General Strike in Vitoria

- When on 18 July 1936 the military rose up, the response was immediate and the left-wing workers used their main weapon: the general strike. In some places, like in San Sebastian, anarchists resisted. In Vitoria-Gasteiz, the general strike lasted for several days, but it was too late, without weapons and with the incorporation of all Álava to Mola, the resistance of the capital and its memory were lost forever.

The barricades did not occur in the streets of Vitoria-Gasteiz 80 years ago, there were no demonstrations or Republican proklamas, but the victory of the golfers in the Alavesa capital was not clear until several days after the war was declared. On Monday, July 20, communists, socialists and anarchists called the strike workers and the shops and workshops of the city remained closed. On July 23, an airplane launched octavillas to the Workers! with the title: “For the peace and tranquillity of your families, honest workers, take with your support this civic and military movement, which comes to gather the corruption and the garbage that drowned us.”

What had actually happened in the early days of the uprising? Did the vitorians receive with their arms open to the cottage cheese flocks of the province? In the early hours of Monday, we didn't even hear steam in the streets: strike, fear, disinformation... There are indications that in Vitoria the republican conscience and the workers' organization were fairly rooted. But the civilian governor did not want to give weapons to the members of the Popular Front and the PNV, and once the command was in the hands of the military, an order had been issued to shoot all the people who were in “suspicious position.” The strike failed.

Since the beginning of

the time of the machine and the work became merchandise, the workers have used their own treasure as the main weapon of improvement: not going to work. The general strike has had many meanings throughout history and at the beginning of the twentieth century it has acquired a revolutionary tone. Anarchists and communists saw this as a first step towards emancipation and it is no wonder that when they learned that in 1936 military forces were set up in Morocco, stoppages were convened in several cities, even if it was a weekend.

This was the case in Madrid and Barcelona. In the latter, in view of the doubts and lack of command of the Generalitat in Companys, the workers assaulted several warehouses in the city and seized weapons. In Barcelona, the CNT organization was very strong, as at least 20,000 militiamen were prepared for the revolution. Hearing the mermaids of the tissue factories, the rebel soldiers heading from the barracks to the city centre, accompanied by the assault guards, were thrown as a slogan for the strike.

The workers played the same role in other places where a solid industrial fabric existed, such as Miranda de Ebro. The arrival of the railroad to the town, located on the border with Álava, boosted the workers character of the natives. On the eve of the uprising on July 18, the women protested that the bread was at 0.60 pesetas, and also attacked the flour factory. The next day, the people were left in the hands of the railways, until a detachment of civil guards attacked them. Many young people fled through the Zadorra River, but when they arrived at Zambrana they were awaiting the Requetés and Falangists, guided by a cure, and they were shot to death. At least seven were killed, one of the first massacres in Basque lands.

In Vitoria, however, at the beginning of the twentieth century there were hardly any major factories except the old Metallurgical Vitoriana Meta, where agricultural machinery was manufactured. Vitoria, like Pamplona, was the capital of a “new Covadonga”, a conqueror germ dominated by the rural world, carlism and the conservative bourgeoisie. And yet, a general strike? It's easy to understand. In small workshops, in taverns, in bakeries, etc. The trade unions were increasingly organized, and in previous years and months they had demonstrated their ability to fight.

A few weeks before the uprising there was another important

general strike in Vitoria-Gasteiz, in this case to call for improvements in the working conditions: reduce the working day to 44 hours, leave the industries that are about to close in the hands of the workers, without a piece of work and without overtime, decent housing... All trade unions were involved in the strike, UGT, ELA-STV, CNT and even the Catholic Workers Union (SOC). At first a negotiating commission was set up with the Alavese employers, but the employers called for a strike when the petitions were ignored. “We know what the spirit of Gasteiz’s working class is,” he says in his statement, and we do not think it is necessary to say that we have to fight.”

