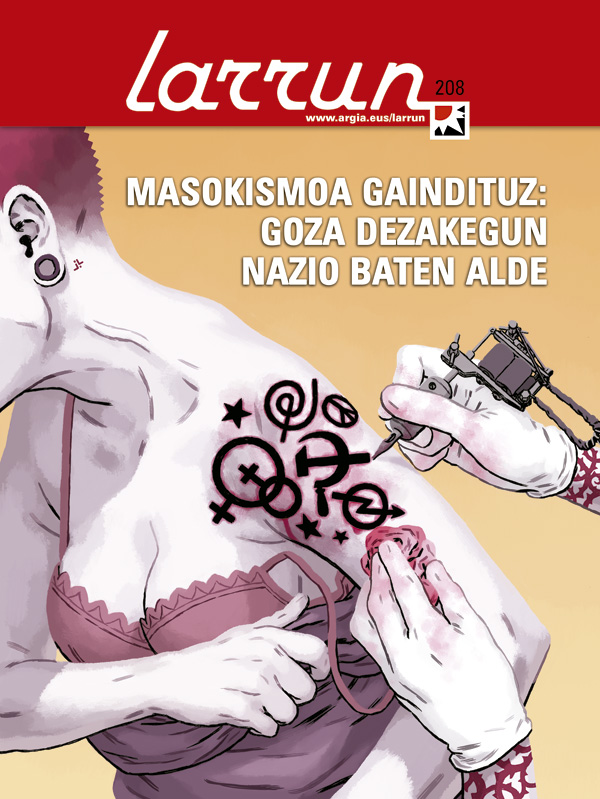

Overcoming masochism: For a nation that we can enjoy

- In recent times, we hear noises of crisis everywhere: On the political left it has as its axis Euskal Herria, in some popular movements that try to reinvent themselves, in the Basque culture... An entire social sector seems to have closed a cycle. And then, it's been seen in the lack of ideological tools for the new situation. Attempts to resolve this situation must be understood as an attempt to lead to independence beyond the theoretical framework of nationalism, which has been the source of many debates in recent years. In this article, Joseba Gabilondo, professor at Michigan State University, has sought to respond to some approaches in this regard to enrich the debate.

Post- and post-leninist phase

It seems that we are in a post-identity phase in the politics of Basque nationalism. In Andoni Olariaga’s introduction to the book Goal of Independence, it makes clear that the classic nationalist paradigm (nation=single subject, a single identity) has been exhausted. "The Basque has to disappear" or "I am not abertzale, I am an independentist", by Unai Apaolaza. The “Basque feminist state” of Jule Goikoetxea also claims the plurality of subjects that put into crisis the classical nationalist model, bringing the non-identity conflict within the nation. Olariaga’s entry, unfortunately, is too close to the postmodern versions of the ‘end of master narratives’ of the 1980s, showing the late nature of this crisis in our environment. Already in the literary criticism of the 1990s we explained that we were in a post-national era (see the remains of my Nation) but due to the poor and poor evolution and updating of the political discourse, the post-national garlic has now reached the Basque political sphere. In philosophy, Mitxelko Uranga also exhibited the national end of his Spectrum: the Basque terrorists (2010).

On the other hand, this post-national and post-national phase coincided with a post-Leninist phase within the left Abertzale. From a Leninist tradition arises the political paradigm in which the party, and in which the ruling elite and/or the armed group of the party, has the capacity and responsibility to think, plan and transfer the political struggle to the militant foundations, has defined the policy of the socialist Left in the twentieth century. If you read Arnaldo Otegi’s time of enlightenment (“KAS no alternative”) or the Abian report, which is still being broadcast in a Leninist way after the last kalapitative elections, makes it clear, at least at the level of desire, that the party must renounce to lead the militant base and listen, restructuring the decision dynamic from the bottom up to the top (Who has written specifically does not say the documents.

The real question is: Should we give up the nation in exchange for a sovereign but unclear future? The answer is not. In a self-sufficient and ‘better lived’ future, a neoliberal and globalized PNV would occupy power. And, therefore, we have to create a very different and more positive response.”

