Disagreement between the public and concerted school

- In 1993, the Basque Government launched the Basque Public School Law, with two main objectives: the reform of the public school and the integration of the ikastolas into the public network. As a result, many ikastolas decided to publish. Currently, 50% of the educational network in the CAPV are public centers and 50% are concerted or concerted – mainly ikastolas and Christian schools. The Basque Government has now begun the final phase of the Heziberri plan: Creation of a new education law for the CAPV. Previously, Heziberri has defined the management, autonomy and financing of educational centers, the pedagogical framework and the curriculum, and has included everything in the decrees. The Basque Government affirms that the next law aims to “adapt to the new times and build its own educational system” and also aims to integrate the three main networks of the CAV: the one now the Law of the Basque Public School, will become a law of the Basque School, which affects not only the public network, but also the concerted network. The Minister of Education, Cristina Uriarte, has started to meet with the agents to discuss the differences and objectives that have emerged between them, and around the table, Abel Ariznabarreta, member of Ikastolen Elkartea, Aitor Idigoras, professor of the public school and the pedagogue Mariam Bilbatua.

Is the Basque Public School Act of 1993 exhausted?

Abel Ariznabarreta: First of all, I should like to thank the Basque Government for putting the issue of the education law on the table, because we see that it is given a literal priority from the Basque Government’s Department of Education, but in practice we never came to lay the foundations of a law, and on this occasion I also have doubts that in the coming months we will be able to do what has not been done in the previous three and a half years. In any case, we educational agents have made our contributions over these years, which can serve the law.

In reply to the question, the 1993 Act was carried out as a result of the school or political pact that was held in 1992 and, if I am not mistaken, the pact was planned for five years. Well, since then we have continued with the same inertia law and in 22 years many things have happened: we are in the knowledge and innovation society, great technological changes have taken place and there are other demands. To this must be added that we have also had six or seven organic laws, basic laws that the State has imposed on us and that are obligatory to comply (because they affect the entire State above the autonomic scheme). Although the Statute of Autonomy recognises the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country full competence in the field of education, it has become clear that any Spanish organic law is above the CAPV’s own laws, and we have had about six (the last example is LOMCE), so I am thinking of the distortion that the Basque Public School Act of 93 has suffered. Moreover, although the Law of 93 provided for some beneficial elements for our educational system (such as the autonomy of schools), they have never been implemented. For all these reasons, we have long advocated the need for a school pact and a new law.

Aitor Idigoras: Yes, the Law of 93 is obsolete, but there are details that are being presented as novel and that can be done with the Law of 93: for example, the Minister of Education, Cristina Uriarte, is now talking about including more hours of Basque in model A, but that is a proposal from a long time ago and can be done with the Law of 93. The same thing that Abel mentions the issue of the autonomy of the centers, included in the Law of 93, but not developed. In other words, some sections of the Basque Public School Act are very obsolete, but others are about to develop them. But the question is another: we will move from the Basque Public School Act to the Basque Education Act. The public word will disappear; following the neoliberal trend of the last twenty years, it is intended to change the management of educational networks. Heziberri has three phases: the pedagogical framework, the curricular project and the law we are talking about today. The first two phases are approved, and in the second, not only on the curriculum, but on the management of networks, autonomy, the treatment of languages… very controversial things are said, so, although we must overcome the Law of 93, we must be careful where we are going. Are we going to put the concerted centres, the private centres and the public centres at the same level as Heziberri does? Heziberri’s presentation literally reads as follows: “The objective of the Heziberri 2020 plan is clear: Bringing together the lines of innovation and development set out in the European Framework for Education and Training for 2020 with the challenges of education in our context and environment (…) In drawing up this Plan we have taken into account three sources: mainly the European Union’s education objectives for 2020”. And what are those goals? I will also read them literally, those established by the European Commission in 2012: "The youth unemployment rate is close to 23% across the European Union, but there are 2 million jobs that cannot be filled. Europe needs a radical rethink of how the education system can provide the skills the labour market needs.” That is the European framework and that is the reference framework of Heziberri. Heziberri is nothing to deal with LOMCE, the objective is the European strategy, because the way to understand education is the same.