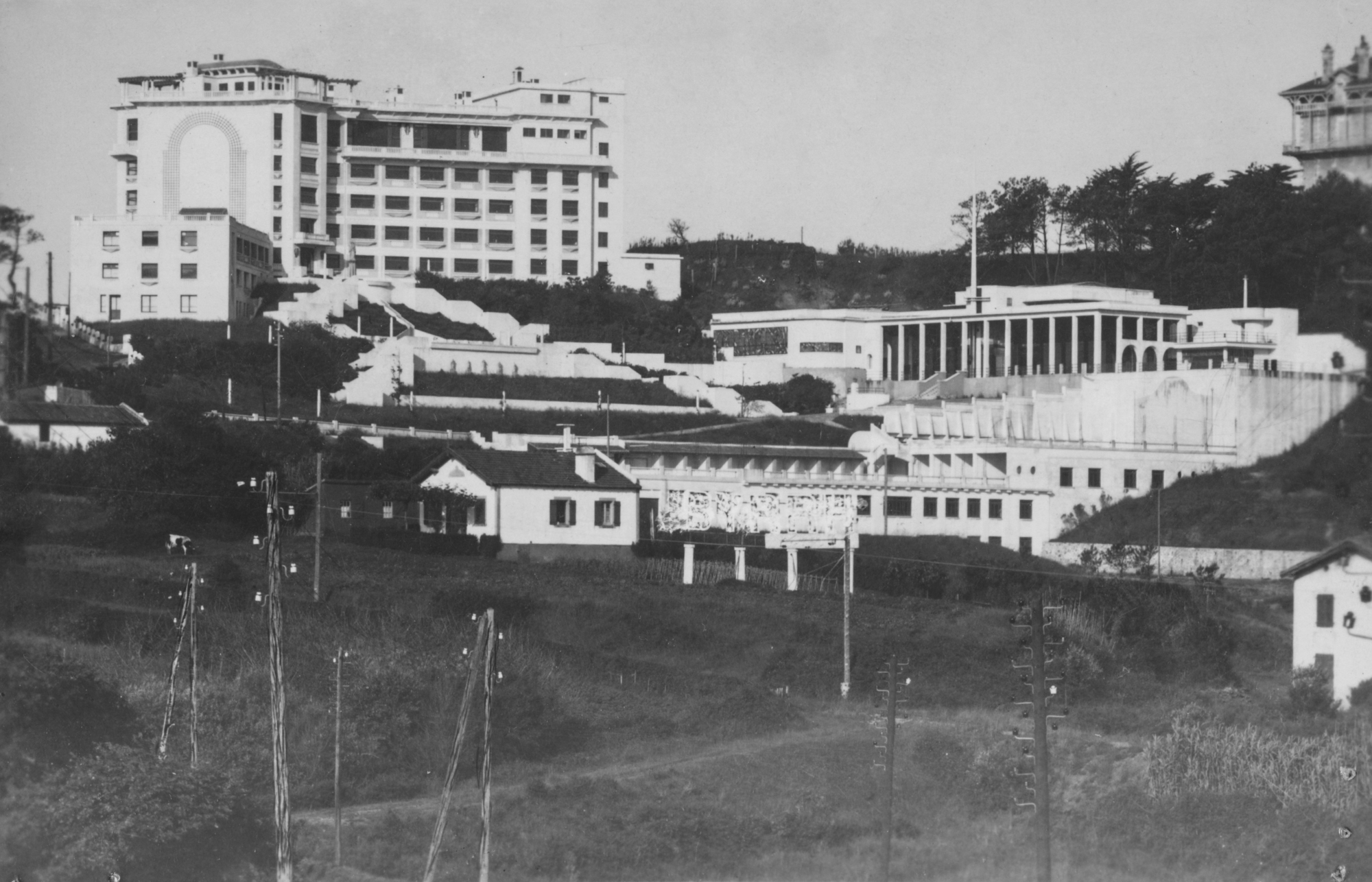

On 25 May the city woke up completely immobile: “It is undoubtedly the broadest, strongest and longest lasting unanimous strike in Vitoria-Gasteiz,” said the acting Republican photographer and mayor Tomás Alfaro. Throughout the week there were demonstrations and clashes, breaking some glass of shops, queues to get basic food... The Government sent a delegate to agree a solution with the strike committee and on 29 May more than 3,000 workers met in the assembly at the Vitorian Fronton. The following day an agreement was reached, with a wide range of demands, which included a total of 44 hours.

