The novels were pacifist enough for the Nazis to burn in the fire.

- The First World War left a great wound in German society and a taboo: failure. In this regard, some “myths” emerged, especially those that said that Germany was defeated by betrayal in the field of fire and not in diplomacy, but the war failure was a subject that had to be avoided in the literature. But war doesn't. The Weimar Republic emerged from the war and, wanting to give or take away meaning to a recent past or to a new political system, the debate and interpretation of the war became a stage of struggle during the years that elapse from the end of the First World War until the triumph of Nazism. This ideological and aesthetic struggle took place mainly in the literature.

“Every night I enter the trenches to mutilate and kill people”

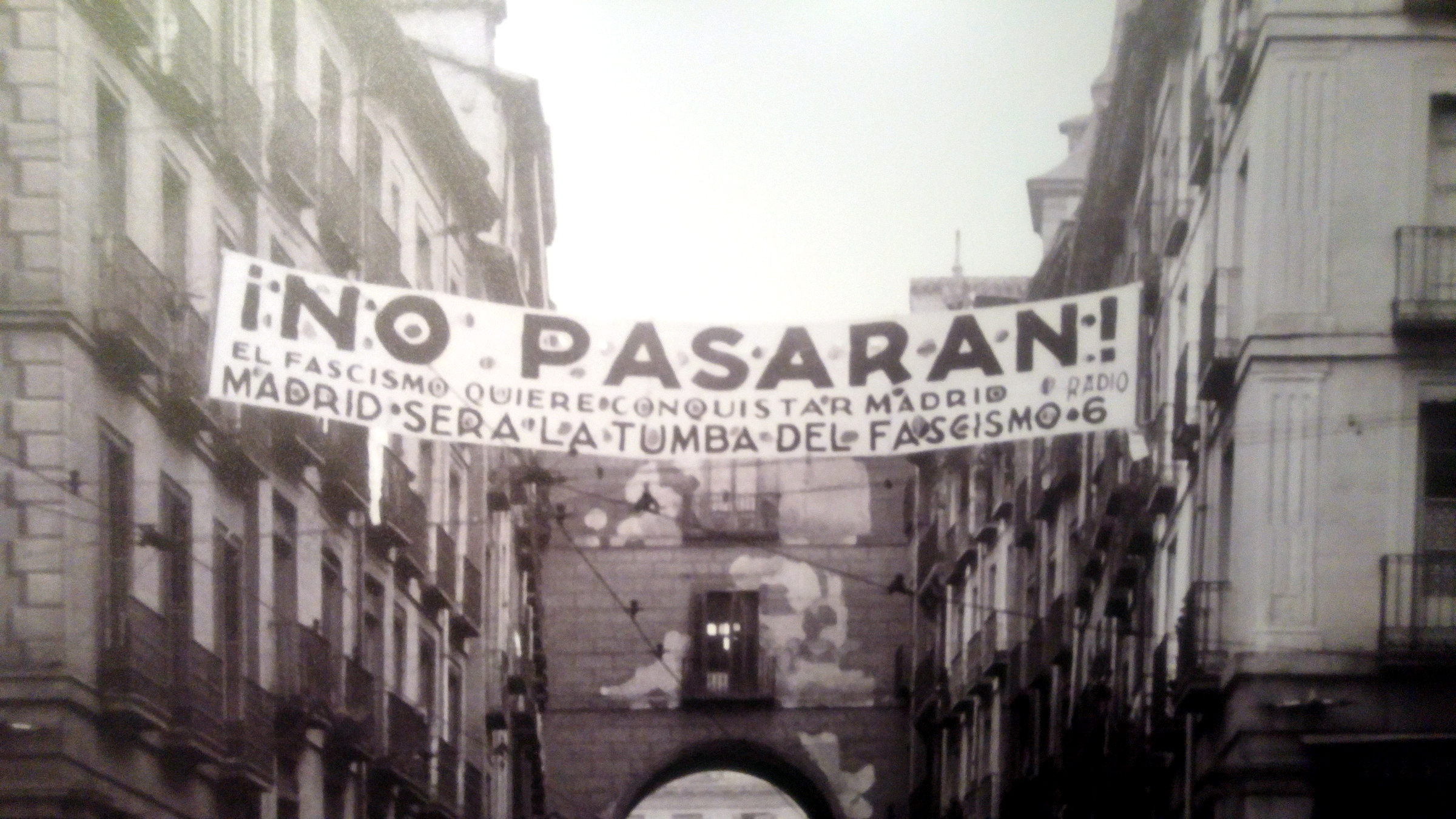

“War is the greatest misfortune that can happen to a people, whether it is victor or loser, and whoever acts instead for peace is in favor of the homeland.” This is stated by Engelbert Winz in his travel book Neues und Altes aus dem West (Old and new news from the Western Front). In this pacifist book which refers in the title to the well-known novel Im West nichts Neues (with no news in the West) by Erich Maria Remarque, on his journey through the former front of France and Belgium, the author collects memories of war and descriptions of places of war, while recounting the encounters with his former enemy. Winzen, it would have been a residual anti-war text: Published in 1932, shortly after, in May 1933, the Nazis threw a large number of books into the fire, among them many novels with a critical view of the First World War, thus ending a long battle. Since the arms were silent, there was another battle in the literature of the Weimar Republic to interpret and value that great war.

In Germany in the 1920s, literature was in charge of reflecting on war, much earlier than history.

Historian Modris Eksteins states that literature was in charge of reflecting on the war in Germany in the 1920s, at a time earlier than history. It is not a new idea, since in the 1920s the critic Theodor Heuss underlined the same in a comment: The novel by Ludwig Renn Krieg (Guerra) and the novel by Remarque were as important as any collection of historical documents, as both were historical documents, witnesses of war.

Often, at the starting point of the books on war, there was a need to internalize, cultivate and somehow express the personal traumatic experience of that new war: “Since October I’ve been a patrol officer. That means that every night, with a group of men, I get into the trenches of the English to kill and mutilate people,” wrote Peter Suhrkamp, who later became editor; “For the moment we are calm [...]. Despite continuous fire all day long and three gas attacks, our nerves are in shape. Basically, I've experienced a gas attack -- three, better said. It hasn’t been so much,” Ernst Jünger wrote to her parents in June 1916. All of them, of course, did not have the Jünger phlegm and there were very different interpretations of the war.

