The musical feeling of the prisoners of the Great War

- The Berlin Museum of Ethnology has recently revealed a treasure trove of the Basques. Some of the thousands of recordings that are kept in this house during the First World War are in Basque. In the song you can hear the voices of the Basques who were imprisoned in that war. They are not the oldest recordings in Euskera, but the voices that were captured in the midst of the Great War are an exceptional witness to the harsh era.

During the Great War (1914-1918), they were held by soldiers from all over the world in the German prison camps, as the participating states led to the fighting of thousands of men from their colonies. These spaces were laboratories for the Germans, who experimented with prisoners in many camps, as well as in ethnological and musicological research.

Some of this information has now been visualized by the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin, in an exhibition open until April: photographs in the enclosures, objects and even sound files of the time, among them several specimens sung by Basques. So, I've seen a Lili, Gernikako Arbola, the beautiful star Adios, who were recorded in wax sheets a hundred years ago, from Ziburu to Sararat, there's an opportunity to hear songs that introduced me to the Atharratze Palace and beneath the Earth, sung from the mouth of the Basques.

Songs are not the oldest in Euskera that we know. Before, in 1900, Dr. Azoulay had performed phonographic recordings. These were found at the Museum of Anthropology in Paris by the Gasteiztarra translator Inaxio López de Arana. The recordings made by Rudolf Trebische in 1913 in the Basque Country, which collected songs, stories, stories and anecdotes from all the Basque dialects, among them the first recording of the theme Gernikako Arbola, are well known.

So what characterizes the wax sheets of the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin? Context. It is the voice of the Basque prisoners, away from their homeland, who are heard in the midst of a war that revolutionized Europe from the top down.

Berlin to Leningrad and return

At the beginning of the 20th century, the invention of Thomas Edison, the phonograph, had made a journey in which the waves were turned into vibrations. Coinciding with the Great War, Berlin school professor Wilhelm Doegen intended to record the languages and music of the captivity fields, given their diversity. In 1915, the Phonographic Commission was created in Berlin for this purpose and researchers started work (see table on page 7). Thus, songs and voices received between December 1916 and December 1918 were recorded in 1,651 wax discs. Songs and music in 1,031 wax sheets. In 1920 the organization was dissolved and the collection was divided into different supports: plates and discs.

The wax discs are currently in the Lautarchiv Sound Archive, under the responsibility of the University of Humboldt. After the First World War, leaflets about these discs began to be published in Berlin, including the phonetic transcriptions of songs and voices in Basque by the philologist Karl Bouda. The ethnographer José María Etxeberria published in 2008 the relationship and transcription of these songs, in the book Recordings in Euskera 1913-1917. Specifically, there are almost two dozen records; according to Etxeberria, Bouda also had news of more records, but “probably these records and other materials kept at the Berlin Institute of Phonetics were destroyed during the Second World War.”

The fate of the wax sheets was different. This collection, which initially remained in the Phonographic Archive, was transferred to the Soviet Union during the Second World War, to Leningrad, to East Berlin (DDR) in 1960 and returned to the Berlin Ethnological Museum in 1991. Eight years later, UNESCO declared Memory of the World to this collection containing about 30,000 plates. Among them there are 34 chapas that we had not known so far and that brought at least 75 songs in Euskera.

Two-minute sound witnesses

Each of the 34 sheets in Euskera lasts approximately 2 minutes. At this time, a song is sometimes recorded, sometimes two or three short songs. In general, no whole songs have been recorded, one stanza of the song, sometimes two. Beautiful voices and those who have become accustomed to singing are appreciated. In most cases, they act individually, but there are two in two, like they're singing bertsos, and songs that they sing as a canon. There is no song or verse that explains the situation of the prisoners. Listening to the corpus of all songs in their entirety and knowing under what circumstances they have been created, you see them as a second message: you can interpret them as wanting to express that they are captive.

Members of the musicology section of the Ethnological Museum of Berlin created a research project in 2012. They started to prepare and digitize the wax sheets so that experts and stakeholders can collect this music. Over the years and after the changes in place, many sheets were deteriorated. They also deteriorate whenever plates are used, because wax is a very soft material. Fortunately, some red iron negatives were already made in 1991. Of these, the project ones have made sheets again to be able to digitize the music recorded in them. They have already done the negatives of all the sheets through a galvanized procedure. On 27 November 2014, two project members announced at the conference that they will not hang these songs on the network, but will be transmitted to stakeholders and experts.

Euskal Kultur Erakundea (EKE) has a copy of the recordings, as it has signed an agreement with the Museum of Ethnology of Berlin to use the material for scientific purposes. According to his colleague Maite Deliarte, he has also recently been sent supplementary material from Berlin, with more detailed information on the recordings and singers, which are yet to be explored. According to Deliart's presentation report for EKE, the voices of at least three prisoners and the Euskalkis they use are Sulatino and Labortano; most songs are popular. There are some items from the collection of legislator Salaberri Mauletar, as well as writings known or collected by Azkue in the popular Vascon basket, such as the Gernikako Arbola of Iparragirre is not missing.

