...and they continued to kill

- What was wanted to be sold as a fight between Carlists was the dirty war actually organised from state apparatuses. On 9 May 1976, we followed the trail of the mercenaries who participated in the Montejurra assault, as well as in the Franco regime, who also acted in the sewers of Democracy.

“This time we all know who has shot, wounded and killed in Montejurra. Navarre has just seen how the law of terror, with firearms, is applied against defenceless and unprotected citizenship.” Thus began the magazine Punto y Hora de Euskal Herria the editorial on the events of Montejurra, whose cover was marked with capital letters by the word “Impunity”. On the verge of forty years, impunity has not only lasted, but the dirty war has been a link of state terrorism in both Euskal Herria and Spain.

What the media of the regime, especially RTVE, and the spokesmen, from the Minister of Government Manuel Fraga to the civil governor of Navarra, José Ruiz de Gordoa, presented as a Carlist struggle, was much more, and this was denounced in the reports and newspapers that addressed the Montejurra: it was not a confrontation between reactionary and progressive Operation. The path of self-managed socialism and democrats was thus intended to bend the large branch of carlism.

This is the only way to understand the murders that have occurred in front of the monastery of Iratxe and at the top of Montejurra, as well as the “Reconquista” initiative promoted by the right-wing media in the previous days with the collaboration of the Civil Government and the Ministry of the Interior. However, they could not hide the facts, as there were hundreds of witnesses and the graphic impact was very evident through the photographs we recovered for this report.

Events: a first-hand chronicle

On Sunday of May 1976, the usual Carlist crossing of Iratxe began, a tropel of far-right, legionary and fascist Argentinians, Italians and French approached the monastery's esplanade. They went with their pistols and their pores to reconquer at all costs the crossing of Montejurra. From the beginning it became clear that in the face of the useless Carlist self-defense they had no objection to killing and that the most humble answer would be suffocated with blows and blood.

Former commander José Luis Marín García Verde, with gunman with a starry red hat and gabardine, Aniano Jiménez Santos, of the HOAC of Santander, who in the first confrontations went with his hands empty, shot him a lethal shot in the stomach. The murderer, known as a man with gabardine, continued for a few minutes, proudly and provocatively, threatening with a pistol the Carlists who could not believe in the situation, even the civilian guards who had passively witnessed the aggression.

The military could quietly display his pistol, surrounded by a fascist cohort. Next to him was his cousin, Hermenegildo García Lorente, Carlos Ferrando Sales and Fal Macías, son of whom was Carlist Chief Manuel Fal Conde. A little further back, the range of fascists from all over the world: The Argentinian Emilio Berra El Chacal, the Italians Stefano Delle Chiaie and Augustu Cauchi, and the Algerian Jean Pierre Cherid, have been the protagonists. Most were armed with batons and pistols, although the latter were only taken out by García Marín and Berra.

Despite the confusion, believing that the far-right attack had already ended, the Carlists turned to Jurramendi. While the components of the pretender Carlos Hugo Borboi-Parma manifested themselves along the way, it seems that the fascists ascended to the top by the back of the urbanization of Iratxe.

After the killings, the leaders of the assailants went down to Irache. No police controls or obstacles have been found along the way by the police

On the hillside of Montejurra, hundreds of national police officers were in perfect order, as they already knew what would happen later. That was not their area of intervention and that denounced the direct participation of the Civil Government. But these cops were also useless to avoid the second Carlists offensive.

The first protesters reached the top of Mount Montejurra and re-attacked with guns and machine guns. Three or four people were injured in the fog, less than 200 metres from the summit and several more. José Javier Nolasco was shot in the foot and Ricardo García Pellejero, a 20-year-old boy from Estella, was shot in the chest. The latter fell on a blanket, rolling down and down the hill, but by the time he arrived at the ambulance sent by the Red Cross he had already died.

By then, the members of Carlos Hugo's party had already decided to suspend the march and the party leader had already left. In the coming days, the political response they had to give began to be prepared, together with other forces.

After the killings, the chiefs of the assailants, José Arturo Márquez de Prado and Sixto Borboi-Parma, went down to Irache from the top. No police controls or roadblocks were found along the way. From the Iratxe hotel, which since last Tuesday had a luxury hostel, they picked up their shirts and dispersed throughout Madrid, Andalusia and Extremadura. The best known, the reactionary pretender Sixto Borboi-Parma, escaped without problems from Spain.