Old moulds for a new war

In the early years after the end of the war, and even before the end of the war, several authors, following a classic model of heroism, tried to imagine war as an adventure. To this end, the autobiographical narratives of the submarine officers or the stories of the aviators who had participated in the celestial battles were particularly appropriate – but the trench war did not give rise to the epic. Despite its cruelty, war is a duel between gentlemen in some books (there is no lack, for example, of the narration of the official submarine that saved some Englishmen who died at sea after the shipwreck of an enemy ship), and it is also an opportunity to be impressed by the danger, from many points of view: “It’s an exciting moment when you fly to the enemy, when you see the enemy but you still have a few minutes before attacking him. I think I was getting a little pale on those occasions, but unfortunately, I never took a mirror on top of it. It’s a good time, because it’s very exciting, and I love it,” wrote Manfred von Richthofen, the famous red baron, in his memoirs.

Ernst Jünger will turn this passion for danger into an anthropological principle: “Each era has its work, its obligations and its pleasures, and each era has its own adventures. [...] Work is life, but adventure is poetry. Duty helps to cope with work, but the passion for risk makes it easy. That’s why we unashamedly accept that we are adventurers.” To a large extent, however, Jünger’s In Stahlgewittern (Steel Storms) is an exception among all these first hour books: on the one hand, even if he follows the model of elite officer, the description of his war is more realistic than that of officers of submarinists or aircraft, and on the other hand, his approach to action, danger and instinct, which becomes the beast.

“Compared to him, all that has been done so far is faulty work”

Kakotx's words are from the writer Carl Zuckmayer, who deals with the novel No news in the West of Remarque. Remarque’s book is a milestone in Weimar’s war literature, but before this novel was published it would become a bestseller, the number of anti-war books was not small: Ludwig Renn – Krieg (War) – Arnold Zweig – Der Streit um den Sergeanten Grischa (debate on Sergeant Grischa) – Ernst Gläser – Jahrgang 1902 (1902 generation) – Ernst Johannsen – Vier von der Infe (four) infantas.

