"We spend 40 years with our lips tied, as mute as fish."

- How many living witnesses survive and participate in the Spanish Civil War of 1936? How many are those who are able to tell the truth of Gabriel Aresti? How many were those who, after being on the front line of war, had them in the workers' battalions? Luis Ortiz Alfau is almost seen only when he is 100 years old...

You're talking about war, but you hadn't done it long ago.

For 40 years, I had to be silent and mute, because you couldn't speak. It was Franco's black dictatorship. I am now a hundred years old and with your help I have no choice but to try what happened. He was nineteen years old when the war broke out. I signed up for a battalion from the Republican Left.

Nineteen years and war.

I had nothing but my life in my head, I had a girlfriend, I was working, I was studying. I mean, I didn't have political affiliation, but my father was a Republican, and we the children admired us a lot, we thought like him, and so I went. I went to war in the schools of the Bank of Muxika in Bilbao. He was studying television and correspondence morse with a Californian institute. I knew something, and they put me on broadcasts. We didn't have a phone, we didn't have flags, we didn't have rifles, but we were nineteen or twenty years old, and we thought we would swallow the world.

What happened after the inscription for war?

The battalion was called Captain Casero, I think Casero was a Republican military, shot during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. The name of that battalion was in his honor. They took us to the front of Álava, Otxandio, Legutiano… there. It was the first thing you had to do, but there was no way. They had destroyed us terribly because we didn't have a single boss. They are in charge of putting those who had studies: ours was a teacher of Ondarroa, a good teacher, surely, but he did not understand anything about the war. The transmission lieutenant was also from the marina, who was doing internships on a boat. To the devil with that!

The Alavese front didn't last.

There was no way to last. Not a gun or anything. From there they took us to Intxorta, to Elgeta. There, yes, we lasted three months. If they lost it, they would enter Bilbao, Santander and the whole northern part of Spain. Unfortunately, that was what happened. Many people died in Intxorta, on both sides. There every day there were fighting in the trenches, killed and wounded every day, and we were relieved once a week. I remember that our company went down to Gernika, to rest, to the Errenteria neighborhood. There was a bridge, near where they had thrown a bomb, and our task was to collect the dead and the wounded from the trucks and cars. Sometimes I dream, what was that! After bombing Gernika, they bombed Durango, Zornotza, Galdakao… and we got to Artxanda, going back. In the campas of Asua, near the hermitage of San Roque, the casino rises. Our people were shooting in the windows. But it was also bombed by the rebels' planes.

And you?

The soldiers dispersed us and went back to our company. In one of them I rested in a house in front of the Alhóndiga de Bilbao. They had left it empty. We slept there and went out the next day, because the rebels were near. Along the way we headed towards Castro, where we met a great multitude of men and women, children and soldiers. They came to Castro and fed us: rice. And again, the battalions formed. With such a setback, the battalions faded and formed new ones, 84, 90 or whatever is from the Basque army. There was no longer a nationalist battalion, no socialist, no more.

"And they gave us the house. Deputy, civil guard. About us, of night worship. The third is that of the union. Fourth...

Where did you see later?

We arrived in Mieres (Asturias) and by then there was everything in the battalions: people from here and there. We return from Mieres to Santander, on the Shield. The commander gave the order and was going to take it to the front row, with a gun, and threw me back five or six meters. He broke me three ribs and took me to the hospital in Santander. There they were three days, and we were told that the Italians were about to enter. In one way or another, I went out and jumped into a fishing boat, between women, children and soldiers, full of people. We were taken to La Rochelle, where two rows were formed, one on one side and we on the other, to go to Barcelona. Indalecio Prieto, Army Minister, made a battalion of skiers in Benasque [Huesca] for the Basques: everything was a beautiful uniform, skiing, etc.

The battalion of Basque skiers?

Yes, yes. And we thought that was just going to be a party! Not in vain, within a month we had to throw everything in stone and went to the front of Huesca. We arrived there, two days ago and we have to go back, again, to Barcelona. The battalions and La Seu d’ Urgellera are again completed. The companies were governed by anarchists and communists. I was appointed administrative sergeant.

Administrative sergeant? What does that mean?

