"We have a hard time seeing how far we are culturally colonized."

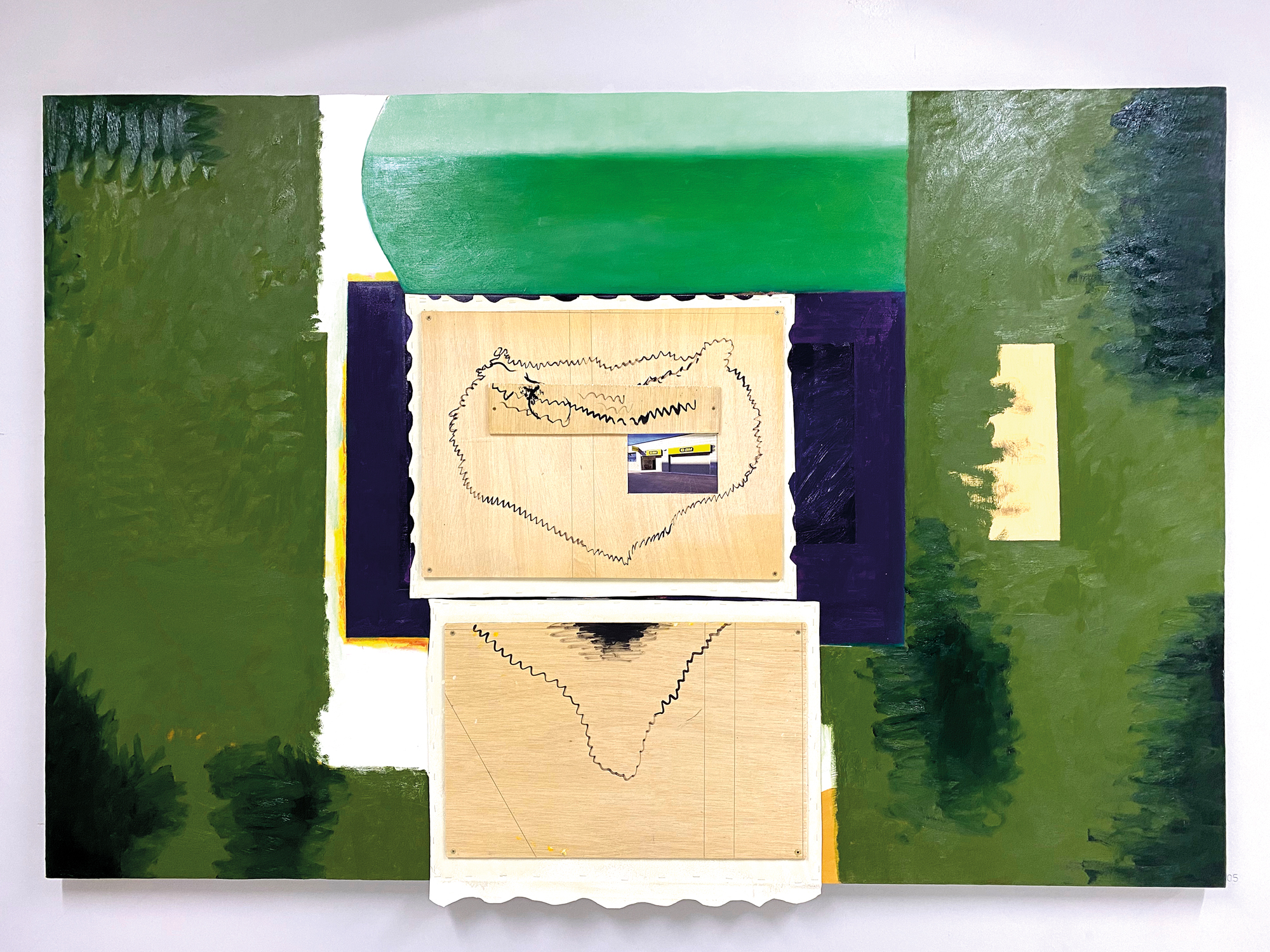

- Faced with the giant and hard paintings of Xabier Morras, we are all small.