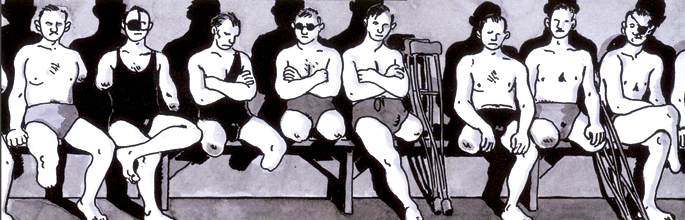

The anti-war literature emphasized cruelty and opposed the classic adventurous hero to a soldier turned zombie. In books that have a critical attitude to war, a crude and realistic description of suffering is common, in which places of literature on the surface of war become prominent, such as hospitals or mental hospitals. Loco or herbala: soldiers, mind or body destroyed by war, has lost the opportunity to reintegrate into post-war society, it is a waste with no future. This human landscape also appears in the painting of the time, in works like George Grosz or Otto Dix.

Realism often becomes grotesque and dwarfs in black humor: Leonhard Frank, in his novel Der Mensch ist gut (Man is good), describes a soldier asking for prayer and grudge on his leg that they have just amputated – coming down from his thigh; when they have brought it, he has held it in his arms, he has caressed it and, all of a sudden, he has torn it down with a gesture of repugnance: “That’s not my leg”; “it wasn’t your leg. The nurse, exhausted, had taken a wrong leg out of the boat.”

War creates zombies: we see that in the books of Remarque or Renne, soldiers without thoughts and feelings that fulfill their duty as machines.

War creates zombies: we see that in the books of Remarque or Renne, soldiers without thoughts and feelings that fulfill their duty as machines. That is precisely what this anti-terrorist literature has been accused of not showing any way out, of exhausting itself in despair, never in the throes. Ludwig Renne’s novel, for example, “is the epic of the soldiers’ small duties,” – as critics Theodor Heuss said in 1929 – “everything is so obvious that soldiers give up discussing or reflecting on war and its meaning – it does not work, because nothing will change.”

“Wars don’t feel destroyed, wars feel purified”

In the Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter in Munich, Erich Limpach criticized all pacifist novels, in short, the most important ones, also the author of a war novel. After Remarque's novel, there were many imitations, plagiarism, parodies and criticism for and against. In 1929, when no news was published in the West, there was also the economic crisis and, later, the Nazi upsurge. Along with the literature against war, a new literature in favor of war was also published at the end of the 1920s and early 1930s. In view of the pacifist literature that “insulted the feelings of millions of citizens” – once again the words of Erich Limpach – the new literature, without denying or concealing the cruelty and brutality of war, considered war conflicts necessary and gave the enemy increasingly accurate features.

After Remarque's book, in the first three years of the 1930s, its success will not be repeated again: the political atmosphere did not help, on the one hand, and, on the other, most intellectuals who considered the commercial genre as a result of Remarque's success. Heroes or zombies? Futureless waste or fire-recovered patterns? In May 1933, all the books that compromised the sense of war were included in the list of those who should calcinate, ending the discussion.

And the war brought a bestseller.

Erich Maria Remarque Al Oeste no news

Between the two world wars there were many novels of war that were published in Germany; Jörg Lehmann, author of the book Imaginäre Schlachtfelder (His imaginary fields), who investigates the war literature of the time, counts more than 600 numbers of specimens that could be suitable for his investigation. Some were very successful, others not so successful, but above all it became one of the best-selling German books of all time: Im West nichts Neues by Erich Maria Remarque (No news in the West). Published in 1929, the novel sparked heated debate in the press of the time and immediately became the symbol of anti-terrorist literature, as it gathered “the truth” about war. But things were a little bit more complicated.

Erich Maria Remarque was founded in 1898 in Osnabrück. In 1921 he changed his name from Remark to Remarque, under the pretext of the French origin of his father's family, and by the way he replaced the central name with a more elegant Mary, with which he left over and with his mother's surname he would complete the grace of the protagonist of the novel not new in the West: Paul Bäumer. However, the novel is not autobiographical: Unlike Bäumer, Remarque did not volunteer in 1914 – it would have been impossible, he was sixteen years old – he was called to the army in 1916 and, after a month, he was seriously injured on the forehead – due to the wounds he received in other hands, he had to leave his musical career.