Mariam Bilbatua: The Law of the Basque Public School attempted to respond to a situation that had already come. In the transition, on the one hand, in our educational system there were ikastolas that worked a lot in the process of Euskaldunization, in the transmission of Basque culture and in the construction of our educational model. On the other hand, with the approval of the Gernika Statute, the Basque Government was made with public schools, which until then had contributed very little to the Basque Country and to the transmission of Basque culture. The development of both networks since 1979 required its own law: the ikastolas needed an institutional recognition that would guarantee the future of the project developed until then, and the public schools, a recognition of the steps taken in the process of euskaldunization and transmission of the Basque culture. Today, the public school is recognized for this contribution in Euskaldunization and transmission, but I believe that the institutional recognition needed by the ikastolas has been suspended. In this respect, I believe that the Law of 93 did not fulfil its duties. In addition, the criteria that were considered basic, established in a consensual manner and taken up by the Law (financial autonomy, participation of the different sectors and actors …) have not been developed, and have been put in words, as you have mentioned. It is true that in the last twenty years tremendous steps have been taken in the process of Euskaldunisation of schools (I do not know if by law, or by the work of schools and parents), but we still do not have the capacity to develop our own educational system. On the other hand, if we want to develop a regulated education of our own, in addition to political competences, we need our own reflection: What is the education system that we want and what peculiarities will it have?

Idigoras, as you said, the new law seeks to cover not only public schools, but also concerted schools. In this sense, ikastolas insist on the need to review the concept of advertising.

A. Ariznabarreta: The Basque Public School Law was innovative, but not because the administration was innovative, but because the Law endorsed the previous trajectory of educational agents in pedagogical innovations. Today, what is the administration going to do, bring together the different elements there is, reorganise funding in another way, or really want to organise the integrated system? That's the key question. The Administration says that the Law seeks a comprehensive and integrated educational system and that, in this sense, the concept of advertising is key. Our approach from ikastolas is to understand Basque education as a public service. Among all of us, we will have to specify what it means to be within this concept of advertising, what the foundations, principles and values of our educational system are, and all those who undertake to implement it will participate in the public service of Basque education. To the extent that they maintain a different ownership but fulfil the commitments, the networks shall participate in the financing and the rest, with all their obligations and rights. So we're going to define the education system as a whole.

A. Idigoras: For some 30 years these obligations have been met: not segregating pupils, how to hire teachers, and a thousand other issues; the problem is that the concerted network does not generally meet. So what credibility can those commitments have from now on? I think that is a mistake. Not only the ikastolas, the Christian schools and the rest of the private networks, among them the centers that separate students based on sex, question the concept of advertising, they want another concept of advertising. The Valencian PP no longer talks about the private concerted centres, but rather names them concerted public, arguing that they provide a public service. We can discuss whether cooperatives are more participatory and close to the country, but we are not prepared to discuss what is public and what is not. We are prepared to discuss, and must do so, what public educational model we want. But on advertising, what is the public domain, what is the public space?... We are in a complicated situation, and this historic journey that we have described a little bit between the three has brought us to the place where we are, with the consequences that the different educational models have had: The situation we live in the Basque Country and in the Basque Country is unparalleled in Europe. We have public education, the ikastolas, the Christian schools, ICE, other cooperatives… This, yes or no, has led to the hierarchy of society. Here is a phenomenon that does not occur anywhere else: “You’re the son of whom, how much money do you earn? Then you will learn at this school.” This reality is undeniable and public education in particular in the CAPV has great difficulties in moving forward, living the most subsidiary situation in history. We live in a state of apartheid: If an 11-year-old Algerian arrives in Vitoria-Gasteiz, he will be denied entry into most schools, although the taxes paid by his parents are used to finance these schools. This atomization has had very serious consequences on social cohesion, on peoples and on society, and I do not know if it is on the citizens' agenda to discuss what advertising is and what not. If we have to seek the harmonisation of networks, we can establish a new process of publication, and each one will decide whether it is public or private, but we do not believe that the extension of the public word as a gum so that we can all enter into the interior will bring any benefit to our educational system.