In Vitoria-Gasteiz there were hardly any factories. Like Pamplona, it could be thought that it was the capital of a “new Covadonga”. And yet, a general strike? It is easy to understand: trade unions were increasingly organised in workshops, lodgings, bakeries, etc. of the city and they had already demonstrated their ability to fight

In the most industrialized areas of Euskal Herria, in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, there was not so much mobilization during these months, but more “quiet” in Vitoria-Gasteiz. Why? Supporters of the left-wing government and conservatives believe that this strike was “out of place” and that it should be linked to the environment that lived in Spain – at the very time when conflicting strikes took place in Vigo, Valladolid and Barcelona.

Political tension throughout the state had skyrocketed over the past two years. In 1933 the massacre of the Old Houses – 18 murdered – became a symbol of savage repression against workers, and the oppression after the October 1934 revolution was no less important. In several history books it can be read that in Vitoria-Gasteiz that insurrection was “very deficient”. But then, how do you understand that during the hostilities you can buy bread only in one place in the city? Why did the UGT and ELA-STV premises close? A total of 37 people were arrested in the capital on charges of manufacturing explosives in some cases.

For many, the 1934 repression was a kind of essay of what would come two years later in the war. The military had long been determined to resolve the social issue: Like with the Moors of Arrife. Thus, the conspiracies multiplied as the summer of 1936 arrived, the maneuvers of the requetés and the smuggling of weapons intensified.

On several occasions in Álava Republicana was denounced by a medical captain at the headquarters of Vitoria-Gasteiz, Luis Sánchez Capuchino, and by the commander of the Flanders Regiment, Ramón Saleta, who filtered information. At the time of the coup a military case was opened against the newspaper’s director, Antonio García Lorencés, for the leaks that occurred. But once fascism was defeated, they did not need any court to kill him, on 22 November he was taken out of prison and shot.

The Alavese military command, General Camilo Alonso Vega, was up to the teeth in organizing the uprising, by hand with the traditionalist cacique José Luis Oriol, the largest in the area. However, until the last moment they had doubted that the garrison would join several regimes, such as the artillery, where there were a large number of Asturian CNT soldiers. When the day and time came, as always, the top ones played poker with the lives of the bottom ones.

Uplifting versus general strike

The uprising generated very different situations in Hego Euskal Herria. Navarre became the main epicenter of the rebels of the State since the time when thousands of requetés took the Plaza del Castillo de Pamplona. In Bizkaia, the military clearly opted for the republic. In Donostia-San Sebastian, the people at the Loiola barracks did not pass by. Those on the left, for their part, after occupying the headquarters of the assaults and acquiring the weapons, called a general strike on 18 July. This sequence was decisive for organizing the defense of the Gipuzkoan capital: both in the neighborhood of Larramendi Street and in the attack on the Hotel Maria Cristina, militia men and women showed enormous courage.

In Vitoria it happened backwards, the military clashed. On the day of the uprising, Dato Street was a murmur. There was some altercation at the headquarters of the Alavesa Brotherhood where the Carlists met and the Republicans asked the then civil governor Navarro Vives to close the premises and deliver the weapons. Even the commander of the Civil Guard offered to help. Hundreds of people gathered in Florida Park yelling “we want to fight, close the way to the fascists, long live the republic!”

José Luis Lonbana, lawyer and member of Eusko Gaztedi, left José Miguel Barandiaran the testimony of what happened in Vitoria-Gasteiz, when he fled to Iparralde. He says that they were about to get 37,000 rifles that afternoon. “We were told that in the Civil Government a sergeant appeared with the keys of the artillery park in his hand.” But the governor did nothing; he stopped in office and got permission from the military to go to Bilbao, perhaps as a reward for his submissive stance. Within a few hours, the military proclaimed the "state of war" in which they are found.

From there began the first arrests and several premises were closed, including those of Eusko Gaztedi, UGT and the Republican Circle, whose slate could still be read in the demonstration called for on July 19 in defense of legality. It was never done.

