"The riots don't invent on paper, they're chased: fighting you know how to fight."

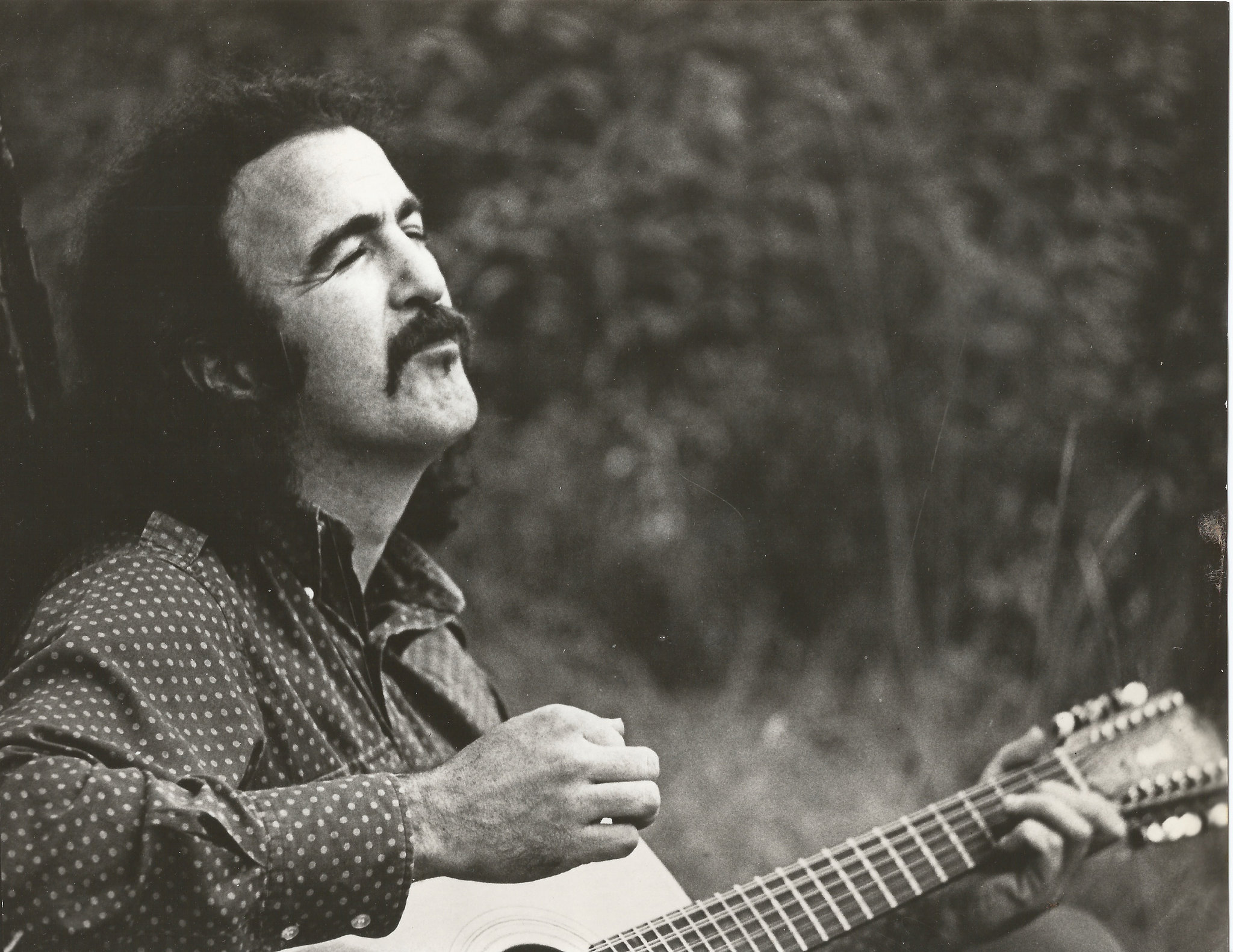

- The Italian writer Nanni Balestrini likes to experiment. Born in Milan in 1935, poet, novelist and long-standing essayist, these are not the only experiments he likes in the letters: his fiction is probably the most vivid chronicle of the innovative Italian revolutionary movements of the second half of the last century. We have had the opportunity to chat with him at the Book Fair and the Radical Literal Ideas of Barcelona.

