"The struggle of women during the war has been a total resistance"

- On 10 December, International Human Rights Day, an event was held at the seat of the Presidency of Vitoria-Gasteiz on the occasion of the René Cassin Prize. The Basque Platform of Complaint against the crimes of Franco is awarded in this edition. They've brought four people on the stage. Among those involved is Julia Monge Sarabia.

You are preparing the exhibition in the society Intxorta 1937.

Yes. Last year we paid tribute to the Gudaris and militiamen in Elgeta in April. Unexpectedly, we relate to a Chilean, Mauro Saravia. He, the surviving soldiers and militiamen, were at a standstill with the aim of taking pictures. We, on the other hand, engaged in talks between the soldiers and the militiamen. We thought about joining our forces, and we did. We have come to the Bizkaia General Meetings, we have been with Ana Otadui, they have explained our intention and they have given us a little help. Now, at the beginning of March, we will have an exhibition in Bilbao and then it will be displayed elsewhere. The exhibition will be supplemented by short photographs and biographies of 27 people each. This year, on the other hand, we will pay tribute to women, we are collecting their testimonies, photographing them, so that next year we can make an exhibition dedicated to them.

The documentary you made in 2012 is not a difficult starting point: “Arrasate 1936: woman, war and repression”.

In addition to Arrasate, we have also made documentaries in Bergara, Aretxabaleta and Oñati. Also another one that relates to Intxorta in general. What happens is that the task of men is much more spectacular: the battalion and the company of the other, in the war struggle. The struggle of women was not the same, but the struggle continued. That is what we are going to say this year in Elgeta. As some of the women we want to pay tribute are dead, they will receive tribute through their relatives.

Of course, older people.

Of course, yes! The other day we were in Toulouse talking to a woman. It's called Teresa Nadal. His father was socialist and the councillor of the City Council of Bilbao before the war. After the 1934 revolution, he was captured. When her father was in jail, in 1935 Teresa began studying Medicine in Zaragoza. There were over a hundred students and only three women. Do the first course, return on holiday to Bilbao and in July, the war. He didn't come back to Zaragoza. The war, and the father was taken out of jail with the amnesty law. Teresa, for her part, volunteered as a nurse. She said to us: “I did the first year of medicine, but I didn’t know anything about medicine!” A field hospital was set up in the bullring in Bilbao and there was Teresa, along with other colleagues, in the operating room. According to him, the seriously wounded and the “significant” people brought her there. When Bilbao fell, to Santander Teresa, with her parents. From there to France, then to Catalonia and then to France. And he knew who was going to be his husband, who had fled the Germans.

Both Teresa and man fled war.

So Alberto, the son of Teresa, spoke. He speaks perfectly in Spanish because his mother educated them in Spanish, trusting that they would soon return to this match. He has always lived in France.

Odyssey.

Well, they went from France to Morocco for work reasons. From there to Algeria, where they were captured by the local war. The children also grew up in learning age, but they couldn't learn anything, so they decided to go back to France. Teresa, 98, has the idea of going to the tribute that was given to her in Elgeta.

This year you bring the woman to the foreground in Elgeta.

That's our intention, to bring it to the foreground. “We have done nothing!” How many times we have to listen! On other occasions, they bear testimony from another person, not counting what they suffered, or without giving it importance. It is true that some lost their father or brother in the war in front of them, but the consequences of their death were received by themselves, the survivors. However, they value the others rather than the same. It's terrible that nobody comes home, takes his father, takes him to the cemetery and kills him against the wall, but the stigma of the survivors is there. “The lady of the red… the sons of the reds…”. And of course, I couldn't say anything. In silence, the children went ahead and ran out. When they count, they tell the others, what happened to the others, rather than what they suffered.

Some people don't want to count.

It has happened to us on more than one occasion. Sometimes, the time to collect the testimony is agreed and, at the last minute, the testimony is rejected. I remember one case where my wife said yes, she would tell you what she had lived and her son's illusion. “He’s kept them very quiet, and now, almost 100 years, and he’s going to tell them. It gives me joy.” The day before, the woman got sick, got in her head, and… she didn’t tell. In these cases, we always respect the decision of others, despite the testimony lost. Some have always told the past. Others have had taboo. And there are those who start to tell it older. This is the case of Teresa Nadal. His son Alberto told us: “Our mother just started telling them back then.”

