My ‘Smartphone’ leads the poor Chinese poet into the circuits

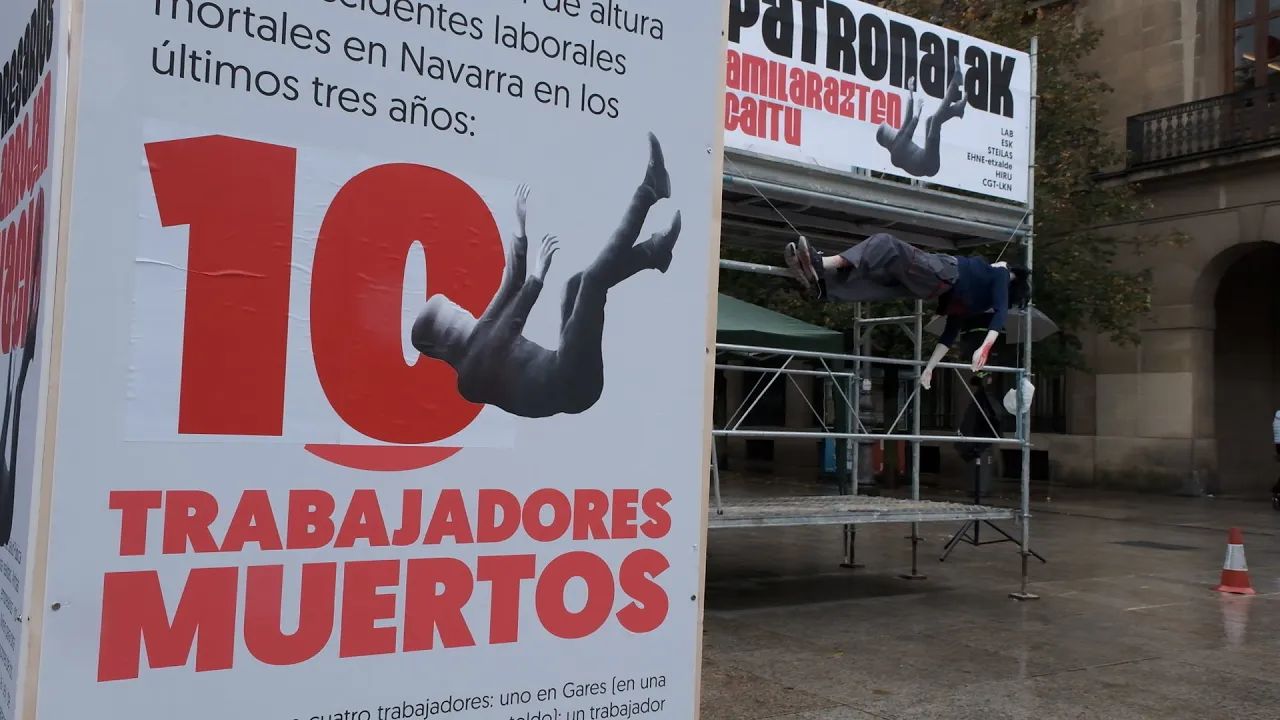

- Most of the new electronic equipment that has become routine with the purchase of Blackberry, iPad, iPhone or Kindle, Apple, Microsoft, Sony, Amazon or Samsung, is made almost with Chinese labor slaves. Now, moreover, they threaten the Chinese workers with the new competition created by the new robots to accept without conflict the oppressive working conditions of the factories.

Xu Lizhi committed suicide at age 24 in the Chinese city of Shenzhen on September 30, 2014. Since Foxconn's dozen and a half suicides since 2010, Lizhi is the best known in the world, as he left his impossible life written in the poem.

I fell asleep standing before the poem that bears the title: “Paper has tarnished me in the eyes. / I have carved with steel pen an irregular black / filled with working words. / Atelier, assembly chain, machine, fichaje card, overtime, salary... / They prepare me to be docile. / I don't know how to scream or rebel, / complain or report. / I only suffer in silence until I burst. / When I arrived here for the first time / I just wanted the gray payroll of the tenth day. / That is why I have chained myself to corners and words, / Renunciation of lack, sickness, my personal problems. / Renunciation of punctuality, renunciation of early march. / For the benefit of the mounting chain I hold as firm as steel and my hands fly. "How many nights have I slept standing?"