“Forty thousand defendants, more than fifteen thousand prisoners, six thousand condemned … Behind these numbers are the ‘special jails’, torture, isolation, the best of the two generations for silence.” This summary summarized the “excellent operation in defense of the Italian ‘democracy’, L’orda d’oro (1968-1977) written together with Primo Moroni. The great ondata rivoluzionaria in the essay and creative, politics ed esistenziale. What remains of those years in Italian democracy today? Who has taken the witness?

More needs to be added to this long list: In the late 1970s, with the great repression that led to the end of the “70’s movement,” many of his colleagues committed suicide, as they found it impossible for that beautiful era to have an end and something much worse. Today it seems incredible, but there were many suicides, especially among the youngest, among those who lived the so-called “77’s movement.” It was a generation different from the one that already existed at the University of 68, who were about 76-77 years old, 15-16 years old, suddenly discovered a new way of life perfect for the young, and lived with great happiness, with the joy of doing things together, with the joy of living together and of doing everything collectively. Everything ended from morning to night, but those young people believed that life looked like this. When all of this was suddenly taken away from them, despair came. But more things happened. Many others tried to forget everything, to look for the substitutes of that despair, and they embarked on the heroin path, which had undoubtedly spread all over the place. Two generations were lost, disappeared from life and from the Italian world: the people involved in the movement, the people fighting, the fastest and daring people, the people who had the most imagination... It was terrible, terrible, and Italy is still unable to raise its head since then, mired in shit, unable to regain its citizenship. No generation has emerged capable of revitalizing that political and social action of the time.

No one took the witness?

This is a complicated question that needs to be addressed from two perspectives: on the one hand, we have to take into account the special context in which the struggles of the 1970s took place. All of this happened after 1968, when he fought against authoritarianism and for liberation. Then there were all kinds of achievements, feminism emerged, the family model was questioned, the relations between women and men were questioned… and the modern life we live today was consolidated. You can't imagine what things were like before 1968, how young people lived, how families lived… Everything was totally different. This change came about, therefore, and that was the first part of those years. On the other hand, there was a difference more directly linked to politics, which had to do with workers’ struggles, but that has nothing to do with what we have today, because then it was a totally different world: the world of production, the world of industry, and all that has changed radically, factories have gone, there is no working class of then, etc., and therefore, to think that the same things can be done today is wrong and even dangerous. However, we can take into account the teachings of those years. There are times in history where there is a possibility of rebellion, and then it is just and appropriate to insurrect. In history, they have happened. There was the French Revolution, the Bolshevik Revolution… The Italian Revolution of 1970 was not a great revolution, but an attempt to revolt, which took place at a certain time and which had a great youthful participation. It must be taken up again, but not with the same content or in the same way, as things have changed altogether. New ways must be found, therefore, in those old myths… I remember how in the 1970s there were many groups, political groups of all kinds, there are Maoist groups who believed that what Mao did in China had to be done, but that does not make sense. Others thought that we had to make a revolution like that of Russia, that we had to do that… No. Each era has its own characteristics, its peculiar forms, and it must be struck by what reality is, not according to what historical fantasy dictates us.

“To think that today you can do the same things that in the 1970s is wrong. But we can take into account the teachings of those years.”

Gli invisibilin (Invisibilin) talks about breaking silence: “talks about what has been said about so many things and finally talks.” However, the book ends without interlocutors with these words of the protagonist: “It’s impossible that only the immense cemetery in which you find yourself is out, you hear me, I don’t hear anything anymore.” Have we recovered from “nothing”? Is there anyone on the other side who wants to fight against this immense graveyard?

He says it because he's in jail, and he wants to communicate with the outside, and it's obviously impossible, but it can also be the picture of what's happening today. So I wondered. Is there any possibility of communication? The answer is in your hands. Each of us and we do. Because the answers do not come by themselves, as by themselves, but from making politics, in a social and collective sense. We need an initiative that starts from subjectivity and responds to the situations that surround us. We can't wait for some voices to be called. It is we who have to leave in search of others who join our struggles.

The violence illustrates the delicacy of the violence of bourgeois democracy: the normality of exploitation, destruction and death, an essential condition of capitalism, faced with revolutionary violence. How do you see the current phase of capitalism, in which, upon entering into crisis, the mask of pacifist hypocrisy has been removed and the instruments of war and neofascism have begun to be used?