What do you do now?

I am preparing an ambitious exhibition with my work over the last ten years. I do a few exhibits. If you ask me for work or drawings for an exhibition, for example, for Nafarroa Oinez, I do put them in a dispersed way, but a great exhibition, one of those that gathers the core of your work in recent years, the last one I did 12 years ago. This will be installed in the City of Pamplona in October or November. Last year I had to have done it, but I had cancer surgery, and I had to cancel. In these paintings you'll see the themes that I've worked my whole life.

The terrible buildings of the big cities and the scenes here?

Yes. That is precisely what that ugly Gothic word means, which is now so fashionable. Local and global. We all have superimposed worlds: the first near and then the one that we learn to shape our own universe. I've made a lot of trips and I've lived many years out. I don't know if that's good or bad. So I met the urban scenographies of big cities: London, Chicago, New York… I’ve always had a great interest in the architecture of the giant skyscrapers and the time they were created. I'm fascinated by those early 19th and 20th century buildings. In those years, society still believed in the future. They believed in unlimited progress. Great entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs, architects, engineers and together with them the best sculptors, ceramists, stained glass, craftsmen… All united to build buildings for the future. They were palaces or cathedrals of the 20th century. Fantastic buildings. I want to pay tribute to those dreamers who carried out these projects. In addition to this sense of admiration, I also want to show how painful it is for me to knock down many of those buildings or to see their current poor state. On another scale, the same thing happens here. Since I was a young man, I have been very interested in the houses of the villages and in ten years I made my doctoral thesis about them. My father was from Lakar and my mother from Zabaldika, from Steribar. I am impressed by the skyscrapers, but I find the houses of the people the same. Lakar's house was like Noah's. All filled with animals, lots of wheat in one place, in another they made straw or nuts and apples, oil and wine… It was a wonderful world of new smells and touches for a street kid like me. I don't know if I was lucky or miserable in knowing all that, because then that world collapsed and disappeared forever.

It was hard times and thousands of men and women had left and the people had run out of youth. Those houses, which I wanted deeply, began to collapse. Bonfires and gossip were extinguished and I know I will not live again. The emptiness left in you when that world disappears, nothing can heal you. People left those wonderful homes to settle in the disgusting neighborhoods of cities. I don't know what would happen to these people's heads and hearts by leaving their homes, fields, roads, orchards, animals -- their nights, cold and hot, but I think they suffered a lot. There are peoples who have been destroyed by eviction, but there is another form of destruction: excessive and misguided development. Small towns quickly industrialized, building abominable neighborhoods that devoured old houses.

That hurts me. And the same is true of skyscrapers, railway stations and old factories. They're not here, because they're very small, but they're also with the gigantic fabrics or the big iron factories in England. The first time I saw them, when I was 22, I discovered something mysterious. You know what's in a church, but you can't get into a factory -- gigantic dark brick buildings, smoky fireplaces, huge windows -- it was really exciting. I wanted to reflect these feelings in many paintings.

In addition to the paintings for this exhibition, in recent years you have turned to another large painting: Battle of Amaiur. How is it going?

It's a very special job, which I'm doing with passion. It is my personal tribute to the defenders of Amaiur. It's a custom car that I've made myself. About ten years ago, when the fifth centenary of the conquest of Navarra was approaching, I thought I wanted to do something, but I didn't know what. I needed something historic for many reasons. On the one hand, it's hard for us to see how far we're culturally colonized. We are totally colonized by external cultures. When I was a child, I saw the works of art that reflected the very excited historical events in Spain, but then I started thinking about why Isabel Católica asked me the keys of Granada or Numancia or Anibal and I don't know what. We don't realize that they're violating us intellectually and sentimentally. These great works of art are great, certainly terrible, and you make yourself unaware of the story they tell. If no one explains to you that this was a kingdom, that the Basques have our own history, or that the outings are, you cannot know. I started looking for all of that when I was young. Maybe, traveling a lot, I started to see what my heart was touching and what wasn't. After all, you discover your own reality when you compare it to others.

