"Weapons can be handed over to anyone except Madrid and Paris."

- “He was one of the founders of ETA in 1959. Only three of them survive. Clandestine, torture, jail, death, ETA problems... He is 82 years old and had to write before he died this book: To the truth. There will be something to say.

You say you should have written the book before you died. You have a lot of things, especially ETA. Some people won't like it very much.

Probably not. I was two or three months pretty bad, thinking about whether or not I should do this job, and I decided yes. My questions were as follows: I had to tell everything I'd seen, regardless, yes or no? Yes. And the next question: Who does he write for? For the Basque Country and especially for young people. The Basque citizen is therefore entitled to know what has happened, whether what has happened has been hard, nice or sad. Sweet and unpleasant events appear in the book. These last ones I have not done; I only write them, I expose them.

ETA is still alive. Can those words influence anyone?

I don't think so. A distinction should be made between ETA and ETA militants, and ETA should be targeted. In ETA they have been militants of all kinds, in very different ways, and whoever reads the book will see that in most cases I speak well of my colleagues. But in some cases it doesn't, and I've told you. Then it will be our people who judge. The Spaniards say, “Let each stick hold its sail.”

It says that the name ETA was created in 1959 by Txillardegi Enparantza Jose Luis Alvarez, but that the year of foundation is, in fact, that of the creation of Ekin in 1952, which in 1959 was nothing but a change of name. Could you believe I was going to have that journey?

No, by no means. In 1952, at the University of Deusto, Joxe Manu Agirre, Gurutze Ansola and I had as a professor Aita Urrutia, who brought us together. So I started sharing with them my concerns about Euskal Herria, and then we got closer to more people and created Ekin. Soon after the break with the PNV, we founded ETA in 1959: Jose Maria Benito del Valle, Joxe Manu Agirre, Mikel Barandiaran, Txillardegi, Rafael Albisu, Iñaki Larramendi eta nik.

Did they really believe that they could achieve independence for the Basque Country?

We were able to see whether our people are moving forward in the struggle and whether this rude action of repression of action is constantly intensifying. Our major leitmotiv was: “We have to do something” to recover the Basque identity, the character… everything that was beating Spaniards. But for that we had to regain independence. The class struggle came later, at the hands of the national perspective; first we had to liberate the people and then we had to commit ourselves to social freedom.

You were the first head of ETA.

We first chose another partner as a “boss,” a friend and a beautiful friend, but he said he was not able to do it. After a lot of work with the potential candidates, they put it to me, for six months. To make the choice we took into account the situation of each one, the family… and, although I was married and three children, I thought someone had to be and I said yes. I went back to the South, formed and organized groups, it was a very intense time; as a security measure, for example, never two nights in a row at the same place.

Because of the raids, through the internal contradictions and your organization, in the book you often mention that you were very worried, but ETA ran over and over again.

The contradiction of the national and social problem was always there. Krutwig [Federico] compared the contradiction with a missile of two Estaicos, the lower part was independence and the higher the class struggle. If the first floor doesn't work properly, it doesn't force the second floor and the missile can't get up. The class struggle was sometimes speeded up, but in the end independence was always in the foreground.

In the book you mention that from Franco, little by little, ETA is losing the support of the people. Where did you see the signs?

It seems that the question is simple and has a simple answer, but it doesn't. Armed struggle was an instrument that we put in the hands of the people to achieve independence. Furthermore, we had established that our internal functioning and our way of acting with our environment should be democratic. I append in the book the two critical letters I sent to ETA’s management in the early and mid-1980s, when I was merely a militant of the organization. Probably without realizing it, but I think ETA's leadership was moving away from the village and that wasn't right. I didn't even see how we were playing with our Iparralde Abertzal brothers [talking about the problems between ETA and IK].

