Wide seas

Beñat Sarasola uses the word in the preface: force. Jorge de Sena (Lisboa 1919–Santa Barbara, EE.UU. 1978) is an example of an unconformable form of poetry that had poetry as a trench of that spirit. He left two fundamental novels in Portuguese literature (Sinais de fogo y O física prodigioso) and several criticisms and studies. But he was a teacher of lyrical, always in search of a word. “My land is not inexpressible./ The inexpressible thing in my land is life./ The inexpressible is what cannot be said.”

Rikardo Arrangi has approached us through this translation to the work of the poet who, without taking into account the limits of language, always sought new meanings. From Portugal, through Brazil, to the United States, the path of Sen has been from hermetism to surrealism and from there to direct and effective poetry. Therefore, he did not join the neorealists, nor slipped clearly into thought, and whoever wanted to leave “all said anyway” inevitably collided with infinite forms: “Talk to me about the mysteries of poetry, the traditions of a language, of a race, of a people or of a language, of what is only said. Donkeys.”

The poet made a bitter critique of the writer, of the faculty, in turn, of the world today. Wise, cultured and full of complacency, perhaps that habit of speaking categorically turns it into its lyric so beautiful, so aggressive and concrete: “In Crete, with the Minotaur,/ without poem and without life,/ without homeland and and without spirit,/ without anything, without anyone,/ with the only exception of the dirty finger,/ I will drink my coffee at peace.”

Reading this notebook, it occurred to me that I had to be submerged much more than the Sussians have discovered, in many other ways. From Rimbaud to Quevedo, from the ellipse to the raw word, the seas that Jorge de Sena travelled – in his youth Cape Verde, Angola, Sao Tome at the Sagres Naval School – seemed to be infinite, as their lives.

It was a total poet and no treason. Also in these translations some pieces may be more rounded than others, but all have a certain northern demand regarding what is written. That demand is that it be at least an honest poem, that it be at least aesthetic, ideological, historical, written from freedom.

Jorge de Sena

Itzulpena: Rikardo Arregi

Susa, 2015

Andrea Velasko dietista eta nutrizionistak elikaduraren bidez menopausiak eragindako aldaketak kudeatzeko zenbait gako eman ditu.

BRN + Auzoko eta Sain mendi + Odei + Monsieur le crepe eta Muxker

Zer: Uzta jaia.

Noiz: maiatzaren 2an.

Non: Bilborock aretoan.

---------------------------------------------------------

Ereindako haziek ura, argia eta denbora behar dute ernaltzeko. Naturak berezko ditu... [+]

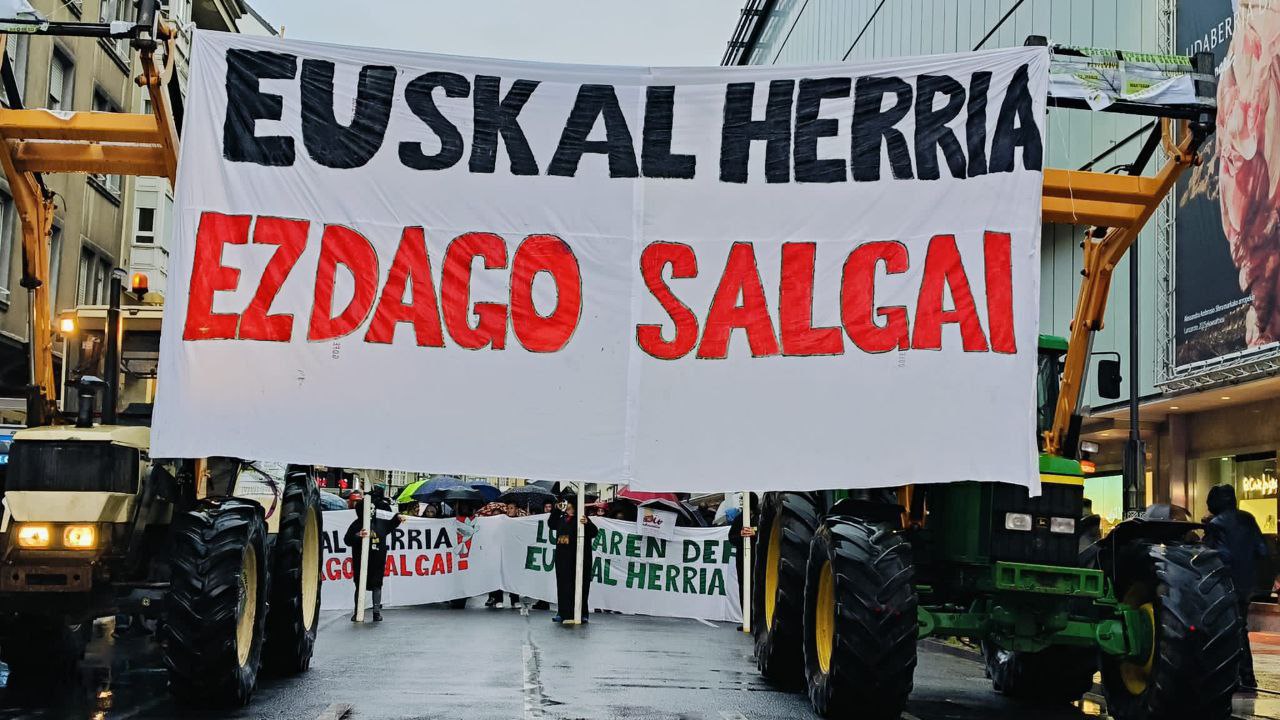

Antonio Turiel fisikari eta CSICeko ikerlariak aspaldiko urteetan ez bezala bete zuen Hernaniko Florida auzoko San Jose Langilearen eliza asteazkenean. Zientoka lagun elkartu ziren Urumeako Mendiak Bizirik taldeak antolatuta Trantsizio energetikoaren mugak izeneko bere hitzaldia... [+]