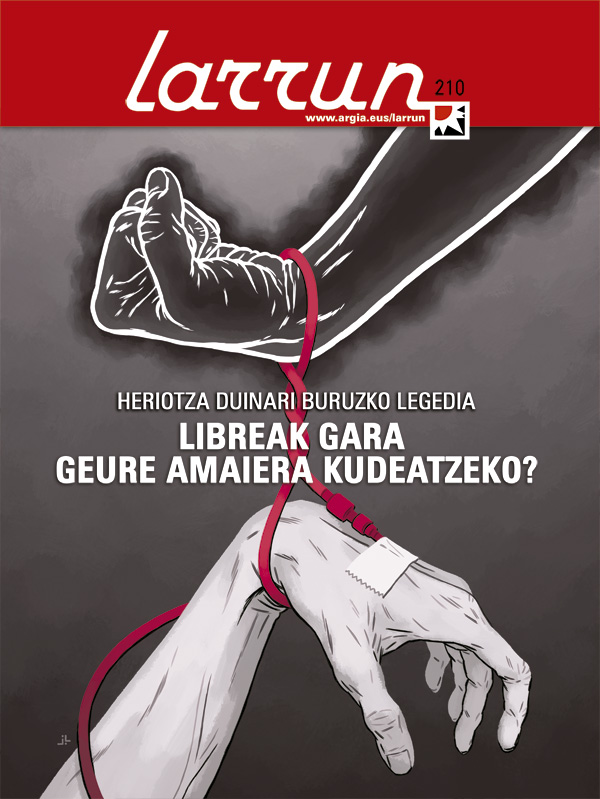

Are we free to manage our end?

- It is very likely that within a few days of the publication of this LARRUN, on 30 June, the Basque Parliament passed a new law on dignified death, the first of its kind to be in the CAV and the second of Hego Euskal Herria, which Navarra approved in 2011, although it has developed shortly afterwards. Both standards, such as the current law on patient autonomy in the Spanish State and that of the end of life recently approved in France, aim to guarantee the dignity of dying people, prioritizing their will on any other issue. In practice, however, these laws do not work, according to associations working for a dignified death. In his view, the rights of the dying will not be properly respected as long as the aspiration of those who are punished by euthanasia and assisted suicide, and who want to die freely, presents an obstacle to “medical fundamentalism”. Some are denied the right to go, while others are subject to unrecognised euthanasia, perhaps without them fully realizing themselves. We are going to work on the pages that come, with the help of several experts, the thorny road at the end of life.

Jacinto Batiz, Medikuntza eta kirurgian doktorea

Sestao, 1948. Bizkaiko Medikuen Elkargoko Deontologia Batzordeko presidentea. Zaintza aringarrietan aditua da, eta eremu horretan dabiltzan erakunde eta talde ugaritako kide edo aholkularia. Zaintza Aringarrien arloko burua da Santurtziko San Juan de Dios ospitalean.

Mabel Marijuan, Medikuntzan doktorea eta bioetika irakaslea EHUko Medikuntza eta Odontologia Fakultatean

Bilbo, 1960. Minaren tratamenduaren alderdi etikoei buruz egin zuen doktorego-tesia, eta EAEko Sorospenerako Etika Batzordeen sorreran parte hartu zuen. Duintasunez Hiltzeko Eskubidea elkarteko kide egin da berriki.

Iñaki Olaizola, Ingeniaritzan eta antropologian doktorea

Donostia, 1944. Heriotzaren inguruko gaiak ikertzen eman du azken hamarkada, eta lan horren emaitza dira bi liburu: Transformaciones en el proceso de morir: la eutanasia, una cuestión en debate en la sociedad vasca (Utriusque Vasconiae, 2012), eta Muerte, ritual funerario y luto en Euskal Herria (Utriusque Vasconiae, 2015).

Euthanasia and assisted suicide are prohibited by the legislation of the Basque Country. High, sedation allowed. The shortcut of death, according to some…

Jacinto Batiz: You don't need to use it with that intent. Sedation is a medical treatment that is used to reduce the patient's consciousness when the patient suffers a suffering that has not been repaired with other treatments. Sedation is neutral and we ethically turn it into good or bad, as intended. We can use it to decrease the patient's awareness, because it suffers a lot or badly, with excessive doses, it can cause death, and then it would be euthanasia sedation.

