"Today it seems we don't trust things to change."

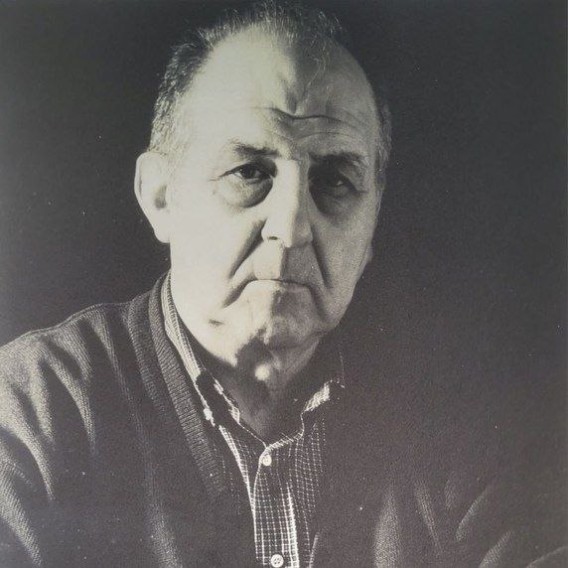

- The researcher tells us about the time when the working-class identity developed in the neighborhoods and factories gained strength to change the world a little.

He has analyzed the labor movement in the region of Pamplona. Why have you later gone deeper into the role of women?

In my thesis I didn't look particularly at this issue and then I thought why I didn't do it. I did 50 interviews for the thesis and only five of them for women. It is true that women who worked outside the home were much less than they were now and that in organized labor movements were very few, but it must be understood that in the struggle of workers women had different ways of participating. To participate in these kinds of movements, it is not necessary to be a prominent leader of the Workers Commissions. I started researching that thread, and I saw that the role of women in neighborhoods had been very important. More than in the labor movements, women were dedicated to the demands and movements of the neighborhood. Why do we think that the striking man is much more important than the woman who takes over the family while she doesn't charge? Or the woman who takes the food to the mouth of the mine? Why do we give more prominence to some forms of participation if the others are also fundamental? The work of women was essential for the workers to be there and for the strikes to be maintained. And another question, if that function is so important, why have women always done it?

How did workers' identity emerge in the Region of Pamplona?

In the 1950s, a lot of people came from the Navarros villages to Pamplona. With the industrialization of the city, exterior neighborhoods such as Chantrea and Rochapea began to grow. Most of the workers were engaged in the metal and automotive industries. In addition to the neighborhood, they shared the same socioeconomic reality and life, all of which contributed to the creation of social networks and a working identity.

Networks of relationships were created in different areas and exchanges of ideas took place between them. To this must be added the contribution of emigrants from Andalusia and other places in the 1960s. Many of them had suffered severe repression and maintained a certain relationship with workers ' organizations. In the fierce times against Franco, these groups of workers defined their identity.

You are a chantre. When you looked at creating neighborhood communities, why did you choose Txantrea as an example?

Because the chantre is a very good model. It's a field made by the workers. It is very interesting to analyze the way of life experienced, how relationships emerged. The people who came from the agricultural world created a community way of life. Values such as auzolan or solidarity were highly internalized.

The construction process of the neighborhood was very special. The workers who would live here began to raise their houses in the 1950s. They built the neighborhood and lived in the neighborhood. This shows how the relationships started to emerge and how they extended to all areas of the neighborhood's life. Solidarity was maintained and passed on to future generations as a positive value. They felt proud of the neighborhood they had created themselves. In addition to the house, they built relationship spaces and networks. It is no coincidence that shortly after the creation of the neighborhood a rock was opened, the first that emerged outside the Casco Viejo de Pamplona.

The Board of Trustees Francisco Franco had agreements with several construction companies in Pamplona so that their workers could build their houses. Once the working day was over, a few more hours a day were devoted to building their houses. The Board placed the materials, tools, plans and technical work and the workers the workforce. The streets were divided by companies and groups. All the houses were made between them and then they were drawn between the participants. Thus, they assured that all houses would be the same. Subsequently, those who were not construction workers also had the opportunity to participate in this system. Later came the houses built by the board itself, such as the current ones of official protection. It's a very interesting collective experience. Thus, homogeneous population groups emerged, working-class neighborhoods.

Hence Txantrea's current reputation?

I would say yes. It is a very nice and romantic past. From that time onwards, there are ways of relating and values. Most of them worked in the same factories and there were two-way relationships between the factory and the neighborhood.

What was the labor movement of the Region of Pamplona during the Franco regime?