After the war, prior to the publication of the novel that would give him fame, he had written three books, two of them published, had worked as a journalist in various newspapers and exchanged letters with great writers of the time. In the advertising of novel, Ullstein’s editorial presented Remarque as follows: “Erich Maria Remarque is not a professional writer, he is a 30-year-old who felt a few months ago the need to put in words what happened to him in the war to shape that experience.” With the help of the author himself, the editorial wanted to sell the book, that is, as a true report on war, prepared by an inexperienced young man representing all the anonymous soldiers killed in battle, in no case a writer; the naive result of having suddenly felt the need to overcome the trauma of war, and not the fruit of a literary intention.

In 1929, when 'There's No News in the West' was published, there was also the economic crisis and later the Nazi boom.

Without denying its quality, the lack of news in the West, as researcher Thomas Schneider has shown, is also the result of a marketing campaign. During his stay at a war hospital, Remarque had the first idea of writing a novel about war, and for that he went through several stories about war. The manuscript was approved by the editorial Ullstein in 1928, but before publishing it underwent a long editing process, which aimed to depoliticize the novel as much as possible. The harshest criticism of the war and its consequences remained on the way.

However, as soon as it was published, the book was very successful: Published in January 1929, a hundred thousand copies were sold in February, half a million were reached in May and 900,000 were reached in December. Translations also came quickly – in France, in England, in EE.UU. ; in Basque, incidentally, we still do not have this novel, nor anything else Remarque: On Susa's web, at least, there's no trace of it.

In Germany, also in Austria, the book brought controversy in the press; in addition, the controversy often focused on the writer's biography, as the publisher presented the story of a naive soldier novel. The political right strongly contested the pacifism that emanated from the book and described as anti-German the criticism of the novel to war; there were also criticisms from the left, especially because the author refused to participate in the controversy that had arisen around the book: it was considered apolitical.

There were also answers in the literature. Some of them tried to harness the success of the news in the West for their benefit: for example, Carl A. Dr. G. Otto, with the novel Im Osten nichts Neues (East without news). There were also parodies, such as Vor Troja nichts Neues (There are no news in front of the line), published with the pseudonym of Emil Marius Requark and situated in the Trojan War, as well as serious and humbling that show their indignation from the title: Im West doch Neues by Eugen Erbelding (There's news in the West), or Im West viel Neues by Richard Kroener (There's a lot of news in the West).

In May 1933, all the books that compromised the sense of war were included in the list of those that should calcinate: the literary discussions ended

After the book, the film version was released in the United States in 1930: In Germany, the Nazis, increasingly influential, managed to ban the film – although the ban was annulled in 1931 –; in Austria it was also banned, but the ban was officially maintained until the early 1980s.

