Indignados from the 18th century

- In 1766, the popular revolt burned the corners of the Urola and other places. Furious with the lords who began to speculate with hunger, they arbored the flag of equality. In the great encyclopedias, however, only the names of the capitalists who crushed the revolt appear, dressed in the costume of enlightenment. There is hardly any literature for poor Basques.

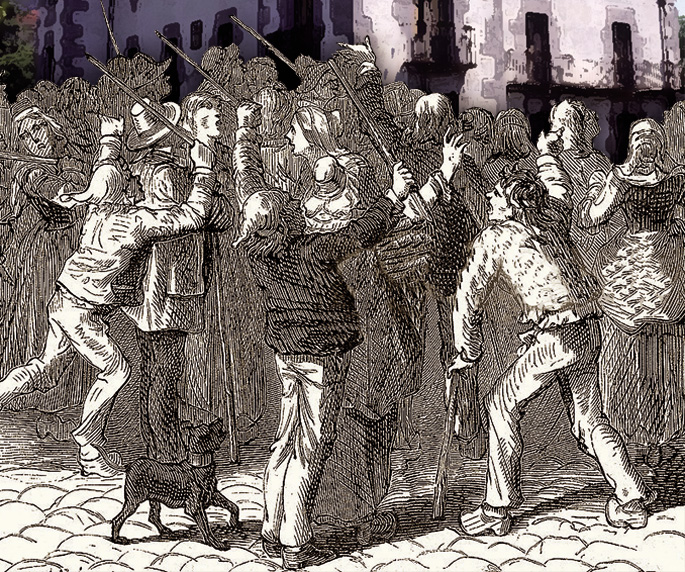

At the height of the Egurbide ferreria of Azkoitia, under the motto “Geldi! Stop! they heard two women in charge. The ferrons and the shoemakers who came out on the road were determined to leave in the camp those burgers full of grain. It was April 14, for the fall of the afternoon, when the rebels owned Azkoitia and Azpeitia and in the coming days the clashes extended to all Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia and Álava. What was most demanded was to lower the price of bread, but not only that, but also the response of a hungry people to the excesses of the great.

It's been 250 years since the insurrection occurred. At least a century ago, it had been another eye of a long chain of social multisengual handkerchiefs and cylindrical. In the 17th century, the true Matalaz Xiberutarras rose up against the privatization of the land, and the Baserritarras were devoted to the Libreclastic lords in the 18th century.

In Europe, these events occurred more frequently. In England the closures of popular lands, in Scandinavia the collectors, in Porto the monopoly of spirits… There was no reason to go out to the streets to tenants and salaried workers who could not eat more than bread. In France, from 1724 to 1789, literary critic Daniel Mornet reported 100 raised citizens, half of whom in the last 25 years. Economic liberalism, in any case, solved business and suffering.

It is believed that the rebel word comes from Martin, the saint of the ferrons, and it is said that it was used for the first time in 1718. “A revolt as direct as ‘hands’ in the shadow…,” Orixe wrote in the national poem Euskaldunak. On this occasion, the revolt led to the transfer of customs to the coast and to the Pyrenees, an increase in taxes on raw materials, while in 1766 the real permission granted to traffickers to play with food prices was exceeded. In both cases, poor peasants and workers, with no choice but to fatten tents, paid the toll of usury.

Two measures for wheat

Kanpandor's bells vibrate in Azkoitia, neighbors approach, responding to the insurgents' call. And the lords have surrendered, removing the wig, saying that they will not carry grain out until the next harvest. The wheat boxes and the pieces filled the quay's path to multiply the export profit.

The rage of years cannot be appeased with a promise. In neighbouring Azpeitia there has also been a great stir in the afternoon, when the shadows have elongated. From one town to another the rebels move, here those of Beizama, there those of Urrestilla, the quarries that are making the shrine of Loiola… In Azpeitia they have gone into the houses of some magnates and have accumulated the measures for the grain in the center of the plaza: “There are two measures, one for buying and the other for selling grain, and since the two are used, more than the tiredness that others can afford the bread,” says Iñigo Aranbarri in the great book Txanton Garrote (Pamiela, 2016).

Aranbarri has researched closely what happened in 1766, through first-hand sources and literature, in addition to completing the chronicle of the revolt, the Azkoitiarra writer makes a ferocious criticism of the claudicating society of before and today: “The wrong way of government: this practice that makes the rulers haudillos”.

