"We were brave young people, a spouse of a social situation"

- (Altzola-Elgoibar, 1933). He was ordained a priest in 1958. In 1968 he went underground, becoming a liberated member of ETA. Mogrovejon was arrested. Judged in the Burgos process with fifteen other members. He was in El Concordato prison in Zamora for seven years. He was released in 1977.

He has published the book Landan de Zamora with the help of the Intxorta Cultural Association 1937. According to him, he was released from the false 1977 amnesty. He was a professor of Euskera at the Public School until his retirement. Last year, after residing in Etxarri Aranatz for nineteen years, he returned to Eibar with María Luisa Ruiz Arana, a partner of the deceased.

How do you remember the Altzola neighborhood and childhood?

Small town of children. It's about how good and how bad small neighborhoods are. There was a lack of much that was happening in the great peoples, but there was a lot of mutual knowledge, solidarity. There were a lot of people coming to the spa, so there were a lot of Castilian speakers.

Your father had placed the ikurrina on the day of the inauguration of the Altzola Batzoki, before the 1936 war. His father had to go in front of him.

That is what we believe. I knew later that my brother, who was still three years old, told me. One of the countrymen said to his brother, “Your father put the ikurrina.” The national father came to the town and went to the front of the war, fleeing. He and others, jeltzales. One of those who remained was killed there, another was taken to the hospital and another was released by a "lord" of the people who had left his side. Many citizens were merged in Altzola.

After the war, would you study in Francoist National Schools?

Yes. We didn't sing Cara al Sol, but we had wood rifles and we marched through the patio. In winter we said “Miss Fries”, and he “parade, pin, bread, pin, bread”. Every day we put the flag of [Spain] on the school balcony. We were kids and we had fun, we struggled. That was a game for us. We were unaware of what had happened during the war.

My father was a worker. But I had learned.

Yes, my father told us stories in Basque. He had a lot of capacity, we received his stories naturally. Today I remember it with astonishment, I had an amazing ease of reading. We listened to our father in Gipuzkoan and in Biscayan, he used to use both mixed. Mendaro, Altzola and the Basque border of Elgoibar. The Basque Country of Altzola is like this. Then, as a young man, it helped me a lot, I made friends easily on both sides.

At thirteen, you went to the seminary. He got to know the seminars of Saturraran, Vitoria and San Sebastian. Why did you leave?

For my mother, my endearing madre.Era from Zaldibar, also from Euskaltzale. We were five brothers, three boys and two girls, I tercera.Antes that I was a priest was my older brother, he left him and my mother said to me: “Why aren’t you going?” I just remember the time of Saturraran. Then, speaking to friends, we remembered that there was a lot of discipline. We couldn't walk from two to two, just three to three. They did not accept friendship between two: They called us "Never two, at least three." If he sees two, punishment. We got the note down. I went to Vitoria when I was 17, when I was a kid. I studied philosophy and humanities, then in San Sebastian, the last year of philosophy and theology for four years.

And then you were a cure.

I was ordained a priest in Lourdes, it was a special year, the basilica there had just been built, so.

By then you would have some idea of what the Basque Country was, right?

Yes. When I was 18-20 years old, I found my father the book De Guernica to New York going through Berlin, by the lehendakari José Antonio Agirre. I read it with great curiosity. I didn't have much knowledge of patriotism, and it helped me a lot. I made my first serious reflections on the problem of the Basque Country. Next to the book, my father wore a small silver lauburu on his shield.

In 1954, Franco opened the seminar in San Sebastian. You were present. What was the atmosphere then?

Among seminarians, in a way, there was Basque nationalist sentiment. But you didn't notice that on the street. I remember Franco on the stage, pronounced a sermon, surrounded by soldiers. He passed through the hallway and around the words “Long live the Pope.” Roman Orbe, a Phalangist and professor of theology, proudly told us that he was a supporter of Franco. For the first time, I realized there was a kind of rejection of him. But the atmosphere was not political, we weren't talking about politics. So I had my first patriotic sensations out of home against the regime.

