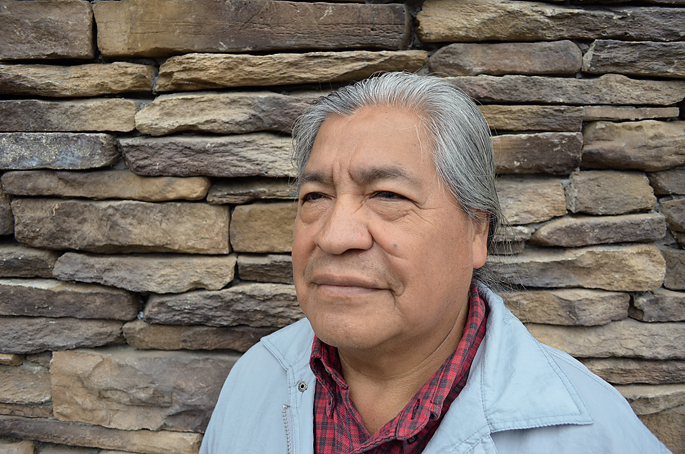

"Thought does not change until it does not depart from each other's culture, language and spirituality"

- Lix López has met indigenous groups from all over the world thanks to the work done for the indigenous peoples of Canada. It has travelled a long way back and forth through the mountains of Central America, the territory of the Sami and from there to North America. He has learned a lot and has a lot to teach and has not stopped going to Vancouver University (Canada). But not to give lessons, but to cultivate the land.

Lix López is maia and says: “For thousands of years Maya civilization has cultivated the land. Our ancestors have sown the earth, and I also try to keep it.” It is dedicated to the vegetable garden created by Mayan families in Auzolan. Start talking about the importance of corn, beans and pumpkin, but then braid another triple: Culture, language and spirituality.

Where are you from?

I was born in the town called Ixtahuacan, in Mayan territory. It is officially Guatemala and is known as San Ildefonso de Ixtahuacán. Our grandparents didn't speak Spanish; my mother just did a little bit because I had never gone to school; my father, yes, my father was a teacher of castillanisation in church school. As a young man, because he spoke a little Spanish, the priest proposed to help him in the parish and thanks to that I have been able to study. At home, we only talked about the Mam language.

Wasn't Spanish and the media coming to them?

The media? It's the first time I see a phone at age fourteen! We were taught Spanish at church school. Above all, we were going to learn how to write, read and speak in Spanish. There was also a national school, but it was for the ladinos, we call them the ones who are not. There were very few ladies and they didn't cultivate the land, they were sinks, teachers, pharmacists...

But you learned more than Spanish at school.

Yes, my father wanted me to continue studying, so I went to jail so I didn't pay for school and livelihood. When I finished high school, I realized I didn't want to be a cleric, and I went on to study marketing at the University of Guatemala.

What was it like to get into college for a Maya in 1969?

We were alone three or four at the Catholic University, probably there were other specimens at the National University. The same priest who employed my father helped me get the scholarship, you know, those have their contacts. Once in school, they talked about languages, and I told them I spoke two languages. My peers started asking me: "Oh, yeah? And what's the second one, French? English?” They didn't know that the breast existed, and they were the children of the economic elite of the country.

What was the relationship with colleagues like?

They didn't abandon me. I was not politicized then, but the awareness of being different was internalized from the children: we were the Mayans; and they, the ladinos.

At the end of my marketing studies, I got a scholarship to Belgium thanks to a Flemish missionary and travelled to Europe. I spent six months studying French and in September I entered the University of Leuven as a sociology student.

What did you think of Europe?

Everything was new, but in his youth he is very able to adapt... The Belgians, although they have also been colonizers, treated me very well. I was exotic to them and every weekend I was invited by a family. For them it was like having a Hindu at a Western's house, and I knew it, but on the other hand, I was sitting at their table. And I wondered. “Despite being white, they treat me well and respect me, but the Guatemalan thieves do not. Why?” I started looking at things on the other side. And then what happened not only changed my mind, but also my direction in my life: In northern Sweden, in the territory of the Samians, the Second Council of Indigenous Countries. I learned that they were going to hold the General Assembly. I didn't doubt

It took me three days to get to Kiruna by train and then to Stockholm by car.