On 23 July, the new governor opened the camp, remembering that workers who did not return to work would be terminated. The first shot was a baker who didn't go to work.

On Monday, 20 July, general strike at the CAV and Navarra. With newspaper rotations closed, the Ajuria factory has hardly any staff, no milk or bread and few open positions. This panorama and the coldness of the Gasteiztars made the authorities up nervous. A campaign of disinformation and threats was immediately launched. The reactionary newspaper El Pensalavés issued a false note on behalf of UGT and CNT in which the citizens were asked to return to work; even false bars appeared on the street with the same objective. However, the strike lasted for at least another three days.

On 23 July, the new governor opened the camp by recalling that workers who did not return to work would be terminated from the contract: “The bosses will send me in the next 12 hours a list with the names of the workers dismissed in their industries, workshops and works.”

By then, however, many people had gone through Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, drawing the front, the repressive monster from the rear was underway. The first shot was a striker baker who didn't go to work on day 20.

1936-1976-2016 The

Fascists dissipate the initial positions with black lists, cleanings and rifle blows. In Vitoria-Gasteiz prison, the number of prisoners increased fourfold in just a few days. On July 25, Santiago Day, at the Falangists' headquarters several women were beheaded and forced to drink rabbit oil.

Mass firing began in August, as the “enthusiasm” of the people was too warm. The authorities had notified: “Especially in the whole of Álava and in Vitoria-Gasteiz,” if anyone dared to do “the smallest nonsense,” in the defeat of the hostages who were in their hands. The five mountaineers detained on 14 August on Mount Gorbea were murdered and in the coming weeks the shooting has increased, especially since the propaganda officer of the Millan Astray movement visited the city.

Anarchist Columba Fernández was also murdered in those days, after leaving the prison of women who were on Fueros Street, where several dozen women were harassed and persecuted for several months. Fernandez was known for having fought on the front lines in the workers’ movement in Vitoria-Gasteiz and they did not forgive him. The President of the Council, Teodoro Olarte, and the Mayor of Vitoria-Gasteiz, Teodoro González de Zarate, also had the same fate, as other 300 people from Álava.

“It seems that the ice of antipathy has begun to break among the workers,” Thought Alavés said with joy at the end of that bloody summer. They would never think that 40 years later the assembly would be stronger than ever in the new neighborhoods of Vitoria-Gasteiz and that their heirs would once again stain the sidewalks of the city with the blood of the workers on March 3, 1976. Sign that the quiet city has white skin but red veins.

Prentsaren bilakaera 1936ko altxamenduak Gasteizen izandako gorabeheren isla izan zen; errotatiba guztiak geldi egon ziren lehen egunetan. Álava Republlicana ez zen kalera irten uztailaren 18aren ondoren eta bere zuzendaria fusilatu egin zuten hilabete batzuk geroago. El Pensamiento Alavés Jose Luis Oriol karlistaren esku zegoen, uztailaren 22an berragertu zen mugimendu faxistaren bozgarailu lanak eginez. La Libertad egunkari liberalak hainbat hilabetez iraun zuen, eta harrigarriro, altxamendua izan eta egun batzuetara oraindik Errepublikaren eta demokraziaren aldeko testuak publikatu zituen.

Iazko uztailean, ARGIAren 2.880. zenbakiko orrialdeotan genuen Bego Ariznabarreta Orbea. Bere aitaren gudaritzaz ari zen, eta 1936ko Gerra Zibilean lagun egindako Aking Chan, Xangai brigadista txinatarraz ere mintzatu zitzaigun. Oraindik orain, berriz, Gasteizen hartu ditu... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

1936ko Gerran milaka haurrek Euskal Herria utzi behar izan zuten faxisten bonbetatik ihes egiteko. Frantzia, Katalunia, Belgika, Erresuma Batua, Sobietar Batasuna eta Amerikako herrialdeetara joandako horien historia jasotzeko zeregin erraldoiari ekin dio Intxorta 1937... [+]

Ezpatak, labanak, kaskoak, fusilak, pistolak, kanoiak, munizioak, lehergailuak, uniformeak, armadurak, ezkutuak, babesak, zaldunak, hegazkinak eta tankeak. Han eta hemen, bada jende klase bat historia militarrarekin liluratuta dagoena. Gehien-gehienak, historia-zaleak izaten... [+]