Xu Lizhi had come from the camp to Shenzhen, where most of the world’s hyper-modern electronic equipment is produced. I wanted to deal with something related to books, but outside the company Foxconn had found no more than extreme misery. He threw himself out the window of the company's collective bedroom, where he lived during the week.

In the book “La machine est ton seigneur et ton maitre” (Makina da zure jaun eta jabe) they have just collected the experiences of three Foxconn workers. Along with the series of poems by Xu Lizhi, the second testimony is that of Yang, a student who has become a precarious worker.

Third, sociologist and militant Jenny Chan has gathered as Lizhi the hard experience of Tian Yu, a young woman who has gone to work at Foxconn from the field and survived a suicide but paralytic attempt. Chan explains the conditions that have enabled such tragedies: The management system of the giant Foxconn, the complicity of the Chinese State with its employers and the union incapacity.

The stories of Xu Lizhi, Tian Yu or Yang reveal the reverse of the playful and color world of the new technologies that have changed our way of life: the huge, remote factories are exploited by the subcontractors of Appel, Microsoft, Sony, Amazon, Samsung and other big companies in the sector.

In the book's epilogue, the French translator and journalist Celia Izoard has highlighted this schizophrenic aspect of the apologetics of new technologies by comparing "The classe créative des campuses et le zoo des manufactures" with the dreams of California, a mecca of the digital economy and the hell that Chinese workers experience.

Founded in 1974, Foxconn – Hon Hai Precision Industry – employs over one million workers, is the third largest in the world in terms of number of employees and produces half of the planet’s electronics. Foxconn has all the major brands as a customer. In Shenzhen, only in the city of Longhua has 300,000 workers instead of three square kilometers, with salaries up to 500 euros a month.

15 factories, 18 collective room buildings, firefighters and their own TV channels, commercial area... During the 6 days of the week you work here 12 hours a day and the windows of the rooms are protected by iron meshes, since the workers' suicidal noises spread throughout the world.

Better a robot than a human slave

In California, on the Google-based Mountain View campus, brainstormings are made in a pool filled with plastic balls. Gyms open day and night. 30 restaurants, all free... for elite employees who also earn 100,000 euros a year.

This is compost with organic waste, food is bio, there's no fish getting fatter in the nurseries -- in the stories of Apple or the privileged workers of other Silicon Valley corporations, the new culture of work that has been created around the hackers hitting ohr, a liberating technology that is said to be connecting a new world.

China, which has been engaged in electronics production since 1980, has not been very concerned about the lives of its workers until 2006. How about that 30-year indifference? According to Celia Izoard, as campuses and R&D laboratories multiplied in the West, the rich countries were sitting in the production of knowledge and in the exchange of information, the high-level technology at their center dematerialized through an ideological-magical operation.

“The invisibility of the material consequences of a materialistic society,” says Izoard: “The work at the factory and in the chain has never been as far from the imaginary of the globalized middle classes as it is now, despite the fact that there are more factories in the world than ever and in the chain more workers work than ever before.”

Because of the poor relationship we have with technology, we're not aware of its effects globally. “Engineers, entrepreneurs and communicators show with great imagination the advantages of this or other technology. (...) But they do not show any imagination when comparing the social benefits they announce with the human and ecological costs of new electronic objects.”

Foxconn’s president, oligarca Terry Tai-ming Gou, 84 on the list of the world’s richest people, invited the director of the Taipei zoo in 2012 to give a lecture on the corporation’s main paintings on animal treatment. Lehendakari said that "one million people were fed up being the head of the animals." It's not a trivial anecdote, because Gou has announced that he wants to eliminate as much as possible human workers, replacing them with robots.

Izoard notes that in 1949, the cybernetic founder, Norbert Wiener, alerted the leaders of the U.S. majority union about the risks of automation processes: “Any working hand, if it concurs with a slave, whether a man or a machine, is condemned to withstand the slave’s working conditions.” In Hipster's golden times there are not many such announcements.

In China, there are certainly strikes and clashes between the workers, but Izoard sees the ability to cope with the situation of the globalised middle classes. It requires an effort of imagination: “What if we restarted all the infrastructures needed to produce all the computers, TVs, iPad, photographic machines and TVs we use in our territory?”