I felt like a painter that I had to make my contribution and I chose the battle of Amaiur. It was not the only or the most important, but young people were fortified there with great energy, waiting for a formidable army. They weren't jerks, as some historians say. They knew very well why they were there. Amaiur. OK, but what? I was three or four years pondering until I decided which scene I wanted to reflect. The same battle is not, because it is not clear who it is, the moment after the defeat was humiliating… In the end I decided to try to catch the moment when our soldiers saw the enemy in sight. They look far away, very worried. Once this was decided, it occurred to me to put familiar faces, names and surnames to our defenders, to pay tribute to people who have been very important in my life: Jimeno Jurio, Pablo Antoñana, Jorge Oteiza… and many other colleagues who have died. It's very difficult to show all these emotions on the face without fright. Teaching mothers to cry and cry because they have to kill their children is not our style. We are Navarros. It is clear to me that this work must be legible and at the same time very dignified and of artistic quality. I've been with this for eleven years, and I still need three or four more.

In 1972 he participated in the prestigious artistic meetings held in Pamplona. In addition, you had to remove one of your jobs. Why were they so important?

They were encounters driven by the Huarte Industrial family. They were very fond of art and apparently wanted to give something to Navarra. These days were set in motion every two years. The director was led by the composer Luis de Pablo and the artist José Luis Alexanco. They managed to merge what had never been reconciled here before: high contemporary culture and popular culture. For example, New Yorker John Cage and a ball game by hand. I think that was the most important thing. And it hasn't been done again. It was very interesting, but at the same time you can say that they came up with the idea of a cultural colonizer. They did not foresee a place of their own for Basque art. At the last moment we were put in a corner of the Museum of Navarra. I was very angry with the whole atmosphere of violence of the time. I've never seen anyone throw at the slopes in war or after war, but I've always heard such terrible stories. That is why it occurred to me to put the head of Jesus Christ, with his mouth covered, on a bleeding canvas, and on both sides two national policemen dressed in gala, as if they were going to attend a procession. I put all of that in a kind of black cockpit. The size of the work was impressive and the result was impressive. The organizers asked me not to withdraw and I did so because I wanted the meeting to go ahead. On the first day, another Belarusian painter was also censored by what Ibarrola and other members of the Communist Party said they wanted to give a standardisation appearance at these meetings, but it was not true and it was also funded by some capitalists, etc. The meetings were held in one way or another and many surprising works could be seen, but they were not carried out again. There was everything left.

Recently the Culture of Scarcity group denounced that our authorities want submissive artists and an art that does not bother. What are the relationships between art and power like?

Great art has always gone hand in hand with power. Customers have always been rich and powerful, and artists are very submissive with great orders. However, this does not mean that the results were bad, but that tremendous work has been done. Art can be good and not disturb power, or on the contrary, or neither. The only thing that is clear is that nowhere do they know what to do with artists. The state of the artist is that of mere precariousness everywhere: In Germany, France, Great Britain, Finland… A few manage to live from their works of art and most have to dedicate themselves to many other tasks. Receiving aid from the institutions is very difficult. I have been painting for over 50 years and so far the City Hall has bought me a single painting, the UPNA a drawing, the Provincial Council of Navarra a small painting, and it is now. They say that young people don't have help, but older people don't. I have been able to move forward because I have worked on other jobs. It is difficult to receive something from the administration, as those responsible for the dynamization and dynamization of cultural structures usually do not have enough capacity and creativity. You should know that you can do things even without money.

Why do you paint?

