Prison policy that has brought revenge to this day

- There are currently about 375 political prisoners in 40 Spanish prisons – another 97 in France. 25 in prison.– At one time it was only necessary to move away from ETA for the means of reinsertion. In the last decade conditions have become very hardened. After the cessation of ETA, pp has turned prison policy into an instrument to condition revenge and the peace process.

Following the cease-fire in Lizarra-Garazi, ETA killed 43 people in the years 2000, 2001 and 2002. Nor was the State’s response a joke, and, in addition to the illegalisations against the Abertzale left, the position against the Basque political prisoners was greatly hardened, especially by the legislative changes carried out in 2003. The then Minister of Justice (pp), José María Michavila, explained: “It will be a decisive instrument to end terrorism and bring justice to the victims, as the firm and unabated use of the Constitution and the Law is the shortest way to end ETA.”

The truth is that the Spanish Government has been hardening prison policy for some time with legal reforms. The changes were carried out in three major movements starting in the mid-1990s. The reform of the prison regulations, carried out in 1996, tightened the attenuation of previous sentences and in 2003 two substantial reforms were carried out: on the one hand, to tighten the penalties for reform of the Penal Code and, on the other, a centralised system of control of prison sentences by the courts was established. Until then, the monitoring of prison sentences was carried out from the territorial courts where the prison was, and from 2003 onwards, the monitoring of Basque prisoners would be centralized in Madrid with the creation of the Central Court of Prison Surveillance. To the National Court, but for the surveillance of prison sentences.

30 to 40 years

The most important change in 2003 was the tightening of prison sentences, until then increasing to 40 years the maximum penalty of 30 years, many of which were sentenced to more than 80 years in prison, in the case of Basque prisoners. The annual calculation of the penalty to be applied to benefit from any prison specified the consideration of the total penalty of these prisoners. In other words, if a prisoner has four sentences of 10, 15, 30 and 40 years, he would add a total of 105 years and would have to depart from that total amount in order to achieve any kind of attenuation of the sentence, which would prevent access to prison benefits.

Until then, if a prisoner had been in prison for 30 years, and through revisions or mortgages he was able to alleviate 10 years, he was taken from those 30 and 20 years later to the streets. Under the new law, the 105-year-old prisoner would be reduced to 10 and the prison sentence would continue for 95 years. The legal reform itself clearly explained its spirit: “Under this rule, in the event of possible penalties of 100, 200 or 300 years, the offender will in practice fully and effectively comply with the maximum penalty limit.” In practice, the 40-year penalty became a lifelong penalty.

But many other measures were also put in place, such as the conditions for the prisoner to obtain the third grade. The Basque prisoners are in the first and second grades, with the toughest conditions. With the third grade, the prisoner can go out on the street with several days of leave, go from day to work and from night in prison, or enjoy parole by serving two-thirds or three-quarters of the sentence.

This reform set out the conditions that have now become popular in order to obtain the third grade, which is essential for dismissal: the willingness to pay for civil liabilities, the clear position of cessation of armed activity, the active cooperation of the security forces in the fight against ETA or the forgiveness of victims. This does not mean that every prisoner who accepts reinsertion measures has been asked for all this, since in each case the law is interpreted with the desired flexibility. This reform was approved by the Congress of Deputies in March 2003 with the support of pp, PSOE, CIU and Coalition Canaria.

The law, however, cannot be applied retroactively and there was a large group of ETA prisoners sentenced to 30 years in prison, sentenced under the 1973 Penal Code, who were gradually released for 16, 18 or 20 years. They were names that the Spanish media had danced madly and although it was sold to the public that these ethnic groups would rot in jail, the known names either went to the streets or were going to leave.

Basically, these “quick” layoffs were produced because the 1973 Penal Code was much more flexible to alleviate the penalty, as the Spanish Constitution clearly states that the objective of the prison is to reintegrate. The Spanish Government, which has been outraged by this issue for years, adopted almost a decade earlier a number of measures to tighten up the rules or ludogisms of penalties – cuts in years of imprisonment that are achieved for reasons of study, work, etc. Well before the aforementioned reform in 2003, the Spanish Government processed in 1996 a reform of the prison regulations to reduce the effects of ludogismus.

‘Parot Doctrine’

With the 1996 reform, mortgages were reduced and penalties and their control were tightened in 2003. This, however, did not solve the situation of prisoners who were prepared to serve a 30-year prison sentence and should therefore be released if they did not do anything. What do you do to make them 30 full years old? The Spanish Justice invents the Parot doctrine through a ruling issued in 2006 by the Supreme Court.