M. Bilbatua: One of the keys to answering this question about advertising is, in my opinion, also inclusive school. Our education system will be of quality if it guarantees that all people will have the same opportunities to receive quality education. Making it clear that this is the axis, the character of public will be given by the institutions to the centers, and to achieve that character the school or educational space that we can imagine must be open and open to the general public, and must guarantee the participation and control of the community. But I would not limit my public status to the centre that depends on the Basque Government; we have other references in other countries. Does the public school have to be the one that depends on the Basque Government, or the one that depends on the City Hall, on an institution that guarantees public control? Are municipal children's schools in Pamplona public even if they do not depend directly on the administration? Are consort children's schools public?... I think it is an issue that needs to be deepened, deepened in the school model that we want and asked whether the advertising model that we have is not closely linked to the working model that exists in Spain and France.

A. Ariznabarreta: I say the same thing, guaranteeing the right to education for all students without any discrimination is the basic principle of the education service, and from there all the other principles would be centred. The site that does not guarantee it cannot be recognized by the public service, and the same with the rest of the principles. For example, from the point of view of the citizen, we also see the need for social control, not just the control of the administration. It's a knot that we have to let go, and even if we don't get to do the law, discussing all these points is enriching to decide between everyone and everyone where our education system should go.

A. Idigoras: Yes, I agree to discuss the meaning of our education system. Mariam, in line with what you have mentioned, for us the ownership of the public school must be subject to the administration, the town hall or the government, but to the administration. It is true that ownership is not enough, but it is enough to clarify what is and what is not an essential public condition. We can discuss what public model we want, because it would be much more attractive and close to citizenship, for example, that of Finland, where municipalities have competences of almost 100%, but it is also an administrative education. Centres that have economic or religious interests have been inventing different concepts, for example Christian schools say they are social initiatives, ikastolas talk about social economy… but I think they have other priorities that are not social, unfortunately.

As you say, one of the main challenges when it comes to welcoming students is to achieve balance or equity between networks and educational centers to avoid ghettos. You talked about compromises, what steps should be taken to ensure that balance?

A. Idigoras: We always say: a neighborhood, a school. It's hard to understand why a network that puts equity as the first principle doesn't. I repeat, if I am an 11-year-old Algerian and under my house I only have a Christian school and ikastola, why am I not guaranteed a free and secular school in the neighborhood? Why do I have to go there? That's segregation, and the center that accepts segregation should not have a pact. When this Algerian comes to the public school, we will welcome him first and then ask him where he comes from, what he knows and what he does not. Today in the concerted centres it is being done the other way round: perhaps after the first consultation it is welcome.

M. Bilbatua: I think this is a debate that needs to be raised beyond school. A centre situated in a marginalised neighbourhood will hardly be able to obtain equity, whether public or private, if it is not supported by other services or if it does not receive special aid from the administration. Aitor, I understand your approach, it cannot be accepted that some schools do not receive the students, but I believe that if all the centres received them we would not solve the problem. So imagine the services we should have in these situations and we have examples in other countries, where social, educational and health services are concentrated in education 0-6 years in particular. The answer would lead to a broader scope: What kind of educational space do we need to respond to the needs of current cultural diversity and ensure the integration of all in Basque culture and full personal development?

A. Ariznabarreta: I agree with what you both said. And it is not possible to provide an equitable response to the needs of students without an equitable distribution of resources. It is not the same for everyone, but the same: according to socio-economic situation and needs, more for those who need it most. That is why we call for the same basic funding for all schools in the education system, and supplementary funding to address special situations, provided that the centres or groups of centres clearly justify their commitment to the continuous improvement of the principles mentioned above.

A. Idigoras: Those of us who work in public education face what's coming, regardless of the resources we have. That is, we have few resources, but that is why we will not close the doors to students with special needs. The public service, I insist, is that. Many educational centers with many resources come to mind, with quality Q and the like, with a lot of money… But more resources, less students with special needs. It's a class issue: elite centers have a lot of money and no special needs student; the resource argument is stupid.

A. Ariznabarreta: To make it clear, I will repeat: the ikastolas have repeatedly claimed that in each school area in which we are, we are willing to commit ourselves to the measure of our enrolment rate in the education of students with special needs. And we do; nobody who comes voluntarily has not been denied a registration, even when we have been assigned from the administration.

Not only in the reception of students, it is to assume that balance will have to be sought in other areas: hiring of teachers, management of the center, resources, financing… What criteria should the law establish to match the rules of the game?

