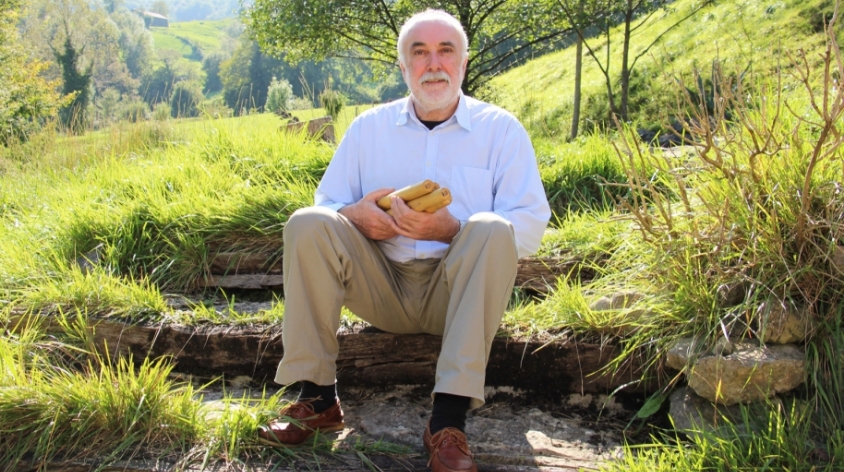

"I don't like selling Bertsolarism as a model for other cultural activities"

- It has not yet come down from foams, it is too early to take a closer look at what it has been like to be the new Gipuzkoa champion. Knowing that, we have tried to speak as little as possible of the end and as much as possible of Bertsolarism. Issues such as the new generation, collectivity or inertia of bertsolaris have emerged.

“With Ajo they answered the questions about the final. Let it at least respond with a clear head when it comes to the chess of the final.” The voice of Inés spoke to me, as usual, from that thin line between the council and the sermon. “Thinking about it better, ask about everything but the end. Take it to a place where you feel comfortable, in that mountainous area of Añorga there are many. Why don't you try it, for example, with the Lukainkategi Steakhouse? It's less than 50 meters from her home and you know what, the other day I found Jakoba Errekondo. Surely if you leave it will be a good place. Do you know where Lukainategi's name comes from? It's a pretty story. It is said that a Good Friday hunted Praxku in fraganti eating a piece of sausage and then ...”. Few things are more annoying than the continuous murmur of the ear. I ordered Inés to shut up, but Inés wasn't close. Instead, I met Beñat Gaztelumendi and a burning recorder waiting for me to ask the first question.

They say that in this championship you have found your place to sing the world. Voice of its own. How does a bertsolari get it?

The verse has two characteristics: the technique, composed of size and rhyme, and the content that you include in it. Even though they are united, they are two different tasks. We all learn the same technique in the bertso-eskola: making lists of rhyme, working melodies ... There will always be more technical bertsolaris, but all of us in the championship have the least technique to say what we mean. The problem is what you use this technique for. It's a silly attempt to say what you mean, knowing you'll never get it, because technically you won't get there, because the words you choose won't tell you exactly what you had in your head, because words have their own ideological weight. In the championship, I've tried to sing right now from my position of seeing the world, as close as possible to what I wanted to say. I've tried to look for edges to the themes, to put them into the skin of the characters, to make the most realistic bertsos possible, without adornments. The bertso is to continuously fight with yourself, and you usually lose it.

There is therefore a preliminary reflection on what you mean. Has bertsolari passed from singing in a more intuitive way to singing in a more premeditated way?

More than what I mean is where I mean it. Be as clear as possible where we are in the world, where we are talking about. When I start singing, I don’t think “I want to launch this message.” Bertsolaris usually don't, and if they did, it wouldn't be good. It is true that Bertsolarism is changing: the first finishes were loaded more, there was a tendency to sing more absolute reasons. Now, instead of wasting a fat speech, you tend to look for the ends of that speech, leaving aside majestic reasons. The inertia is still there, of course, and they're even stronger in the competition: having so many friends in front of you unwittingly leads you to take a lot of reasons, to fit as many people as possible. But what I really do is look for the edges of those big reasons. This is what I rarely get and what I really would like to do.

Can you generalize, more or less, the characteristics that you mentioned to your generation?

I don't know how the new generation sings. Agin Laburu one way, Alaia Martin another way... In the criticisms it was mentioned that Alaia and I approach the jailer in a similar way, and it may be, but in the plaza we notice the differences. More interesting than talking about generations is that everyone makes their contribution, looking inwards and discovering a different place to see Bertsolarism.