In the following days, when the photos of the first aggression began to spread and Aniano Jiménez, who was in critical condition, died, the Government of Arias Navarro had to carry out several arrests. The detainee, who was arrested in Huelva and was brought to justice in Estella, has been arrested by the Civil Guard in various media. They did the same with José Arturo Márquez de Prado, a large Extremadura landlord. They were the only detainees and prisoners; months later, with the 1977 Amnesty Act, they were released without trial.

Cherid and Delle Chiaie: two friends of the secret services

The mercenaries and fascists who participated in the attack, often well known for their names and surnames, were not punished. Among them were the activists of fascist organizations unrelated to carlism: Emilio Berra of the Anti-Communist Apostolic Alliance Argentina; Giuseppe Calzona de la Avangoardia Nacional Italiana, Augusto Cauchi and Stefano Delle Chiaie; and Jean Pierre Cherid, Franciscan of Organisation de l’Armée Secreten (OAS).

All of them traveled to the Spanish State on several occasions and found the support of their ministries, especially in the Government and in the Presidential Intelligence Services, in the SECED. In exchange for what? In exchange for the dirty war of 1975-1984. Among those who walked in Montejurra, two stand out: Stefano delle Chiaie and Jean Pierre Cherid.

The first, born in Caserta (Italy), became known to the nickname of Caccola (El Mordoxito) and began his political-military career in the Italian Social Movement (MSI), an ultra-right erechist association. He later went through the fascist organization Ordine Nuovo and finally founded the Avangoardia Nacional. During his activity in Italy he had two objectives: infiltrating extreme left groups, especially anarchists, to commit attacks and provoke provocations, and directly attacking left-wing groups and militants.

The government of Arias Navarro stepped up the progressive evolution of carlism and, incidentally, attempted to create an imbalance in favor of the newly established monarchy.

After several murders in Italy and the defeat of the 1971 coup d’état, Valerio Borghes took refuge in Spain and pioneered the relocation of many Italian fascists. For example, at SECED, created by Carrero Blanco's order, they were given housing and dirty work. From 1975 onwards the dirty war with the acronym BVE and ATE in the French Basque Country was in his hands. In Montejurra, along with Stefano delle Chiaie, there were other caccolesis – members of Caccola –: Augusto Cauchi, Giuseppe Calzona and Mario Ricci, as seen in the photos, and as explained in one of the researches carried out in his day by journalists Ricardo Arques and Melchor Miralles.

Jean Pierre Cherid had fewer followers in Montejurra, but he walked much longer in the dirty war of the state. The writer Paddy Woodworth sees the Algerian killer as one of the pioneers hired by the Spanish State: He has described it as the “paradigm of right-wing mercenaries.” After being a sergeant of the parachutists in the Algerian war, Organisation Armée Secrete (OAS) became an ultra-right armed group. In 1964 he moved to Spain to avoid the penalty of thirty years in prison and during his stay in Madrid he joined Delle Chiaie and began participating in illegal actions of the SECED.

Monte Montejurra was placed in the front line of the aggressors along with Cherid, Augusto Cauchi, Emilio Berra, Fal Macías and the man with gabardine. However, it was much more prominent in the dirty war that resumed in 1978. He is accused of having attacked José Miguel Beñaran Argala on 21 December of that year. Since 1983 it has already been dedicated to the activities of the LAGs. The mercenaries who came from the times of Carrero Blanco and Suárez de la UCD began to perform under these new acronyms the dirty work that the Spanish police could not do on the other side of the border. When the Socialist Party opened up terror on both sides of the border, Jean Pierre Cherid was the most experienced of the criminals. But that's where his career ended. On 19 March 1984, when he was preparing a bomb against a refugee in Biarritz, he exploded him in his hands and lost his life. His body was completely destroyed, so the gendarmes could not know that Cherid was a parachutist and former OAS member.

Once their identity was clarified, numerous data from GAL and its members were detected. It was evident that the one he had been in Montejurra was a leading leader of this group and that he continued to depend on the Spanish authorities in the midst of the dirty war. His widow, for her part, called on the Spanish Government "a lifelong pension", in which she explained that she had worked for years for the police. Thus, he made it clear that the apparatus of the Spanish State were indebted to all these criminals and crimes.

What happened at Montejurra on 9 May 1976 was as strange as it was significant. The jewel became fundamental at the origin of the Franco regime, as they attacked a political force such as carlism. The government of Arias Navarro used fascists and Parisian forces from around the world to crush the progressive political evolution of Carlism and, in passing, create an imbalance in favor of the newly established monarchy. And significant, because, although it is reported immediately after that attack, the impunity of terrorism arising from the State’s sewers has so far had a long and lasting rope.

