"Laws on dignified death require too much suffering before sedation is put in place."

- San Sebastián, 1944. As a young man, he studied engineering. After dedicating most of his life to the professions related to this field, after retiring he dedicated himself to studying anthropology at the UPV. At the end of the day, he chose death as a theme for his doctoral thesis, “because it is a field that is poorly worked and there is a democratic vacuum; people cannot always die as they want.” Olaizola has said that, in any case, more and more people are empowered to organize the end of their lives.

In recent years Iñaki Olaizola has been investigating in depth our relationship with death. As a result, there are two books, the last one published this year, Death, funeral ritual and mourning in Euskal Herria (Death, the funeral ritual and mourning in Euskal Herria).

You say there are two contrasting life models of death: the traditional one, largely linked to religion, and the biographical one.

They are extreme and there are many possibilities between them. It's in this interval where most people are located.

Have you invented the adjective “biographical” yourself?

I think so. In short, death is related to life itself. And when I say death, I mean a time, a concrete moment not to die. At one point you realize that you're in the last stage of life, and the mindsets change. Today we tend to die of old age. And normally, after a long period of illness or dependency. We live an average of 6-7 years in dependency. It is an important social problem that institutions and laws should take into account.

From the conversations you have made in the book it follows that more than death itself, we are afraid of the previous process.

Most people fear dying badly than dying. What is quality death? Well, there are the two models. The idea of the Church is still in force: a quality death needs suffering. Drafting. I think almost nobody believes in that today. Many people, and especially women, who know well what it is to be caregivers, don't want to be dependent. Hence come some reflections on the meaning of life. Do all lives make sense, as was said before? Well, no. It is an emergent phenomenon: there is no longer a single discourse, there are many possibilities of relating to death. As biographies are varied, so are deaths. There's a bit of rebellion against the system.

Choosing to end one's own life is always a difficult topic to discuss...

Now there is an important debate about dignified death. A law is being drafted in the Basque Parliament, which already exists in the territory of Navarre. But to do what they did in Navarra, better not to do anything.

Why?

Because it only takes physical suffering into account. But how do you measure that suffering? They don't take into account psychological suffering, internal sadness... The CAV is working on a bill, and they called me to give me my opinion. I don't like the law they're doing. They say they want to improve the quality of death, but they put such harsh conditions... They talk about the deadliest state, the irreversible state... In other words, it is necessary to wait too long for sedation to be achieved. It becomes fashionable to talk about voluntary death again. Now laws are being made about this, but who has the right to make a life that you do not want to live?

Frankly speaking, are we talking about suicide? It's a harsh word yet.

There's a misuse of language. If you mention euthanasia -- always taking into account that you're in a very bad state, which is not a whim -- you mean helping a person die. He would take some medicines and die within a few minutes, in a quiet place, next to him, in the company of the people he wanted. On the contrary, sedation consists of saying in the same state that “we can’t help this person die but take away the pain”, although with the medications given to him it is known that he will die a few hours later. The discourse is different. Whoever gives the sedation says that the goal is to remove the pain, even if he knows that he will die, and euthanasia is to know that the only solution is to die, to say the same word: let us help him die.

The same goes for words.

Yes. But speech is very important, because behind it there is an intention. One example: after this interview, I have to go to a funeral. My sister-in-law died two days ago. He was sedated at 11:15 in the morning, after suffering unfairly. After sedation, the woman still lasted 22 hours. 22 hours in very critical condition, breathing... The doctors said “no, no pain.” There is no right. I said to the doctors: “Can’t you put more doses?” “No, that would be euthanasia, we’ve taken away the pain and enough.” Discourse, therefore, influences. You know he's going to die, but all you have to do is take away the pain. And there are ten hours, or twenty, or two days involved... And then, it is true that whoever dies is the subject of his death, but also the neighbors must be taken into account.

We have talked about the influence of religion, but also about the paternalism of medicine.

Yes, I do not like the CAV bill to which I referred for three reasons. One: excessive suffering is required; the solution will come, but after unnecessary suffering. Two: the fake speech that you use is forbidden to help you die, and what you have to do is remove the pain, even if you know where it takes you. That's a lie, let's notice things by their name. And three: Where does that power come from to doctors? Why should their will be above the will of the person in this situation? Where have you learned for that? Whether or not there is a right to death, it is not a scientific issue; the person who has reflected on the subject has to be able to decide, there is no need for a degree for it. And well, there are psychologists, sociologists, cures -- whoever they want -- or friends. Why do doctors have to decide, where does that ability come from?

