At Ataolazti there's someone who remembers Oriol Solé

- Oriol Solé Sugranyes, one of the 29 prisoners who fled Segovia prison in 1976, has been arrested. He was killed by the Civil Guard at the high of Ataolazti (Bizkaia). The documentary The Segovia Big Band recalls those events on the occasion of the life and death of the Catalan militant.

The episode of the 29 prisoners who fled Segovia prison on 5 April 1976 is well known in the Basque Country. For some, Franco had just died because it was news that shook the streets; for others, a year later, an amnesty would arrive, because of the impulse to get the law; or because of watching the film The Escape of Segovia shot by Imanol Uribe, perhaps, for the youngest.

Although he has not raised controversy, the documentary The Segovia Big Band, which comes from Catalonia, has reduced dust to the escape of Segovia, one of the key figures in the fight against Franco.

29 prisoners crossed the bars of Segovia. Of these, 25 were members of the political-military ETA and the other militants of the Iberian Liberation Movement (MIL) anarchist and the Revolutionary Antiphsta and Patriotic Front (FRAP).

Although only four managed to reach the French State after fleeing jail due to tunnel drilling, one of them stopped on the road and died of a shot by the civilian guards.

The fugitive was Oriol Solé Sugranyes, a Catalan MILA militant, who died on the night of 5 to 6 April. His murder has been a reason to remember those days, as he is the main protagonist of the documentary.

The Segovia Big Band, interviews with the protagonists

Gemma Serrahima, niece of Oriol Solé, has completed the documentary, 38 years after the flight of Segovia, with the videocreator Joan Rossell: The Segovia Big Band is the name of the tour that keeps the group with its protagonists.

The former ETA member interviewed 14 people who participated in the flight from Segovia, including 40 family members. The issue has offered young Catalan videocreators an excuse to analyze the current context and the beginnings of the armed band.

The documentary makes the voices of those who have remained silent for years heard, and the protagonists have created their own story. “Although it was important that Oriol was my uncle to make a first contact and encourage the interviewees to talk, the interest has its own history,” Serrahima stressed.

What Serrahima and Rosell offer us is a simple job. “We were very clear that we didn’t want to make a macro documentary, all the work we’ve done is done by the two,” says Serrahima. “That intimate climate is the key to our documentary,” Rossell stressed. It's the pair's first audiovisual work.

The authors of the documentary have wished to give importance to the current context and the reasons why it has been incorporated into the organization. “To tell the anecdotal parts, there’s a movie!” says Rosell.

Five years after the leak, the event was taken to the big screen by Imanol Uribe. The cooperation of the participants in the flight was essential to take care of all the details and to be as faithful as possible to reality. Some also worked as actors.

Another way to get to know anecdotes and curiosities, as Ángel Amigo, one of the fugitives, wrote the book Operation Pontxo, the script of the film, published by the editorial Hordago in 1978.

The first street, the second street

Months before the escape of Segovia in 1975, several prisoners tried to escape the same prison, but it was not a success. Mikel Lejartza, a policeman infiltrated in the organization unknown as El Lobo, informed the armed forces about the intent of the eta prisoners.

The second attempt did not fail. Although they knew that the amnesty was going to come, the prisoners decided to go ahead with the flight, so that the “awareness” of the popular movements was “a stimulus”: “Franco was dead and in the Spanish State there would be no democracy if the prisons were not emptied. The purpose of the flight was for amnesty to arrive as soon as possible.” These are the words of Iñaki Garmendia, one of those who ran away yesterday evening.

Jon Ibargutxi was also there. In his words, the operation was an internal success: “Imagine, we left at 2:00 p.m. and until 6:00 p.m. they didn’t realize 29 prisoners were missing.”

They entered the tunnel and made a route of about 800 meters through the Segovia sewer, until joining those of the outside command. They arrived in the truck to Burguete, where they were going to meet the mugalari, but, as you know, in the agreed place there was no mugalari that night.

Black fog, green in the forest and Sorogain without borders

“There were two positions: The first is to stay in the truck and ask for a new appointment, and the second is to try to cross the border on our own. We took the vote. My vote at that time? To the mountain!”, says Garmendia, recalling the discussion of the truck.

Look at Amilibia, member of the outside command, remember what happened that night: “I said I didn’t go out. But at the time they were all full of euphoria, because they knew we were in Navarra. I was a young man, I couldn’t face them, I thought I was going to throw a barbarity.”