Indeed, this book is based on the propaganda of capitalism and bourgeois power, on its illustrated violence, since all the texts of the book are based on the things that are read in the newspapers. I tried to question those texts, decompose them, make them understand that everything they say is false and that they put things in a specific area, in order to give another meaning. It is a violence against information, a kind of tension in the construction and manipulation of public opinion, an operation that eliminates the negative aspects of all that power does and shows only the good ones, although in themselves there are no such positive aspects. What is presented to us as a reading of what is happening in the world totally violates us through its violence. But things are different from what the media is telling us, the media is transforming reality to subject us, trample us and become slaves.

“There are historic times when you can insurrect, and then it’s good and just to rebel.”

At Vogliamo tutto (We all want it) we are presented with a time of struggle in which everything was possible. After months of assault on the sky and fighting for everything, hoping to conquer the masters, “a beautiful reddish sun that rises on the horizon” ends the story that leads us to one of the simplest and most demanding descriptions of the violence that wage work brings with it. What can be done today to put at the centre of our struggles the abolition of wage slavery?

The sun that appears smiling… That reference of the sun is somewhat ironic, because the communist literature of that time talked about the sun of the future, and that is why the sun of the future appears. The character talks about that sun. It's a little autistic because it says. “Well, we have fought the police, we have made this strike and this fight, etc., and now it is, now we are in another phase, then we will see...”

Today you don't have to ask him or me, because I'm not a political theorist, I've written my books always after things have happened, it's not that I've written the books first, and then people have dared to do things. I wish I could do that! Better still, tell me what to do and I'll write you a book. I'm here, waiting!

As I said before, the situation has changed radically, it is totally different, the current work is not in the factories, we have automation, there are machines, computers, all kinds of devices that limit time and people, that remove the limits of the time when working and outside time differed. People are every day, every hour is immersed in this productive cycle… and something needs to be done, yes, but starting from collective knowledge, not from a great theorist. Until Marx did not invent the way to win the fights by himself, described the fights, made a description of them, but did not say what needs to be done in each situation. And these things don’t get invented on paper, but they do it hard: you know how to fight fighting; it’s not the manual first and then “if it is, let’s do that”… It doesn’t happen as with the theater books, you have the text and then you interpret that text. At least I see it like this, then there can be the theorists, the philosophers, to give good instructions and… But things arise from collective action, when the masses see that something needs to be done and start inventing things, thanks to the large collective brain that invents the struggles. This was the case in the battles of Vogliamo, which took place every day.

It is significant that most of his characters do not have a special name, as they incarnate a collective subject, in the time of the sublimation of the individual self. In which collective subjects do you currently feel? And who is he going and where does he write his work?

This is a difficult thing to answer. I feel part of the collective subject of writers, because I, as a writer, mostly write; I write what I want, I have the freedom to write what I want: I could write love stories or write a novel about labor struggles, and I have chosen the latter, but I do it as a writer, not as a worker. And it's funny that, after I've published a book in the first person, I've been met by pretty innocent people who have told me. “It had to be hard when you were working at Fiat.” “No, look, I’ve never been a Fiat worker.” And with Gli invisibili, they said, “It had to be tough when you were in jail.” “Beware, because I have never been in jail.” But that's normal, because with all the novels written in the first person, people always think they're autobiographical.

“I could write love stories or write a novel about labor struggles, and I chose the latter, but I do it as a writer, not as a worker.”

But now we were not talking about autobiography, but about the political coalition, and I have my own political coalition, of course, I am a communist, but when I write a book, I don't write as a communist, but as a writer, about communist arguments.

Another distinguishing feature of your work is the way you play with language, how you twist it, how inexpressible to present it and represent it, to establish a rupture with a language that configures a coercive ideology. At the beginning of the paragraph, you do it with lower-case letters and non-comma. Why?

By default I use two styles. Violenza illustrata is largely based on the language of the media, especially in the language of newspapers, and also on television, in any case in the language of the mass media. And what I do is take that language and crush it, break it, divide it into lots of small portions and mix those parts together to, in my opinion, show the negative part that those texts hide: that's one of the systems that I use. In other books, like Vogliamo Tutton or Gli invisible, there's a voice, and the characters don't have a name or a psychology, because they're collective characters. Vogliamo, for example, is a Fiat worker, and it has the same psychological reactions and behaviors as a thousand other Fiat workers, more than ten thousand workers, have created in Tudela. The Gli invisibili is a general character: He is a political militant from the 1970s, with the same characteristics as the other militants; therefore, he is not a specific character, as in the traditional novels, with his individual characters and surnames, his parents, his children, his love story and his particular world. No, here's another character, a character we might call epic, like the symbolic characters of the ancient epic stories.