I took care of my meals, my clothes and things like that. Before I start, I'll tell you what happened to me. When I was working at the battalion as a food manager, I could see that the officers picked it up and sold it in the rear, or gave it to their peers, or used it to exchange. They used for their benefit what belonged to the entire battalion. I protested and wrote. They imposed the law of the army on me, took my pistol off and put me in the cell, in the oven to make bread from a farmhouse. In addition, I was sentenced to the workers’ battalions at the rear, together with the Franco prisoners, to make the road. The commander told me that an escort would take me there, but that the escort had an order to leave me free on the way and go to the regiment corresponding to La Seu d’Urgell. On February 10, 1939, we went to France, Argeles-sur-Mer, where the Spanish Civil War ended for me.

Instead of keeping you in the workers' battalions.

Yes. We got bad for a month on the beaches of Argeles-sur-Mer. There was no roof terrace, bathroom, nothing. The Basque Government began to help us right away. Petaine refused to let us go and ordered them to camp. Lehendakari Agirre tried to do the camps for us near Euskal Herria, but the heads of the people there did not want. Finally, the camp was set up in Gurs. Taking advantage of the barracks of World War I, the French made us more.

When did you arrive at Gurs?

14 June 1939. We arrived 176 Euskaldunes, the first Euskaldunes. But I was only six months in Gurs. He's near Oloron and the Navarros were coming to do the alpargata campaign. And on Sunday, the Navarros coming by bicycle, to see and to see: “What do you need?” and we wrote on a papelite: “I’m like that, I’m in that barracks, I need a razor blade and a soap. And it would take an ounce of chocolate!”… And the next Sunday I was there, most young people, who brought something. Wanting to help.

You say that you were six months.

Yes. I was once called to the tour barracks. A corpulent man and a girl were walking around. The man was French, engineer, and the girl, refugee, Donostiarra, was called Adela. Fermín Calbetón lived on the street. “I met one from Bilbao, who was your family’s neighborhood, and I told Mr. Morin, the man next to him, if he’s going to get you out of here to help us.” That Frenchman, a socialist of course, had gathered in the village next door, in La Gerche, an old brick factory, hundreds of women and girls, all of them refugees from Spain. There they had beds, they had to eat... they were very well cared for. And they wanted me to help them take their bills, distribute their meals. I went to live in Mr Morin's house. But the Second World War came and Morin mobilized -- he was an engineer and captain of the reserve -- and his two sons, and I stayed with my patron alone. But it wasn't what it looked like, and I got in touch with my family in Bilbao, of course.

And did you come?

Yes. He was elegantly dressed, wearing a suit and holding a leather suitcase in his hand. When I got to the front, I went through Hendaia, and on the bridge, lots of civil and Falangist guards. They liked the suitcase and they took it off. And they took me to the chocolate factory in Elgorriaga, to a pavilion, like all the young people, and we would have been hundreds. I took off my suitcase and put all the documents in. Only a small photo was saved in the pocket. We spent a few days there, and the bilbaínos brought us to the University of Deusto, imprisoned, without documents.

