Life styles

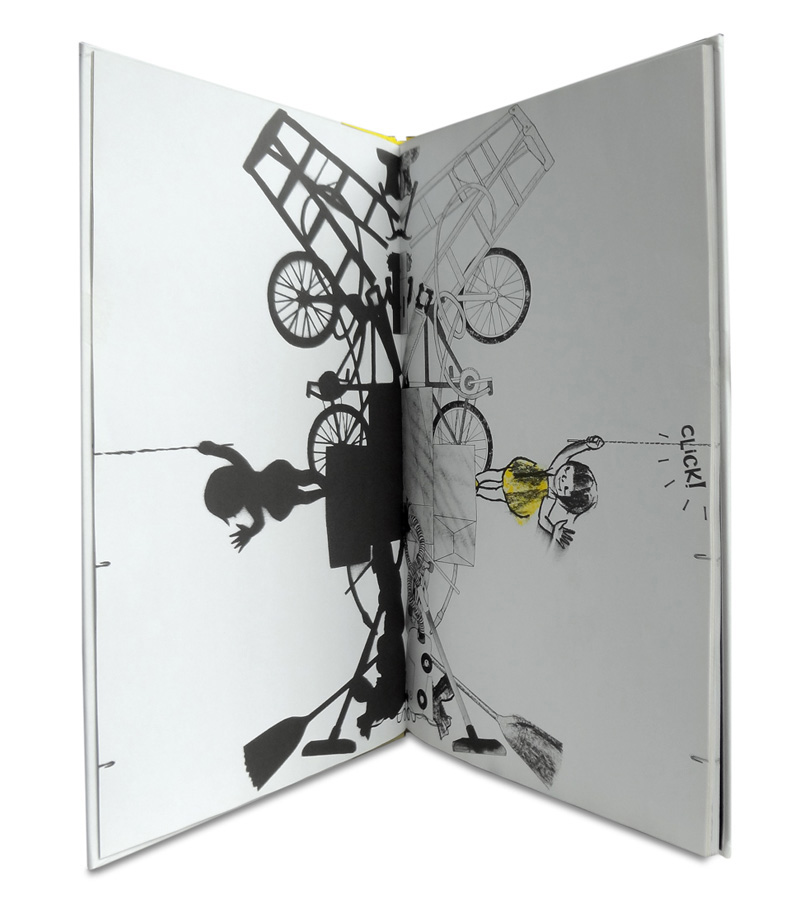

- With the excuse of a retrospective, we were able to get to know Sophie Calle better (Paris, 1953). Photographer, writer, artist, have gathered at the exhibition Modus vivendi the work of the last 30 years. Art is the way of living, or more precisely, the manners, that will leave you in any way other than the cold.

Julio Cortázar has a story, La baba del Diablo, in which Roberto Míchel, Franco-Chilean, translator and hobby photographer appeared in his hours. On the street he has accidentally seen a couple, as a group of friends, a teenager walking around with his dog or a cheerful family could see. But he's caught the couple -- or he's caught her, who knows -- and he's sitting there on the pretil, preparing almost unknowingly a scenic camera. During the departure, however, Michel will draw in detail the life and miracles of the couple throughout their life. Translation of Jon Alonso: “I’m not describing anything, I’m just trying to understand.”

It's a little bit what happens to some of Sophie Street's most well-known works: for example, when he photographes different men in foreign cities; for example, when he invites friends and acquaintances to his bed and then portray them sleeping; for example, when unknown people start to continue on the street without any previous strategy for the simple fact of following. It was his first job, in 1978. “I had nothing better to do. I was sick of being bored. In the end I understood that I was following.” People liked the photos. Now he exposes in Barcelona and Buenos Aires.

Some have called him voyeur. Others have called him a exhibitionist. Voyeur and the exhibitionist, even if both have said so at the same time. He doesn't have any of them. At least not more than everyone else. The use of supposedly autobiographical means has never prevented the construction of an artistic discourse. On the contrary, he said in some interview: “When I use my life it is not my life, it is a work hanging on the wall. What interests me is poetry that comes from everyday life.” Because the work of Calle has nothing to do with intimacy: “Whoever thinks he knows everything about me is totally wrong. My work is born from my intimacy, yes, but it never makes it visible. In addition, everyone forgets that half of my projects don’t talk about me, but about others.”

Within those limits, or rather within those limits, there are many Street plays. In short, the most important thing: Prenez soin de vous, 2007. The artist received an email from her partner in which the man told her that she had broken her relationship with her partner. “Take care of yourself,” he gave the end. She decided to take care of her not short, not lazily, and she passed it on to 107 women for each to interpret her text, including judges, diviners, style correctors and secret service police. The answer of the sexologist is: “I see no reason to take antidepressant pills. An evil fact can hurt, but the solution is not chemical.” The result, however, is spectacular, and puts you in doubt, in what cases, the use of email.

The point is that the work of Calle is situated in the field of experience. In one's own or another's experience. It can be the lived or the told, the real or the fictional, the direct or the deferred, the past or the future, the dreamed or desired. And that has led to art simulacro and appearance, seduction and gaze, fiction and memories, intrigue, espionage, persecution and deception, perseverance and perseverance, gaze and gaze. Calleja is the archaeology of the present and his workshop is the street.

Who is Sophie Street

The author of stories, faiseuse d’histoires, was called by the writer Herve Guibert. But who exactly is the woman who appears in so many pictures so differently? An actor playing a role? An artist in the representation of a character? Artist disguised as someone else? The artist in his interpretation? Or the artist at every moment, as such?

A character from the novel Leviatan by Paul Auster, Maria Turner, seems to be the secret of artist Sophie Calle: “He was an artist, but his work had nothing to do with the realization of the works that we normally define as art. Some said he was a photographer, others called him a conceptualist, for others he was a writer, but none of those definitions is accurate, and ultimately I think you can't classify in any way. His work was too absurd to classify people in certain media or disciplines. An idea appropriated it, worked on projects, there were concrete results that could be shown in art galleries, but that activity was not born from a desire to do as much art, but to obey its obsessions, to live its life as it would.” “It’s not me,” he once confessed Calle; “I am much crazier.”

You've been asked if she ever does feminist art. “There has been no claim in my work.” However, experts recognize that women have been discovered in art. Not just him, of course. But they invalidated the traditional passive role of female music, created a hitherto unknown model that went beyond the polarization of the mother and prostitution, turned their backs on the most prominent genres, painting and sculpture, hugging photography, video-creation or performance. “However, when you tell me, it’s a compliment to me.”

Street appears buying a burial in a documentary about her, Bolinas, in California. However, if you have not talked more about absence, loss, lack than death. As if that character in that tale of Cortázar said: “I’m not describing anything, I just try to understand it.”

This text comes two years later, but the calamities of drunks are like this. A surprising surprise happened in San Fermín Txikito: I met Maite Ciganda Azcarate, an art restorer and friend of a friend. That night he told me that he had been arranging two figures that could be... [+]

On Monday afternoon, I had already planned two documentaries carried out in the Basque Country. I am not particularly fond of documentaries, but Zinemaldia is often a good opportunity to set aside habits and traditions. I decided on the Pello Gutierrez Peñalba Replica a week... [+]