“The civil guards didn’t see us, because of the fog, but they listened to us from afar. Then I saw a pit and heard: ‘Stop, who lives?’ Pra-pa-pa! Mikel Laskurain has interpreted with his arms the movement of the rifle as it backwards into memory.

As the night progressed, the fugitives, divided into small groups, drifted down the Sorogain Forest. Five friends managed to hide in a big house. They were there three weeks, they moved to the French State and then they were deported to the island of Yeu.

The remainder were arrested by police officers on the night of 5 to 6 April. “Seeing that we had no chance to escape, we decided to go to the town and show up there. If we were shot to death, at least to be in front of people,” says Bixente Serrano Izko.

With the 1977 amnesty law, the twenty-five were released. Oriol Solé, for his part, did not reach the people, but was killed in the same forest.

“After the flight, when they stopped me, they screamed from the windows of the Pamplona prison ‘They killed Pons’ and I answered ‘No, Pons is me, here I am’. Then I realized they were talking about Oriol, who had killed him,” says Josep Lluís Pons Llobet, a party colleague and friend of Solé.

Oriol Solé Sugranyes, creator of MILA

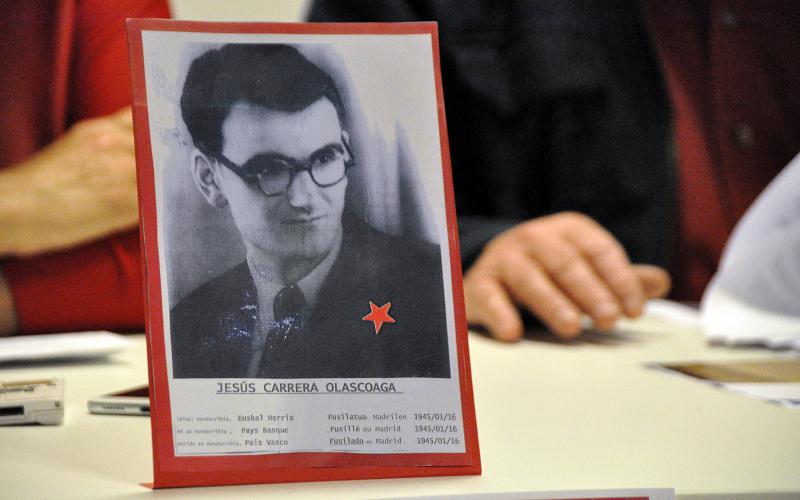

Oriol Solé Sugranyes, founder of the Iberian Liberation Movement (MIL) in January 1971, along with Jean Claude Torres and Jean Marc Rouillan, founder of the Action Directe group, among others.

“I met Oriol at the support meetings of the Burgos process and a head of ETA VI told us that a front had to be opened in Barcelona. We began to think about how to carry out the armed struggle in Barcelona, in relation to what was happening in Euskal Herria. So MIL was born,” Rouillan explained in an interview in Argia.

