For so much and more

In early November 1936, five Mondragon women were shot by Francoist troops. Florence Olazagoitia was 40 years old when she was killed. She was the mother of three children, who died five months pregnant and was arrested by the police. But these cases were an "exception"; the majority of those arrested, imprisoned and shot in the war were men. Arrasate 1936: The people who have testified in the documentary on women, war and repression are hidden in the last row of the protagonists of the war. They're on the losing side and they're also women.

During the presentation of the documentary, Julia Monge, of the association Intxorta 1937, stated that gathering these testimonies has not been an easy task, since some have left behind and those who have spoken, on many occasions, do not give them the importance that their experiences deserve. Maybe that's why testimonies are humble, worthy. And the authors of the documentary have been able to maintain that tone. In the absence of a real picture of what has happened, the City Hall has resorted to dramatizations. In addition to adequately mitigating the representations, they have avoided an unfounded drama. The protagonists do not fall into victimisation, even if they are victims. Going out alive doesn't mean they haven't been victims. The women of the gunmen, sisters, daughters, had to go and search for their bodies to Ondarreta prison, or cut their hair to their hairs and had to suffer the humiliation that this entails.

The other day I read on a blog that cutting hair to women is usually a matter for fascists, but not exclusively. Many French women who related to the Nazis at the end of World War II were also cut off as public humiliation. When I saw the documentary, I remembered the comment left by a reader at the end of the blog post: “It’s not so much, the hair grows.” The simplism of the commentary is offensive and, as a metaphor, totally wrong. Hair grows spontaneously, but for those mondragonese women after the war, things were nothing but rich. Some had to be exiled, others had to receive the whole family, and they had to work hard, at least when they could work, because often those who were looking for work received this answer: “There’s no work for the losers.”

The merit of these women is not only to have suffered the consequences of war, but the ability to move forward in the long post-war period. But in his words there is neither heroism nor rage, as if they had reconciled those who had lived in war. Those who refused to speak in the documentary prefer not to remember each other. Some of the participants have highlighted the others, taking self-importance. But at the end of the documentary, a witness responds to years of contempt, contempt, silence, serious, staring directly at the camera. “For so much it wouldn’t be… For so much not, more.”