At the age of 25, you were a priest in the Marin district of Eskoriatza.

We were young, we had little experience, but it was a nice experience. The students were young and nationalism naturally resurfaced in the village. We worked the theater and the song, organized on my own. The Mass gave it in Latin and the doctrine and songs in Basque. After a while, the bishopric tended to change its location. They set out to go elsewhere, and I said no. In 1963, I agreed to go to the Azitain neighborhood of Eibar, I couldn't say no. The experiences were enriching, but now I realize that I was the master and master of the people. The cure was a terrible thing. I remember myself as a boy, and one of the elders of the village.

How did you re-enter ETA?

I didn't get into ETA for myself. I had a friend [the current couple, María Luisa], who asked me to take me to a group of friends from one place to another. He told me they were ETA members. From Eibar to Mondragon and take it. It was about 600. The car in question came to me in a rifle per hour.

I guess they were armed.

Yes, one of them, to keep things in sight, pulled out the gun and did a demonstration of that. It didn't make me feel.

Who were they?

Jokin Gorostidi, Javier Larena, Unai Dorronsoro and Teo Uriarte. Pottolo, mudito... I only knew the nicknames. ETA’s management was occasionally at María Luisa’s house.

You've also met Txabi Etxebarrieta.

Yes. Several times I took him by car. I had a rather pessimistic impression of Txabi. In the political debate, I was a very talkative, and I would take the bilbait-like aspect of it. Then I found out who I was. To what extent I was an ideologist and thinker ...

Subsequently, in 1968, Txabi Etxebarrieta was killed in Benta Aundi (Tolosa).

It was a tough time for us. Iñaki Sarasketa fell into the hands of the dogs and for fear of singing their names, Maria Luisa and I went to Barcelona. After a few days, after knowing that there was no movement in Eibar, we came back.

Soon after ETA murdered Meliton Manzanas. Historians have stated that the murder of Txabi Etxebarrieta “helped” Manzanas to take the step of dying. Do you have the same view?

Maybe. I don't know if it was for Txabi's murder. I think it had already been decided to kill Apples.

As a priest, how was the murder of Apples taken?

It was terribly hard for me and for everyone. Like the first draws. When ETA started stealing money from banks, people struggled to accept it. Maybe it was easier to accept Apples' death than to steal money. Obviously, when the other murders arrived, it was more difficult to accept. I was already in jail.

You were still in ETA.

After Txabi's death he was also a collaborator, legal, not a member of ETA. When I returned from Barcelona, I realized that the dogs followed me. Maria Luisa went underground, and then I was told if she wanted to join ETA. I said yes, but the decision was very difficult and difficult.

What is that moment like?

Years after I entered ETA, a friend told me: “I could also have entered ETA as well.” It was developed in one part according to the circumstances and it happened to me.

Who was your friend? Do you live?

Yes, but I won't tell him his name.

A priest is part of an armed group.What would the bishop think?

I don't know ... They would be scandalized in the church, of course. I entered the underground and meditated: "According to the doctrine of the Church, the entrance of a priest into an armed band is a contradiction of Christ. But I'm from this town, and I've made this choice. I looked at the church and thought, as a Christian: The Church has always taken up arms. The Roman emperor Constantine had great struggles with himself at the time of using violence. He had been presented with a cross. Well, me too. Christians had organized themselves into armed groups and maintained contact with Constantine. He was about to lose the war and Christians joined ella.En the Middle Ages there were also great struggles in the Church, armed. For example, the Church authorized the invasion of Navarre.

The history of our people...

Yes. The Church has been involved in violence throughout history. He blessed the National Uprising of 1936. Where were the Requetés of Navarra protected? The churches were places of organization of the uprising. Most holy wars and bishops stood on Franco's side. So such a scandal because some priests walked with the gun against the Francoists? What had I attacked Franco with a gun? In an armed group? Is this a contradiction? It's possible. But it has been that practice of the Church, mine also has to be understood within it. Mine and many others.