Iñaki Olaizola: There are two ways of thinking, one of which tries to distinguish sedation, assisted suicide and euthanasia as different categories, but I think the difference is small. It seems to me very artificial to separate sedation from euthanasia, considering it the first proper medical practice and rejecting the second. In fact, by simplifying a little, one could say that the difference between the two is the discourse.

Sedation says: “It is not to help death, but to relieve pain, even though the patient will die as a result of the donation.” Euthanasia alters the discourse: “We will help this person who has asked us to die.” Sedation is done with very small doses and agony can be prolonged many hours, 12, 24, 2-3 days… The same drug, in larger doses, can cause death in a few minutes. I think it is not right to set categories according to the dose, the speed of the event and the discourse. The intention is always the same: to help death.

J. Batiz: I do not agree with Iñaki. The goal of sedation is to lower the knowledge, providing the minimum doses necessary for this, so that the patient does not suffer either physically or psychologically. And through euthanasia we seek the death of the patient, I think they are different. We can cause death with excessive doses and, on the contrary, with too small doses we would be wrong, extending the agony more than necessary. This difference in time depends not only on the intensity of the sedation, but often it is the will of the patient to be deeply asleep, but without deep sedation, as he wants to maintain some contact with his family.

Mabel Mariban: Palliative sedation is the medical indication. The doctor prescribes the treatment and the patient says: it hurts me. Well, more analgesia then. Or, "I can't breathe." More oxygen… The patient tells you what they have and you take steps. But there are refractory symptoms that are not eliminated with regular treatment. When the time comes, the doctor himself tells the patient that the only way to eliminate this symptom is to decrease knowledge. And the patient may or may not accept it, as the patient always has the right to refuse treatment. What's the difference with euthanasia, fundamental to me? Euthanasia can only be proposed by the patient. The only thing you can tell your doctor is to help you die. And the doctor here says: I can't do it, it's illegal.

J. Batiz: I totally agree. He has done the separation well, according to the applicant. Yes, if we treat all the symptoms with enough intensity and we have no choice but to put the neck with morphine to relieve pain, and that is why we cause death, this is not an indirect euthanasia, as previously said, but a double effect. Our mission is, in one way or another, to relieve pain. And if that's why he dies first, nothing happens. We will not therefore think that we have carried out any euthanasia.

Iñaki Olaizola: "I think it is very artificial to separate sedation from euthanasia, considering it the first proper medical practice and rejecting the second. Simplifying a little, it could be said that the difference between the two is the discourse"

However, sometimes, what we consider to be a refractory symptom is only a difficult symptom, which we have not been able to solve, so before making the decision to use sedation we must ask the doctor next door for help. But if we cannot relieve the symptom, we must go to sedation, whatever the effect. And if that's why it ends before, it's over. On the other hand, I believe that healthcare professionals have learned not to give automatic responses when a patient asks us for euthanasia: “I’m against it and I’m not going to do it”, “I’m in favor and I’m going to do it”… First of all we have to work with that patient, because it’s very likely that behind that request there is a concrete situation that, if explained, we can help solve it in another way.

Do we die properly?

I. Olaizola: As a result of the fieldwork I have done on these issues, I have the impression that the quality of death in the Basque Country is poor. We live well in our society, but unfortunately, we die badly. And I think one step towards improving the quality of death would be to ask people, rather than leave them alone in the hands of professionals. I've asked a lot of people what has been the most prominent feature of the last death that has touched them closely, and in almost every case I've been told that the last days of the deceased had been useless. Two days, five, ten, in some cases a month… And in many of these cases, a conflict has arisen between respect for the will of the person in that trance – which I believe is the most sacred part in this debate – and the power that has been given to doctors.

I believe that in our hospitals, in general, the will and autonomy of the patient is not taken into account, it tends to be treated as if it were a minor. And the doctor's professional opinion is ahead of people's real will. Many people – and this is a relatively new phenomenon – do not want to be a burden on others, and the time we have a person under sedation – 20 hours, 30 hours, three days – is pointless suffering for the family. We have to obey who is in this situation and there is no reason for any profession to say “no, the time has not yet come”. We should all learn to respect the patient's will. I also know that, in some conflicts between terminally ill people and medical professionals, the problem is that euthanasia is a crime. I know we have a legal barrier, and that's why I'd like to overcome it. In this sense, I believe that the bill of dignified death that is being developed in the CAV will not solve anything. It is not new with respect to Law 41/2002 on Patient Autonomy [Spain].