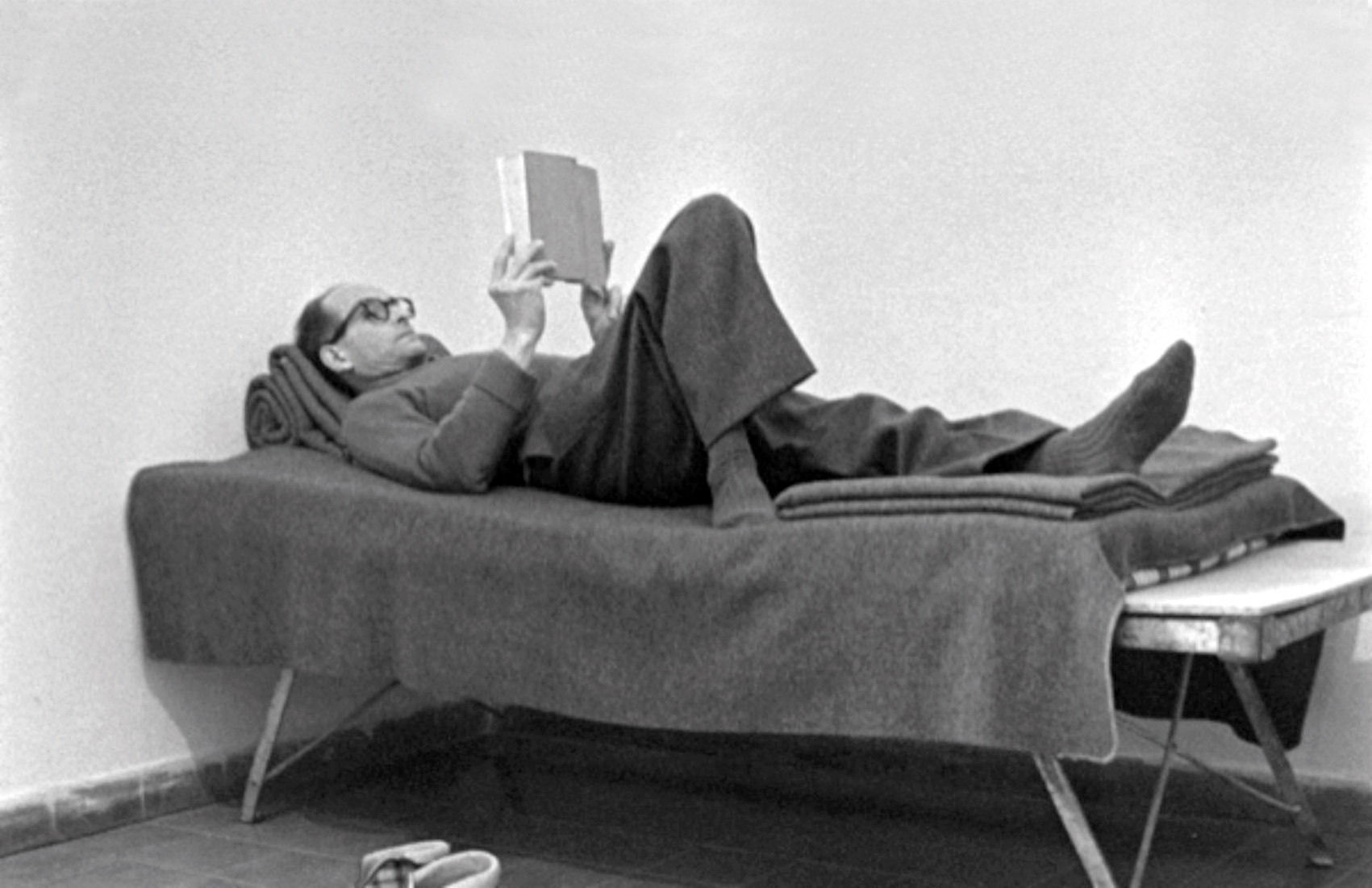

Of course, there was no news in the West, it was on the list of books that had to be thrown on fire, and the author was one of the most hated by the Nazis. In 1933, in the year Hitler came to power, Remarque departed to Switzerland and, later, to the United States. The success of his novel has led him to never have problems with money, as the journalist Volker Weidemann explains, to find with difficulty a German writer who has had such a glamorous life as Remarque's. However, the journal he wrote in America gives us another image. At the age of forty he wrote: “Forty years. That lasts ten years longer than thirty-nine. A life in vain. I turned on the gramophone. I took a photograph of the room. Like I didn't come back. All as if it were the last time: summer;– house;– peace;– happiness;– Europe;– the same life, perhaps”. Remarque's biography, written by Wilhelm von Sternburg, is titled as if it were the last time.