This post-Leninist confluence has given rise to the expansion of an environment defined by the left with negative affectivity: tiredness, frustration, despair, misunderstanding and, above all, disorientation. Complaints have been numerous: “After so many years of struggle, do we have to throw the ‘Basque nation’ away, in favor of an independent project that is not yet clear?” Because pessimism defines the models of Galfarsoro, Apaolaza and Goikoetxea: they define their projects by denying what was there and they are not able to explain a clear political future. They do not answer a fundamental question: “In the end, independence for what, if not to liberate the Basque nation.” Joxe Azurmendi gave the most classic answer to these proposals: “The nation is something objectively describable or nothing.” These pessimistic or anti-national projects, if you ask them in a positive way what they offer, offer an answer that seems very neoliberal: we need a sovereign Basque state to live better. The PNV has already monopolized this discourse, since it has understood its last neoliberal background. And with better results: “Today it is not managed anywhere like in the Basque Country.” This neoliberal and, after all, capitalist message has already coopted for independence, because “living better” and “managing better” are today linked to globalization, unless you define exactly what “living better” means. Thus, what the PNV offers is the possibility of living better without effort (one vote every four years) and without apparent political conflict. EH Bildu does not have the experience of having made such a management policy for years, except in the municipalities, like the PNV; the government of the Council of Gipuzkoa managed for four years is too short an experience. Thus, what the PNV proposes is a less malignant neoliberalism, a more humane capitalism, and as long as Basque independence is not given more precise content and meaning, people will vote for that party because of the climate of fear created by capitalist globalization. Someday later, the neoliberal aspect of the PNV will come to light, but for the time being it can remain based on that ideological ambiguity for years (“as here it is not managed anywhere > lives”).

The real question is: Should we give up the nation in exchange for a sovereign but unclear future? And the answer is not. In a "more transigent and better lived" future, power would fall upon a neoliberal and globalized PNV. And so we have to create a very different and more positive response. To do this, the first thing we need to do is to delve into history and into political theory to get rid of this post-national, post-national and post-Leninist impasse (and so that these hateful “post” prefixes we end up throwing them in the trash of history).

Difference and capitalism: how the value of use and change in globalization is generated

To understand the historical root of this issue, we must understand the historical shock that Marxism and nationalism have had, a problem that has never been solved and that now comes back with the force of marginalized and suppressed ghosts. At the time, Marxism said that the proletarian revolution was the only important and significant struggle. As the revolution expanded, the national problem would disappear into the open. As Benedict Anderson acknowledged in 1983 (Imagined Communities), the main error of Marxism and still one outstanding lesson is nationalism.

Today, updating the same spirit, leftist political philosophers such as Alain Badu or Slavoj Ziz have extended a Marxist denial of nationalism to any difference. The differences between nation, ethnicity, sex, gender and race are second-rate – and also Jacques Rancié, on another level –. This attitude is summed up in the well-known “indifférence à la difference” (L’être et l’événement) of Diu. Both philosophers affirm that all these differences linked by the name of multiculturalism or multiculturalism have already been internalized and co-opted by capitalism, becoming a tool for the exploitation of capitalism. In addition, Zizek captured in a sentence this thought against cultural diversity: “Cultural diversity is a form of racism,” that is, it makes it even more difficult to oppress those individuals who defend cultural diversity (The Ticklish Subject). Galfarsoro has gone beyond the debate between us, saying that these differences are generated by capitalism (“Ethnicity, capitalism, Basque and hegemony”, in the critical Lapiko). Although he did not mention it, he defended in this a thesis by Michel Foucault, which Judith Butler also acknowledged: that the subject creates capitalist states and becomes his representative, defender and guarantor (Gender Trouble).

In this the (post)Marxist and Foucaultian philosophers are completely wrong, because at the end of the day, the Basques, as political subjects, must infer that capitalism (or capitalist states) has created, and therefore, that vasquity is the tool or technology used by capitalism, to oppress us and cooppose us even more. In recent times, following their experiences with foreign (postcolonial) immigrants in France, their view of difference (in favour of racial and ethnic difference) has changed slightly. However, after all, Zizek, Diu, Foucault (and to some extent Butler himself, see Joseph Massad “Reorienting Desire”) are enemies of difference, so these anti-difference philosophers do not help us in our post-identity discussion. At this level, it must be made clear that philosophers who oppose the difference must be denounced and rejected in the Basque Country in order to have a political future. So, like the Proklama, let's say we have to end Zizek and Badu (symbolically clear) to have a post-national and self-sufficient Basque Country.