You were captured in Mogrovejo, in Santander, under the direction of ETA. You were tortured.

And in addition, with a terrible energy: “You are not a cure. The bishop is against you” to begin. They took me to San Sebastian and read to me what the bishop said on the first page of the Unit newspaper. The Bishop refuted what the newspaper had written. Jacinto Argaia was a bishop and defended me. He was a supporter of Franco, of course, but he played a very special role in the Burgos process, where he was murdered.

Tell us how you lived through the Burgos process.

We wanted to politicise the process. To turn the trial, to denounce it, to some extent to judge the Franco regime. Since today it seems amazing, but there are times in history... – It is difficult to explain why and why – in which the people rise. People were fed up with Franco, had been under dictatorship for many years. People were on the street, in the Basque Country and also in Spain. On the occasion of the Burgos process, the priests of the world moved in our favour. I know very well what Maria Luisa told him, he was in Paris. We were just brave young people, somehow we were cuddlers of a social situation.

What was the trial like?

We prepared it very well. When the judges were starting to speak, we would run them. My job was to “touch” the church. He wanted to look like a priest, a member of the armed gang, with a gun. We wanted to provoke that discussion among the priests. Of course, they didn't leave me, but I got a priest's dress up. I took a kind of priest's jacket and put the leaf in my pocket, in front of the judge. I had no intention of following the cure, but I started to argue. Weapons yes or no? Of course we did not manage to discuss it, but it was nice. My lawyer Ramón Camiña, from the PNV, asked me for a moment. “Would you recognize your gun?” I got up to point it out with my hand, and they all moved in the room. There was a lot of tension, and we liked it.

Then ETA was split: And V and VI. You VI.aren left.

This was my first important theoretical debate. Until then there had been no in-depth political discussion. Some have discussed it on our behalf, but no decisions are taken in the group, because there are no external documents. We later received a lot of information, a lot of reports of a lot of trends. My fundamental idea was this: “The working class Euskal Herria is either not really going to achieve freedom. Political independence does not liberate the people.” Armed struggle had no priority for me; independence could be achieved, but not the real freedom of the people. I thought that would not happen without the working class being liberating and free.

You have clearly agreed with your attitude.

In Zamora we had few controversies about the armed struggle, but we were asked to take the stand from the outside. The majority opinion was as follows: “We’ve read a lot of documents, but we don’t know the street environment. We have to be out to promote the debate. We’ll decide when we’re out.” I gave him the ETA accession VI.ari. I officially took the position.

Zamora's prison was special.

The Church had a great responsibility for what happened in Zamora. It was not just a state prison, but the Church Concordato was also involved.

Did you see the murder of Carrero Blanco?

Joy was general and we celebrated it. These things are relative, they have to be understood in the repression of Franco.

How did you live to be called Spanish?

You get used to it. “I chose that path and told someone that I wasn’t as patriot as I was.” And it's still the case today. That Euskal Herria had to own himself, but that he had to do so by joining other peoples.

And how do you think today?

That in order for the Basque Country to own itself, the first thing we have to do is to cultivate our own identity. I think we need independence in order to be able to take steps as a people. Times have changed. Seeing the power of Madrid, I have always thought that the armed struggle was not going to win. Lengthen the conflict, influence the people, but not win. I have never seen this possibility of defeating the state, but I recognise that the armed struggle has had a great impact on the country. The future will tell the impact that the struggles of the past three decades have had. “If it hadn’t been ETA we would be better,” some say. Others say that “we would not have the degree of sovereignty we have now or the attitude of the people in favour of sovereignty”. This dilemma cannot be measured at the moment. Having said that, I believe that those who have taken the path of ETA in recent years also have the right to choose that kind of struggle.