“The music of the Basques is special”

Romanist Hermann Urtel was one of the members of the Phonographic Commission. At the end of the war he wrote in the book Unter fremden Völker on Basque prisoners: “In the prison camps of the French, the greatest interest occurred in the time that that unique people, the people of Iberian origin [restvolk], who in the last century have had a constant dedication from scientists. (...) After seeing hundreds of delegates in the prison camps, a uniform ‘type’ cannot be recognised. They looked small, flexible, crawled and alive, but big, even silent back figures. (...) We limited ourselves to the representatives of the three main French dialects, the Labortans, the Bajonavarras and the Sulatins.” It is a pity that Urtel does not have a ‘type’ of the south in the camps in order to conduct a complete investigation of the Basques.

The committee also recorded Basque songs and stories: “We have a beautiful collection of songs and stories from the French Basques,” says Urfabric, “the best is from Salaberri. (...) The music of the Basques is special. A real Basque song is soon recognised as its origin; these melodies move in small melodic intervals that seem to have no relationship with the songs of other European countries, except the Albanian songs.”

Did they necessarily sing?

It's not easy to know how prisoners were chosen to sing in front of the phonograph. Urtel observed the prisoners who spoke in the Romanesque languages. Most of the Romanesque peoples in the Great War were considered enemies of the Germans, and I expected to find in the camps of the soldiers prisoners “many materials” that knew their language well. According to the expert, the captives were satisfied with the projects of the members of the Commission, no one refused to record, up to a maximum number of people expressing shame at the recorder. In general, they were chosen by their origin or by their skills, in a second step, both singers and speakers were asked to write the text of the song or of history in each one's dialect. As for the paper text, the experts prepared it together with the prisoners and then wrote the fonic transcript. This paper text was the one they had to repeat in front of the recorder, singing or saying.