The causes are two classes. On the one hand, Marxism, which is basically Hegelian, has always understood capitalism as a universal historical process. That is, according to Karl Marx, capitalism should first spread to the whole world, so that humanity (a universalized proletariat) would overcome capitalism and impose communism. Marx claimed, thus, in the case of India, that the most beneficial thing that happened to this people was British colonization, which ultimately accelerated the entry of capitalism into India (“The British Rule in India”). Following the Marxist historiography of Fernand Braudel and Annales, this Hegelian elaboration of Marx reached another philosophical level, since according to that Marxism it became merchandise or merchandise the first universal historical category that made humanity the universal subject of a history: all mankind entering the world of capitalist value. Thus, for Marxism, if merchandise is the only universal category, any other category (nation, gender, sex, race, language…) becomes secondary or secondary and its non-universal particularity denies it the transformative historical-political status. Therefore, we are all capitalists, who live in a global history through merchandise: our Basque or self-sufficient status is of the second order.

On the other hand, in the May revolution of 68, this Marxist discourse became aware of a second phase and thus created a second reason for the indifference (or indifference to human differences) of Marxism. In fact, at the moment other non-capitalist differences entered the political struggle. The independent processes of decolonization made it clear, especially from the hand of Frantz Fanon, that race was also a universal difference, since all mankind was on one side or the other of the division of colonialism (Les Damnés de la Terre). Also feminism, at the hand of Luce Iirigaray and Monique Wittig, claimed the irreducibility of feminism (Speculum de l’autre femme; La pensée straight).

However, the more irreducible the claims, the more it was seen that the final horizon of all of them was the State. These struggles, although declared universal, were made within the State and, in response to a State dynamic, were politically successful to the extent that they received the endorsement or rejection of the State. Feminism, in short, was French, and feminism had constituted itself by states and had fought by states. Revolutionary anti-colonial processes also took place in Cuba, Nicaragua or Nigeria, and according to a State logic. Thus, capitalism has used the State to support and/or co-opt all these struggles and has finally made them an expansion of the State (institutes for women, college or autonomous state…). Hence the mistrust generated by official cultural pluralism among post-Marxist philosophers. The latest statalising processes of these struggles have occurred in Bolivia (and in part in Colombia, Brazil and Venezuela) where the State has turned the generally rationally marked poor classes into subjects of its progressive state policies (the so-called “pink tide”). There, too, the State has adopted an indigenous conception of the world to define its policy and constitution (“living well”), and although the levels of poverty have changed, the main systems of exploitation have not (anodine capitalism/Andean capitalism; see Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, John Beverley and García Linera).

Consequently, it seems that all these struggles that do not have the universal value of capitalism or merchandise have been devoured by the multicultural logic of the State and, at the same time, the history of the proletarian class, which has also been “multiculturalized” and has lost its class identity. The Left has therefore lost its political agenda and has been left without its political subject, without political representation. Thus, and as a reaction, today’s Marxist philosophers have denounced multiculturalism, and yet have argued that the only universal struggle remains the opposite of capitalism. However, the anti-capitalist struggles of these philosophers who deny the difference have a great contradiction: they have no political subject. That is, there is no subject who rebels against capitalism, because every subject today is marked by difference and therefore not universal: for these philosophers, feminism is not an important and universal struggle, also a nationalist and independentist struggle, or an anti-racist and immigrant struggle. All these struggles are significant only to the extent that they embrace capitalism and give up the historical and differential root or base of their struggle (a woman is anticapitalist not because she is a woman, but because she is a subject without difference that opposes capitalism). Thus, and in the words of Ernesto Laclaure, Zizek has remained “waiting for the Martians”, that is, a political subject who is not, and waiting for the emergence of a proletarian class that does not exist, announcing that it will come in the near future with the faith of John the Baptist.

In the Basque Country, this debate has also had its consequences. Both Argala and the rest, in the debates of ETA before Franco's death, repeated the same mistake when he declared that the entire Basque, indigenous and immigrant working class was part of the Basque revolutionary subject. If indeed all Basque workers (autochthonous and immigrants) were proletarian or anti-capitalist subjects, there was no reason to create a sovereign Basque state, since at the end of the day vasquity was a category of secondary transition, on the road to a universal communism and without a nation. And therefore, if ETA and the independence movement have been gradually avoiding the category of the working class or the proletarian class, it is because they have followed the policies adopted by all the states around, turning the proletarian conflict into a state problem, a national problem. The problem that ETA failed to resolve in the 1960s has followed its course and, in the end, has suffered the fate of any political conflict: statehood, the corrupt belief that can be resolved at the state level, from where the sense of independence is pure or absurd today.