In his last novel, Sandoka, speaks of the Mafia and presents it as an inseparable part of the Italian State: not as a technical anomaly or defect of the system, not as a contingent issue, but as a characteristic of that State. To what extent are things like this today and how has the functioning of the Mafia been adapted to the present stage of capitalism?

That's Italy. In any case, I would say that capitalism has always had a criminal tendency, but, out of prudence, it has tried to respect the law. Large companies always try to manipulate balances, paying less to workers, but they have to be careful, because there are the laws, the courts … willing to intervene, and that is why they always go in close line between compliance with the law and non-compliance. In the case of criminal organisations, things are done illegally or in secret, and although the mafia bosses have to appear as respectable people, then they murder, steal and do everything. In any case, I do not see any great differences between them: there is a system that brings together almost all people’s activities and incomes, which all works as the Mafia wants. But unlike what happened in the 1970s, today there is no such form of collective rebellion. Today, if you want to escape from this system, there is only the solution of the individual revolt, that of leaving, that of going somewhere else. This is the conclusion of that cycle: In 1968 everything was positive, in the 1970s everything was perfect, then everything was destroyed and everything became a great desert.

The last question, to end, are you writing something now?

No, no, because I can't write about empty things, about what doesn't exist. I'm waiting. But I don't believe -- I would like. But that's what we all want, right? We all want it. We all want everything. And we are waiting for you to do so, because it is young people who have to do things. I will come to see something, perhaps, if you are running… But, hurry! I am eighty years old and I don’t have much time...

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

Aste honetan aurkeztu da Joseph Brodskyk idatzitako Ur marka. Veneziari buruzko saiakera. Rikardo Arregi Diaz de Herediak itzuli eta Katakrak argitaletxeak publikatu du poeta errusiar atzerriratuari euskarara itzuli zaion lehen liburua.