When I started to criticize ETA, it was first always with words and within us. But he didn't care. One day, in 1986, Txomin [Iturbe] came up to me and asked me to look for a house, to come up with three executives to talk to me. They were Juanjo Aranburu and Zekorra [Josu Urrutikoetxea]. Everyone threw their own and we listened with respect, but for a moment, while talking about foreign policy, I said that we could not trust empires like the Soviet Union and China. When I heard it, the calf interrupted me suddenly and in a brutal way, completely scared, and told me I couldn't. The other two were amazed, and they told him that I could not take my word and shut it down. We were talking all day and I was told that we would meet next time. Then I had the opportunity to be with the management representatives twice, one with Txomin and the next with Zekorra.

He says that the direction was ever further away from the people. What did I feel like?

In some respects. For example, at a time when there were major demonstrations or initiatives, ETA committed an attack on the day before and frustrated those initiatives. Later, in the 1990s, the attacks on PP voters began, [Gregorio] against Ordóñez, [Michelangelo] against Blanco… It seemed that there was a mole in ETA or in the direction of ETA to frustrate the good initiatives that the people were taking forward. I had thought about it, Campanilla too, and he had written it. When this happened, in the next elections the Basque parties were always declining and enemy parties were always rising, especially pp. We were doing something wrong.

I made my written criticism of the institution, they appear as annexes in the book, but they did not answer me. The only answer came in the early 1990s. Campanilla came to tell me that they had given me a letter. It was a general letter, saying that I was wrong, that the other colleagues had taken too badly from so many things and things that I did, but without a concrete answer.

The 1980s was very hard for you, both because of the repression and because of the problems you had inside ETA.

The enemies of Madrid and Paris are very strong, much more so than ETA, and their blows are very hard, but they are much easier to accept. You go to jail, you go abroad, you go to Belgium, you go to Mexico -- and that makes us weaker.

In 1988 he was re-incarcerated in Fresnes prison in Paris, where he lived one of the hardest moments of his life. You lived the death of your 19-month-old daughter Iraia and the relationships you had with other ethnic groups were also bad. You thought of committing suicide.

Yes, it was a tough time, especially because of my bad relationship with Zekorra. At first I was in the cell with Txikierdi [Juan Lorenzo Lasa] and another one from Goizueta who we called Harakina. Shortly afterwards, Miguel Strogoff was transferred to the dungeon, where he remained in prison and instead took Ternera to the cell. We had no good relationship and the Butcher rushed to realize it, although we had not talked about it in the dungeon. The butcher immediately joined the Calf and made my life very difficult. For example, everyday tasks were always distributed, food was made, cell or toilet cleaned, etc. All of a sudden, I realized that some jobs, dirtier than others, like flushing the toilet, I had to have done more than others. And I told them that that wasn't right, and the Calf responded that the decisions were made there democratically. Of course, it was always against two, always doing what they wanted. Every day I was about to burst into that bad environment, and also in that environment I had lost my little boy…

The calf had its grupit, and some of them, through the windows, screamed out loud, so I could hear it well: "Hey, the fucking son when we're going to clean the lining?" (Hear, when are we going to clean that whore?)” In the courtyard they also insulted, in Spanish, so that the brothers of Iparralde did not notice. Again, it rained and we went to the gym inside; I started doing yogging and Zekorra as well, but she in the opposite direction, and when we came across, she stuck with me brutally, so no one realized it. He tried it on the next lap, but I avoided the blow, and on the third I jumped on top. I kept running and he knelt down, and as he went back before him he said to me, “You’ll lean or you’ll have to burst it.”

I was really bad, and I started thinking about how to commit suicide. And as I was doing this, one day the guardian came and told me they were changing my cell. It was going from hell to purgatory. And after three or four months of being alone in the cell, I was taken to another department. There were, among others, Santi Potros [Santi Arrospide] and Azkoitia [José Luis Arrieta], good and clean people, and went from the purgatory of the biggest to the sky. I wrote to the ETA management denouncing this whole situation, but I never received a reply.