"The problem is the configuration of a progressive policy of differences where differences such as nation, sex, gender or race become the starting point of a global policy against the neoliberal state. Alain Badu and Slavoj Zizek have to abandon them, leave us without a political subject, ‘waiting for the Martians’, as the sexist, racist and anti-ethnic oppression of global capitalism continues”

Marxism has not been able to create a socialist policy of differences and has therefore been left without a political subject. Two models have been proposed against, but neither of them has managed to overcome the state as a political horizon. On the one hand, Laclauk and Chantal Mouff have proposed a model of gramsatic hegemony to build a policy of all different political subjects within the state, renouncing the universal validity of capitalism and merchandise (which Mario Zubiaga has spread among us). However, in this model and in the new theorizations proposed by Laclao (On Populist Reason), the political horizon remains the State. Moreover, it is a traditional or classic state prior to neoliberalism and globalization that Laclei has in mind. Laclao does not respond to the new role of the current state in neoliberal globalization: to crush all political differences and to manage and exploit for global capitalism. For their part, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, under the Foucaultian concept of biopolitics, propose a global policy of differences against neoliberal and global capitalism (Common Wealth). However, the understanding of the difference they propose is that of the middle or upper classes of the first world (in short, of the rich university professor) and, homogenizing all the differences, have repeated the problem or contradiction of the official multiculturalism endorsed by the state and the market. It is a policy of inequality that the State can internalize and co-opt, because neither the State nor globalization have taken into account the dynamics being carried out. That is, the model of Hardt and Negri is that of an “extended differential proletarian class”, “multicultural proletarian class” but ultimately built according to the classical Marxist paradigm, according to the proletarian model. The idea is that this multicultural and global proletarian class can be lifted globally against capitalism, without taking into account the role of the neoliberal State again. As Francis Fukuyama said in a review he did for The New York Times, if the most revolutionary model on the left is that of these two philosophers, capitalism can sleep peacefully.

Therefore, once again the problem is the configuration of a progressive policy of differences, where differences such as nation, sex, gender or race become the starting point of a global policy against the neoliberal state. That is, we have to abandon Diu and Zize, because official cultural pluralism has been co-opted by the State, but the differential oppressions (gender, racial, ethnic, linguistic, national…) continue and probably continue to increase. Therefore, negative responses (“no to cultural plurality”) do not solve anything and leave us without a political subject. In other words, we remain “waiting for the Martians”, if we use the laclaust phrase, as the sexist, racist and anti-ethnic oppression of global capitalism continues to advance.

Masochistic Leninist Dynamics of the Marxist Universalist Politics of the Left

The above model has to do directly with the negative situation we suffer in the Basque Country, with our moment of tiredness, frustration and despair. And that is that the Marxist universalist model is the kind of Leninist policy that generates the leader’s militant obedience (HB, ETA, KAS alternative). In the politics of Marxism, the communist party is the only one who can understand the universal dialectic of history in its historical complexity; it should only follow its foundations or bases. This policy is masochistic and leads to a pessimistic situation. As I will explain below, the policies of difference and universality have their libidinal component of enjoyment. And Leninist politics asks him to give up enjoyment, in favour of political masochism.

So far, Basque policy has been Cartesian, as it has thought that it ultimately defines the intellects that had their subjects (from there the “pure” proposal of a sovereign but not national Basque State). So all the proposals have been rational and have been defended in the name of rationality. But, as we know from experience, politics has its libidinal aspect, which until now has not been taken into account in the Basque Country: suffering, enjoyment, masochism, etc. Moreover, until we understand that the libidinal aspect is as important or more important than the rational cartesian, we will be wrong. We need a libidal policy. The following are the first thoughts.

