The European Union adapts its legislation to limit mercury pollution

- In 2013, the United Nations agreed on the Minamata Convention with the aim of responding to mercury pollution around the world. Now, the European Commission, on the basis of the agreement, is taking steps to renew its own legislation. Several groups consider that the proposed law is not sufficient and have been in favour of the implementation of the existing legislation.

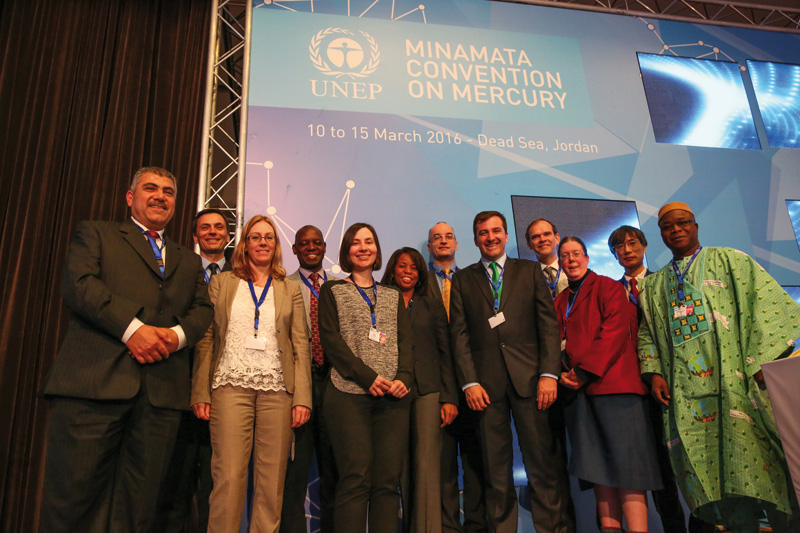

Concerned about the negative effects of mercury on human health and the environment, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) conducted a first overall assessment of mercury in 2002. The group renewed its conclusions in 2013. However, in 2009, the UNEP Governing Board agreed on a legally binding international agreement that led to the creation of the Minamata Convention in October 2013 and under the umbrella of the UN.

To combat mercury pollution, the international agreement took the name of the Japanese city of Minamata. In the middle of the twentieth century, a large number of inhabitants of this city were poisoned by eating fish and shellfish contaminated with mercury. Precisely because of this fact, the neurological syndrome that causes severe mercury poisoning is called Minamata's disease.

Immediately after the presentation of the Convention, it was signed by several Member States. Currently, the international agreement on mercury has 128 signatories. At the time approved, in 2013, it was expected to be binding by 2016. However, these signatures do not oblige signatory States to comply with their own regulations and instructions. For the Minamata Convention to become binding, the agreement has to be ratified by 50 countries, while at the time of drafting only 29. In this regard, he recalled that, although the Spanish and French States have a signed agreement, they have not yet taken the step of ratification.

Minamata to European legislation

At present, EU legislation prohibits the export of pure mercury and mercury compounds, prevents the use of mercury in certain products and seeks to respond to the pollution caused by mercury. However, there are some differences between the Minamata Convention and existing EU legislation. With the aim of addressing these shortcomings, on 2 February 2016 the European Commission presented two proposals for the adoption of the Minamata Agreement: one, the ratification of the Convention on behalf of the European Union or the second, the proposal for a new regulation to deal with mercury. According to this last point, the Commission is preparing a new proposal for a law, which could be appealed.

So far, the 2008 Mercury Export Ban Regulation is the main legal provision in the European Union in this area. This law prohibited the export of mercury by the EU from 2011 onwards. In particular, the ban on exporting metal compounds and their mixtures – in which at least 95% of the weight is mercury – has since been banned, while the ban does not affect products containing other mercury.

Proposals to adapt EU legislation to Minamata include a ban on the import of mercury for small-scale artisanal and gold mining uses. In addition, by 2018, dental amalgam can only be used in encapsulated form and by the end of 2021 it has been proposed the gradual elimination of the use of dental amalgam. The new proposal also aims to regulate the export, import and manufacture of products containing a certain quantity of mercury and, at the same time, to avoid new uses of mercury in the market.

Criticisms of the proposed law

Following on from the draft legislation, the European Environment Office has criticised the European Commission’s submission of an unambitious proposal. Among other things, they have called for a tightening of the conditions for prohibiting the export of products with additional mercury and for the phasing out of the use of mercury in dentistry and industrial processes. Sweden has also criticised the proposal before the EU Environment Council, considering that it has little ambition, especially as regards dental amalgam.

European Union legislation prohibits the export of mercury and its use in certain products

The parliamentary group of the European United Left/North Green Left has also criticised the European Commission’s proposed law. The group representative, the German MEP Stefan Eck, has accused the Commission of a "minimalist" approach and lack of ambition in the face of mercury pollution and the negative effects that this element generates on public health. “The Commission’s proposal has been the victim of ‘better regulation’,” says Eck, criticising Jean-Claude Juncker’s strategy, which aims to simplify regulatory processes by cutting red tape. “The choice of the most cost-effective method is harmful and incompatible with the Minamata Convention. It is clear that the proposal does not pay enough attention to the public interest,” the German parliamentarian said.

According to Elena Lymberidi-Settimore, coordinator of the Zero Mercury Campaign, launched by several environmental groups, “the Commission has presented a proposal based on the minimums; on the pretext of improving legislation, the proposal rejects the scientific findings evaluating the public consultation, the voice of the most advanced industries and the impact of mercury.”