M. Bilbatua: The 1993 Law states that schools can design and develop their own educational project, but in practice we see that there are factors that hinder the development of the projects themselves. The instability of teachers, for example, in relation to the hiring of teachers, is an important problem that the centers have today. I have seen schools that have very interesting educational projects, that have been weakening over time until they disappear, because they have not been able to guarantee the stability of teachers. The centre should have the competence to choose teachers, ensuring the autonomy of schools and the professional skills of teachers. They are able to guarantee both things in other countries. We should also be able to define the resources according to the peculiarities of each centre, because at present very homogeneous criteria are used and in one centre the ratio of 20 pupils may be normal, but in another centre it may be too high. We have to move to a model of autonomy based on the needs of each center. If we opt for homogenization in school organization and management, we will not achieve quality education. It is related to trust, because in quality educational systems the administration bases its relationship with the center on trust, while here prevails mistrust, as if the schools were claiming resources that they do not need or deserve.

On the other hand, the criteria based on academic results are very dangerous. Heziberri talks about something like this, and if it does so it can create serious problems, because when the aid and resources are organized according to the results and ranking, the schools allocate the teaching processes to the results, which is a serious detriment to education. There are ways to assess the results of the projects, but it is the project itself that should provide the indicators to know if it is developing correctly.

A. Ariznabarreta: Law 93 provides for pedagogical and curricular autonomy, and – within some frameworks and priorities – that each center can define the resources it needs in its educational project, as well as the economic management of these resources, personnel management. But this economic autonomy has not developed over all these years. That must be turned around, as Mariam said in the educational projects, and the rights of workers must be reconciled.

A. Idigoras: In Heziberri, the autonomy projects of the public centers are realized. It is curious that the law includes all public, concerted, private at the same time, but in this chapter dedicated to autonomy Heziberri only refers to public centers, as control mechanisms are put in place. It is mentioned to give an account to the cloisters and to pay special attention to the academic results, “especially to the academic results obtained in the individualized and final evaluations”. We have to address the issue of autonomy, effectively, but see what we mean by autonomy, because both in the LOMCE and in Heziberri autonomy is understood as a management model. That is, to transfer to the public the model that exists in the concerted centres and that, for example, the director or director has the power to dismiss a substitute. To the extent that we are representatives of trade unions and workers, we are opposed to this. And although they sell us that the Law is going to start from scratch, it is not so, because we already see in the decrees that Heziberri has brought out that the Law is highly conditioned, among other things, by the unification of networks or by the conception of autonomy.

And yes, teacher stability is necessary, but it is likely that any teacher – despite the pedagogical-methodological nuances – meets the criteria of public schools, although perhaps not with those of a Christian school. Because we have to differentiate the pedagogical project from the center and the identity of the center that is so vindicated. For example, 35 per cent of the educational network is in the hands of the Church, and the principles contained in these centers have to do with religion and the Gospel. That is why we see a need for the stability of teachers in public schools, but if we make a joint list of workers for the concerted and public centres, doubts will be raised about this, both for the worker and for the employers and for the cooperative world. If a homosexual and an atheist teacher touches the religious college, what?

In Catalonia, the system of hiring teachers in public schools is as follows: the director, not the school community, can decide if he wants a music teacher who knows the oboe, will look on the list which have that profile and it will be the director who chooses the teacher after an interview in the center. This is happening in public schools, in schools that have been integrated into autonomy projects. Under no circumstances can it be accepted, a middle way will have to be sought.

M. Bilbatua: I didn't know it, and I'm surprised that without any kind of guarantee and control, you can make these unjustified choices in the education project. When I say that school should have the right to choose teachers, of course, I put it in a concrete context.

They have put the autonomy of the centres on the table. All three of them are clear that academic results cannot be a gauge for autonomy. How to develop the autonomy of the centers?

A. Idigoras: Curricular autonomy is necessary, but that does, guaranteeing equal opportunities. Autonomy does not mean that we have to go towards a system standard, that everyone can do whatever they want, and that is what Heziberri proposes today: that everyone do what they want and we will accept it. Autonomy seems to be a topic, already approved for the Education Law without any kind of agreement, but it is a subject that needs to be deepened.

A. Ariznabarreta: It's okay with Aitor, but we don't think that autonomy is already given to us. Moreover, the administration has not yet completed the second phase of Heziberri, the decree is unpublished [as it was when we did the round table], and it is serious, because this course is in effect de facto and is not dismissed. What is the Basque Government waiting for the LOMCE to be suspended according to the new Madrid political landscape in order to withdraw the Basque Decree?