In the book you say that until the 1960s in Euskal Herria there has been no more than a traditional model.

That's right. It was then that the other model began to emerge. There were cultural and social changes. For example, as we said before, we now die of old age, and many times after suffering from a chronic disease. There was none of that before. Most of the time, the patient went right away.

Those social changes. Culture, for its part, has been two, above all. One is the identity that the person has acquired, the empowerment. “I command in my life.” The other is that the influence of religion has weakened, the relationship with it is not like what our ancestors had. Religion has made death its specialty. And the Church does not do its job well in terms of the rite of death.

Why do you say that?

Because they do funerals of very poor quality. There may be two burials on the same day, and a priest who knows nothing throws the rally. Your speech is not credible to most. You should keep in mind that he's civil, or at least half is not a believer, or the dead or his loved one, and they go for social action there. But the Church doesn't work on that. They speak only to believers of the resurrection of the flesh, etc. On the other hand, they could not do it well intentionally. Almost one in a hundred people die every year. In Hernani, let's say, there are 200 funerals a year, and today there's only one priest. How do you prepare it? How to prepare a speech adapted to each dead person?

So why do you propose building civilian cathedrals?

Yes. Anthropology distinguishes between places and not places. The place, in anthropology, is a space where you create sweetness, nice feelings, an easy conversation -- a space that confirms you as a member of the group. And as an example of non-places, airports are often cited. For a believer, the church is an anthropological place. But you have to find places for everyone. For some it will be the City Hall, for others the mountain, the sea... That is why I say that, on the one hand, we should make civilian cathedrals; anthropological places for the final farewell. On the other hand, we must not forget that the churches have been built at the expense of the people’s money, and that for many people, even if you do not believe it, they are anthropological places: the last goodbye in the church of the people is the calendar. Therefore, each church should have two managers, one religious and the other civil, to perform acts of both kinds. And in neighborhoods and villages where there are many churches, some could be used for civil acts and others for religious acts.

He says that the spread of the biographical model with respect to death is an emerging phenomenon. However, if the deceased has not previously expressed his will, it is automatically introduced into the wheel of the traditional system.

Among other things, we must not forget that the funeral services sector is very strong. More than 20,000 funerals are held annually in the CAV. That makes a lot of money. And that sector drives a certain way of doing things. This upward trend is therefore sometimes limited.

Gizonak ustez Ortuellako Jendea futbol taldean zuen posizioa baliatu zuen umeari argazkiak egiteko. Ertzaintzak ikerketa abiatu du eta aurretik antzerako salaketak zituela jaso dute.

Agintari gutxik aitortzen dute publikoki, disimulurik eta konplexurik gabe, multinazional kutsatzaileen alde daudela. Nahiago izaten dute enpresa horien aurpegi berdea babestu, “planetaren alde” lan egiten ari direla harro azpimarratu, eta kutsadura eta marroiz... [+]

Abdullah Öcalan buruzagiak PKKri otsailaren 27an eskatu zion armak uzteko. Taldeak egin duen adierazpenean babes osoa agertu dio buruzagiari eta Öcalanek eskatutakoa betetzeko konpromisoa adierazi du.

Poliziaren eta manifestarien arteko talkek atxilotu eta zauritu ugari utzi dituzte ostiralean herrialdeko hiri nagusietan. Herritarrek gertatukoaren erantzuleak zigortzea eskatu diote gobernuari, ez baita oraindik istripuaren inguruko epaiketarik ireki. Greba orokorra deitu... [+]