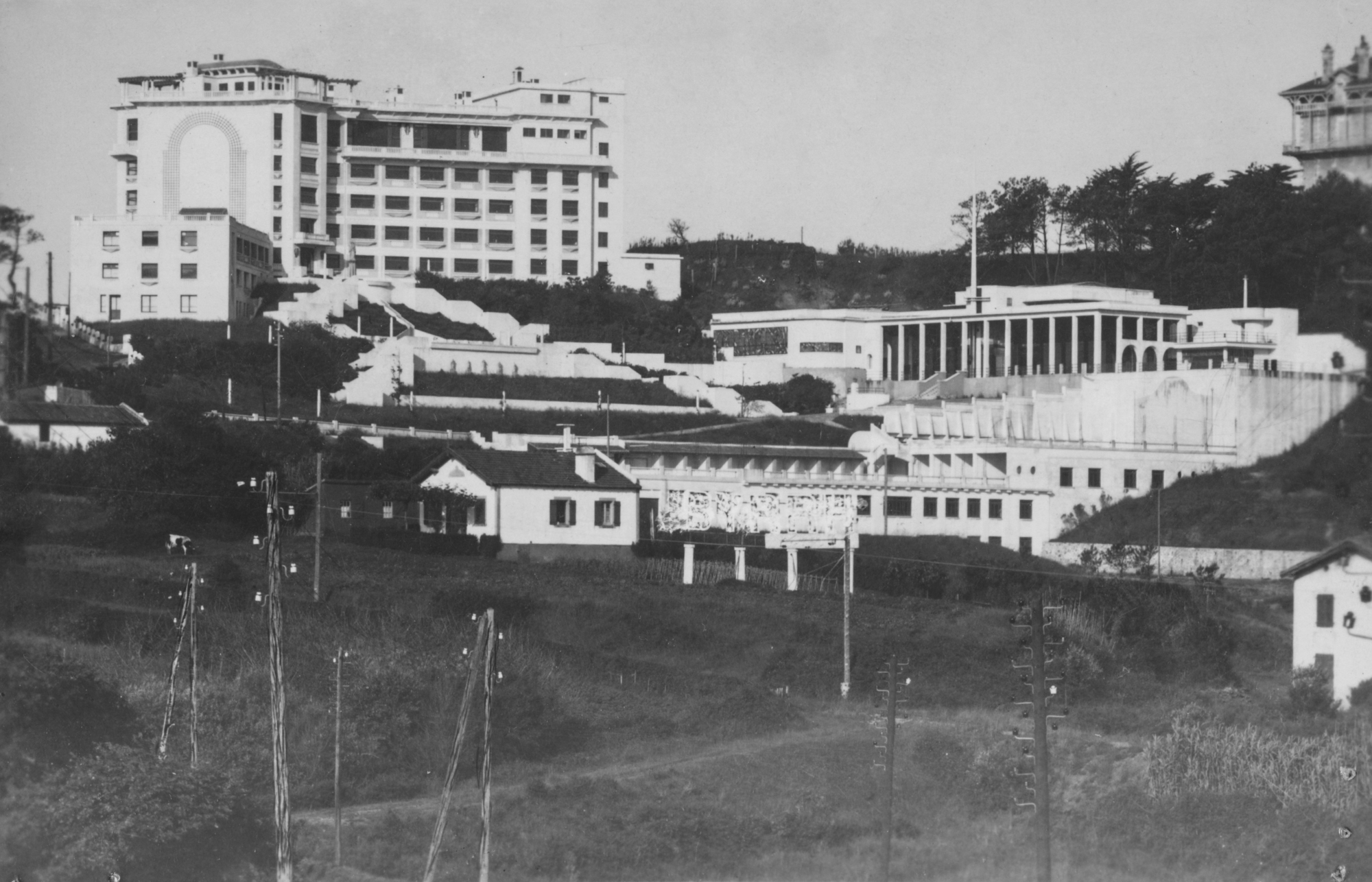

Was Deusto University a prison?

Jail and bad, plus. They saw me -- young, no documents -- and they didn't have to think much. We will get back to the truck, along with other young people: To the camp of Miranda de Ebro. The workers’ battalions were formed there. We were in Errenteria-Oiartzun: Gaintxurizketa, Babylon, Peñas de Aia… six months. Then to Miranda, from there to Pamplona and to the Irati train. We were taken to Lumbier and from there to Vidángoz in the battalion of the 38 workers, which had three departments, the first of which was in Vidángoz, the second in Igal and the third in Roncal. We built the new road from Vidángoz to Igal. Others made Igal to Roncal. In Oiartzun we ate more or less. The one from Navarre, on the other hand, was terrible. Felix Pardin was with us and at one point it was 38 kilos! I spent two and a half years in the workers’ battalions and then I had to do military service in Ferrol for over two years. From 1936 to 1943, I was away from home for eight years.

What do the azadas and the paddles and the peak do?

I had never used piquitos or rifles. I've been in war, but without firing. I have been a privileged one!

Also privileged when it comes to returning?

"After the war was worse for us than the war itself"

No, then no. The lap was frightening. At the University of Deusto jail, I saw my file to the civil guards: “Luis Ortiz de Alfau, disaffection,” and a beetle on top. “Son of Republicans.” I was arrested because I had been faithful to the legal government, because otherwise they had no news about me, because in Hendaia the Falangist took off my suitcase, picked up the clothes and threw the papers. My documentation went away.

Come back.