Especially to know myself. It's a form of hospitalization. Each of us is a chasm. It's me who knows and I don't know. Arreto a lot of painting. I need to paint something that gives me vertigo. Intellectual and physical vertigo, something stimulating and that I fear at the same time. Fear of not knowing what is going to come out of there or whether it is going to have artistic quality. Devoting a great deal of time to the mental representation of the work or to the process of elaboration does not guarantee a satisfactory result. In all creative processes there are three phases: the first is to conceive, the second is to do and the third is to check whether it works or not. There I have many doubts and in those moments I always risk myself. For me, it's very stimulating, very stimulating. What catches me the most is creating beauty. By beauty I understand doing something that no one has done before, as I want, with my touch. I want to create BEAUTY with capital letters.

Xabier Morras Zazpe (Iruñea, 1943). Margolaria. 22 urte zituela Nafarroako Diputazioaren beka bat lortu zuen Londresera ikastera joateko. Gerora New Yorken eta Edinburgon jarraitu zuen formakuntza 70eko hamarkadan. 1971tik 1986ra Nafarroako Aurrezki Kutxako Kultur Aretoko zuzendaria izan zen. Bere lanari esker, gune hau nabarmendu zen Iruñean abangoardiako artearen zabalkundean. Zuzendari izan zen 15 urteotan mila artistak baino gehiagok beren lanak erakusteko aukera izan zuten. 1987tik irakasle izan da EHUn, Bilboko Arte Ederretako fakultatean. Oteiza Fundazioko patronatu kidea da sorreratik. Miren Aranoa Bilduko legebiltzarkidearen senarra eta hiru seme-alaba gazteren aita da. Hizlari aparta, distiratsua. Nafarroa eta Euskal Herriaren aldarrikatzaile nekaezina, kritikoa eta konprometitua. Ausarta, zalantzarik gabe, bere margolan errealista, gogor eta ikusgarriak bezalakoa.

“Beste norbaitekin bidaiatzea oso atsegina dela ulertzen dut, baina bakarrik joatearen aldekoa naiz ni. Harreman sakonena, egiazkoena errealitate horren eta zure artean, horrela sortzen da, filtrorik gabe. Benetan harritzen zaituena da zuk zerorrek aurkitzen duzuna, lehen inork esan ez dizuna”.

“Pentsamendu, sentsazio, astintzen nauten bibrazio fisiko eta mental bizkorrak izatea gustatzen zait. Bizitza arruntean dagoena niretzat ez da nahikoa. Nahi dudan arrisku hori arteak ematen dit”.

“Gauza bat da diru-laguntzarik ez jasotzea eta oso bestelakoa erakunde batek zu ahaztea. Niri gobernuak esaten badit hitzalditxo batzuk antolatzen dizkidala, erakusketa batzuk hainbat herritan barna, soilik gasolina ordainduta,ahalegina eginen nuke gustura. Baina hori ere ez dago: ez laguntzarik ezta interesik ere. Ez dago ezer egiterik”.

Lehenagotik ezagutzen nuen Xabier. Horregatik presarik gabe joan nintzen bere etxe-lantegi zoragarrira. Bere koadro erraldoi eta milaka libururen artean hartu genuen goxo-goxo kafe suabea. Katilukada bat eta beste bat, lasai ederrean. Banekien hasi aurretik berak niri eginen zidala elkarrizketa: non idatzi, zer nolako beste lanak, nori egin diodan elkarrizketarik lehenagotik, Argia zer moduz… Interes ikaragarria. Eta segituan berak bere buruari lehen galdera: “Zertan nabilen orain, adibidez?”. Grabagailua piztu eta hortik aurrera, kafeari hurrupa txikiak hartzea eta bere azalpen koloretsu eta pasioz beterikoak aditzea izan da ia ene lan guztia. (Elkarrizketa honengatik ordainduko didate eta neuk ordaindu beharko nuke?).