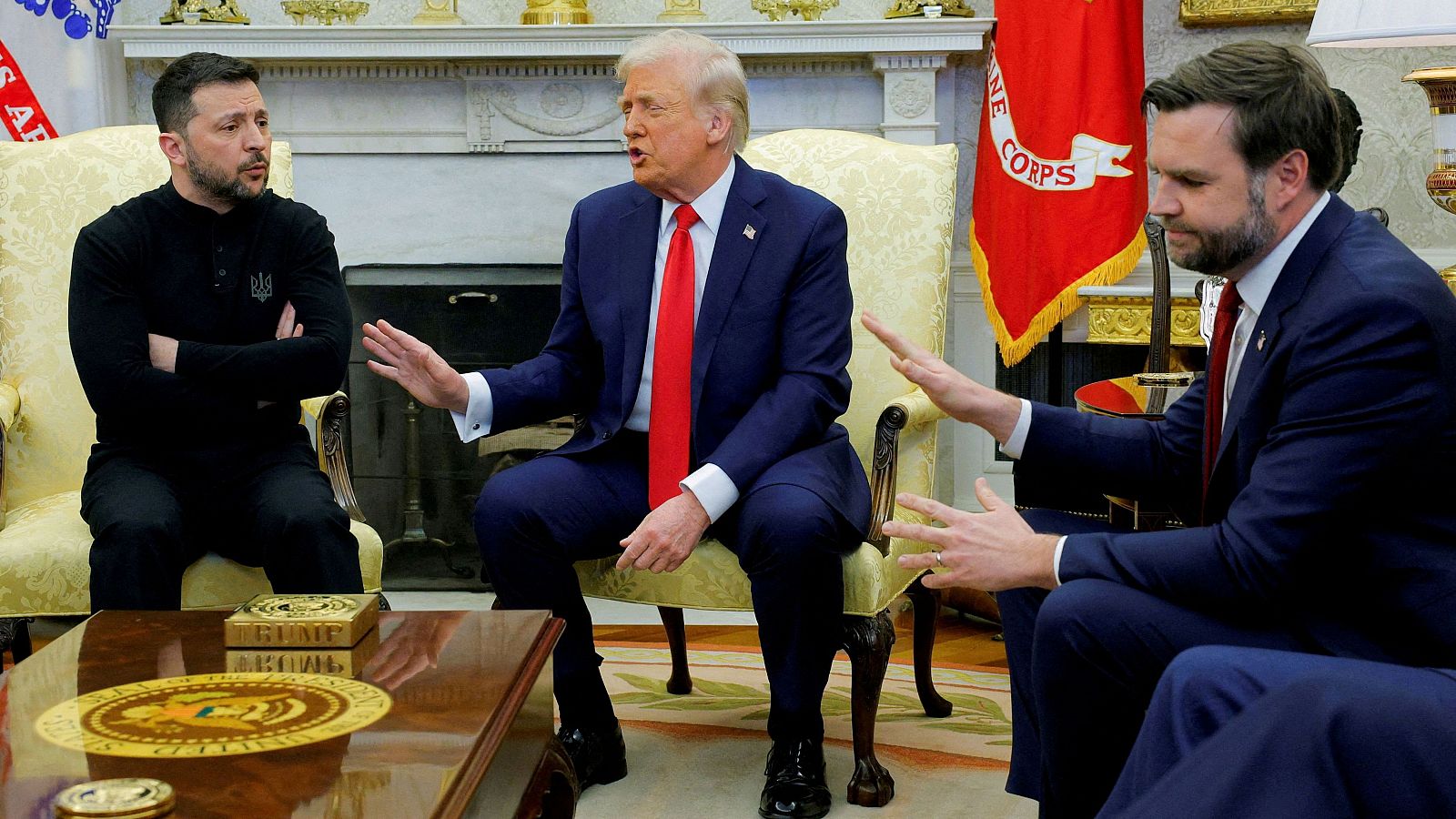

Hala iragarri du Keir Starmer Erresuma Batuko lehen ministroak Londresen eginiko goi bileran. Etxe Zurian Trumpek Zelenskiren aurka egin ostean, izandako eztabaidaren aurrean, Europako buruzagiek babesa adierazi diote Ukrainako presidenteari.

Elizak 23 kasu ditu onarturik Nafarroa Garaian. Haiek "ekonomikoki, psikologikoki eta espiritualki laguntzeko" konpromisoa adierazi du Iruñeko artzapezpikuak.

Karbankulu pomelatua "garai batean gure bizilagun Francisco Casanova hil zutenen ideiak babesten dituztenek erabilitako ikurra" dela, adierazi du Noelia Guerra UPNko Castejoneko alkateak, eta sinbolo "ez ofizialak" udalaren espazioetan erabiltzea... [+]

Mendizale batek asteburuan ikusi du animalia Lapurdiko Azkaine herrian, eta otsoa dela baieztatu du Pirinio Atlantikoetako Prefeturak. ELB lurraldean "harraparien presentziaren kontra" agertu da.

Elkarretaratzea egin zuen Aiaraldeko Mendiak Bizirik plataformak atzo Laudioko Lamuza plazan, Mugagabe Trail Lasterketaren testuinguruan.

EH Bilduk sustatuta, Hondarribiako udalak euskara sustatzeko diru-laguntzetan aldaketak egin eta laguntza-lerro berri bat sortu du. Horri esker, erabat doakoak izango dira euskalduntze ikastaroak, besteak beste.