Until now, he had been denied national-political enjoyment, living in a Masochistic policy, on behalf of a subject called a “Basque nation”: we will give up our enjoyment so that the national subject (our sons and daughters) can enjoy it. Aresti’s “Eusko gudariak” or “My Father’s House” are good examples of that ideology. But now, moreover, at a time when independence policy has asked us to renounce the Basque nation, the Masoch-Leninist policy has reached its limit: “Despair of political joy on behalf of a Basque state that we do not yet know what it will be” (and on behalf of a state that, in short, is not going to be Basque). In view of the fact that this Order has been issued in a Leninist manner, the political base or base, i.e. the voters, has been planted: “We will not give up our Basque enjoyment in the name of a state that will not be Basque, of a pure state, and even of a state that cannot assure us that we will live better” (see “On Patriotism and Aeronautics” of Hasier Etxeberria and “Leave a Technical State and Turn Ikurdists into Cooking Rags” of Santi Leone). There, the political basis has been denied to the Leninist-Marxist order to enjoy its pleasure in a masochistic manner. Many, even desperate, have voted for parties like Podemos. Yes, they have been asked to give up the Basque goce: a referendum perhaps, but not independence, because in Madrid Pablo Iglesias is proud to be the Spanish patriot. But at least they have been made a fair and non-Leninist proposal for a social and economic enjoyment: Not even Paul Iglesias appeared in Euskal Herria, further dissolving the ghost of Lenin (i.e., the absence of Churches helped Podemos in Basque Country). Young people, above all, have responded positively to Podemos’s proposal: “Yes, we can, yes, we can change the economic and social situation, even if we have to give up the Basque, or we have to postpone our Euskaldun enjoyment in a masochistic way.”

"A post-national policy must, first of all, give up Leninist masochism ("obey the leader, give up your enjoyment, in the name of

a future national state, of your most Basque and happy sons and daughters") and positional masochism ("give up your Basque enjoyment to a pure and joyless state that is not Basque and that may help us live better").

To understand the Masochistic sense of jouissance caused by Leninism, we must look again at the PNV. Each and every one of the non-indense political formulas he has proposed, and above all the last, “foral nation”, ambiguous, without precise meaning and, ultimately, retrograde, offer the voter a non-masochistic goce: “Do not give up anything, you are proud of your national-foral past, you are a quasi-sovereign subject and, furthermore, as we have shown that we manage that pleasure well, vote, because you will live better with us.” The PNV has problems with young people, insofar as young people do not personally see the advantages of this neoliberal management. But the PNV offers a non-masochist libidinal policy (which is neurotic, but we have no space to explain it).

Therefore, a post-national policy must first of all renounce the Leninist masochism (“renouncing the goce which obeyed the leader, in the name of a future national state, on behalf of your most Euskaldunes and happy children”) and post-Christian masochism (“renouncing your Basque enjoyment for a pure and non-enjoyment state, which may help us to live better”).

Today we know that the problem is the state, so it is clear that the traditional nationalist subject model has no future. We cannot achieve independence on behalf of a homogeneous and unique Basque subject, as the State will assume all the differences and will tread them on behalf of the Basque. If we need a state, and that state will not oppress us in the name of the economic logic of global neoliberalism (there is no money for the citizens, just for the banks), that requires another policy and another non-masochistic enjoyment: we need a state that allows us to enjoy all our differences and that helps us in the fight of globalisation and neoliberalism.

Thus, this state must be Euskaldun, but also immigrant, women, youth, all sexes, all races… as the only limit, respect for the differences of others and the global enjoyment of those differences (at that level enjoyment in this state would be neurotic, but not masochist). If the PNV offers us a false state, never totally inadequate to live better, the left should offer a Basque state that makes us enjoy all our historical differences, where our enjoyment becomes a guarantee against the oppressive policies of global neoliberalism.

Managed foral nation vs. global subaltern nation

Thus, our history – and the seemingly stable signs (folkloric and ethnic culture) that we have frozen from that history – is not unique, stable, Hegelian and, therefore, neither national nor identity. The last ideological formulation of the PNV, the “foral nation”, conceals that the Basque history from the 16th century onwards is the history that a fuerist elite has trampled and exploited a subaltern or low-class majority, arguing the difference of the Basque in the Spanish state (the inhabitants and the oldest languages of Spain, the universal hydalguide, the pactist nature of the forces…). In this history of post-national exploitation, the Basque language is not our “national language”. The Basque language, as a non-national language, would not allow the double game of a foral elite: to tread on the subordinate classes and to use the “identity” of those classes to legitimize themselves before the Spanish crown/state. The Basque language would be precisely the language used by a subaltern majority to cope with this exploitation and to live against this exploration. Therefore, Euskera is the chronicle of a non-identity post-national exploitation. The proposal by Eduardo Apodaka (Identity and Anomaly) goes in that direction, the difference goes in that direction.

