Today's business, tomorrow's shortage

- Since agriculture was created in the Middle East, farmers, in addition to planting seeds, have kept them and changed. This control has enabled species heterogeneity and food sovereignty to be maintained. But in the 20th century, industrial agriculture has called into question the millenary process. The seeds have remained in the hands of a few companies that have put their economic objectives above all else. There are few seeds in the hands of a few.

The process of modernization of agriculture of the 20th century, the Green Revolution, brought with it a series of changes: agricultural production to industrial measure, new technologies, genetic research… It has economic and technical roots, and although it has its origin in the 18th century – the company of first seeds, French Vilmorin, was founded in 1743 – the true rupture occurred in the middle of the 20th century. The transport industry in the Second World War switched to tractors and machinery, and that of chemical weapons to fertilisers and herbicides. Until the 20th century, seed companies were small, family-run businesses. In the 1980s, transnational corporations emerged that control global agriculture.

These transnational corporations come from the chemical industry and have acquired small seed companies, increasing the production and sale of chemical fertilizers in recent years. Thus they control the whole “technological package”: seeds, technology, machinery and chemicals.

Large companies have two annual channels to ensure the sale of their seeds: registers and patents in Europe and GMOs in countries of the Global South. Marc Badal, a member of the Seed Network of Navarra, made it clear that: “Seed is at the same time product and medium of production, and that’s a problem for industry.”

In the case of GMOs, it is easy to secure the sale because they are products of genetic engineering and are therefore patent. Farmers cannot therefore store the seeds for replanting next year. In Europe, on the contrary, GMOs have historically been poorly seen and there are numerous regulations prohibiting their marketing – at the moment, Monsanto’s MON810 maize is the only one that can be produced commercially. Thus, the forms of annual seed purchase by farmers are common seed patents and registers.

Patent legislation and seed registration

After the failure of attempts to implement European legislation, seed legislation is now in the hands of the states. To be able to market a seed it is necessary to be registered. However, to remain in the register, the variety of seeds must be stable, homogeneous and different from other seeds. Because of these characteristics, the records do not support local variants. Yes, yes, the homogeneous seeds of agro-industry. Professional farmers with industrial production must use registered seeds to market their products.

Local varieties are therefore limited to small productions, but also “small” farmers often prefer registered seeds for two reasons. Registered varieties, as in the case of origin marks, are easier to market, and farmers often do not know local varieties. And by not using them, they're losing out.

María Carrascosa, a member of the Seed Network of Andalusia, criticized that registers promote homogeneity and that there is no policy to defend the exchange and sale of seeds: “In the Spanish State there is a 30/6 law on seeds and nursery plants that can help farmers to exchange and plant their seeds, but this law has not yet been developed and the current regulations do not encourage local varieties.”

Carrascosa is clear that behind this policy is the pressure capacity of the agro-industry: “Farmers’ sovereignty is not profitable for large companies in the sector. They need subordinate agricultural models and governments, through their public policies, promote models far from food sovereignty”.

Increase in GMOs in the global South

If the transition of the agricultural model in Europe has been secular, a "quick and brutal" change is taking place in Hegoalde, according to Marc Badal, especially in South America. In the areas where varieties of fruit and vegetables were abundant, today we can find gigantic production of soya and maize. Paraguay is the clearest model: 80% of agricultural land cultivates GM soya and is the fourth largest producer in the world.

Agro-industry “obliges” local farmers to plant soya in order to produce animal feed. The same applies to maize, palm trees and similar monocultures. “It claims that agro-industry aims to feed the world, but the real goal is to produce raw materials to meet the demand of the West,” Badal said.

The economic situation also makes farmers bet on GMOs. According to Badal, the industrial and GM models allow farmers to reduce costs. It sets an example: “Instead of hiring people to get rid of weeds, you can plant a herbicide-resistant GM and with just one tractor you can throw a chemical toner for a couple of hours.”

Some GM adaptations are genetic adaptations to achieve “economic viability”: the joint maturation of all plants, the possibility of planting them with higher density on their own, the generation of a superior product other than the fruit or the resistance of the plant to the chemical fertilizers produced by the company itself to sell the whole “technological package” to farmers.

Food security at risk

Both the promotion of GMOs in the South and the establishment of the seed register in Europe have the same effect: having fewer seed varieties. According to FAO, 75 per cent of local varieties have been lost in the twentieth century.

This can have very serious consequences in case of drought, temperature changes, pests or other unforeseeable incidents. All plants would respond in the same way, and if the bad crops were chained one after the other, there would be a risk of cutting almost all global production. Badal believes that there is biodiversity in the world, but the process of loss is very rapid due to the spread of GMOs.

Faced with this, many Governments and institutions have launched projects to maintain heterogeneity. The best known is the seed store of Svalbard (Norway). In the giant warehouse that has been built in the Arctic, there are seeds of about 840,000 species, 500 of which correspond to each. Badal considers that these are “interesting” projects to maintain heterogeneity, but to create heterogeneity one has to “use” the seeds. Badal distinguishes two types of conservation, ex situ (laboratories and warehouses) and in situ (agriculture). “The seeds must be kept on their own, as only then will they improve and adapt.” This work is carried out today by the citizens of the seed network.