It has become clear that Iñaki has a critical attitude to this bill, and I know that Mabel also believes it in the same way. What do you think, Jacinto?

J. Batiz: Similar. There can be no more attitude towards such a bill, because we have realised that those who are doing so know very little about the situation of those people who want to help. I agree with Iñaki, who no longer brings novelties to what the law of autonomy says. But I don't agree on anything else: I don't think doctors have empowered us so much, nor do we reject patients' autonomy. Those of us who work to reconcile ethics with medical activity, strive to disseminate strongly that autonomy must be absolutely respected, we cannot be paternalistic as before. The patient should decide, after being informed, that all cards are on the table.

However, I have to say that sedation is a right, but when the doctor considers it appropriate. Sedation is a medical indication. And you, Iñaki, mentioned the suffering of the family. But the suffering of the family cannot be a reason to force me to do something that may be contrary to the sick. Because there are siblings who believe one thing and others than another. Why should we heed them? Always to the patient. Yeah, I know you're going to say, “However, the family will suffer.” Okay, but that's what doctors can do at the time. And other things, today, no. When euthanasia and assisted suicide are decriminalized, we will have other instruments; those we want to use will be used, and those we do not want will not use them, we will also have the right to express conscientious objection. I have said publicly that the important thing is to universalize health care for those at the end of their lives. And if citizens, having the opportunity, don't want that, certainly politicians, or society, will have to look at the possibility of euthanasia.

M. Maritan: Let me tell the truth of Pernando: we live in an aging society and are increasingly aware of our mortality. In view of this, we ask ourselves, “how should it be?” But we must not forget that what has been called medical paternalism comes from a tradition of great importance. Communication between the doctor and the patient, bioethics, talking about palliative care… all of this has come to medical studies with the Bologna Plan, the first generation has still come out of the oven. Before that, no one has taught doctors how to develop their relationship with the patient; being a doctor does not teach you how to treat the patient well or manage your severity. That is not what is usually spoken about: the anguish of death takes everything to the fore, because it reminds us that we are all mortal. Therefore, the behavior of doctors, nurses, families, patients themselves will depend, among other things, on the maturity of society. And our society, Western society, is very immature.

Jacinto Batiz: "The important thing is that health care is universally available to those at the end of their lives. And if citizens, having the opportunity, do not want that, surely politicians or society will have to study the possibility of euthanasia"

When I became interested in these issues, I came to the conclusion that we were committing cruel murders here. The patient does not realize that he is being taken from the middle. That was stated in the Remmelink report: we are carrying out euthanasia. At one point, someone, the family, perhaps the patient himself, says: please help us. And a doctor says, OK. This creates confusion. Tell him “sedation” if you want, but that’s euthanasia! What did the Dutch say? “This account is private, all right, but it needs to be regulated publicly.” Why should it be regulated? I would answer you: when I don't want anyone to leave. That is what is happening with us now. A distressed family meets with a concerned doctor and together decide to increase the dose. When I say “when you don’t want,” I mean “before you know whether or not you want.”

If I can agree with my doctor in time… Suppose I have just been diagnosed with dementia and I say: “When I’m so bad, let me die of pneumonia, don’t take care of me, just…” To reject the treatment, the autonomy of the patient, without problems. But think that we arrived at this situation without having talked about it before, and some along with the doctor saying “take care of pneumonia”, others “do not treat”, he also in the face of his mortality… At some point he will say: “It’s already!” And a Dutchman looking through the slice might say: “How are you! You say no to euthanasia and you just killed one person.” That's called murder by compassion, and it's better to regulate it, because sometimes it can be by piety, but other times you don't know why. So as far as the law is concerned, which is what we were talking about, I told you, when he appeared in Parliament to discuss the issue, that the law, if it is to be done, must be very clear. He has to explain very clearly the situations that can occur at the end of his life. If this is the case, euthanasia and the recognition of assisted suicide will not be a problem.

I. Olaizola: In this sense, I would say that in the Basque Country the quality of death is random. Where you die, what doctor touches you… What’s more, what disease you have.

M. Maritan: I would add another factor: the maturity with which the patient and his family address the issue.

I. Olaizola: The quality of death is not democratically distributed, the social and personal context influences. That's why it's important to make a living will. The living will must be fostered and it is not done properly here.