I went back to Bilbao in late 1943. I looked for needs. My wife made her luggage in a factory and lived in distress. Then, the war had ended, the banks, the city councils, the deputies had no people, and they started asking for workers. But they only took what Franco needed. If you wanted, you asked for a seal like Vertical. I didn't, of course. In this sense, the Uralita factory requested the presence of the operators. They took me the administrator's exam, they went to the trade union section to ask for the label and not, that it was a disaffection and that they wouldn't stick the label to me.

There was no need to do so.

But in the same union, a girl who worked in the office had to hear me how I was denied the certificate and came to me. “Look, the father of this man who is going to give you the seal, has a uniform store on Kolon Larreategi Street, and there you have them all afternoon helping your father.” I mean, I was telling myself that I was out there, it was Casa Manzano. And I went to him, offering him my money. He asked me five thousand pesetas for the seal.

The money is 5,000 pesetas in 1943.

Yes, yes! And I picked up the money, between my relatives and my friends, with a lot of work! It took me two years to pay that debt. I got into the company and started to make a little bit more money. After getting married, we first live in another's house, with the right to cooking. In the kitchen, we would do the food and take it to our room, where we would eat, and we would get into the room. The union building of the house built 20,000 homes in the neighborhood of San Ignacio.

Not for you!

Of course not! The needs of then were for those who made the war with Franco and for them the homes. However, “I have to try!” I told the lady. “You are, you, imbecile,” he told me. But I placed my order. And one day, a man came to his wife's house on the occasion of the request. The woman said: “Don’t waste your time. My man fought with Franco’s opponents in war.” “Look, the other thing, that is to tell the truth. It doesn't happen to me many times. People always want to fool me. Well, this time I have to deceive myself, I will make a report in your favor, so that you have a home.” And they gave us the house. Deputy, civil guard. About us, of night worship. The third is that of the union. The fourth one… And there we live until we retire, without incident, because we had not talked about war. We spend 40 years with our lips tied, mute, expert and silent like fish.

Not now.

No, no more. Now, counting the war, I want to die. The war was bad, all wars are bad, we all made mistakes, but after the war it was worse for us than the war itself. In 40 years, we saw red and black.

Anaiak izan zituen. Anjel –kazetaria, Bilboko udal zinegotzia, Bilbao agerkariaren sortzaile eta Gabriel Arestiren solaskidea–, Rafael –“Errioaren margolaria”, Espainiako akuarela sari nagusia, Salvador Daliren ikasle Cadaquesen (Girona)–, eta Gerardo, Radio Bilbaoko erredaktore 1936ko uztailaren 18an eta Excelsior kirol egunkariko kazetari.

“Suerte handia izan dut, ez dut kirolik ez antzekorik egin, baina optimista izan naiz beti, botila erdi beteta dagoela ikusi dut beti. Bizitzak arazo asko eta bihurriak dakartza, arazoak bata bestearen atzetik, horixe da bizitza, behin ere amaitzen ez den katean, baina behin ere ez dut nik optimismoa galdu”.

Portugaletekoa zuen ama, Zamorako Torokoa aita. Miliziano joan zen gerran, eta frontea ez ezik erbestea, espetxea eta beharginen batailoiak ezagutu zituen. Hangoak amaituta, soldadutzara behartu zuten. Gerra igaroa, gerra ostea bizi izan zuen, 40 urteko diktadura, ezpainak lotuta eduki beharra. Orain, 100 urte betetzera doanean, ez du hura kontatzea beste asmorik. Bizkaiko Elikagaien Bankuan ari da aspaldi, boluntario, administrazio lanetan.

Iazko uztailean, ARGIAren 2.880. zenbakiko orrialdeotan genuen Bego Ariznabarreta Orbea. Bere aitaren gudaritzaz ari zen, eta 1936ko Gerra Zibilean lagun egindako Aking Chan, Xangai brigadista txinatarraz ere mintzatu zitzaigun. Oraindik orain, berriz, Gasteizen hartu ditu... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

1936ko Gerran milaka haurrek Euskal Herria utzi behar izan zuten faxisten bonbetatik ihes egiteko. Frantzia, Katalunia, Belgika, Erresuma Batua, Sobietar Batasuna eta Amerikako herrialdeetara joandako horien historia jasotzeko zeregin erraldoiari ekin dio Intxorta 1937... [+]