In 1933, Ildefonso Gurrutxaga took a detailed photograph of Azpeitia's economy in Yakintza magazine, a pioneering article written on revolt. Historians stated that the ferrerias were in absolute decline and that the peasants were in the worst situation since the Middle Ages. In the 18th century, four out of every five farms had been rented in that village, and their owners preferred to collect their rent in grain and keep the farms scrambled, while the tenants had breakfast in the sun. There was a great patrimonial concentration. Nine owners of Azpeitia – including, of course, Enparandarrak, the Marquis of Narros, the family of Mayor Basazabal… – accounted for almost half of the local income. No wonder that in that Izarraizpe two and a half centuries ago there is a movement similar to the Occupy, from here you can hear the cry “We are 99%!”.

“There is neither us nor any other mayor!”

Historians have linked the revolt of 1766 against the orders of Marquis Esquilache in Madrid with a popular uprising that began in March and spread throughout the kingdom of Spain. But at a time when the railways did not exist, it is more reasonable to think that the sufferings and sorrows of our towns and neighbourhoods were the seeds of cholera. Previously, secret meetings had been held in Azpeitia and Azkoitia to attack the stores of merchants in San Sebastian.

On April 9, an anonymous pin signed in San Sebastian appeared: “Guciac lords of Azpeitia, they serve you well, each one of you gives your life well, otherwise you lose the fire and (...) the guizonac or machino oriec of the people who was opposite chit”. The anonymous says that the revolt is already underway, that the rebels have attacked and that they are now on their way to Azpeitia, even though maize and wheat are being lowered, “I don’t mean guciac.” It is obvious that it is a deception, because it was written a few days before the revolt began, but the evidence of the pain that was noticeable is very clear.

A young scribe of Urrestilla, accused of writing a letter of sedition, was arrested on the order of the mayor of Azpeitia, Vicente Basazabal. Boy of the release, will be the first thing asked by the ferrons and other hookers who rushed into the Azpeitia City Hall on 14 April. Gipuzkoa’s powerful deputy general, Joseph Joaquin Enparan, has asked for respect for one of those unfortunate people who are stirring to take the hat off to justice and the mayor: "What a mayor and what a devil! There is neither us nor any other mayor!” his answer. Where have we heard that? The best mayor, the best president, the people.

The following day, the capitulations of the municipalities come in line: First in Azkoitia, then in Azpeitia, then in Deba, in Getaria… The chapters signed in each town respond to local social problems. In Getaria, for example, the people ' s children called for increased compensation for forced boarding in the army, or for the pier ' s house to be republished for use by the Sardines Company. For Xabier Alberdi and Carlos Rilova, who have investigated the case of coastal villages, these capitulations “can be considered as a first sign of awareness of the class condition”.

Let everyone vote

The atmosphere in Azpeitia has returned to calm, almost a week after Sunday hangs: “On Sunday afternoon people were more insolent than ever,” says the Marquis of Narros in his testimony – as you can read in the document rescued for the book Aranbarri –. He also regretted the fear that Azkoitia’s primicide had “died and burned” in the last sighting. They are more afraid of the collector than the gentleman who, with his taxes, burdens a cold.

And once the capitulation began, to the great hordago: the rebels have also called for the great teachers to be limited and distributed among all, and for open municipalities to be made... and that everyone should have their vote,” the marquis said, surprised. “A revolutionary Ayala Plan of Mexico in 1766? – says Aranbarri – An agricultural reform? What we are at the Second Congress of Spain. In the republic? In Sovieta Urolaldea?” No. Farmers have only asked for what had been taken away from them before.

The economic elite had monopolized the control of public institutions in recent times, not for the benefit of all, but of their interests, through which the networks of relations were generated. People's assemblies or open city halls are over, direct democracy is over. In the 17th and 18th centuries, impossible economic conditions were established so that humble citizens could not have access to public office, especially to have a “minimum” heritage. For example, in Gordexola, 400 women were required to be mayors, in Oñati 500 and in Azkoitia 200.

They will not forgive the passage of the red line to the rebels who have always been above the head of the people, call solemn, illustrate or caste.

Social control was established through the sonorization of Cisco, as well as the imposition of a dominant language. You had to know Spanish or romance for the palaces. So, as Joxe Azurmendi says in his masterpiece, “the lords invented another trap to remove the opposition.”

But it was impossible to fulfil this condition, because the majority – even the people’s lords – only spoke that which was called the Vasconian vulgar language; not because in few villages the rulers were Basque monolinguals, because there was no one who knew Castilian. Many of them were disabled by the central administration, such as the mayor of Zaldibia, who was dismissed in 1742 for not knowing Spanish, and when social conflicts occurred, a serious problem arose. It is curious to see how in times of revolt documents in Basque multiply in general meetings and in municipalities. In 1766, the capitulations of Azpeitia were also translated into Basque by his abbot, so everyone understood it.