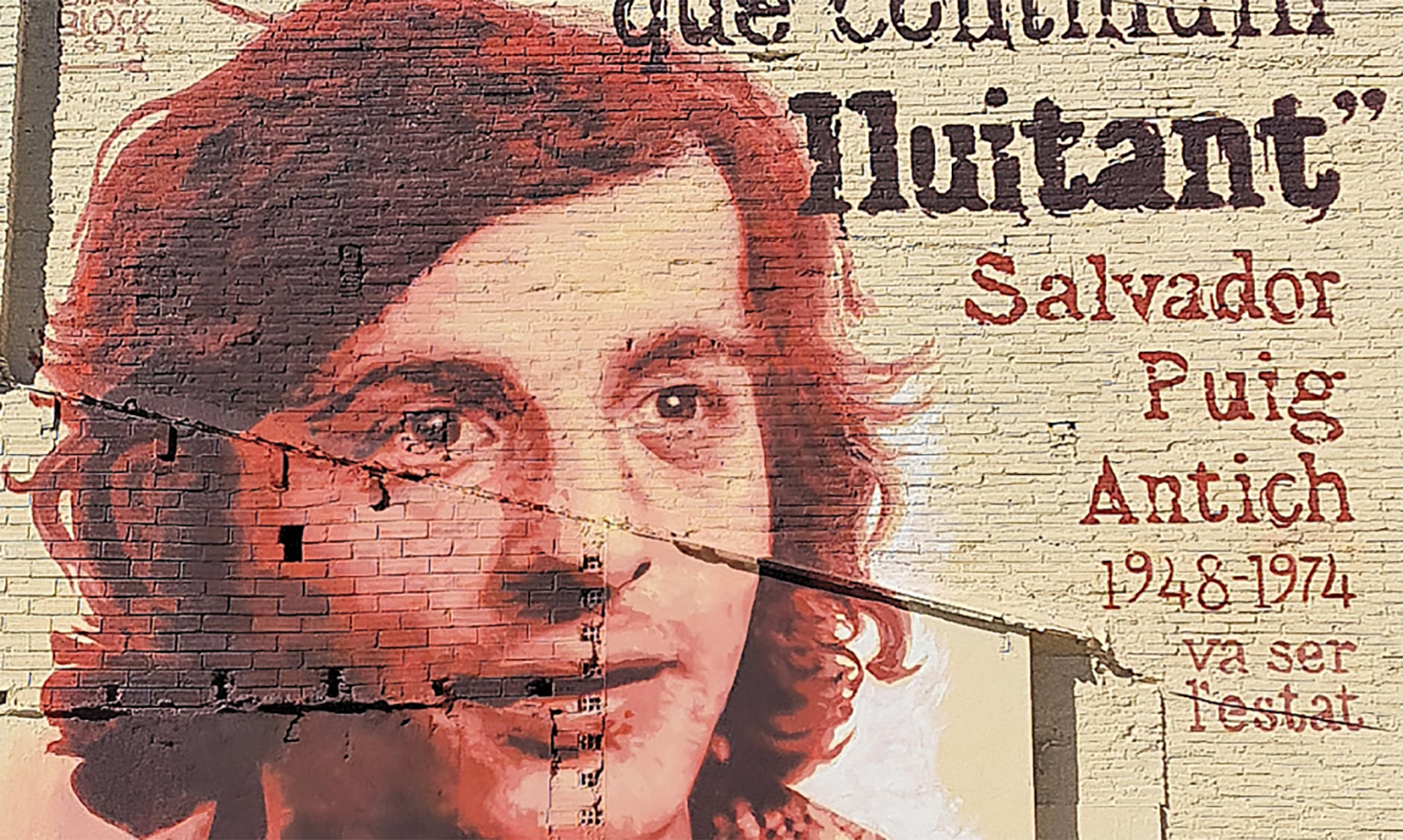

Santiago Soler Amigó, José Luis Pons Llobet and Salvador Puig Antich, among others, were friends of the struggle. Puig Antich has just been news, as journalist Jordi Panyella presented Salvador Puig Antich in January: In his book Cas Overt reveals the irregularities and new evidence of the murder of the young man, stating that there were two cases: the officer and the one that was removed.

Solé was arrested in 1973 and two years later he entered Segovia prison with his colleague Pons.

“It touched me to spy on Oriol in jail. He came from another jail, where he frequented common prisoners, so we had to know if he was trustworthy. I had to get distracted so I didn't realize what we were doing. So I found out I was an anarchist who was walking with ordinary prisoners. Oriol was a good guy!” says Friend. “The day before we realized the leak and offered him the opportunity to participate. ‘That’s how things are done,’ he said, very surprised,’ recalls Serrano Izko.

The limit is easily seen from the monolith, now

On 5 April this year it was a special day for colleagues who participated in the flight. They all met in Burguete (Navarra) and paid tribute to him in a monolith located in the place where Solé was murdered in Ataolazti.

The Solé Sugranyes family, their friends and 22 of the 29 women who were on the spot were there. Oriol's mother, Xita Sugranyes Franch, 94, has also become a mother of Oriol.La mist covering the ground

and making it squeak like that night they had jumped out of the truck. Without a career, the attendees resumed the road between Burguete and Ataolazti.

The boundary is now easily seen from the monolith, as the two stones that form the monument show the way to Urepel. One of the stones is Solé, his hometown, and the second is Ataolazti.

Look at Amilibia, in the place where Solé was killed: “We are of the generation to whom it was incumbent to fight fascism. Yes, we made changes, but this new political relationship, which has been called ‘democracy’, has silenced those who think ‘different’, and has guaranteed the national unity that sets the powerful in power. But your memory, Oriol, helps us maintain our beliefs so that we can continue to participate peacefully and actively in the construction of a free, solidary and sovereign people.”