Seed networks began to work in the 1990s. The Basque Country was founded in 1996 and currently has about 200 members. Joseba Ibargurengoitia explained that they work in many areas: “Obtain knowledge about these variants, acquire biological material, carry out prospections and research, classify and preserve material”.

They also disseminate and disseminate: workshops and talks with unions, farmers, municipalities… “Listeners are surprised when we tell them the problem and when they realize the gravity of the situation they help us a lot.” He says that in recent years they have had a great boost and that the number of partners has increased.

However, it is not an easy task to collect and store seeds from the local variety, as the process is different. When the vegetable or fruit comes, you do not have to pick up part of the harvest, because you have to give the seed time before you pick it up. This entails an enormous economic and time cost for a professional farmer, as that part of the harvest is lost. In addition, large quantities of the species must be planted to ensure pollination.

For this reason, María Carrasco finds it difficult for farmers to rely on local varieties: “Professional producers cannot be so at risk.” The key is to raise consumer awareness. “We have to be prepared to pay more for the products, because if not the farmer, whether organic or not, will not support local varieties,” Badal added. Ibargurengoitia believes that it is still possible to turn the situation around, as long as seed network projects progress. As has been done with organic farming, the next step is to make known the importance of local varieties.

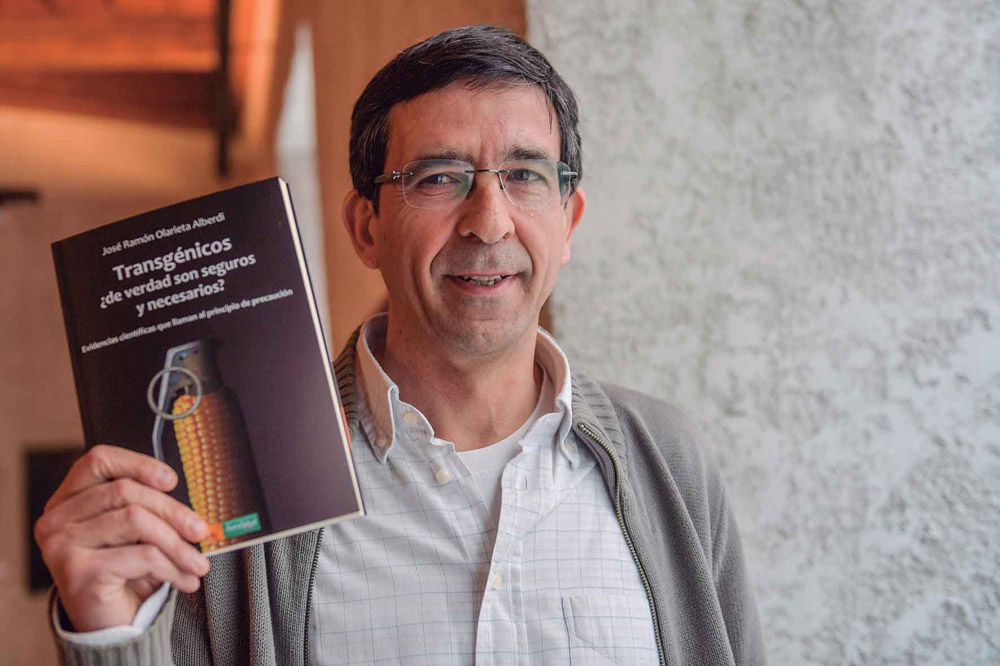

José Ramón Olarieta Alberdi is a doctor in agronomist engineering and professor at the University of Lleida, as well as a member of the Catalan association Som what Sembrem.El last year published a book on transgenics: Are GMOs really safe and necessary? In April, Leitza and... [+]

Soja laborantzara bideratutako nekazaritza estentsibo landa batean egin zuen lan Tomasik. Landa gunea fumigatzeko erabiltzen ziren agrotoxikoek eragindako gaixotasunaren ondorioz hil da.

Sinadura bilketari eta herritarren protestei entzungor eginez, Europar Batasunak baimena eman dio Bayerri Monsanto erosteko. Horrela, hazi eta ongarri kimikoen munduko enpresa handiena bilakatuko da.

Laborantza-industrian egin den inoizko akordiorik handiena gelditzeko eskatu diote milioi bat lagunek Europari: Monsanto eta Bayer enpresek indarrak batuko dituzte galarazi ezean. Hazi transgenikoen eta industria farmazeutikoaren arteko lotura 2016tik datorren arren, azken... [+]

Europako Batzordeak iragarri du sakon aztertu nahi duela Bayer konpainiak Monsanto erosteak kalterik egingo ote dion pestiziden eta hazien merkatuari. Bruselak adierazi du fusio-operazioa burutzeak bi arlo horietako munduko enpresarik handiena sortuko lukeela, eta horrek... [+]

Egun erabiltzen diren hazi hibridoak multinazional espezializatuek soilik egin ditzakete, eta horien liderra Monsanto da. Merkatura zabaltzen dituena, berriz, Heinz multinazional boteretsua da. Bide beretik jarraituz gero, elikadura merkatu pribatuen eskuetan bukatuko duela... [+]