M. Bilbatua: Aitor, I was surprised that it was suggested that too much autonomy be given to educational centers for curriculum development. Because that is not real, we see that in the evaluations the students have to respond to concrete knowledge, and that the situation is inverse, you want a completely closed curriculum, conditioned by the evaluations of the LOMCE. On the other hand, in well-functioning countries, the administration designs very open curricula and leaves it to the centers to develop their own curriculum. Moreover, in Finland, for example, they are not conducting continuous evaluations during the learning process.

A. Idigoras: I don't know how it's been understood, but I just wanted to say that we have plurality and curricular flexibility, especially in Primary. For example, popular curricula are being developed in some places, indicating that there is a painting for it. Autonomy must mainly respond to the curricular sphere and not so much to the management of resources.

As you say, before making the law, Heziberri has already decided on several points in the first and second phases. One of them is the treatment of the language and advocates to maintain the three current models in schools (A, B, D), although the agents have long advocated the need to overcome them and develop an education focused on the Basque. What should be the treatment of the language in the new law?

A. Ariznabarreta: We have not taken too much account of the point that Heziberri has received, because no alternatives have been put forward at the moment. Both the School Council itself and different actors have long called for a different approach. The Law of Standardization of the Basque Country dates from 1982 and the following year these models were created, see in what context. The ikastolas have chosen to develop what we call the Eleanitz project, and that is where we have been since 1991. The Basque language is the axis, the first language, and along with it we have defined the level of knowledge of Spanish, English and French in the output profile: What is the linguistic competence the student should have at the end of compulsory schooling, as we do with other competencies? Well, taking into account the European reference frameworks, the objective is for the students to reach level B2 in Basque, in English B1, in Spanish B2 in the South and A2 in the North, and in French B2 in the North and A2 in the South. We act accordingly and as the ikastolas of Oion or Bermeo are not the same, each ikastola is organized according to the sociolinguistic context, always being clear what the output profile should be. Faced with the whole education system, the output profile should clearly define the competence to be achieved in the four languages, as well as the intermediate profiles for each stage, using the European framework. In this sense, the development of the linguistic projects of each center should have resources and a serious commitment on the part of the administration.

M. Bilbatua: You say that you are based on the output profile, but in practice you have chosen a model: the immersion or maintenance model [model D], and I believe that in the educational system we all have to go towards it. In the results we see: In model A the results related to the Basque country are very poor, and I would also add that the maintenance of model A goes against inclusion because in some cases the public centers that have this model become exclusion ghettos. The immersion model can be positive both for Basque learning and for inclusion, but as Abel says, being a unique model, I think it should be flexible, taking into account the socio-linguistic situation of schools and the diversity of students. The 2012 evaluations are there, and the whole system still has a lot to learn and do to achieve good results in the teaching of Euskera. In that sense, we are talking about multilingual Euskaldunes, but we have to be very aware of what it means to be Euskaldun.

A. Idigoras: Heziberri’s approach is the most brutal attack on the Basque Country in recent years. It makes an approach designed for the entire educational network, and from the reality of the ikastolas I share what Abel says, that within model D one can act flexibly taking into account the different situation of the concerted ikastolas of Oion and Bermeo, but that in Oion there is also a public center in a situation of subsidiarity, and if to that we apply the flexibility of the sociolinguistic context, I end [the course has a According to Heziberri, the achievement indicators of the Basque students will depend on the socio-linguistic environment of the center. The zoning of Navarre has, in some way, been transferred to the CAPV. Can the socio-linguistic environment never serve as a pretext for making achievement indicators more flexible, or does the law state that the results of mathematics in the Left Margin may be lower because of their worse socio-economic environment? The approach of the administration should be exactly the opposite: Does the center have worse socio-linguistic conditions? For in that college we will put forces so that at the level of Euskera we can guarantee indicators of achievement similar to the rest. What Heziberri receives is serious for the Basque: for example, it says that each center will choose the number of hours it will dedicate to English. In the case of the ikastolas, very well, but in the Christian school the administration has had to walk with the stimulus of introducing the Euskera, and when it has succeeded in getting many centres of model A and B to Euskaldunicen, it is now going back and the lack of standards mentioned above is imposed: that everyone do what they want. Moreover, Heziberri adds that in all centers, the first foreign language should be generalized as a communication language, until it becomes the vehicular language of the center.