In response to an appeal lodged by the prisoner Unai Parot, the Supreme agreed that the reduction of years for mortgages would not be made from a maximum penalty of 30 years, but from each of the penalties, thus ensuring the achievement of 30 full years. –Less than 30 to 10 to the street with 20, less than 1,000 to 10 years there are still 990.

The spirit set out in the 2003 reforms to reduce prison benefits led to a change in the provision of punishment, which has resulted in many prisoners having served 30 years in prison or close proximity. In response to the appeal lodged by the Donostian dam Inés del Río, in 2013 the Court of Strasbourg declared the Parot doctrine illegal and, as a result, some 55 Basque prisoners were slowly coming to the streets.

Article 100.2

According to the Spanish Penal Code, it is therefore virtually impossible for those sentenced to more than 40 years of age to be released on parole before the age of 30. But there is no regulation that perpetuates something if the authorities so wish, and that is what Article 100.2 of the Prison Rules is for. According to this, the prison itself can flexibly read the situation of a prisoner and classify him to the extent that he wins, as well as make a confusing degree. Former Civil Guard General Enrique Rodríguez Galindo, former Interior Secretary Rafael Vera or former Civil Guard General Luis Roldán emerged. And so have many Basque prisoners who are sick. The jail proposes the grade and the judge may or may not accept it, but if the government wants, the prisoner leaves.

Therefore, if the state so wishes, it has a lot of measures to liberate the prisoners individually, either by means of legal reforms or by respecting the law it has. In order to put an end to a policy of dispersion that has caused one of the greatest damage to prisoners and their families, for example, the Spanish Government does not need a change of law or a judicial permit, just a will.

It could also be a consequence of the “technical negotiation” between ETA and the government – weapons in exchange for prisoners – but there too ETA has lost opportunities, as in the negotiations in Algiers, Lizarra-Garazi and Loiola. And now what? Now, the key lies in the capacity for pressure and mobilization of Basque society.

Joseba Azkarraga EAJren senataria zen 1980ko hamarkadaren hasieran bere alderdiak eta Jose Barrionuevo Espainiako Gobernuko Barne ministroak (PSOE) ETAko presoen birgizarteratze plan bat bideratu zutenean. ‘Azkarraga bidea’ moduan ere ezagutu zen eta batez ere ETApm-ko presoek heldu zioten eskaintzari. Gerora, Joseba Azkarragak hainbat kargu izan ditu EAn eta Eusko Jaurlaritzan, Ibarretxe lehendakariaren azken Gobernuan Justizia sailburu.

1980ko hamarkadaren hasieran birgizarteratze prozesu hura bultzatu zenutenean, zer baldintza eskatzen zitzaien presoei?

Gaur egun eskatzen diren horietako bat ere ez. Egindako minaren aitorpenarekin hasi ziren, baina gero barkamen eskaera egitea aipatu da, bere garaian egindakoa gaizki zegoela onartzea… Garai hartan, ETA jardun betean zegoenean, bakarrik eskatu zitzaien sinatzea agiri bat non esaten zen presoak beraien ideologia soilik modu baketsuan defenditzeko konpromisoa hartzen zutela. Kito.

Nola konparatuko zenuke gaur egun eskatzen zaienarekin?

Ez du zerikusirik, are gehiago kontuan hartuta ETAk bere jarrera armatua utzi duela eta iragarri duela ez dela hartara itzuliko. Horrek ez du zentzurik. Gaur egungo espetxe politikaren ezaugarri nagusia mendekua da eta hori legearen edukiaren aurkakoa da. Legeak argi esaten du, adibidez, preso guztiek dutela eskubidea euren zigorra haien bizilekutik ahalik eta gertuen betetzeko eta hori da presoek eta haien senitartekoek eskatzen dutena.

Zer egin dezake Eusko Jaurlaritzak?

Jaurlaritzak ez du espetxe eskumenik eta, beraz, garatu ahal duen edozein proiektuk beti egingo du topo Espainiako Gobernuaren jarrerarekin. Hitzeman proiektuak, esaterako, izan dezake gauza onik, baina ez du eraginkortasunik. Nik gaiarekiko konpromiso publiko handiagoa eskatuko nioke, eta Espainiako Gobernuarekiko tinkotasun handiagoa, ezin da beti erantzukizuna ETAren gainean jarri, Espainiako Gobernuari eskatu gabe legea bete dezala. Ez da ulergarria batzuek bukatutzat ematea biolentziaren arazoa, ondorioak konpondu gabe daudenean; eta bai, biktimena da ondorio oinarrizkoena, baina baita ere presoena. Hori konpondu gabe, inork ezin du bukatutzat eman herri honetan bizi izan dugun arazoa.