But Euskera is not the only one in Euskal Herria, it also serves to understand and structure other farms. Therefore, Euskera or Vasquidad do not define exclusively Euskaldun citizenship, but it becomes the language and reference of many other non-Euskaldunes experiences, including immigrants. That is, the Spanish of the exploited immigrants who came to Euskal Herria should also understand it as a form of Euskara, and therefore accept it as one more dialect. That subaltern is the language of the history of many immigrant Basques, and so we should accept it and enjoy it. In other words, this Castilian language (and often the Asturian, the Aragonese and other more recent subaltern languages such as the Arabic language) is not the same that has been officially used by the institutions of the State, which are two different languages and thus should be differentiated. Thus, Basque history would become the history of the exploitation of a subaltern and plural and the culture that that history has given: our “ethnicity” and our delicious “historical memory”, that is, the ununified, historical and political essence of our nation. And to the extent that this story gives us its foundations and roots, it also offers us the way to understand the global neoliberal exploitation that is currently being restructured with the collaboration of an elite of the Euskaldun/basko class. We can enjoy this story. It also offers us two things: a narrative for current exploitation and a historical continuity. That is, it gives us political joy.

We do not need to evict the Basque nation. In another post-national and post-national history, the word

‘Basque nation’ offers us a much more complex, heterogeneous and diverse history for our political enjoyment, moving the elites to the other side of the antagony, towards the enemy, in their historical continuity”

Thus, we do not need to evict the Basque nation. In this other post-national and post-Soviet history, the word “Basque nation” offers us a much more complex, heterogeneous and diverse history for our political enjoyment, moving the elites across the antagony, on the other side of the enemy, in their historical continuity (principal Basque relatives > cavalry > elite neoliberal class of the PNV…). And finally, this story gives meaning to an empty and absurd state that, otherwise, would only be Basque by its names (a state that wants and cannot be Basque). And it would help us to understand that State, not as an end and goal, but as a further phase of a longer, more enjoyable story that doesn't end with the State, because we know that globalization turns the State into an oppressive institution. In my book Before Babel I have tried to explain the aspect that this subaltern and differential history can have, taking as a starting point the literature, but in the end laying a post-national and non-identity basis for a non-national but joyful and differential Basque literature.

Finally, this starting point helps us solve another problem: Who is going to lead that state? The Left, for the time being, wants to impose the liberal model of the state (democracy, separation of powers…). But in many newly created states or in many Europarties (Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Poland, Hungary…) as you can see, history has an enormous weight, and if history is not understood, we can end up in a state that has a form of liberal but authoritarian democracy.

Resistance to capitalism and reterritorialization, primacy of value over

To understand why the history of the oppression of our differences is going to help us fight capitalism and make that struggle joyful, we have to go back to the Marxist theory. Although it may initially appear to be too theoretical a debate, it is necessary to correct the political situation on the left. Today, the ideological horizon of the left has culminated in a series of failed attempts to unsuccessfully maintain the achievements of the welfare state of the then social democracy. Today the left has ended up being a shameful shadow of classical socialdemocracy (the aim is for a rectified Sweden to be installed in most states, while Sweden, for its part, is neo-liberalising). It is enough to consult the EH Bildu 2015 programme or the Abian report.

The problem is at the beginning of Marxism. Although for Marxism things have a value of use (use value), capitalism does not take this value of use as a starting point, but the exchange value (exchange value), that is, the value of exchange of goods that is measured by price, that is, by money. And finally, Marxism proposes that when a man sells his labor force to the bourgeois class in exchange for a price, this class does not give him a real barter value, but always acquires a difference (surplus value, surplus value, Mehrwert). In short, the tendency of capitalism would be to add that surplus value, since the last form of capitalism is financial capitalism (which accumulates surplus value by selling and buying money). Thus, the value of use disappears from the history of capitalism in Marxism. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari are probably the ones who have most criticized this orthodox understanding of capitalism and those who have tried to give another model in the 1980s.

"Capitalism is in a game of permanent re-territorialization. Thus, our historical differences outweigh capitalism: capitalism cannot master, accumulate and, ultimately, fully exploit human difference. There is therefore no final moment of progress in which a global proletariat will derail the global bourgeoisie. Capitalism is limited and blind, and it always follows the construction of human difference, restructuring and re-territorializing with this difference"

According to the deliuzo-guatarian model, capitalism is not formed on the value of exchange, but on the value of use. Capitalism has no direction or goal: it spreads in the crisis or catastrophe movement – there is no Hegelian revolutionary end. It always tends to use and abandon active activities, objects and values from outside or from the past (tourism, urban areas, industrialization of organic agriculture, Game of Thrones mediebalist base, most fashions…). Capitalism is in a constant game of virtualization. Thus, our historical differences outweigh capitalism: capitalism cannot master, accumulate and, ultimately, fully exploit human difference. There is therefore no final moment of progress in which a global proletariat will derail the global bourgeoisie. Capitalism is limited and blind, and it always follows the construction of human difference and is restructured and reterritorialized with respect to this difference (retritorialisation).