A. Ariznabarreta: I totally agree. The socio-linguistic environment cannot be an excuse for making achievement indicators more flexible. What we say is that we put the achievement indicators and that the linguistic approach of the centre is the tool and the way to reach them. And with what we said about equity, that the center that needs the most resources also in the treatment of language receives more resources.

Needless to say, Euskaldunization is not the exclusive responsibility of schools, but of the whole of society, but it must be said that behind the evident progress that has been made in recent years in the process of Euskaldunization is the work that the school has done.

We are talking about Heziberri, and in part they are conditioned by the LOMCE its contents and orders. Will the Education Act for the CAPV also be subject to current or future Spanish law? Can we achieve our own model and our own law, or will it always depend on state law?

A. Ariznabarreta: At first I mentioned the influence of organic laws coming from Madrid. Educational competences are communities, but there is a trap there, because the State reserves two competences for it and, on their behalf, assumes all the other competences. One is the right to education and the other is qualifications. Who signs the qualifications obtained in education? The King of Spain. The organic law should be nothing more than a basic framework to guarantee the right to education for all students and the minimum necessary to obtain the degree. But the Spanish Government takes advantage of the title’s competence to go further: for example, the LOMCE has made the revalidated throughout the learning process. And in this way they manage not to lose control of the contents.

In this context, if through the debate between the agents we are able to agree between all and all what the north of education is from ten to fifteen years, if we are able to lay the foundations of the educational system and make commitments, in the long term this will have more value. And even if we collide with the organic laws of the state, it's worth it, if it's not to decide between everyone and all which educational model we want.

M. Bilbatua: I agree, if we had a joint vision between us, we would have more strength to deal with the aggressions that may come from Madrid and to look for different ways of dealing with these aggressions. I believe that unity against LOMCE is an example of this.

A. Idigoras: Abel has described it very well: while the titles are at stake, it is difficult to cope with the organic laws of the state. However, in the meantime, there are tools for a more just education or for deepening secularism. Looking to the future, the publication of all educational establishments and the handing over of all citizens of education would help to overcome the fragmentation and fragmentation of the system, to cope with the hierarchy of society.

The broadest agreement on education that has been reached in recent times is the Social Charter: we demand the right to education, the right of all people to a public education, Euskaldun, plural, secular and free, that integrates diversity and is egalitarian from a gender perspective; that promotes a critical vision and internationalist solidarity in all educational stages, both mandatory and non-compulsory. We have to go to that and everyone has to put it on their side, not from self-interest but towards a model that seeks the well-being of all. We have always claimed the need for a single Basque public school, because from there will be the fairest educational model of a possible free Basque Country.

M. Bilbatua: To what I say about individual rights, I would add the right that we as a people have to organize our education system. Around these two rights we should organize our model, combining the right of every person to receive a good education with the right to transmit our culture, our language, our history…

It also says that the road is the Basque public school. We have to build that public school with another model, we cannot be subjected to the models we have in Spain or in France. Nowadays, there are very interesting initiatives such as those of educational peoples, which allow us to imagine an educational space that goes beyond formal education. To meet the challenges of society, school is not enough and we need other services, we need to take formal and non-formal education into account in order to meet the educational objectives we have.