Experience

Take the hat off to authority? In the noisy April the poor made the same humiliation as for a long time pass: he was taken away by the wig, he was forced to kiss his hands, he had to carry his covers and dance in the way of the “peasants”. Violence and the threat, but above all at a symbolic level, were gestures to free themselves from the exploitation of the oligarchy. Processions were held and victory was celebrated until late in the morning.

In Azpeitia, with the priests in the hands and hands, a soka-dantza has been formed “people of all genders, without any difference”, they are two hundred or more, practicing Basque egalitarianism.

They will not forgive the passage of the red line to those who have always walked above the head of the people, call solemnly, enlighten or caste. Aranbarri has perfectly identified this classism in the opera El borracho burlado del conde Peñaflorida, premiered two years before the revolt. It's not only a matter of money, it's also a moral question. Txepetxa wanted to turn it into a canastarro, as the drunk of the opera Txanton Garrote dreamed, and as this one had an experience, they will also receive it. Experience in Urolalde of 1766, experience in Navarra of 1936, experience in Greece of 2015.

Francisco Xabier Munibe, Count of Peñaflorida and founder of the Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País, is on the sale of Iturrioz on April 24 to receive calmly the troops of Donostialdea. These are 300 soldiers from the Irish regiment, plus 1,500 recruited at Errenteria, Oiartzun, Urnieta and Hernani, under the orders of the Mayor of San Sebastian, Manuel María Arriola. The show started financed by merchants from the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana in Caracas.

First of all they have addressed Loyola, where the operators have distinguished themselves in the session, and they have surprised them all while they work. Then there is a discussion with the parish priest of the Shrine, since the Corrector accuses the Jesuits of being in favor of the rebels, an excuse for expelling for once the uncomfortable order of the kingdom of Spain.

In the Urola and Must-see basins, the small revolution has already been extinguished, but the black lists have long been formed. In total, 70 people will be captured and taken to the prisons of Donostia and Rentería by foot – one will die on the road and the other, when he flees, will be seriously wounded with bayonets. Many of the people in Errenteria are women: Maria Antonia de Alberdi, 51 years old; Michaela de Larrañaga, 33 years old; Mari Josepha de Urquina, 38 years old; Ana Maria de Elorza, 50 years old; Maria Brigida de Arteaga, 26 years old – sent home for pregnancy…

The role of women in the riots was not the same as in the riots in 1718, as in the riots against the tobacco monopoly in Lapurdi in 1773 and in 1784. These were conflicts of social origin and the ones that suffered the most from the attack of the new oligarchs were those of the margins that endured the weight of the domestic economy. In 1766, they were accused of spreading rumours: one year after the uprising, several women were prosecuted, gathered in the vicinity of shops and bread ovens, because it was said that the Jesuits would return to Loyola.

Aranbarri quotes 439 convicted in his book. For many the incarceration, for others the exile, the compulsory work and services, the fines... The false judges did not walk calmly, some of those who started the rebellion on 14 April in Azkoitia led the streets bound by their mouth and hands and by punishment. Then, ten years of exile in a dark prison in Africa, without too much hope of survival. Has it so far been agreed that limestone sculptures should be made in their honour? At least they deserve a small plate on some street.

For centuries, the increase in the goods needed for subsistence, or scarcity, rebellion and protest have led to a large number of citizens. Oppressed people have always been willing to provoke confrontations and disturbances when there is a lack of means to meet basic needs... [+]

1766an gariaren prezio igoerak eragindako matxinada ikertzen ari da Hide (Yokohama, 1994), doktore tesirako. Segurako Udal artxibora jo du lanaren inguruko dokumentazioa bilatzeko.

Azpeitiko Kultur Mahaiak egindako proposamena aho batez onartu zuten ohiko udalbatzarrean eta "galtzaileen borroka" gogora ekarriko duen kalea izango du herriak.

1766ko herritarren altxamendua gogoratzeko egitarauaren berri emango dute ostegun honetan Azpeitian. Matxinada sozial haren oinarriak inoiz baino biziago daude kapitalismoaren krisiarekin.

Ez da Madrilgo plaza nagusiraino joan behar behartsuenganako jarrera umilianteak ikusteko. Nahikoa da Euskal Herrian 250 urte atzera egitea: El borracho burlado-k ederki laburbiltzen du orduko eta gaurko eliteen umore zanpatzailea.