Apaiz nintzenean motorrez ibiltzen nintzen, eta gero kotxez ere bai. Garai hartan ez zen ohikoa. Liburuaren azala Jose Martin Urrutiak egin du (Txotxe), nire lagun minak. Kartzelako leihoa, motorra eta ihesa irudikatu ditu. Motorrez bizkor ibili ohi nintzen. Zamorako kartzelan zuloa egin genuen, baina halako batean txibatazoa izan zen eta ihesa zapuztu ziguten. Imajinazioa eta psikologia izugarri lantzen genituen. Zuloa aurkitu eta esan zidaten: “Ingeniaria ikasketak egin al dituzu?”. Batzuek zuloa egin bitartean, bestetzuek kartzelariak engainatzen zituzten. Xabier Amuriza lagunak bultzatu ninduen Zamorako Landan liburua idaztera. Ez nuen aparteko gogorik. Banuen ipuin bat idatzia, eta sari bat irabazia ere. Tunela nola egin genuen kontatzen duena. Xabierrek “segi, gehiago kontatu behar duzu” esan zidan. Eta hara, narrazio gehiago idatzi dut liburua egin arte. Xabierrena bultzada baino gehiago izan da, aholkuak eman dizkit. Bera eta bertan izan ginen guztiak gogoan ditut. Nikola Telleriarekin oroitzen naiz sarritan. Orain harritzen naiz, orduan ez nintzen jabetzen. 60 urterekin sartu baitzen borrokan. Preso politikoa, apaiza, langilea, euskaltzalea. Kartzelako bizi latza jasan zuen Nikola lagunak. Preso sartu berria gaixotu zen. Zein gaizki tratatu zuten! Erraz ahazten zaizkigu presoak.

Etxarri Aranatz [Nafarroa Garaia] herrian lagun asko egin genituen Maria Luisa lagunak eta biok. Presoen mundua hurbiletik segitu dugu, presoen familiarenak bereziki. Presoek atxiki duten indarrarekin harrituta nago. Askok arazo psikologikoak omen dituzte. Nola ez dauden erabat jota eta deuseztatuak pentsatzen dut nik. Batzuek 30 urte barruan egin dute. Bakarka, isolatuak, talde txikietan. Nondik atera dute indarra? Kanpoko berrien bonbardaketa jasaten dute. Hedabideetatik zabaltzen diren berrien nahasketa izugarria da. Informazioa partzialki eta modu txarrean iristen zaie. Taxuz eztabaidatzeko aukerarik ez dute izan. Baldintza horietan, horrenbeste urte preso pasa ostean –gure garaian hamar urte izugarria zen– horrela ateratzea. Denetarik dago jakina, denak ez daude osasunez ondo, baina nik asko gogotsu ikusi dut.