J. Batiz: I agree that none of the autonomic laws in the Spanish State will solve the problem, and it has been my task to review a couple. On the one hand, for something Mabel said: professionals have to get educated well, and no law guarantees that education. Again, I asked a chief of surgery to tell his younger colleagues that they had to stop doing unnecessary interventions, some things don't make sense when there's a diagnosed terminal illness. But operations are done. “Let’s keep going to the end”, “let’s see what it has”… That attitude is very human and we have to fight it, but the laws do not talk about it for the time being.

At the heart of the debate is the definition of suffering. Who should we do? And how do we measure?

J. Batiz: This can only be done by the patient. Suffering is very subjective.

M. Maritan: In medicine it is said: “If the patient says he has pain, then he has it.”

I. Olaizola: As you asked about suffering… A new concept is emerging: the meaning of life. In the traditional model of the killing process there was no question of whether a life made sense: everyone had, to the extent that they were given, gods or not. In a way, we could use our lives, but we weren't their real owners. Now, many people, depending on their quality of life, wonder about the meaning of life and decide that below a certain quality that meaning is lost and want to leave. They want someone to help them die. It is also true that when the time comes, we often get content with less. In any case, we must be aware that the idea of dignity is not the same for all people. And some don't want to suffer physical or intellectual impairment. There is not a single model, so we have to listen to those who are in that trance, I think the three of us have joined in that.

J. Batiz: In line with what Iñaki said, Nietzsche said something that has helped me a lot: who has a “why” of living suffers almost any “how”. We have to give people a reason, we have to look for the meaning of their lives.

We do not stop remembering the dying patient, but there have been those who have taken years to ask for help to die. Voluntary death is at the center of the debate.

I. Olaizola: At the very least, I find no convincing reason to deny the right to die, but I do know the arguments used for this. One of them is a slippery slope: once the right to die is recognized, increasingly uncertain cases should be accepted.

M. Maritan: That is, where we have to set the limit.

I. Olaizola: It is difficult to regulate this area, but the slippery slope cannot prevent us, at least, from trying, because it is a matter for all of us. We all have the right to die even when there are no diseases involved. A legal system cannot force anyone to live a life that they do not want. There are people who can't find meaning to their lives. I believe that they have the full right to receive help to die from society. In what name can we ban someone who dies whenever they want?

J. Batiz: But that right is recognized, insofar as suicide is not punished. Another thing is that there are other people who want to intervene to make this happen, that is where the issue is. Let me tell you one case: one of our patients came outside the Basque Country for sedation, because our team did not want to give it. He was a man who was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (AEA). She wasn't in her dying, but after reflecting on her future life, she asked us for sedation to say goodbye to others and end in 24 hours. We told him that we would help to alleviate his situation, but that we would never accept that demand.

I. Olaizola: So did he not have the right to do so?

J. Batiz: We are not talking about rights, we are talking about medical indications. Sedation is an indication and in this case it was not adequate. The patient asked us something else: End in 24 hours. It's not sedation.

M. Maritan: This was a clear demand for euthanasia.

Mabel Mariban: "The anguish of death takes everything to the fore, because it reminds us that we are all mortal. The behavior of doctors, of the family, of the patient will depend on the maturity of society. And our society, Western society, is very immature."

J. Batiz: So we couldn't. So let us talk about legalising euthanasia. In the Netherlands they did so and, interestingly, the number of euthanasia decreased and the number of sedations increased. Why? To physicians, compliance with all the conditions for performing euthanasia entails many more problems than prescribing sedation. No one should judge sedation. And once euthanasia is authorized, the indication can be performed calmly. In Spain, however, many euthanasia sedations are performed without anyone realizing it. The decriminalization of euthanasia stops producing euthanasia, as it is carried out by sedation. At least I think sedation is misplaced in some situations.

I. Olaizola: If someone diagnosed with AEA cannot request sedation, it is not enough to express their will. I ask you for an ethical judgment on this. How far should we go?

J. Batiz: We speak from a medical point of view, from a theoretical point of view. All clinical activities have protocols. The Guide Book on Disease Care AEA will not find that sedation is considered adequate outside the terminal situation.

I. Olaizola: So, a patient who has been unable to move for years, who has manifested his desire to die long and frequently and who has no mental health problems, shouldn't he have the right to a terminal clinical sedation?

J. Batiz: I do not think so.

M. Maritan: Unfortunately, when I say what I am going to say, it seems that everything else is not heard, but I will say it: I believe that euthanasia and assisted suicide should be decriminalised, of course. If we accept that each person has his own life project, the management of death must be within that project. And let it not be a desire that is expressed once, in youth, but when the moment approaches. Because it is true that people tolerate much more than they think, but sometimes the opposite happens: that the patient bears it much less than they think, and that nobody pays attention to it.