Eusko Jaurlaritzak iraganaren kritika eskatzen die presoei. Zein neurritan da beharrezkoa espetxe onurak jasotzeko?

Legeak ez du horrelakorik eskatzen, uste dut ezin dela halakorik eskatu. Barkamena behartuta eskatzeak, adibidez, ez du ezertarako balio. Niri oso ongi iruditzen zait presoek barkamena eskatzea, baina legea betetzeko barkamena eskatzea astakeria iruditzen zait.

Nola ikusten duzu euskal gizartea presoen gaiarekiko?

Badira lanean ari diren hainbat talde, nik laguntzen dudan Sare adibidez. Euskal gizartea saretu nahi duen herritarren mugimendua da Sare. Ideologikoki pertsona desberdinak gara, baina uste dugu presoen eskubideak ere errespetatuak izan behar dutela. Uste dut konfiantza handiagoa izan behar dugula gizarte zibilak duen indarrean, eta nik behintzat konfiantza handia dut.

2013ko abenduan Euskal Preso Politikoen Kolektiboak erabaki historikoa hartu zuen: haien kaleratzea lege-baliabideak onartuta egitea, “horrek inplizituki zigorraren onarpena” ekarri arren. Konpromiso indibidualak hartzeko jarrera erakusten zen agiri bidez, beti ere “prozesu orokor batean” eta “denbora zuhur batean”. ETAk borroka armatua utzi izana ontzat eman zen eta “Euskal Herriaren askatasunaren aldeko borroka aurrerantzean bide eta molde politiko eta demokratikoetatik” egitea ere bai.

Ordura arte EPPK-k ez zuen Espainiako justiziak jarritako zigorrik onartzen eta kaleratzeko irtenbide kolektiboak bakarrik onesten zituen. 2013ra arte kolektibo honek –preso gaixoen salbuespenarekin– ez zuen espetxe onurarik eskatzen eta, ondorioz, espetxe onura asko galtzen zituen, batez ere hirugarren graduarekin lotutakoak, esaterako baimenekin ateratzea edo baldintzapeko askatasunean kaleratzea. Presoek ez zuten eskatzen, baina zegokiena emanez gero, hartu egiten zuten. Hartutako onuren artean legez zegokien espetxe urte murrizketak zeuden.

Erabaki honen ondorioz, 2014an zehar bi mugimendu handi egin dituzte EPPK-ko presoek. Batetik, espetxe agintaritzaren aurrean legez dagozkien eskubideak eskatu dituzte bakarka, bai Euskal Herriratzeko eskatuz eta baita dagozkien bestelako onurak ere. Espetxe Agintaritzak muzin egin die eskatutako onurei eta ondorioz, presoen bigarren mugimendua etorri da, ukatutako eskaera horiek justiziaren esparrura bideratzea. Horretan da prozesua orain, Espetxe Zaintzarako Epaitegi Zentralaren erantzunaren zain. Esperantza urria da, borondate politikorik gabe nekez izango baita aldaketarik.

PPk eta PSOEk 2003ko Zigor Kodean diren baldintzak betetzea eskatzen diete presoei, besteak beste kalte-ordainak ordaintzeko borondatea agertzea, ETAtik aldentzea, egindakoagatik damua agertzea eta biktimei barkamena eskatzea. Egia esan, ez dago argi zehatz-mehatz zer eskatzen den, legeaz egindako interpretazioaren arabera eta borondate politikoaren arabera eskaerak asko alda daitezke eta. Eusko Jaurlaritzatik ere iraganaren azterketa kritikoa eskatzen zaie presoei, egindako mina eta kaltea injustua izan dela aitortzea. EPPK-k iazko abenduko agirian onartu zuen egindako kaltea eta mina, eta konponbide prozesuan hortaz hitz egiteko prestutasuna agertu zuen. Horrez gain, Hitzeman birgizarteratze programa aurkeztu zuen iragan urrian Jonan Fernandezek zuzentzen duen Bake eta Bizikidetza Idazkaritzak, baina EH Bilduk oso kritika gogorra egin zion, haren ustez programak zilegi egiten duelako egungo salbuespenezko espetxe politika.