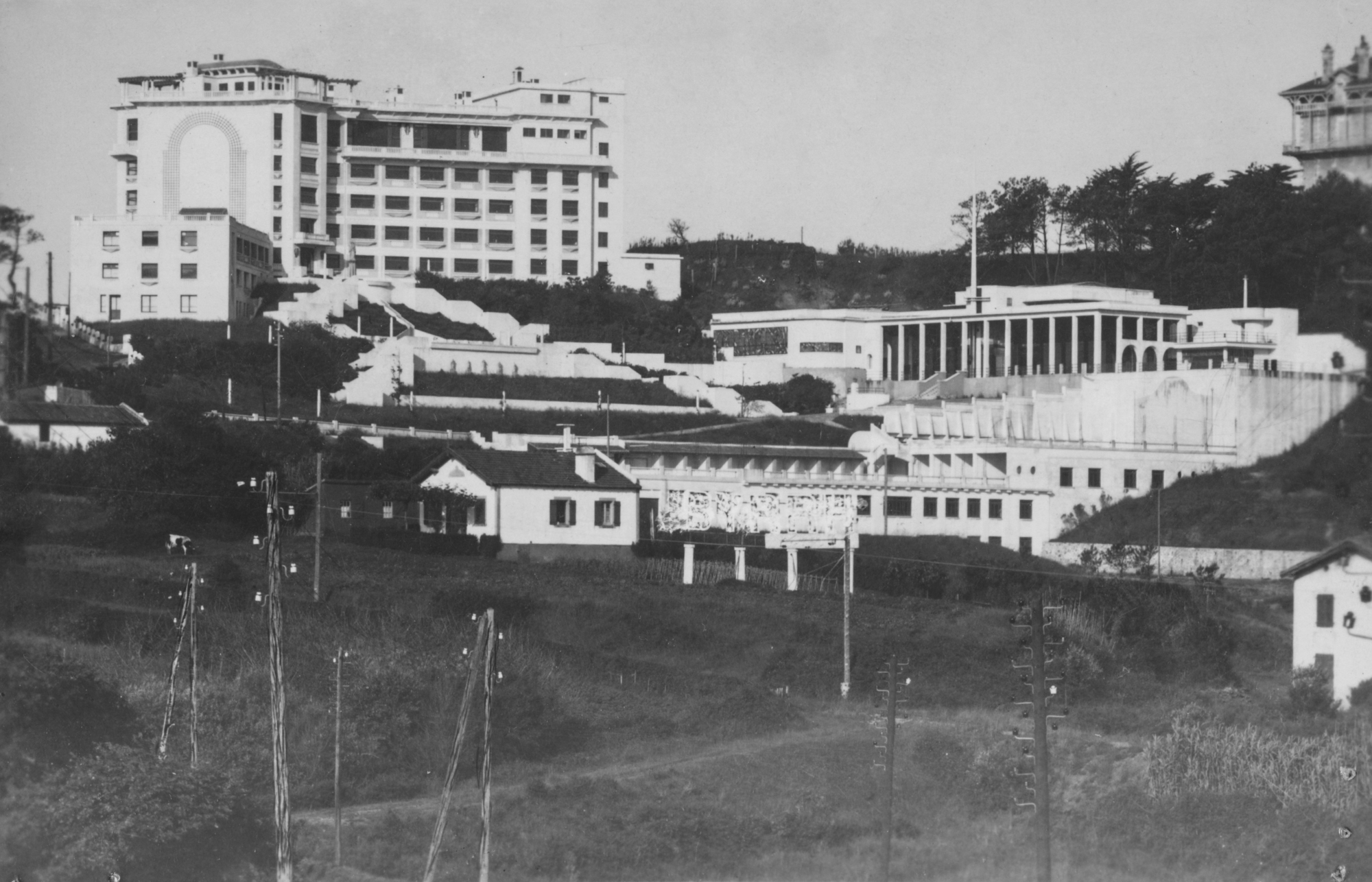

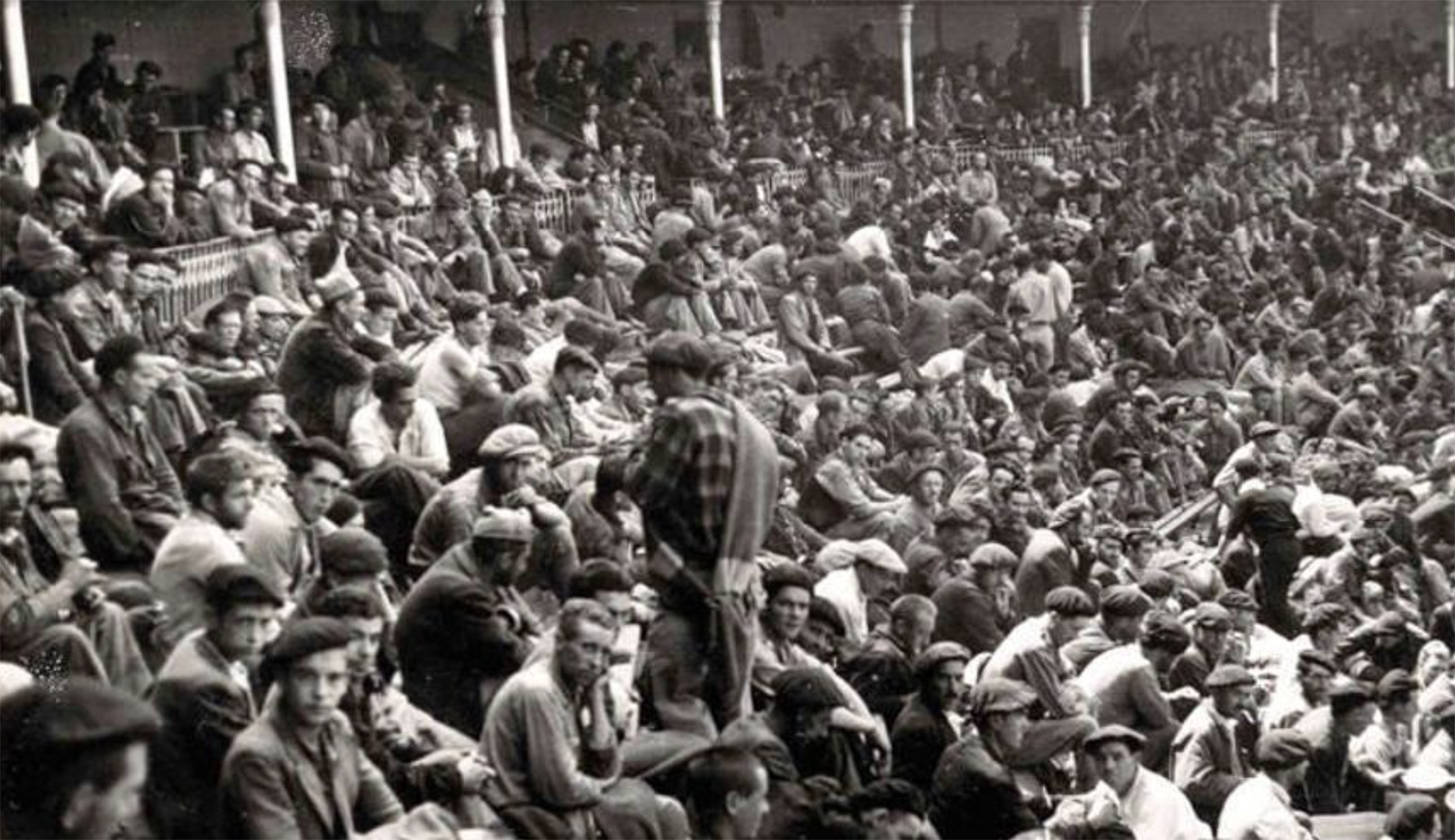

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

Segundo Hernandez preso anarkistaren senide Lander Garciak hunkituta hitz egin du, Ezkabatik ihes egindako gasteiztarraren gorpuzkinak jasotzerako orduan. Nafarroako Gobernuak egindako urratsa eskertuta, hamarkada luzetan pairatutako isiltasuna salatu du ekitaldian.