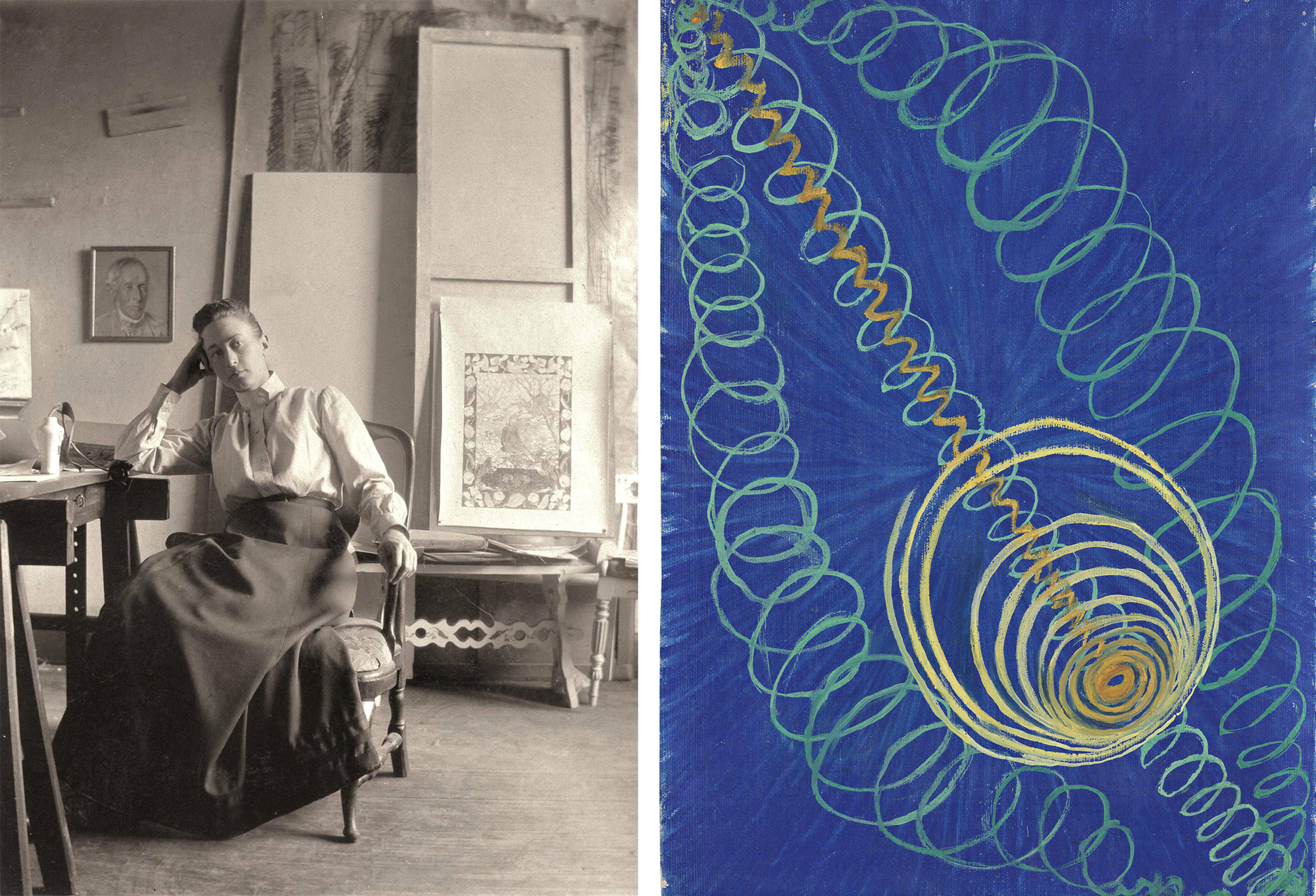

Bussum (Netherlands), 15 November 1891. Johanna Bonger (1862-1925) wrote in his journal: “For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on earth. It was a long and wonderful dream, the most beautiful one I could dream of. And then came this terrible suffering.” She wrote... [+]