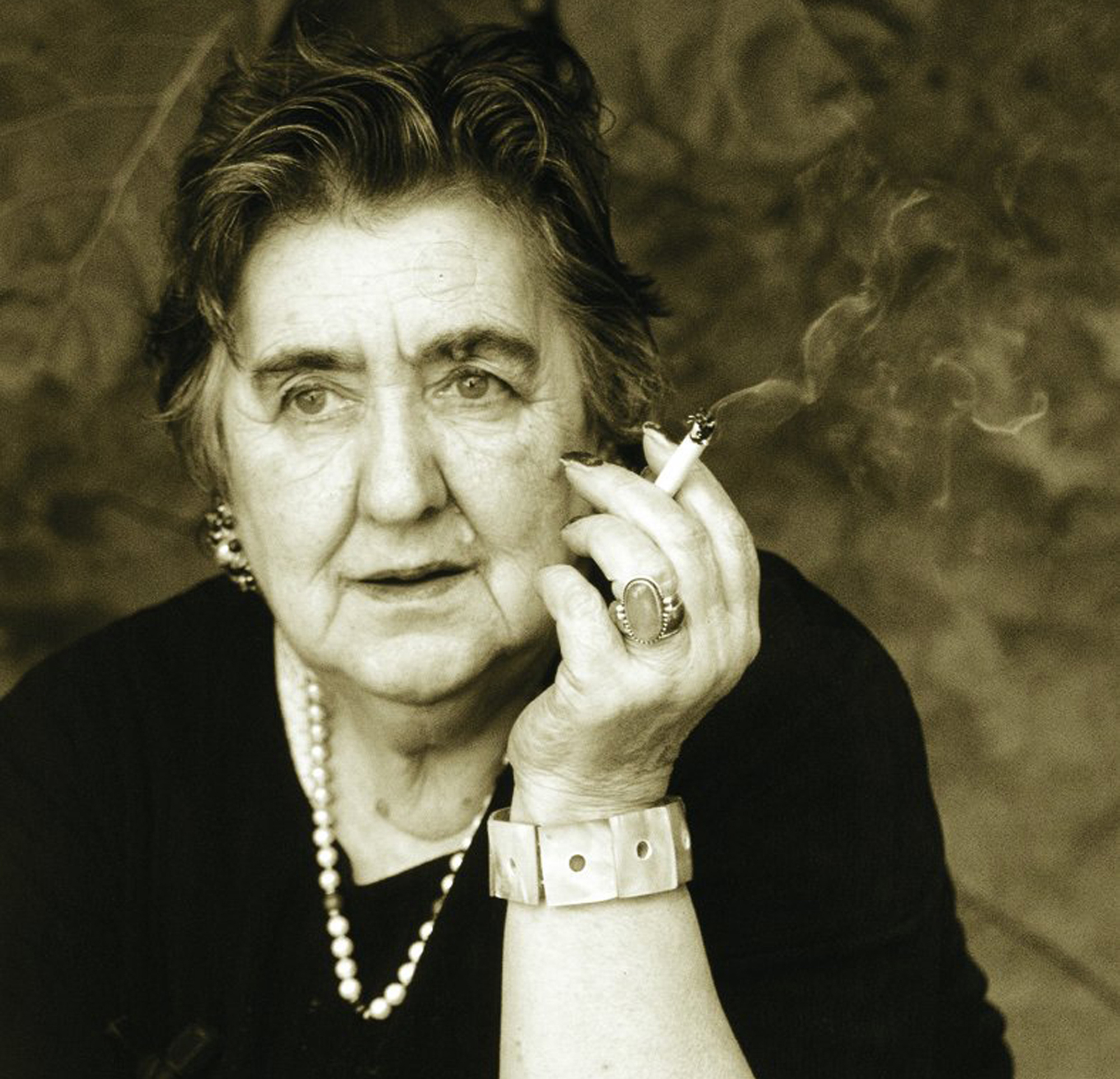

"There were women, there they were, I met them, but their families locked them in the mental hospital, put them in electroshock. In the 1950s, if you were a man, you could be a rebel, but if you were a woman, your family would lock you in. There were some cases, and I met them... [+]

Gauza garrantzitsua gertatu da astelehen honetan literatura euskaraz irakurtzea atsegin dutenentzat: W. G. Sebalden Austerlitz argitaratu du Igela argitaletxeak. Idoia Santamariak egindako itzulpenari esker, idazle alemaniarraren obrarik ezagunena nobedadeen artean aurkituko du... [+]

Asteazken honetan aurkeztuko dituzte Erein eta Igela argitaletxeek Literatura Unibertsala bildumako hiru lan berriak, tartean Maryse Condéren Bihotza negar eta irri (ene haurtzaroko istorio egiazkoak). Joxe Mari Berasategik euskaratua, idazle guadalupearraren obra... [+]

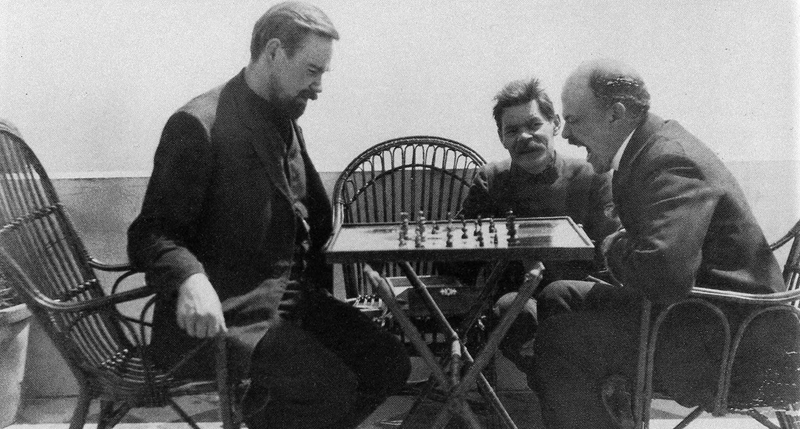

Wu Ming literatur kolektiboaren Proletkult (2018) “objektu narratibo” berriak sozialismoa eta zientzia fikzioa lotzen ditu, Sobiet Batasuneko zientzia fikzio klasikoaren aitzindari izan zen Izar gorria (1908) nobela eta haren egile Aleksandr Bogdanov boltxebikearen... [+]