Serrano Izko stressed the importance of memory: “History has marked us, it has marked us the present or not, and now we are trying to write the history of the future. But memory is a mental exercise we do with the experiences of the past.”

We will then do a mental exercise so that the flight of Segovia does not become the title of an obsolete film without special effects, and when we read on the plate of the monolithic of Ataolazti the name of Oriol Solé Sugranyes, let us know what he was and why he lived there.

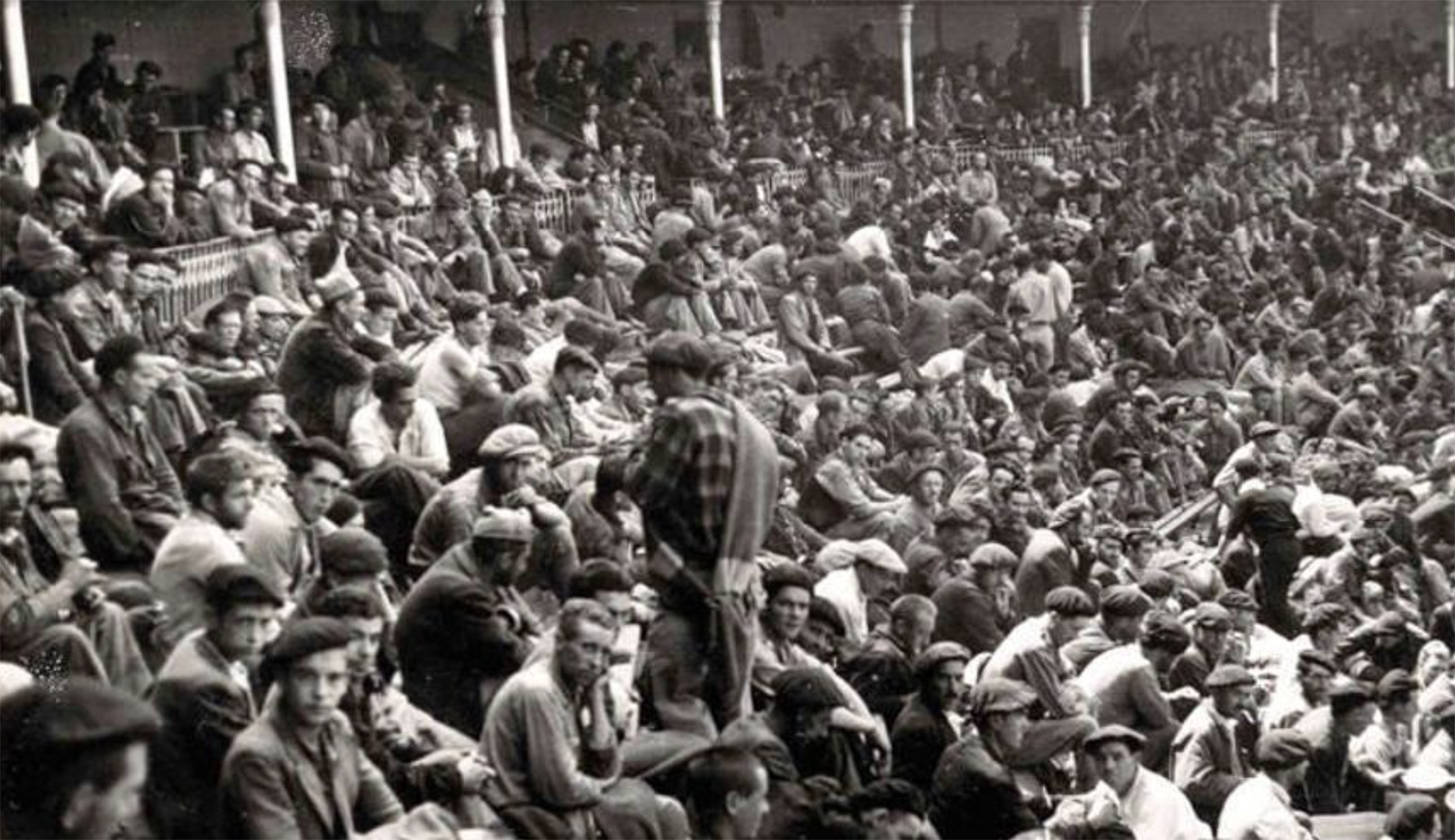

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]