The proposal of Hala Deleuze and Guattari is to increase those differences and increase the desire and enjoyment of those differences until capitalism dissolves or dissolves, that is, until those differences outweigh capitalism. In other words, according to these philosophers, capitalism cannot be opposed – or capitalism can be derailed through revolution – but its logic must be broadened until capitalism ceases to be capitalist in that growth. The proposal seems to be a very utopian and even unrealistic day if we take into account the strength and influence of current capitalism. However, this proposal sets the starting point for all policies in practice to enjoy a plural and different history than the one we are talking about, and at that level it responds, albeit theoretically, to the situation of the current Basque policy. In short, it allows us to go beyond a failed policy to keep patching the outdated project of Social Democracy. I have tried to explain the unique aspect that this proposal may have in globalisation, in my new book that will come out soon: Globalization and New Middle Ages (2017).

Non-subordinate independence: Social Democratic border on the left

The semi-neoliberal independence ideology of “living better” has no future, nor the leftist ideology that seeks to paralyze the project of social democracy. Moreover, coming to a sovereign Basque state, a project of independence that does not have a proposal to cope with the strength of neoliberalism and global capitalism will end up being devoured by neoliberalism (see Greece and Syriza). A process of independence that ignores our history can give us a seemingly liberal but ultimately authoritarian state (or civil war). We must set in motion a more historical, differential and libidinal thought. Otherwise, we will end up with a subordinate independence. I hope that, by developing these ideas, a further book can be drawn up later on: Basque ideology: ethnic nation and post-nationalism.

Independentziaren aldeko ekimenak aurrera eramateko baliabide faltagatik "itzaliko" da. Aurretik, Euskal Herri osoko 101 udaletan independentzia mozioak erregistratuko dituztela iragarri dute, euskal errepublikaren aldeko prozesuan urratsak egiteko. Baliabide faltaz... [+]

Kirola eta aldarrikapena uztartuz, maiatzaren 24an Bilbo gazteria independentistaz beteko da. Lasterketa honen bitartez, Euskal Herriaren askatasunaren aldeko balioei lekua egin nahi diote gazteek, independentziarako bidean daudela erakutsiz.

As we know, the Institutional Independence of Hego Euskal Herria has begun a certain roadmap. Signing a new pact with the Spanish State. This path uses some main variables or premises. Thus: The PSOE is a leftist party, the Spanish State is recyclable and it is up to the... [+]

It is not easy to understand what is happening in Catalonia. Certainly. We can end the 2017 process, but it remains to be seen whether independence will be able to start a new process of liberation.

If independence had been maintained in most elections, there would be another... [+]

Xabier Zabaltza Perez-Nievas historialaria, idazlea eta EHUko irakasleak 'Euskal Herria heterodoxiatik' izeneko liburua plazaratu berri du. Bertan dio Euskal Herria ezinbestean euskara eta euskal kulturaren bidez eraiki behar dela eta horretarako funtsezkoa dela euskara... [+]

“The most Abertzale parliament of all time” vs. “Independence is at the historical lows.” These two statements have been heard in recent times and have increased following the elections held on 21 April in Araba, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa. These two phrases, considered as... [+]

Tristeziaz hartu du Atarrabiako alkateak Nafarroako Justizia Epaitegi Nagusiaren epaia. Euskal Herriko armarria ezabatu beharko du herriko frontoiko hormatik. “Bere garaian ikurriña kentzera behartu ziguten bezala” adierazi du Euskalerria Irratian Mikel... [+]

The independence of Euskal Herria and Catalonia is the object of study abroad. The University of Nevada, in Reno, USA, has just published an important book Pro-independence movements in the Basque Country and Catalunya, under the responsibility of three experts: Xabier Irujo,... [+]

These are dark times for the Basque nation. And in the nation I say, not only do I speak in this language and in the nation, but I speak of the Basque nation of the citizens that we want to endow ourselves with the highest political legal order, of which we form the Vascophiles... [+]