Very active. The 1958 Collective Agreement Act allowed the grouping of workers to improve their working conditions. In the 1960s, many workers’ movements emerged. Among them, Christian natures were of great importance. They put into circulation concepts like social justice. The movements that emerged from the bottom were the creation of Workers' Commissions and other large workers' organizations.

At the end of Franco the movement was very important in the Region of Pamplona. It was solidarity with the workers of the Iberian Motor in 1973 or the terrible strikes of 11 December 1974. In 1975, the confinement of the miners of Potas was also a milestone. The strikes extended immensely. Eaton was on strike for 47 days and 45 in Imasa. Given the low population of Navarre and the delay with which industrialization began here, this phenomenon is very interesting.

Why was it so active?

At first, the neighborhoods were key to consolidating a dense workforce in the Region of Pamplona. Later, in the 1970s, the factories were the succession of previous labor movements. True engine of protests and demands. The creation of commissions in factories, the negotiation of collective agreements, the work of several workers within the structures of the Vertical Union and the conflicts themselves gave opportunities, and the workers took advantage of those opportunities to work and work together.

Within the factories of Pamplona a new and notable organizational model was created that extended to the whole of Navarre and materialized in some of the most significant events of the last years of the dictatorship.

Were most workers anti-Francoist?

Anti-Franco was one of the components of the workers' identity. The workers believed that their socioeconomic demands had no future as long as the dictatorship lasted. It was a class identity and an anti-Francoist character. They wanted to delegitimize capitalism and promote alternatives on either side. In this process of identity creation, the workers appropriated their transformative capacity and therefore lived the last years of the dictatorship and the transition as a great opportunity for social transformation.

What conclusions has been reached with regard to the current reality?

These are different historical times. We have to think that the workers of those years were able during the dictatorship, after strong repression, to conquer and create spaces and to promote actions. Today it seems that we have no confidence in changing things. So there was. We should see what kinds of fighting we can set in motion, although it is not easy. But if it was possible before, why not now? Things were done because the struggle was hard.

He works at the office that has opened in Pamplona to collect the testimonies of Franco. What is the objective?

The City Council has launched the initiative with the collaboration of a group of researchers from the Public University of Navarra. The objective is to collect as many data as possible about the people who were victimized in Pamplona and to use them to participate in the lawsuit against the crimes of Francoism held in Argentina.

Since May we have been collecting information, testimonies and documentation. We wanted it to be a point of reference for people, a place of information, of expressing concern and of liberation. A lot of people have come to ask and to give information.

Therapeutic by the way?

I think so. A lot of people need to be heard. For many years there has been great silence, and despite the work of the groups in favour of memory recovery, there is still that need. People appreciate having the opportunity to tell the story of their family in a project supported by an institution.

However, some do not consider themselves repressive, because they are well assumed that the time was like this and that life was like this. But in addition to firing and incarceration, there are many very subtle forms of repression that are not often considered repressive.

For example?

Socio-economic repression. Dismissing workers on strike or not finding work as a son of a Republican or a repressive. The data remains in many cases in the number of deaths, but the families of the deceased continued and had very hard lives. A lot of people stayed in misery. For example, many people have told us that they have never seen their grandmother smile or that they always remember their mother with sadness. Listening to some stories is very hard.

People who experienced the post-war crackdown on the front line are dying, so it's very important to do this work as soon as possible.

The crown of Ereinotz is being removed from the Deputation, Mola and Sanjurjo will soon be taken out of the graves… the issue is on the surface.

You have to see how the issue still raises dust. That means things are changing, but some positions are not so much. The issue is not yet standardized.

“Tesian ez nuen egin nahi langileen mugimenduen datu bilketa hutsa. Lan oso onak eginak zeuden aldez aurretik. Nik jakin nahi nuen zergatik iristen diren Nafarroako langileak horren borrokalari izatera, zerk eraman zituen horren gatazka gogorrak burutzera frankismo amaieran. Nola sortu zen klase kontzientzia zuen langileria”.

“Auzoetan sortu ziren gizarte-sareek (kirol elkarteek, gizarte guneek eta aisialdirako guneek) eta mugimendu apostoliko laikoek langile nortasun komun bat sortzen lagundu zuten. Besteak beste, elkartasuna, senidetasuna, kolektibotasuna, berdintasuna, injustiziaren aurkako matxinatzea eta antikapitalismoa ziren oinarria”.

Public education teachers have the need and the right to update and improve the work agreement that has not been renewed in fifteen years. For this, we should be immersed in a real negotiation, but the reality is deplorable. In a negotiation, the agreement of all parties must be... [+]

Economists love the charts that represent the behaviors of the markets, which are curves. I was struck by the analogy of author Cory Doctorow in the article “The future of Amazon coders is the present of Amazon warehouse workers” on the Pluralistic website. He researches the... [+]