From the point of view of bertsolari yes, surely, but from the point of view of the critic it is very interesting to observe the general trends. Based on isolated cases it is difficult to create critical elements.

Yes, and this Gipuzkoa Championship has given more comprehensive readings: for example, the Basque conflict has hardly been sung, prisoners have hardly been mentioned. The issue has changed, on the one hand, because the issues that have been raised have rarely touched on that and, on the other, in open issues, such as those of prison, when it has touched on bertsolari choose, it has not touched on that. On the contrary, there has been a lot of singing about relationships as partners, about relationships within the family, between friends ... It's not just Bertsolaris, society has changed.

The way to understand the intergenerational relationship – the transition from the old to the young, the insistence on movement – and the cultural theorization – the idea of transmission, etc. – that entails – the idea of transmission – is very widespread and shared in Bertsolarism. It is often used as a model of Basque culture. Do you think it is exportable to other cultural disciplines?

Each discipline has its code. The code of bertsolarism is very appropriate for that transmission, because we share the creative process: we are on the same stage people of very different generation and conception of the world, and we are forced to build actions among all. On the other hand, Bertsolarism cannot be done in another language, it must necessarily be in Basque, and that also makes it very easy. I don't think that example of Bertsolarism comes from us, at least I haven't experienced it that way. Moreover, I do not like Bertsolarism when it is sold as an exportable cultural model, because it does not seem to me that it should be. Each discipline should function in its own way, according to its codes, according to its needs. I think we should build more interdisciplinary bridges, and that's why it's not good to put anybody as a model.

In the post-final talks you have very much underlined the collective value of Bertsolarism, always with a positive connotation. Do you think of the risk that this community can have?

Being a collective has the risk of falling politically into the right thing, or of moving above the intentions that it can have as a creator. In any case, collectivity and identity are always united. The bertso is not just collective. I, for example, live the bertso in a very intimate way, closely linked to my experiences. But it's also not right to understand Bertsolarism as a personal thing, it stays limp without movement. When 7,000 people get excited in the dark, not only are they excited because the verse they've heard has reached them inland, but because probably in four years they haven't had the opportunity to meet at such a core, in an event entirely in Basque. The two cannot be distinguished. Bertsolarism cannot be understood without bertsolarism.

You said that a verse, to be good, among other things, has to reach the listener. However, there are many ways to reach the listener, and one of them can be making him uncomfortable, trying to question his values and beliefs. I have the impression that this path is not taken so often.

It is sometimes difficult to deal with internal inertia. A good bertso has that decision inside: If bertsolari has been able to choose whether the audience wants to sing something that they're comfortably listening to, or whether it's uncomfortable. This decision becomes apparent when it is taken by inertia. I can think of a few examples of uncomfortable moments, though: In 1997, at the Velódromo de Donostia-San Sebastián, Jon Maia and Unai Iturriaga were given a subject that said about: “You are two girls, so far very friendly. Now you have realized that you are more than just friends.” When the subject was heard, the public laughed. Jon Maia ended the first verse by saying, “I don’t understand why you all laugh.” There's a path to bertsolarism: trying to tickle, trying to question some built ideas. We must strive for this, always bearing in mind that we must start singing within ten seconds of having heard the subject. But there are more cases. I do not think, for example, that Maialen Lujanbio could sing comfortable things at BEC, on most issues.

Surely in recent years the most uncomfortable voices have come from feminism. They have dared to put upside down the values of a community, making them feel very uncomfortable.

Yes. There's a lot to rethink: for example, when men sing about mistreatment, we always do it from women's skin. We always sing from man, and doing it from woman when we are just victims, uniting myself “woman” and “victim”, seems dangerous to me. In a jail, it would be interesting for a man to sing from the role of a batterer. How have you suddenly gone on to do something like this? How did you build that power relationship? Of course, you have to be very good at explaining that in three bertsos – Unai Iturriaga did in BEC in 2009. There is a wide spectrum to sing. But to make your way, you have to be very sure of yourself. If you have questions about whether you will be able to do it in three verses, it's hard to play around. It would be a valuable effort, but easier to do at a festival. At festivals you see the faces, you know how far you can go in that stretch. The initial sensation of the championship is usually fear, not trying to fall, so it is difficult to seek discomfort. But I want to try. I would like to seek that assurance.

In recent years, I have made little progress. I have said it many times, I know, but just in case. Today I attended a bertsos session. “I wish you a lot.” Yes, that is why I have warned that I leave little, I assume that you are attending many cultural events, and that you... [+]