And what did you find in Kiruna?

Indigenous people around the world: Central and South America, Australians, Maorians, North Americans, Samias... My eyes opened. The Bolivian people included me in their delegation. I didn't have most of the things that they were talking about there, but I realized there was a sense of identification. We were all in the same situation: colonized. That was what caused, and what provoked, the unity of the indigenous countries. There I also met the contacts that would lead me to Canada.

How was the trip to Canada?

I had a plan to go back to Guatemala when I finished my studies in Belgium, but before I wanted to get to know North America. When I arrived in New York, I bought a $100 ticket that allowed me to travel as long as I wanted at the Greyhound bus company. When I got to the west coast, I went to the office of the primitive villages in Vancouver and volunteered. There I met the late George Manuel, founder and president of the World Council of Indigenous Countries. He said to me: “I know you’ve studied in Europe, in college, but if you start working with us it will be a further grade. With us you will learn what you will not be given in college.” I was hired as a translator for relations with other indigenous countries in America. I left the bus and started traveling by plane to meet the indigenous people. I even started an inner journey for myself.

What do you think of Canada's behaviour towards its countries of origin?

The Government and society in general have realised the problems of the people of origin. And Ottawa is making an effort. Effort to wash your face and unmask it. Reconciliation as a symbolic gesture is fine, but it does not resolve the damage done to indigenous countries. They have been stripped of culture, languages and land. There are pacts, yes, but the government has adapted them to their liking. It's easy to say, but it's not enough. They continue to live in reservations. What head does store people in a piece of land? The distribution of tribes has been possible through an unequal distribution of money. On the other hand, there are indigenous Members but entry into this field of play will not solve the problems of the indigenous people. They have a robust bleached system and cannot go against the established.

So what's the way?

It is the indigenous countries themselves that have to fight. And for that, it's so important to reclaim culture, language and spirituality. If then the action is not based on those three, the policies of the past are repeated. The way of thinking does not change until it starts from culture, language and spirituality. These three are inseparable and form a foundation, but they are not paid attention. Before – and now also – more was said about land than about language. It is a mistake. There is, however, an awakening of indigenous peoples. I have faith in young people.

“Jatorrizko herrientzat lanean hasi ahala nire pentsamoldea errotik aldatzen hasi zen. Nire kultura berreskuratzeko premia sentitu nuen. Hizkuntza, urteetan hitz egin ez arren, ez nuen galdu, baina espiritualki... hori beste kontu bat zen. Nire buruari galdetu nion ea zertan jardun nintzen hainbeste urtetan katolizismoan. Hutsunea nabaritu nuen barnean. Ez nekien ezertxo ere maia espiritualitateari buruz, eta horren bila hasi nintzen: zeremoniatara joaten, zekitenei galdezka... prozesu luzea da. Orain dela hamairu urte bihurtu nintzen ajq’ij. Izen horrek esan nahi du: eguzkia ezagutzen dutenak. Ajq’ij izateko berezko sena behar da aurrena, eta gero hori lantzea. Egutegia ezagutzen dugu eta jendeari laguntzen diogu zeremonien bidez. Sendatu eta arbasoekin komunikatzeko dohaina dugu. Seguru nago Euskal Herrian ere badagoela gaitasun hori duen jendea. Energia hor dago, ez da desagertzen”.

Gobernuaren arabera jatorrizko 60 hizkuntza baino gehiago daude Kanadan. Oso gutxik iraungo dute, dozena-erdiak onenera. Lopezen arabera esperantza izpi bat dago hiztun kopuru handi samarra dutenentzat: cree, inuktitut, soto, mohawk, blackfoot eta anishnaabeg. Maia hizkuntzak ere asko dira, 30en bat, eta batzuek osasun hobexeagoa dute. “Guatemalan badira eskola elebidunak duela hogeiren bat urtetik. Horrek bakarrik ezin du hizkuntza mantendu ordea. Jendeak egin behar du ahalegina, eta horretarako kontzientzia politikoa behar da”.

Lau egunez idekia izanen den merkatu bat antolatzen du Plazara kooperatibak euskararen aldeko beste hamar bat eragilerekin –horien artean ARGIA–.