSNk ontzat eman zituen Nuclenorrek Garoñan egindako hainbat hobekuntza, 2014ko uztailaren 30eko Argibide Tekniko Osagarrian jasotakoak. Halaber, iragarri zuen Garoña berrirekitzeari buruzko behin betiko txostena 2016ko bigarren seihilekoan igorriko ziola Industria Ministerioari.

Garoñako zentrala berriro lanean hasteko Nuclenorrek bete beharko lituzkeen baldintzetako bat ez datorkio CSNren eskariz, Ebroko Ur Konfederazioaren aldetik baizik. Kontuan izan behar da zentralak ibai horretatik hartzen duela funtzionatzeko behar duen ura.

2013ko uztailean –ordurako zentrala geldi zegoen–, Konfederazioak esan zuen Garoñak, berriz lanean hastekotan, neurri zorrotzagoak beharko zituela Ebro ibaiko uren erabilerari dagokionez. Zehazki, esan zuen zentralak ibaira bueltatzen duen erabilitako ura beroegia dela, eta horrek ingurumen arazoak sortzen dituela.

Hori saihesteko hozte-dorre berria eraikitzeko baldintza ezarri zion Ur Konfederazioak Nuclenorri. CSNren eta Ministerioaren onespen guztiak lortuta ere, Garoñak ezinbestean egin beharko luke obra hori, funtzionatu ahal izateko. Eta inbertsioa ez da txikia. Beste alternatiba potentzia baxuagoan lan egitea litzateke.

Garoña behin betiko itxi? Demokrazia energetikoa eta energia sozialak izenburuarekin solasaldia egingo da Gasteizko Oihaneder Euskararen Etxean, azaroaren 16an. ARGIAk bertan paratuko duen Trantsizioak erakusketari lotutako ekitaldia izango da. Parte hartzaileak Aitor Urresti EHUko irakaslea eta Patxi Alaña Bizkaiko Garoñaren Kontrako Foroko kidea izango dira, eta Unai Brea ARGIAko kazetaria arituko da moderatzaile lanetan. Arratsaldeko 19:00etan hasiko da solasaldia.

Azaroaren 3tik 24ra izango da Oihanederren Trantsizioak. ARGIAren begirada lau hamarkadatako eraldaketei (1976-2016) argazki erakusketa. Garoñari buruzkoa ez ezik, hainbat ekitaldi egingo dira hari lotuta.

How to close Txernobyl? How to close Fukushima? These two nuclear power plants, after suffering accidents, are still "alive" and no one is calling for their closure. The first has been covered and covered, and the solution has been entrusted to the technological advances that the... [+]