He says in the book that ETA subsidized the prisoners and that you were the only one who did not receive your money at Fresnes.

Yes, and I asked the institution for that and Zekorra, and he told me that the organization was conducting an investigation to see if I had any dealings with the police with the latest detention accounts [1988]. Well, being already in that prison heaven, Santi Potros came to tell me once that he would receive compensation, which had already been surveyed, that nothing bad had come out and that the matter was completely resolved. “If I’ve already solved myself – I answered him – and I’ve committed suicide, how do you fix that?”

He started in the 1960s and was last incarcerated in 2006. Among them are clandestine, torture, deaths, jail, normal life... and also two women and eleven children. How do you get all of this at once?

I don't know. More than once I've wondered about this and I don't know. It's hard to answer. Many times I've thought: “Everything has been too much, but I’m alive.”

You say that there has been no end worthy of ETA. Is it still possible?

If there are some conditions, yes. The issue of arms, for example: arms can be handed over to anyone, for example to an international commission, except to Madrid or Paris. It's a matter of dignity. As for the prisoners, they have come to the streets in all the wars and conflicts that have taken place in peace processes and here too, although patience will be needed, they will come out.

There is much talk in the book about suffering, especially the suffering suffered as a result of repression. But ETA too has caused great suffering. Being in a peace process, what would you say to the families of those killed by ETA?

This question is very difficult for me, because I can't lie. A war, a conflict broke out, and as a result many people have suffered. I do not know what the exit is, but I have said many times: “Who entered the house of whom? The Spaniards in our country or us in yours?” And the same is true of the French.

Many people on the Abertzale left tell him that he has to do self-criticism. He says he has done it, let others do it. Should you do more? How far?

First, it has to make self-criticism of the enemy who has entered our house, and then we will also do our own. Two self-criticisms must be made, one against the enemy and the other against Basque citizenship.

In ETA’s letter in the annexes, ETA accuses him of personalism.

Yes, on more than one occasion they have dropped that, but they have never explained to me what they were based on. Once one asked me if I would be lehendakari. “If the village chooses, it would be ready,” I answered simply. I've done what has touched me, like the one who elected me head, or many others. I have always carried what I thought and what I did, with all the consequences. I never had trouble asking for forgiveness, if I wasn't right about anything. With the people I've worked with, in the underground or otherwise, and who have known me well, I've never had problems and we've managed well.

Have you ever thought it would be better if you hadn't created ETA?

[Silence] No. But I realized that the ETA that we created was dwindling in the last few decades.

What would you say to ETA today?

I know that it is difficult to measure, but that it fulfils the will of our people.