What is the receiver's attitude? Do you take account of the testimonial words of the elderly?

In 2012, when we made the documentary about the women of Arrasate, we made the presentation at the Amaia Theater -- first, the screening in Basque; then the tribute; then, the Spanish version -- people were very excited. But we realize that young people, in general, don't give it enough importance. “The old stories of grandparents!”, say. Something like disrepute. We don't realize that they were real facts, a real break. If the Republic ' s educational model had advanced, for example, we would be much better than we are now. We've been standing there for 40 years, with no chance of doing anything. It was one of the questions we asked in the documentary: “What are you going to do to young people?”

And what?

Everyone agreed. “You have to know. Some believe it has not been ‘for so much’, but it was ‘for so much and more’.

We met you when they delivered the René Cassin awards. When it comes to collecting the prize, you, along with Josefa Berasategi, Luis Ortiz Alfau and Josu Ibargutxi, speak on your own behalf and the Basque Platform. After the words of the political leaders, the first question the presenter asked was to you: “At what time is the complaint?” I would like to know.

The Basque Platform started in 2009 and is working within the National Association of Associations of the Spanish State. The 1977 Amnesty Act prevents the investigation of the crimes of Franco, the crimes of torture, enforced disappearances, the executions summary... However, the UN Commission on Human Rights, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have accused Franco’s crimes against humanity and say that they are not prescribed, have made a number of recommendations to the Spanish Government, but this excuses the 1977 Amnesty Act. This law is a wall. In fact, the complaint began in Argentina, following the complaint of Dario Rivas and Inés García Holgado, and at the moment there are about 130 plaintiffs in Euskal Herria. These are older people, who are not in a position to enter an airplane to Buenos Aires and testify before Judge Servini. Some have declared themselves here either by request or by videoconference. In October 2014, the Buenos Aires court charged 20 people, but the Spanish Government has done nothing but obstruct them, pushing for the complaint not to flourish. We only have to ask for Universal Justice, because only with the support of the International Jurisdiction can crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity be investigated and judged, because Universal Justice is above the laws of a State. The next step of the platform will be to try to make municipalities crackers. We have started to meet, we believe they have to denounce what happened in towns and cities through grievance. Memory associations have data. The involvement of the institutions is mandatory. That's where we are. The last thing I have known is that in Mexico another man has also filed a complaint.

Some representatives have joined the complaint and others have not moved. He didn't want to.

You may think that the complaint will not go ahead, that nothing will come from there, that it is impossible… We know from the beginning that it is difficult, long-distance, that you may not see the light, but what says the lawyer Carlos Slepoy [Argentine lawyer who directs in Spain the issues affecting the complaint]: “In Argentina, we also believed that it was impossible to reverse the Law of the Last Point, but we did.” In Argentina, one thing favored them: it was a few years since the crimes were committed until people started moving. The culprits were alive. But here, many years have passed and many of the culprits have died.

Dead and alive. At the session of Lehendakaritza Josefa Berasategi and Luis Ortiz Alfau told their truth. What's your truth, Julia Monge Sarabia?

To begin with, I entered society Intxorta 1937 knowing some things about my history, that my parents and grandmothers had gone into exile, and back they ran out of work. For example, his father was taken abroad at the age of seven. By then, the father had already disappeared. Grandma made her accustomed journey: They left Mondragon, went to France, then to Catalonia and returned to Mondragon, but returned to the town and were expelled from the work of [Union] Cerrajera. Grandma worked as a midwife, she was very skilled. Back, her mother died her seven-year-old daughter, and she also got sick and died shortly afterwards. My father and his sister were alive. Of course, I didn't know grandma, and my grandmother's aunt, Ursi, has given me as a mother. The fairy, Ursi, was the one who counted things, but then I didn't listen to him. Now I say to myself: “If I was alive!”

The story of your family.

I've always been aware of how women went through war and post-war. Her parents and grandmothers came from San Román de Hornija (Valladolid, Spain) to Vitoria-Gasteiz. I am sure they would be poorer than poor. Marry in Vitoria, make three children, and then war. Bilbao, Santander, France, Tarrasate (Catalonia) and Aretxabaleta. If they knew what I am doing now, collecting the testimonies of the people who suffered the war!

You've ever been presented as an activist.