I can understand that someone decides that their life is exhausted, because they consider it unworthy, etc. But please, let it not be for the pain that can be cured, because it is alone, or… Let society guarantee that. I would not accept euthanasia if there were no palliative care. But if, with all this, there are citizens who decide to end up, let us not make ourselves leap across the bridge because other practices are prohibited. We included euthanasia and assisted suicide in the set of possibilities.

J. Batiz: Society must, first of all, assure all citizens that at the end of their lives they will be attended by well-trained professionals and, if all of them choose another way of rejecting and killing this type of care, such as euthanasia, decriminalization should be considered.

Eutanasia. Osasun langileek zuzenean gaixoaren heriotza eragitea, gaixoak bere borondatez, ondo informatuta eta bere buruaren jabe dela hala eskatuta. Ezin dira eutanasiatzat hartu ahalegin terapeutikoa murriztea eta sedazio aringarria, besteak beste.

Lagundutako suizidioa. Bizitzari amaiera ematea, horretarako behar diren baliabideak norbaitengandik jaso ostean. Baliabideok ematen dituena osasungintzako profesionala bada, “lagundutako suizidio medikua” esaten da.

Sedazioa. Konortea gutxitzea, nahita, gaixoak dituen sintomak beste inola arindu ezin direnean –sintoma errefraktario esaten zaie halakoei– haiek eragindako sufrimendua eragozte aldera. Sedazio terminal esaten zaio hiltzear dagoenaren kontzientzia sakon eta modu itzulezinean murrizteari.

Efektu bikoitza. Sufrimendua arintzeko erabiltzen diren tratamenduen ondorioz, heriotza azkartzea.

Tematze terapeutikoa. Hilzorian den gaixoaren heriotza saihesteko helburuarekin, neurri terapeutiko desegoki edota gehiegizkoak ezartzea. Mediku deontologiaren kontrako jarduera da. Haren ifrentzua ahalegin terapeutikoaren egokitzapena da: tratamendu bat ez abiatzea edo haren intentsitatea doitzea, gaixoaren bizi-diagnostikoa murritza denean.

EH Bilduk aurkeztu zuen ekainaren 30ean Eusko Legebiltzarreko osoko bilkuran eztabaidatuko den heriotza duinari buruzko lege proposamena. Eztabaidara eramango den testuaren azken bertsioa beste taldeekin adosteko lanean, bilera eta bilera artean solasalditxoa egin dugu Rebeka Ubera legebiltzarkidearekin.

“Gotzainak sina lezakeen egitasmoa bidali digu EH Bilduk” esanez hasten da LARRUN honetan Duintasunez Hiltzeko Eskubidea elkarteko Fernando Marínek idatzitako iritzi artikulua.

Hasierako testu hura proposatu genuenetik lan handia egin dugu astero-astero. Gure lehen helburua lege proiektua tramiterako aintzat hartzea zen, eta behin hori lortuta eztabaidaren elementu guztiak mahai gainean jartzea. EH Bilduren jarrera oso argia da: eutanasia, lagundutako suizidioa eta sedazio terminala despenalizatzearen alde gaude. Halaxe adierazi dugu, izan ere, guk geure lege proposamenari egindako zuzenketetan.

Zer helbururekin aurkeztu zenuten lege proiektua?

Hirurekin. Batetik, bizitzaren amaierari buruzko erabakiak egoera horretan dagoen pertsonak hartzea, eta ez geratzea medikuen pean. Bestetik, eutanasiari eta lagundutako suizidioari buruzko eztabaida irekitzea, eta lortu egin da. Hirugarren helburua zaintza aringarrien eremuan hobekuntzak eragitea zen. Orain gutxi aurkeztu du Osasun Sailak zaintza plan berria; argi dugu gure lege proposamenak bultzatuta egin dutela.

Legeak ez du berrikuntza handirik ekarriko, LARRUN honetan iritzia eman duten aditu guztien esanetan…

Legea beste bitarteko bat da, gure ustez. Balioko du osasun sistemak, arlo horretan ere, pertsonen zerbitzurako jardun dezan. Gaur egun, egokitzen zaizun profesionalaren araberakoa da bizitza amaierako prozesua. Lege proiektuan garbi zehazten da zer norabidetan jokatu beharko dute denek.