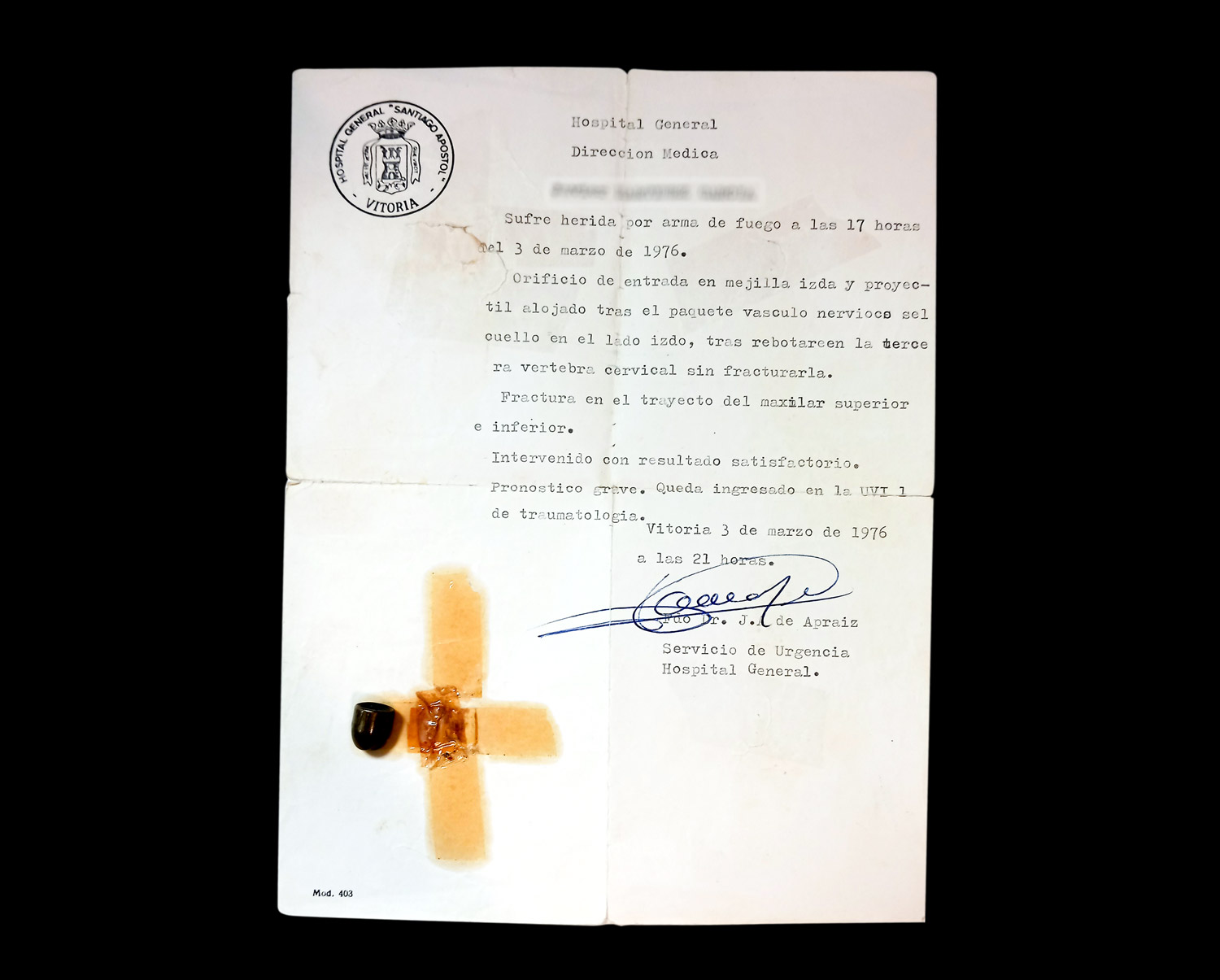

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Martxoak 3ko sarraskiaren 49. urteurrena beteko da astelehenean. Grebetan eta asanblada irekietan oinarritutako hilabetetako borroka gero eta eraginkorragoa zenez, odoletan itotzea erabaki zuten garaiko botereek, Trantsizioaren hastapenetan. Martxoak 3 elkartea orduan... [+]

Udaberri aurreratua ate joka dabilkigu batean eta bestean, tximeletak eta loreak indarrean dabiltza. Ez dakit onerako edo txarrerako, gure etxean otsailean tximeleta artaldean ikustea baino otsoa ikustea hobea zela esaten baitzen.

.jpg)