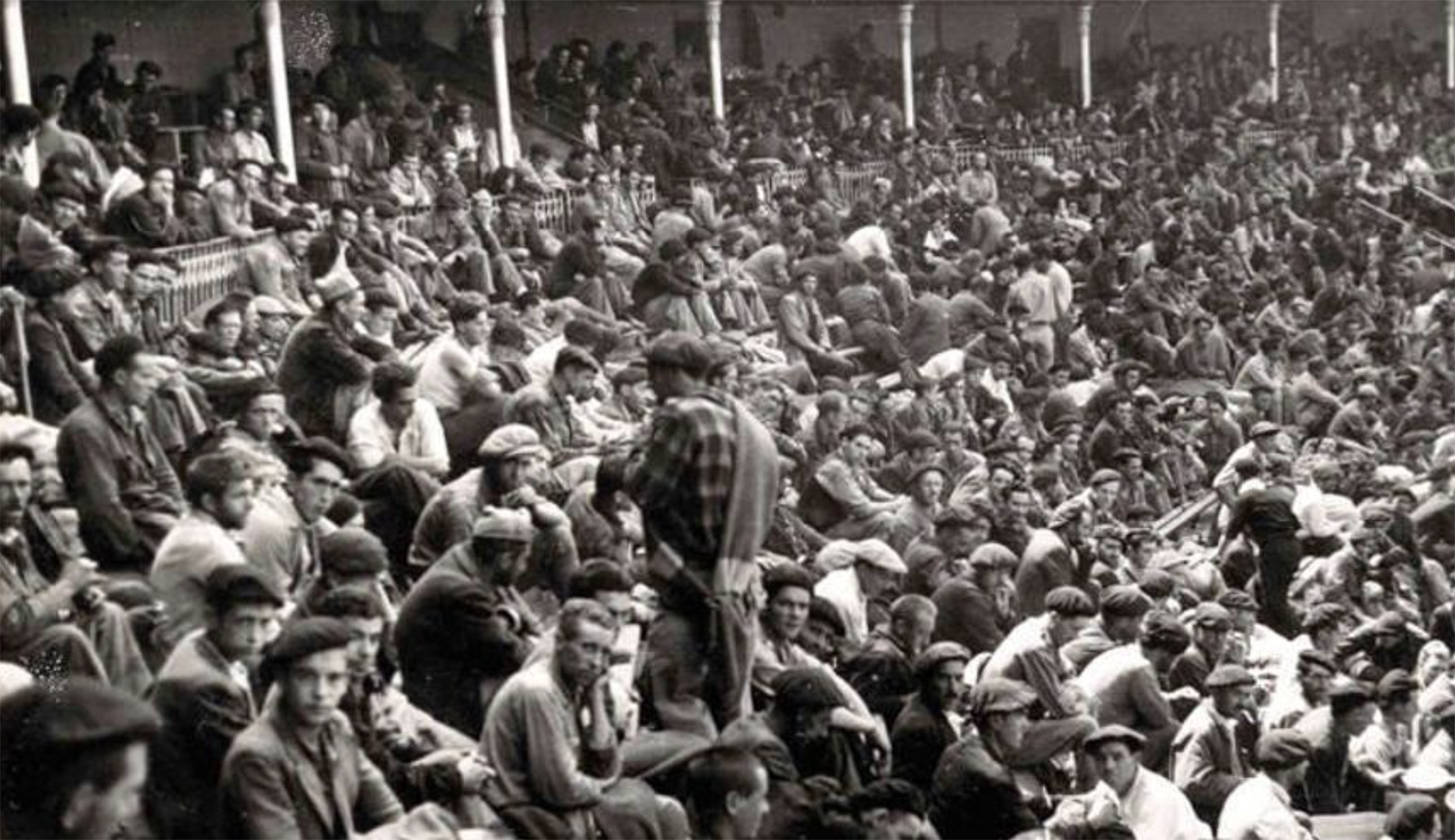

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]