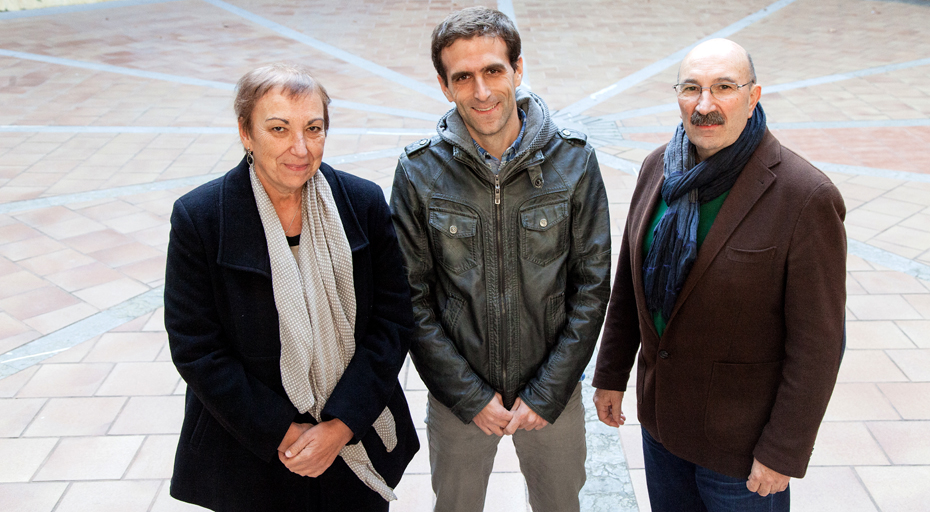

Mariam Bilbatua Perez, Mondragon Unibertsitateko irakasle ohia

Getxon jaioa (Bizkaia), 1950ean. Politika Zientzietan eta Filosofia eta Hezkuntza Zientzietan lizentziatua eta Filosofia eta Hezkuntza Zientzietan doktorea. Mondragon Unibertsitateko Humanitateak eta Hezkuntza Zientzietako Fakultateko irakaslea izan da Irakasletza graduan. Irakaste eta Ikaste prozesuak izan ditu aztergai. 2015eko urrian erretiroa hartuta, Mondragon Unibertsitateko zenbait ikerketa proiektutan elkarlanean jarraitzen du.

Aitor Idigoras Lasaga, Ikastetxe publikoko irakaslea eta Steilas sindikatuko kidea

Gasteizen jaioa, 1976an. Gorputz Hezkuntzako Irakasletzan diplomatua eta Jarduera Fisikoko aditua garapenean eta hazkuntzan (EHU), zenbait eskolatan kultur arteko dinamizatzailea izan da, baita “Etorri berriak eta aniztasuna Gorputz Hezkuntzan” proiektuaren koordinatzailea ere. Gaur egun Toki Eder ikastola publikoan irakaslea da eta Steilas Euskal Herriko Irakasle Langileen Sindikatuko kidea; zehazki, sindikatuko Hezkuntza Batzordeko koordinatzailea.

Abel Ariznabarreta Zubero, EHUko irakaslea eta Ikastolen Elkarteko hezkuntza arduraduna

Diman jaioa (Bizkaia), 1952an. Historia Moderno eta Garaikidean lizentziatua eta Psikodidaktikan aditu tituluduna. Irakasle eta aholkulari pedagogiko aritu da. Besteak beste, Gasteizko Irakasleen Eskolako zuzendariorde eta Eusko Jaurlaritzako Hezkuntza Berriztatzeko zuzendari, eta ondoren, Hezkuntzako sailburuorde izan da. Egun, EHUko Gizarte Zientzien Didaktika sailean irakasle eta Euskal Herriko Ikastolen Elkarteko hezkuntza arduraduna da.

Luis Dorao, San Martin, Lukas Rei, Barandiaran, Umandi… Arabako 27 ikastetxe hauetatik 19 publikoetan egin nahi ditu frogak Eusko Jaurlaritzak martxoaren 5etik aurrera Lehen Hezkuntzako 6. mailako ikasgeletan. DBHn ere Pisa azterketa egitera deituko dituzte 4. mailako... [+]

Ebaluaketak "merkatu eta politika neoliberalen menpe" daudela kritikatu du sindikatuak eta proba "jarraitu eta hezigarrien" aldeko dokumentua aurkeztu du.

"Legegintzaldi honetan EAErako Hezkuntza Legerik onartzen ez bada, porrot itzela izango da, guzti-guztiontzat". Hala mintzatu da Koldo Tellitu Ikastolen Elkarteko lehendakaria, ikastolen hasiera ekitaldian.

Kanpo-azterketa berriak, aldaketak ikasgaietan, ingelesezko ordu gehiago, ebaluaketa irakasleei, mugimenduak goi-karguetan… Bero dator ikasturtea Hego Euskal Herrian, LOMCE, Heziberri, Ingelesez Ikasteko Programa edota D ereduaren zabalkuntza tarteko.

Maiatzaren 27an bukatzen da Lehen Hezkuntzako 3. mailako azterketa polemikoaren emaitzak Eusko Jaurlaritzari jakinarazteko epea. Hezkuntza Plataformen Topaguneak jakinarazi duenez, 175 ikastetxetan planto egin diote probari eta elkarretaratzeak egiteko baliatuko dute azken... [+]