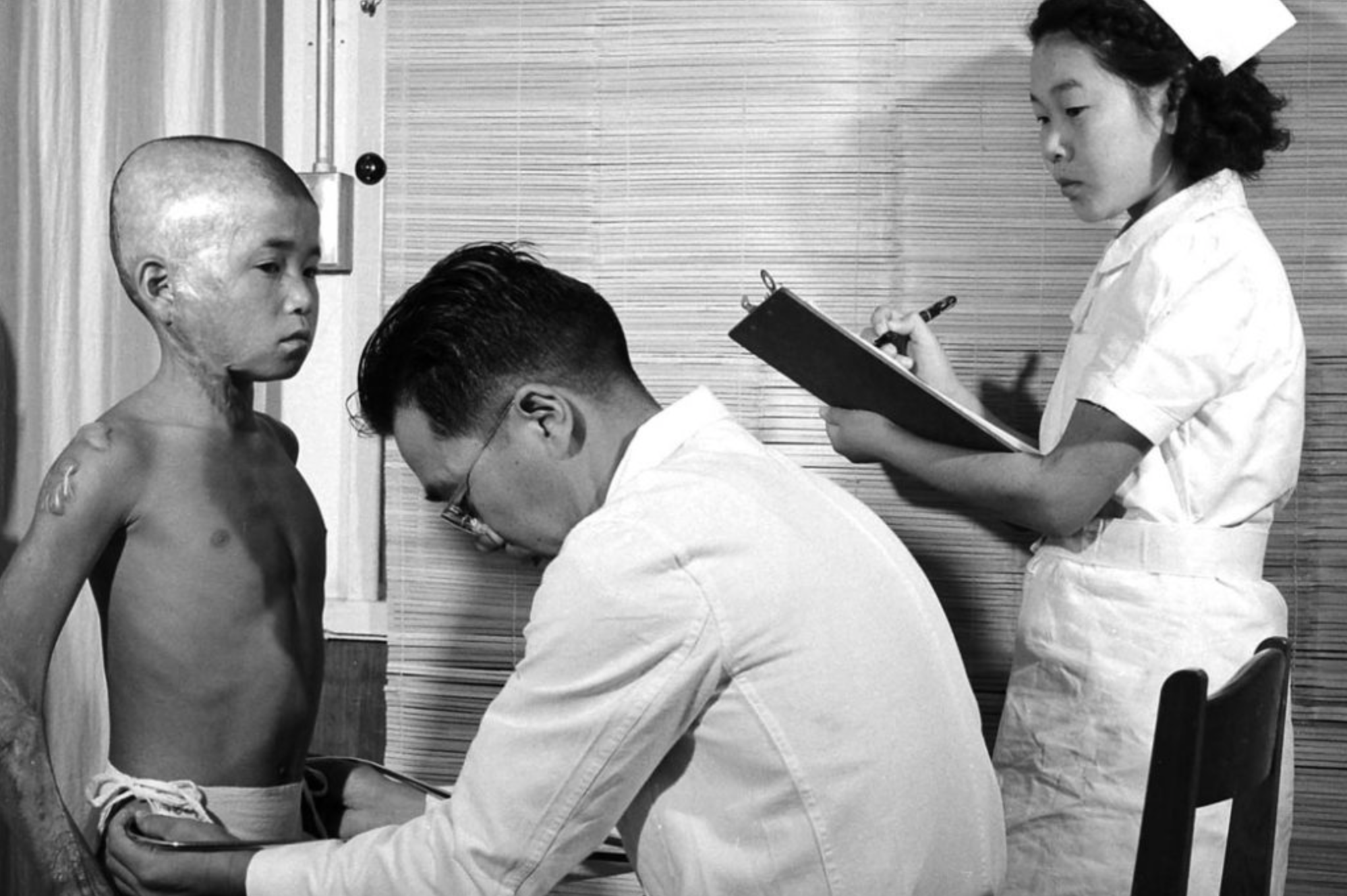

Japan, 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States launched an atomic bomb causing tens of thousands of deaths in Hiroshima and Nagasaki; although there are no precise figures, the most cautious estimates indicate that at least 210,000 people died at the end of that year. But in... [+]

Born 27 June 1944. The German soldiers carried out a raid on a small town of about 80 inhabitants of Zuberoa. Eight people died on the spot and nineteen were arrested, all civilians, nine of whom would be deported and only two would survive from the concentration camps in which... [+]

Normandy. 6 June 1944. They started operation Overlord: Thousands of British, American and Canadian soldiers landed on the beaches of Normandy to drastically change the course of the Second World War and, therefore, history. Or at least that's what we've been told a few days ago,... [+]

Genocide is unfortunately a fashionable word. According to Rafael Lemkin’s definition in 1946, genocide is defined as “actions aimed at the total or partial destruction of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.” These actions may include “killing the members of... [+]