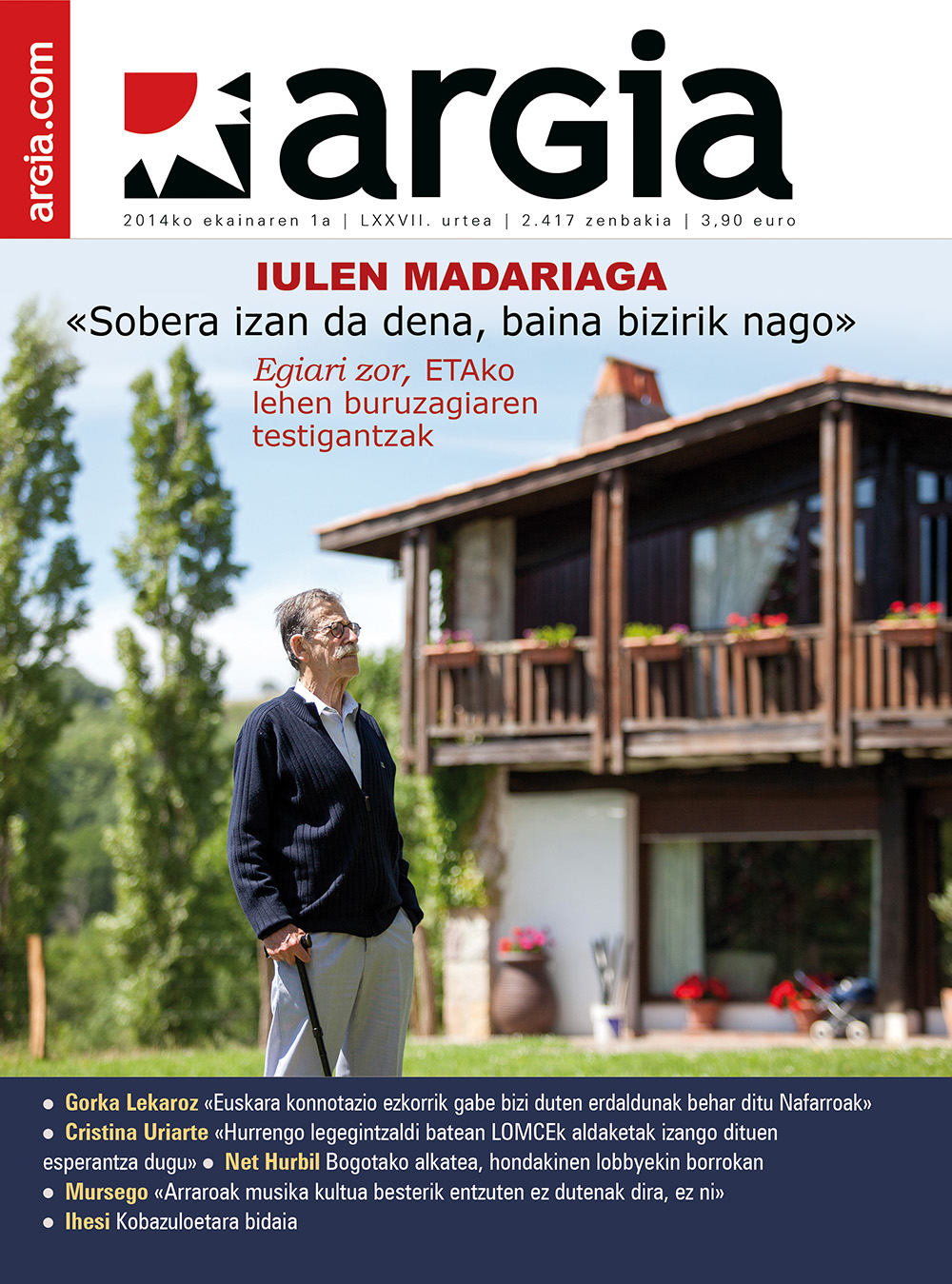

Iulen Madariaga. 1932an jaio zen Bilbon. Madariagatarren aldetik, Bilboko familia abertzale ospetsukoa. Gerra umea, familiarekin Txilera erbesteratua.1959an ETA sortu zuen taldekoa eta erakunde horretako lehen buruzagia. Espetxea, atzerria, tortura... hamarkadetako kontua bere bizitzan. Bi emazte eta hamaika seme-alaba izan ditu eta horietako biren heriotza ere ikusi du. Aralar alderdiaren sortzaileetakoa izan zen. 2012an iktus batek jo zuen eta, makulu beharrean bada ere, oro har, sasoiz ageri da. Egiari zor liburua (Erein) idatzi du.

Fresneseko espetxea, 1988ko irailaren 23. “Iraia alaba gazteenaren heriotzaren berria iritsi zitzaidan burdin barra artetik. Hemeretzi hilabete zituen eta etxeko igerilekuan itorik aurkitu zuten”. Ez zioten hiletetan egoten utzi, ezta familiarekin ere. Alabarekin bai: “Iraiaren hilotzaren aurrean egon nintzen luzaz, halako burbuila bat osatuz gure inguruan. Sakonki hunkituta nintzen, eta gure bazterretan iragaiten ari zen guztiak ez zuen izenik”. (Egiari zor).