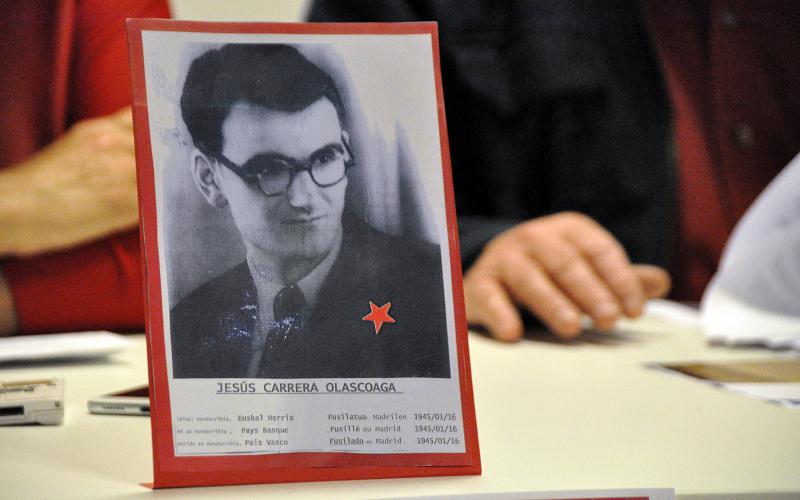

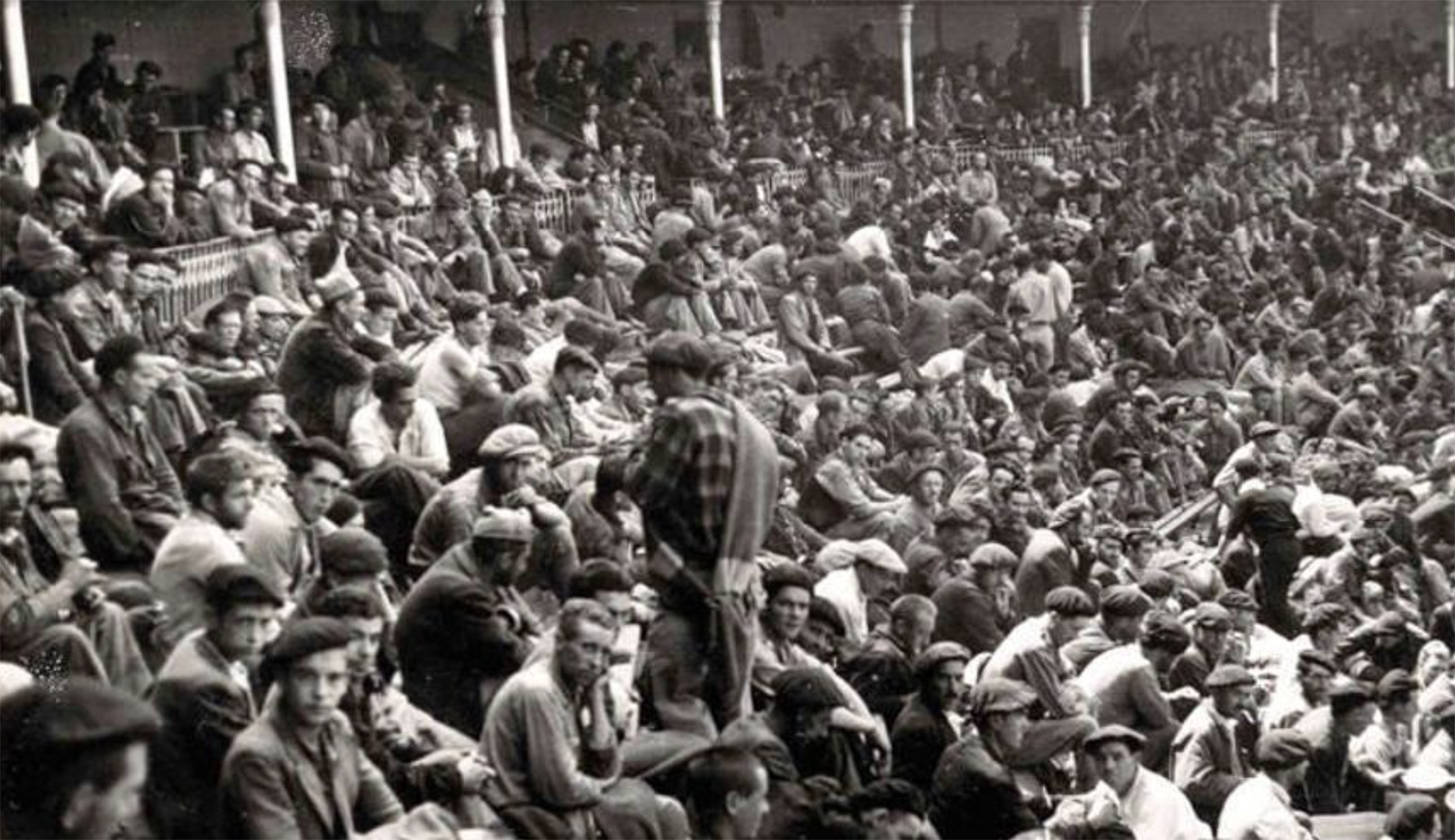

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]