Activist me? He's going to be working to have been in feminism! And when working the historical memory, you also have to bear in mind that the woman stays apart. “We’re talking for everyone,” some say, but I don’t think it’s enough. The struggle of women in the time of war has been completely different, has nothing to do with the struggle of man, but it has been a struggle: survival, total resistance. We've been to Elgeta many times, fixing the trench, when everything was scrambled. The Elgeta City Hall decided to clean some of the material inside. Once we went to Intxorta, we had snow, fine wind, cold… we spent the morning and back I told them: "If war comes back, I'm the phone call. I am not old enough to walk in trench! Ja, ja…”. No doubt death was very hard, but in the meantime, where were the women, what did they do? It is necessary to ask, to count that part of the women, but it must be told. I think we have to treat it exactly the same way. n

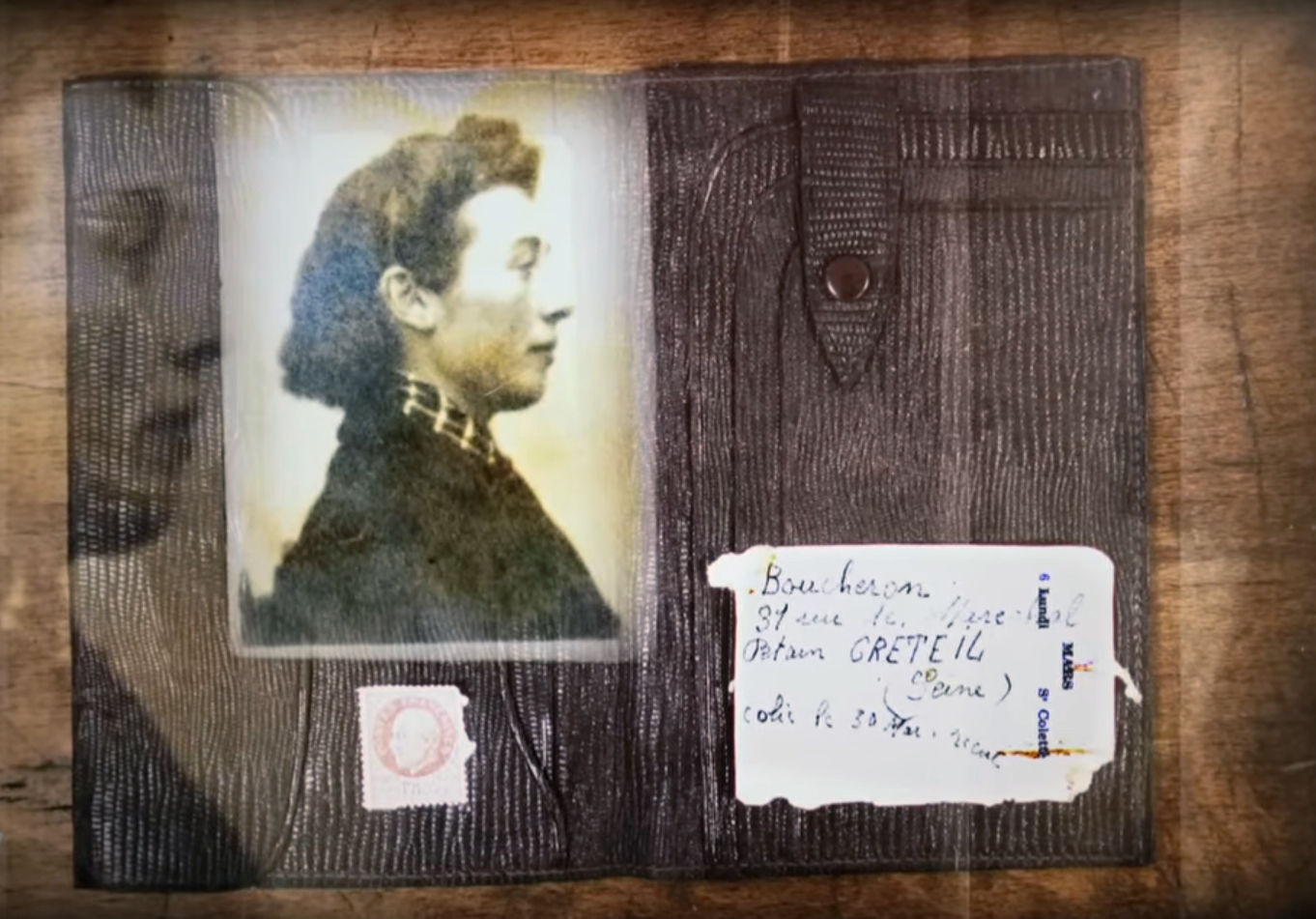

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

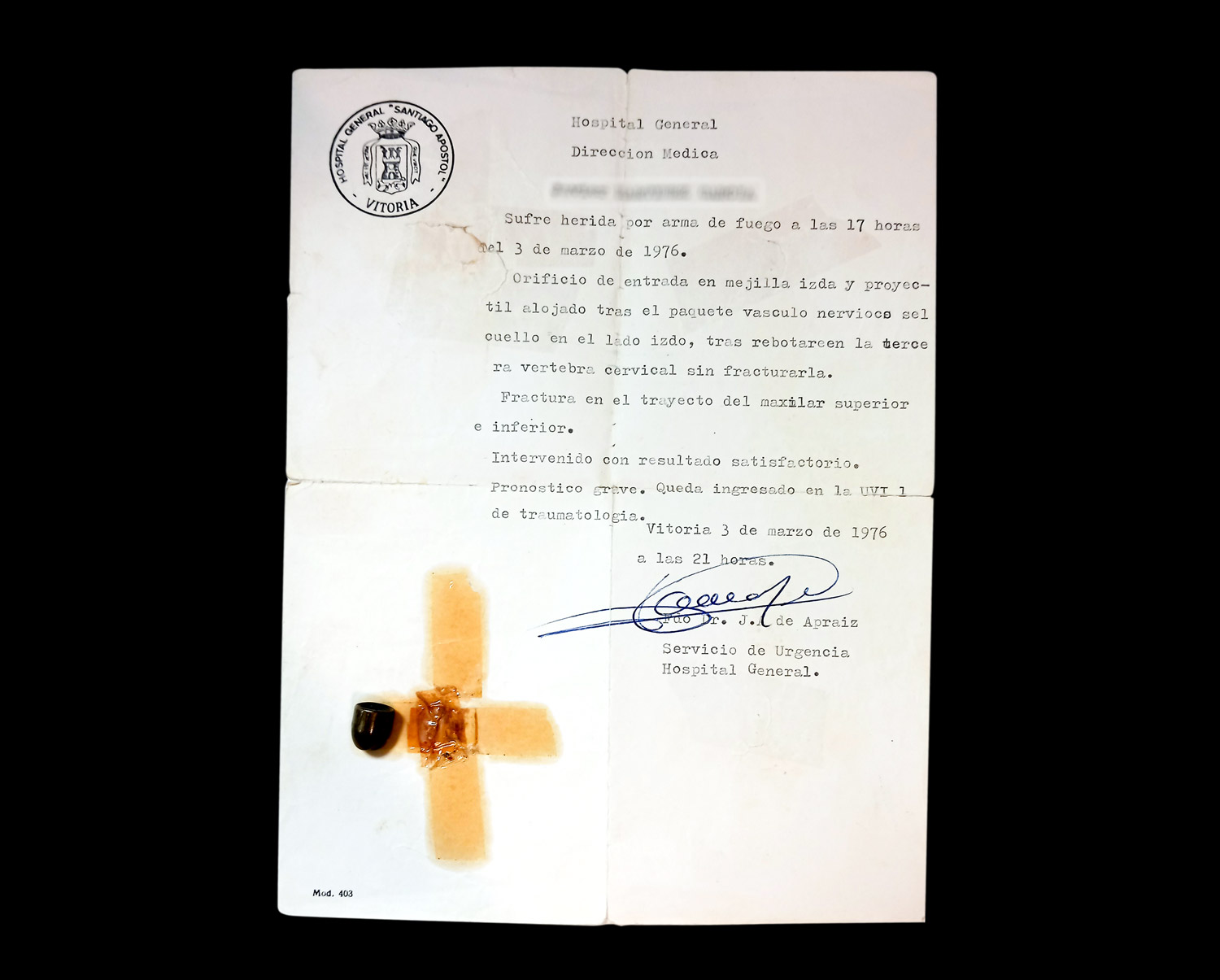

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.