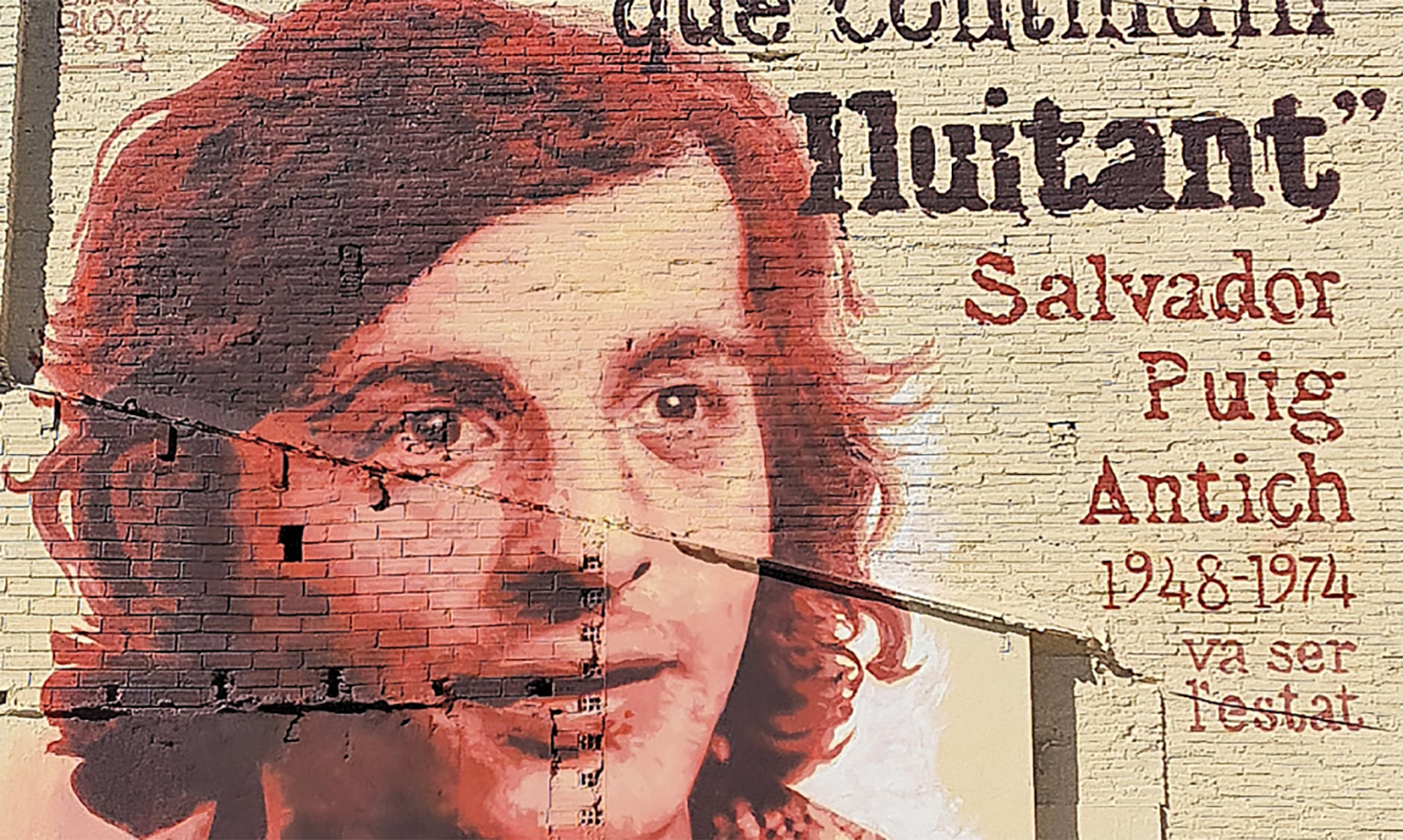

.jpg)

Josu Chuecak duela 40 urteko maiatzaren 9 hartan nekez jakingo zuen eskuetan zuen reflex kamerarekin altxor grafiko bat sortuko zuenik, Jurramendiko ekitaldia puntako egunkarietako foto-erreportariak ari baitziren jarraitzen, El País sortu berrikoak esaterako. Cuadernos para el diálogo aldizkariko irudi honetan ikus daitekeen bezala, Chueca erasotzaileengandik metro gutxitara aritu zen kamerari klik egin eta egin, haietako batek pistolarekin seinalatzeraino.

Erasoa gertatu eta egun batzuetara jabetu zen berak ateratako argazkien balioez. Punto y Hora de Euskal Herria-n argitaratu zituzten lehenik, eta beste mila agerkaritan ondoren.