Ezpatak, labanak, kaskoak, fusilak, pistolak, kanoiak, munizioak, lehergailuak, uniformeak, armadurak, ezkutuak, babesak, zaldunak, hegazkinak eta tankeak. Han eta hemen, bada jende klase bat historia militarrarekin liluratuta dagoena. Gehien-gehienak, historia-zaleak izaten... [+]

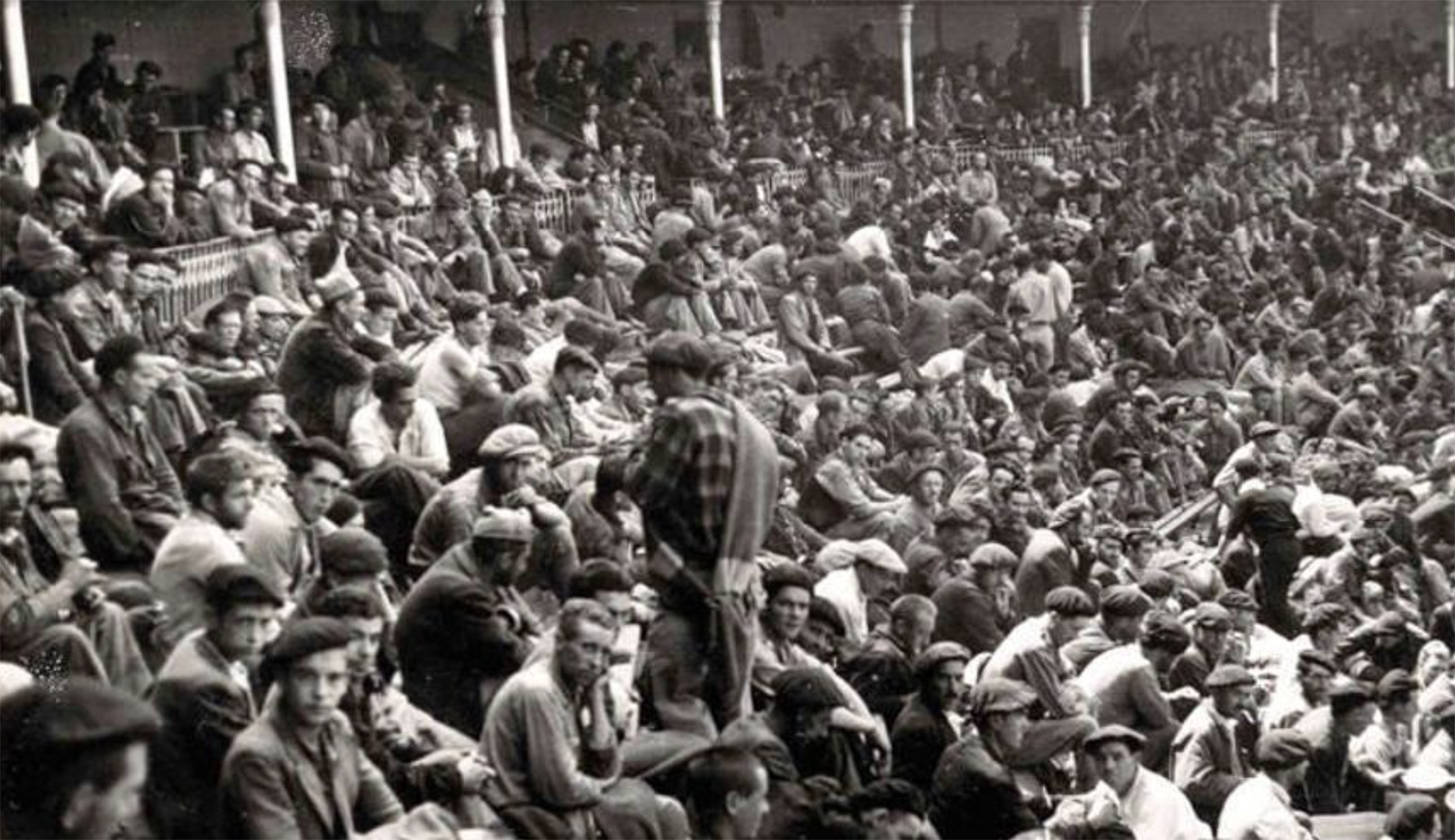

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]