The questions of an artist in the middle of a rally

- It is already difficult to imagine a political act without artists. Fleeing the usual rallies, in recent years all kinds of artists have been called to make their contribution at festivals in favour of or against some political message, in the eye of the public's excitement. But what context is an event for artistic practice? What risks does it have to look beforehand for the emotion of the listener? What is a committed artist? We have talked about these and other issues with Inés Osinaga and Hedoi Etxarte.

“Political acts often resemble the main Sunday Mass too much.” This is what Inés Osinaga says, who has not participated once or twice in these cases. The sensible comparison, one thinks, is, more or less, the places where the beliefs and beliefs of a community are strengthened. You can easily imagine: believers listen to the pulpit, follow the songs, the espiches and the instructions that come from there. Clap now, sing now, screaming now, getting excited now, and when we're done, getting up all of us and coming home, smiling, with a sense of relief, we already know who, we've forgotten a little bit before we enter here, but we've taken enough self-esteem to go with our heads up somewhere else. Still, most political acts remain places of identity self-affirmation in these places, if there was anything in them. And maybe that's it. In these times of the show, in the early days, other media, such as social networks or television debates, seem more appropriate to convince the majorities with political messages. However, it happens that, knowing that you are acting “for yours” in the acts, if you behave softly, without rethinking anything, reproducing the traditional imaginary, you run the risk of starting to lose some of the ones you already believed.

It seems that in recent years there is a formula that systematically occurs to the organizers, either for acts with few resources, or with large infrastructures: to invite artists of all kinds, mainly bertsolaris and musicians, but also poets, writers or dancers. Then the questions arise: What is the place of these artists in political events? Do they have full freedom to act for themselves or are they limited to exercising a predetermined function? At the very least, it seems that this context is not the most appropriate to create anything artistically interesting, if art is understood as an act in which principles, values or beliefs are questioned. So what are artists called for? What are you looking for in them?

Inés Osinaga:

“We have too many open fronts, and if it’s going to be brave to face them, we

can’t burn ourselves.”

Some people think that these are questions that have not reflected too much and that, without further ado, inertia has prevailed. Bertsolari Asier Azpiroz cited in an article entitled Bertso puppets that when chanting in some acts he has felt more, and that if he were not he would be the same or even better. “(Despite coinciding with the message of the event), throwing a pamphlet message with the melody and rhyme of a group, produced me a kind of chills through the spine,” Azpiroz said, while asking: “Is there a need for verses everywhere? Does it not seriously harm the verse itself?” The article urged the organizers to reflect on the subject for a minute. Osinaga thinks that something similar happens with musicians: “If in this town we put a mushroom in the village square, we do a song to it. It seems that we are convinced that songs have a certain ability to mobilize to spread that cause that we want to defend everyone, that everyone will know about it… And I suspect it’s not the other way around.”

Two years have passed since that article of Azpiroz, the act continues and artists are still called massively to give a little color to the rigid rallies of always, so that they do not have the rigid reasons of the microphone and adhere to the public in a more irrational way; in short, to put a component that seeks the listener's empathy: emotion. It's not a new account. Hedoi Etxarte recalls that emotion was one of the axes of the debates of the critical artistic production of the twentieth century. Stanislavski versus Brecht. “Do we change people’s minds for empathy or for reason? What frugality is born in one and what frugality is born in the other? If we don’t have empathy for someone because it’s not like us, aren’t we going to fight for him?”

“The yes to political acts has more political than artistic commitment”

But the previous search for emotion can be very dangerous artistically, as the activity that predominates on stage has more to do with the museum's culture than with creation. In short, anyone who wants to emote an entire community must necessarily turn to the references that that community shares, must use that heritage in a way that is effective and ends with one of the most serious mistakes that can be made: to create an artistically very conservative artifact to help a politically transformative message.