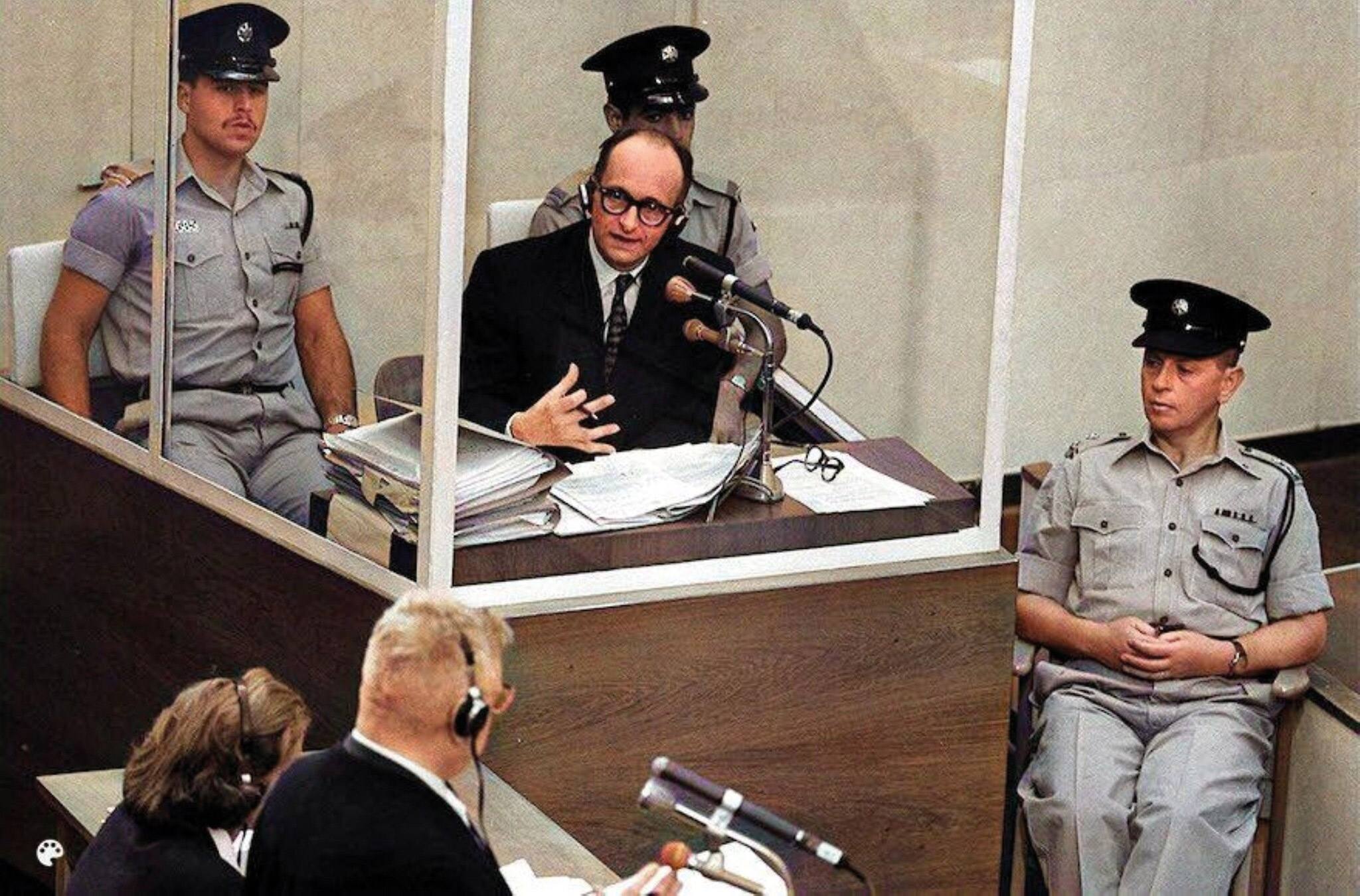

Karl Adolf Eichmann (Solingen, Imperio alemán, 1906 - Ramdel, Israel, 1962) foi o oficial superior das SS da Alemaña nazi, especialmente coñecido polo seu nomeamento como “responsable loxístico” da chamada Última Solución ou Última Solución. A planificación do... [+]