Espainiako Estatuan mediku asko uzkurrak izaten dira gaixo baten sedazioa agintzerakoan, Zigor Kodea urratzeko beldurrez. “Medikuak argi eduki behar du sedazioa indikazio bat dela”, dio Mabel Marijuanek, “eta aldamenean edukiko gaitu lankideak, ondo ari dela esaten eta lasaitzen; baina mediku batzuek ez dute argi izaten, eta badaezpada apur bat murrizten dute dosia. Zalantza sortzen zaie, indikazio hutsa dena errukizko hilketatzat har ote daitekeen. Argi izan behar lukete sedazioa indikazioa dela, transplante bat edo antibiotikoak hartzeko esatea bezala”.

Espainiako Zigor Kodeak ez du suizidioa zigortzen, bai ordea bere buruaz beste egin nahi duenari laguntzea. Honela dio heriotza duinaren arloan dabiltzan orok hain ongi ezagutzen duten 143. artikuluak, bigarren puntuan: “Nahitaezko ekintzen bidez pertsona bati bere buruaz beste egiteko laguntzen dionak bi eta bost urte bitarteko kartzela zigorra jasoko du”. Hirugarren puntuak dio zigorra sei eta hamar urte bitartekoa dela suizidak bere helburua betez gero. Medikuei zalantza eragiten diena, berriz, laugarren puntua da, terminoak aipatu gabe ere eutanasiaz eta lagundutako suizidio medikuaz ari dena. Zehazki, puntu horrek dio beste norbaiten heriotza eragin edo hura gertatzeko laguntzen duenak arestian aipatutako zigorraren bertsio leundua jasoko duela –baina zigorra, nolanahi– bere jokabidea hildakoaren eskari argi eta zuzen baten ondoriozkoa bada.

Arau horrek eragozten du gaiari buruzko eztabaida garbia, Mabel Marijuanen esanetan: “Mediku askorengan sedazioa agintzeko zalantzak sortzeaz gain, Zigor Kodearen erruz, kalitate eskaseko heriotzak ez dira azalera ateratzen”.

Autonomia erkidegoetako legeek ezin dute Zigor Kodeak ezarritako muga hori gainditu. Beste bide batzuk urratzerik bada, ordea. Hego Euskal Herriko legebiltzar biek mozio bana onartu zuten 2015ean, Espainiako Gobernuari eutanasia despenalizatzeko eskatzearen alde. Baina keinu politiko hutsetik harago joateko aukera ere badago: nahi balute, Iruñea eta Gasteizko legebiltzarrek eurek eraman lezakete eutanasia zigor kodetik ateratzeko lege-proposamena zuzenean Madrilgo Kongresura. Eusko Legebiltzarrari dagokionez behintzat baliteke datorren legegintzaldian halako ekimenen bat abiatzea, Rebeka Ubera EH Bilduko parlamentariak azaldu digunez. “Beste aukera da Madrilgo Kongresuaren taldeen bitartez aurkeztea”. Lehenbiziko urratsa Gasteizen heriotza duinari buruzko legea onartzea izango da, edozein kasutan.

Gertakariak igande egunsentian suertatu dira 5:00ak aldera Gasteizeko Mitika diskotekan. Hildako pertsona 31 urteko gizon bat da, eta lurraren kontra buruarekin hartutako kolpe baten ondorioz hil da, antza atezainak kolpe bat eman ostean.

These were my last words when we left, held hand in your deep breathing sleep. Your heart stayed forever without a special, simple, dignified pain. As you want and demand. How we want and respect.

Already a month before the arrival of winter, the last days of the longest night,... [+]

First of all, we wish to extend our condolences to the family and friends of the woman killed in early August.

The people of Gaintxurizketa are fed up with the disillusionment of the administration and those responsible.

Those of us who live in the neighborhood are forced to... [+]

Paris 1845. The Labortan economist and politician Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) wrote the satire Pétition des fabricants de chandelles (The Request of the Sailing). Fiercely opposed to protectionism, he ironistically stated that the sailing boats asked for protection against... [+]

(Azken aldi luzean ezin naiz gauez atera, eta arratsaldez ere larri, eta asteburuetan ere ez, eta (jarri zaizue jada ihes egiteko gogoa), marianitoak eta bazkari azkar samarrak izaten dira nire enkontruneak. Konpainiak ondoegi aukeratu behar ditut. Ezin ditut poteoak... [+]

.jpg)