Artist and person

What happens to the artist's mind when he receives an invitation to participate in a political act? Etxarte, considered a follower of Lenin's school, conceives the artist as a screw and a revolution wheel, and then asks: “What contribution can I make to what those who are in this mobilisation have not done but who need it? How can we be as understandable as possible? Is there room to introduce aesthetic innovations that are not in that format without looking for prominence?” Osinaga, on the other hand, understands the person and the artist in two different planes. And, therefore, it distinguishes between the causes that protect them personally and those that protect them artistically. "A while ago I decided that I would be presented publicly in favor of some issues and not in favor of others. It's not that I don't leave, it's that I don't want to leave. In this town we have put t-shirts of different colors: orange, green, blue, purple… We have too many open fronts. And when we face them, if that face has value, we can't burn it."

Hedoi Etxarte:

“There’s a zombie scene related to punk rock and ska: it’s reactionary in musical forms, words and rituals.”

The rights of prisoners and feminism. These are two issues that Osinaga barely tells you no. It's been a long time since she decides to get wet by these issues and not by others. “In this case, the yes has more political than artistic commitment. What happens is that what we put in the window is that it is our artistic self, and many times that artistic self ends what it would never do, on behalf of that political self.” In addition, he recalled that in most cases he was called for anything other than singing: recording a video, reading a text, going out in the photo of the press conference without saying anything, wearing the t-shirt in the concert, saying a few words by the microphone in the middle of the concert… then, on one occasion, playing a song in the acts and, in the best cases, playing a song with the whole group. “I’ve always said it’s a microphone to tell us things and try to change them. But, over and over again, I feel like I wanted to be a musician.” He lives with great contradiction the clash between the musician and the person. “I thought that artistically I’ve paid dearly to have participated too much in these kinds of events, but I’ve done it because the interior has asked me for it. Because being a musician is one thing, and being a musician is another in the Basque Country. And even more: being a music woman is something else different in the Basque Country.”

Compromise edges

The new saying reads: “A committed artist begins to be an artist committed to a political act and ends up not being an artist or engaged.” It is not, of course, a serious statement, but it can serve to cast doubt on some of the assumptions. For example, why it is so reactionary, with exceptions, the musical scene that is now moving around major political acts. Etxarte mentions a trend: “There is a zombie scene related to the punk rock and the ska, which lives in the revival, and which is not just conservative, it is directly reactionary: in musical forms, in words and in ritual.” It may be because commitment is understood very strictly, especially when it comes to participation in events or to singing explicit slogans. However, there are some artists who otherwise bring politics to the ground: For example, Maialen Lujanbio in the Basque Country Irratia or Unai Iturriaga in Jakin. Or those who have performed their musical activity with a policy of deep sense: Like Broken Brothers Brass Band, “engaging the community, with sophisticated rhythms and harmonies, with acidic letters.” There are also those who, in their opinion, have politicized the means of production “like those of Bidehuts or Kerobias: through licenses and distributions”. Or the soundtrack and Think Tank as “Negu gorriak and Fermin Muguruza or La Polla Records”.

“Do we change people’s minds for empathy or for reason? What frugality emerges in one and what frugality in the other?”

Another possible reason to explain this conservative scene around the celebration is that many artists use these places to search for visibility. To some extent, the fact of appearing there serves them to settle in the plaza, to scream “here I am” and, by the way, to secure more places throughout the year. It is not a new paradox that people should be involved in acts in favour of collective causes in defence of their own interests. Osinaga has reflected a great deal on the subject: “How many of the concerts we do in the year are behind that have no banner? And what capacity do they have to mobilize? How many people can we reach musicians without any militant context?” And, after all: “Do political acts need artists or does the Basque Country scene need a banner behind it?”

The march and struggle are inseparable in these times.