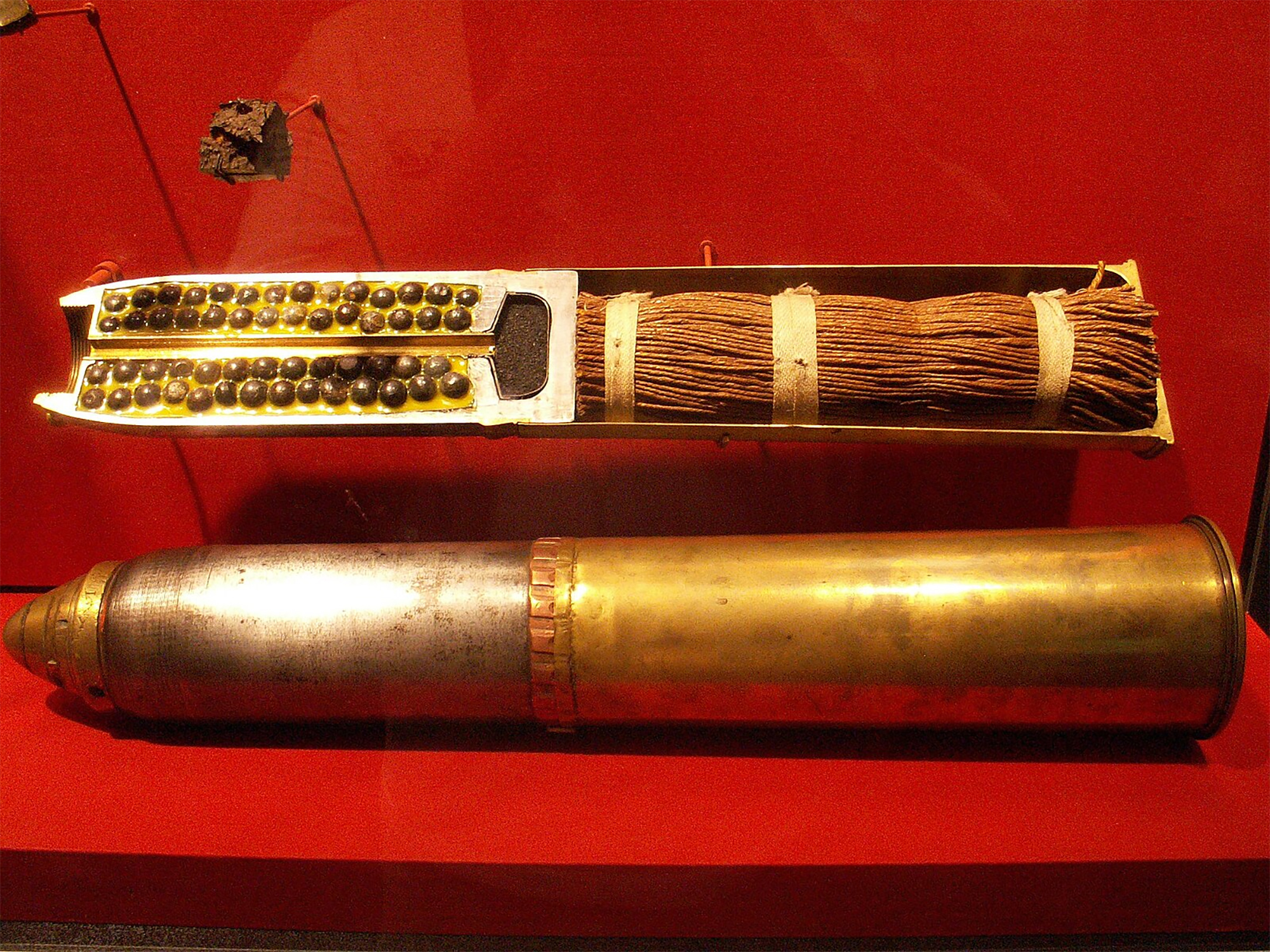

It appears that Urtel was present in the recording of several Basque songs along with George Schüneman, who was one of them. The second was the one that recorded all the Commission's sheets. Schünemann was a musicologist and was named responsible for recording music in the prison camps. He used a phonograph of the Edison brand for recordings. These phonographs kept the sounds in wax sheets. The technique for storing wax sheets was easier and easier to handle than the disc technique. So when Schünemann was addressing the prison camps, he only needed the help of a translator.

But there's hardly any transcription of songs. If they were lost or never done, we don't know. “It’s striking how little researchers who worked in prison camps created in their areas of knowledge,” says cultural scientist Monique Scheer in his 2010 article on this topic (Captive Voices: Phonographic Recordings in the German and Austrian ₡-of-War Camps of World War I) Of these recordings, only Schünemann published his “Habilitation” –2. doctorate – 1923.

In his writings, Schünemann noted that the prisoners were happy to hear their voice and that sometimes the prisoners also worked as translators and proposed to other colleagues to sing. Edison’s phonograph allowed the needle to be changed and heard after the recordings. To dissuade this new instrument, the recordings of prisoners were often immediately heard. Participation in this task involved the liberation of forced labor in the enclosure. They offered cigarettes to those who didn't want to sing. The recordings were usually made in the rooms enabled for this purpose, in order to obtain the best sound quality. In the rooms there were charcoal stoves and vigilantes who guarded the prisoners.

Identities and power relations

In most of the battalions in their armies, soldiers were classified according to their origin. When the prisoners ' soldiers kept their uniforms, it was clear that this was a military classification. These prisoners were deprived of all signs of identity that were neither military nor ethnic. From one day to the next they were forced to live in the “multicultural” situation of the areas. Basque soldiers were in the Rottleberod (Sachsen-Anhalt) area at the time of recording. The soldiers who were imprisoned in that area had to work in the sawmill.

The Basque singers in the recordings were soldiers who had been in prison for years, or perhaps more. We still don't know if they survived the tragedy, or what the survivors did at the end of the war. They represented all Basque soldiers who had participated in the Great War, at the same time as free people living in private life before the war.

There are still many unanswered questions. The research carried out from now on will serve to take steps in the process of elaborating or clarifying the historical memory of the Basques. On the other hand, recordings should take account of the power relationship between Basque prisoners and German experts, otherwise there is a risk of repeating the fantasy of the egalitarian situation in which they were held.

Philadelphia, USA, 11 July 1838. John Wanamaker is born, an entrepreneur who will then have a great influence on the marketing world. He started working in the commercial area with his brother-in-law at the age of 22. They both opened a store and the business gradually grew.

In... [+]

Wu Ming literatur kolektiboaren Proletkult (2018) “objektu narratibo” berriak sozialismoa eta zientzia fikzioa lotzen ditu, Sobiet Batasuneko zientzia fikzio klasikoaren aitzindari izan zen Izar gorria (1908) nobela eta haren egile Aleksandr Bogdanov boltxebikearen... [+]

Sobietar Batasuna, 1920ko azaroaren 18a. Sobieten Gobernu Zentralak abortua legeztatzeko dekretua onartu zuen, historian lehenengoz. Handik aurrera, librea izateaz gain, doakoa ere izango zen. Urte batzuetan behintzat.

Moskuko Plaza Gorriaren izena nondik datorren pentsatzean bi aukera bururatu ohi zaizkigu...

Krimeako konkista zuzendu zuen militarrak, Ukrainako gobernadore Grigori Potemkinek (1739-1791) Katalina II.a erreginari aurkeztu zizkion herri idilikoak faltsuak omen ziren. Hortik dator “Potemkin herria” esamoldea.