The European Green Party supports the ban on the import of mercury from non-EU countries, as set out in the proposed law. Equo’s spokesman in the European Parliament, Florent Marcellesi, explained that “the Commission’s proposed legislation, although more ambitious than the Minamata Convention, would mean maintaining the right to export mercury-containing products outside the EU, despite the limitations imposed on them in the European internal market”. According to Marcellesi, “this policy is unacceptable because people’s health has the same value in European countries and outside Europe.”

According to Leticia Baselga of Ekologistak Martxan, the Minamata Convention itself is not sufficient to deal with the problem of mercury. According to Baselga, “the agreement falls short because it takes too long to respond to the measures it proposes.” However, in his view, the problem with mercury is illegal trade. Thus, the new mercury mines appearing in Indonesia, Mexico and several East Asian countries are becoming an important shopping centre. This activity feeds the global demand for mercury from artisanal gold mining, especially in Asia and Latin America.

Mercury use in Europe

Europe accounts for 6% of global mercury emissions from human use. However, according to data published by the European Environment Agency in 2015, mercury emissions from EU Member States decreased by 74% between 1990 and 2013. Poland (17.2%), Germany (17%), Italy (13.4%), the United Kingdom (10.1%) and the Spanish state (8.9%) are the main pollutants of mercury in the EU.

Europe accounts for 6% of global mercury emissions from human use, the main sources being coal-fired power plants and the chlorine industry.

In Europe, the main sources of mercury pollution are coal-fired power plants and the chlorine industry. Along with them, mining and waste disposal also have a huge impact.

In the European Union there is an alert system for food and feed called RASFF. According to their data, in 2015, 138 warnings were issued for heavy metals, including mercury, cadmium, lead and arsenic, among others. However, 104 cases were due to the appearance of mercury in fish and other fishery products. It should be noted that 65% of the notices for having more mercury than allowed in fish corresponded to a single state: the Spanish state

Artisanal gold miners, using mercury.

Dental amalgam, proposed by the European Commission that can only be used in encapsulated form by 2018 and that its use be phased out until 2021.

Hondakinak erretzea da merkurioa ingurunera zabaltzeko errudun nagusietakoa. Erraustegien tximiniek merkurioa jaurtitzen dute airera, baita zementu-fabrikek ere. Ekologistak Martxaneko Leticia Baselgaren esanetan, “erraustegiak arriskutsuak badira ere, zementu-fabriketako tximinietatik zabaltzen dena gutxiago zaintzen da”.

Merkurioa zabaltzearen arrazoia da erraustegietan erretzen diren materialetako metal pisutsuak ez direla suntsitzen errauste prozesuaren bidez. Baselgaren arabera, horixe gertatzen da adibidez erretzen diren pilekin. Greenpeacek 2001. urtean argitaratutako txosten batean argitzen denez, erraustegietako tximinietatik kanporatzen diren metal pisutsuen maila asko gutxitzea lortu da azken urteetan teknologiaren ondorioz, merkurioaren kasuan izan ezik.

Erraustegien adibidea gurera ekarrita, Bizkaiko Zabalgarbi erraustegiak, esaterako, 2012. urte osoan 1.484 gramo merkurio zabaldu zituen airera tximinia nagusitik. Isuri hori Bilboko biztanleen artean banatuz gero, biztanle bakoitzak 4,27 miligramo merkurio irentsiko lituzke urtean. Datu esanguratsua, Osasunaren Mundu Erakundeak 70 kiloko pertsona batentzat urteko 6,06 miligramoko merkurio kopurua baitu zehaztuta onargarri moduan.

Energiaren Nazioarteko Agentziak (IEA) astelehenean argitaratutako txostenaren arabera, %2,2 igo da energia eskaria 2024an aurreko urtearekin alderatuta, besteak beste, egiturazko arrazoi hauengatik: beroari aurre egiteko argindar gehiago erabili beharra, industriaren kontsumoa... [+]

Kutsatzaile kimiko toxikoak hauteman dituzte Iratiko oihaneko liken eta goroldioetan. Ikerketan ondorioztatu dute kutsatzaile horietako batzuk inguruko hiriguneetatik iristen direla, beste batzuk nekazaritzan egiten diren erreketetatik, eta, azkenik, beste batzuk duela zenbait... [+]

Lurrak guri zuhaitzak eman, eta guk lurrari egurra. Egungo bizimoldea bideraezina dela ikusita, Suitzako Alderdi Berdearen gazte adarrak galdeketara deitu ditu herritarrak, “garapen” ekonomikoa planetaren mugen gainetik jarri ala ez erabakitzeko. Izan ere, mundu... [+]

Ur kontaminatua ur mineral eta ur natural gisa saltzen aritu dira urte luzeetan Nestlé eta Sources Alma multinazional frantsesak. Legez kanpoko filtrazioak, iturburuko ura txorrotakoarekin nahasi izana... kontsumitzaileen osagarria bigarren mailan jarri eta bere interes... [+]

Greenpeaceko kideak Dakota Acces oliobidearen aurka protesta egiteagatik auzipetu dituzte eta astelehenean aztertu du salaketa Dakotako auzitegiak. AEBko Greenpeacek gaiaren inguruan jasango duen bigarren epaiketa izango da, lehenengo kasua epaile federal batek bota zuen atzera... [+]