What surprised you the most when you left jail? I've been asked many times in the last year and a half.

See that the streets of Bilbao are full of tourists and dogs with two legs, for example? Or the changes in the political situation? The first one has tired me and annoyed me... [+]

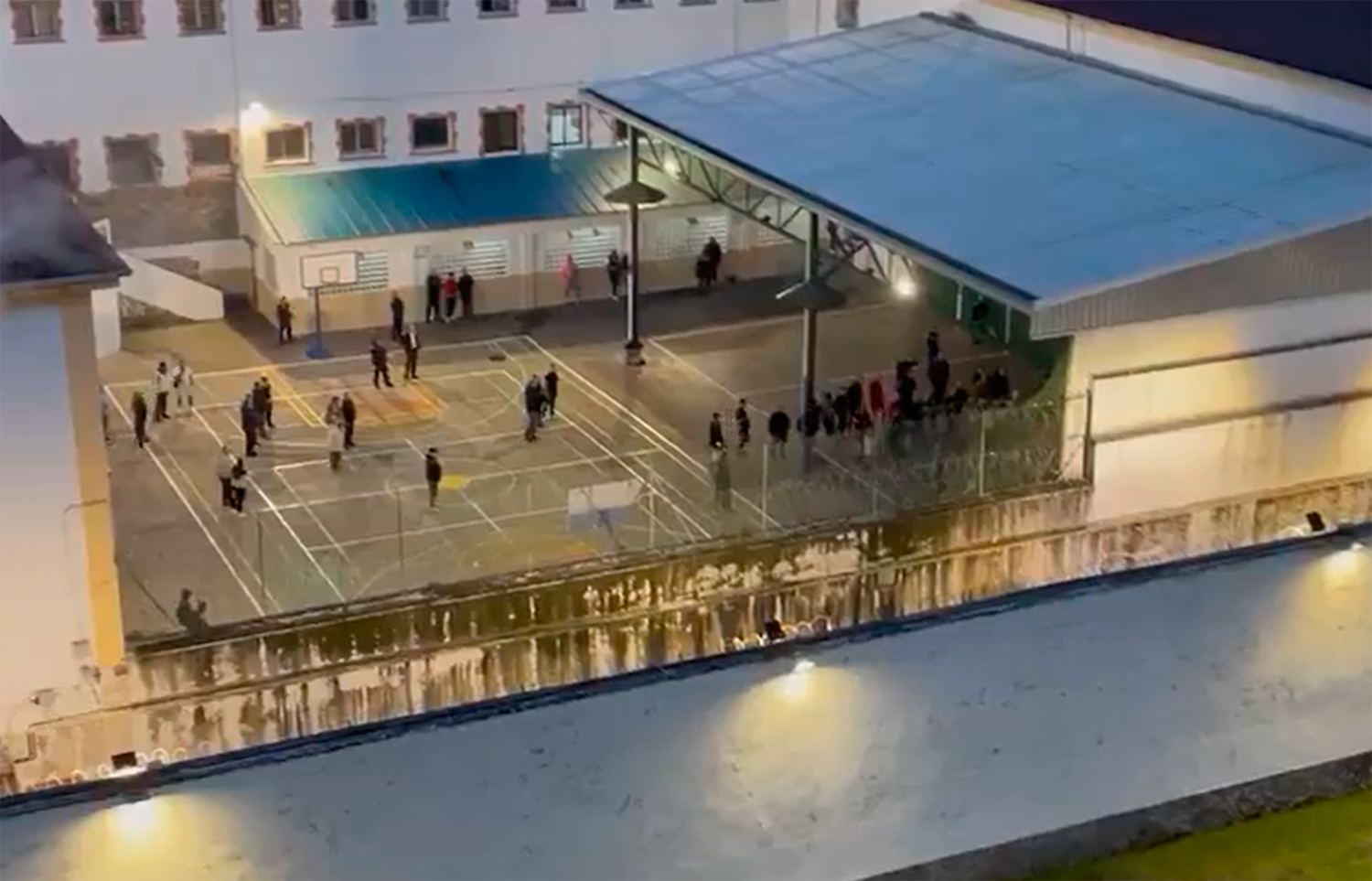

Since we were transferred to Euskal Herria from the prisons of the Spanish State, in the prison of Zaballa we have found many deficiencies in the field of communication. We have fewer and shorter face-to-face contacts, we have had to make visits to the speaker in poor technical... [+]