We have known Aitor Bedia Hans, a singer of the Añube group for a long time. At that time we were reconciled with BEÑAT González, former guitarist of the Añube group. It was at the university time, when the two young people of Debagoiena came to Bilbao to study with music in... [+]

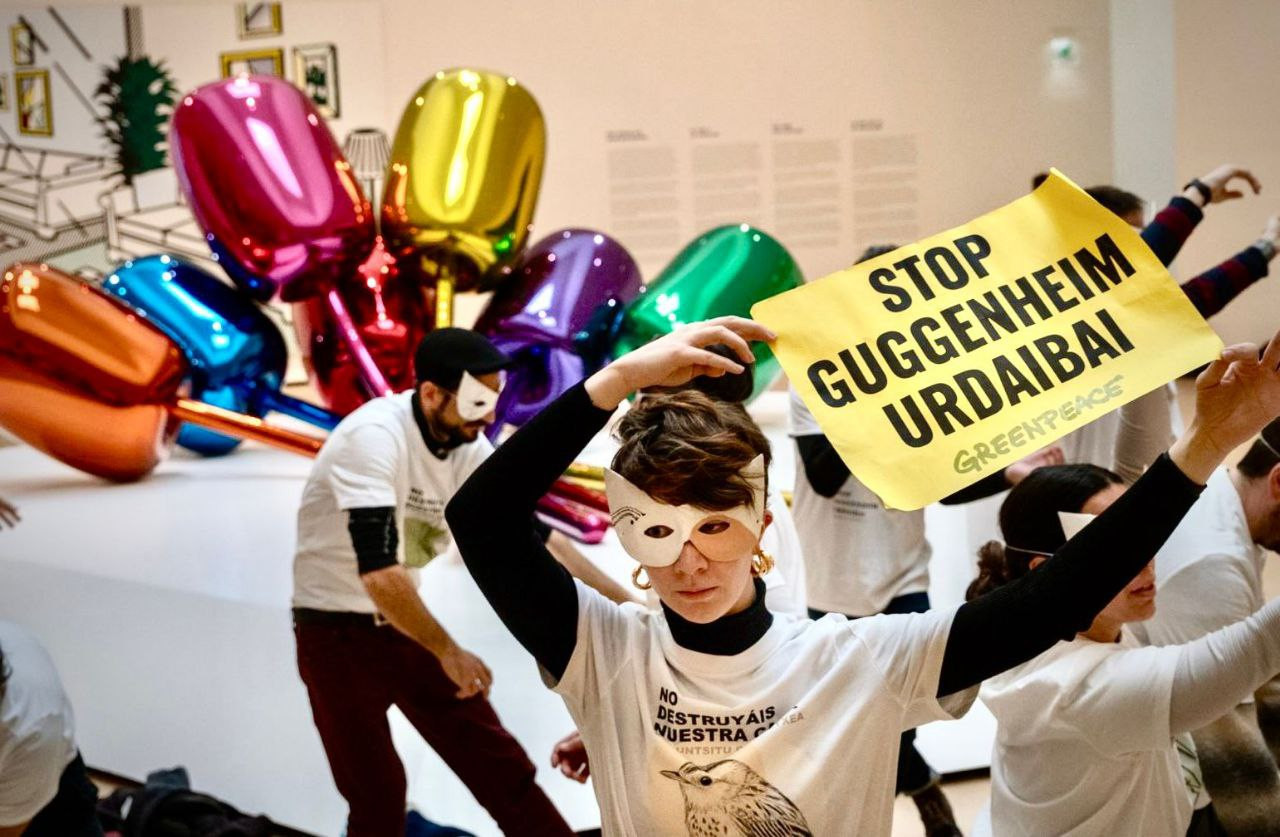

Two years ago Urdaibai Guggenheim Stop! Since the creation of the popular platform, Urdaibai is not for sale! We hear the chorus everywhere. On 19 October we met thousands of people in Gernika to reject this project and, in my opinion, there are three main reasons for opposing... [+]

With this article, the BDS movement wants to make a public boycott of the event to be held on 24 September at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. In it, they will have the presence of the renowned Zionist artist, Noa, who will present his last record work.

When, in the context of the... [+]

Mende batean, Baionako Euskal Museoak izan duen bilakaeraz erakusketa berezia sortu dute. Argazki, tindu edo objektuak ikusgai dira. 1924an William Boissel Bordaleko militarrak bultzatu zuen museoaren sorrera, "euskal herri tradizionalaren" ondarea babesteko... [+]