The baserritars don't want to live on subsidies.

- With the creation of the European Union, a common agricultural policy began to be established, the 2nd European Congress on Sustainable Agriculture. To deal with food shortages after the World War. The problems came in the 1990s, when instead of controlling the markets that it had dominated until then, neoliberal policies began to prevail. Twenty years later, the sector has become an alternative sector of poorly distributed subsidies.

If appropriate measures are not taken, the Basque primary sector could be on the verge of disappearing. Thus began the column For another agricultural development model, written two weeks ago by Juan Mari Arrangi. It can make a claim that is too fat, but it is in line with the opinion of the agricultural and livestock unions that dominate the Basque country. According to them, the policies that come from Europe are generally to the detriment of traditional farmhouses.

The impact of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) on baserritars is a subject of ongoing debate in the sector, but more intense when implementing reforms. This year, precisely, the conditions for the period 2014-2020 are being laid down. In particular, compliance with the requirements for the granting of grants. Aid is, as we shall see, at the heart of Brussels' policy.

Two decades of progress towards neoliberalism

The reforms suffered by the CAP since 1992 have been “a tremendous failure”, according to Andoni García, of EHNE-Bizkaia. “A production model that benefits the business and the food of the population is not considered a axis. It is possible that the food supply cannot finally be secured.” García pointed out, for example, that since 2003 the income of farmers in Hego Euskal Herria has been reduced by an average of 23%. Let us see what the path has brought us to this situation.

At first, market control

In Ipar Euskal Herria, the NPB has regulated the lives of farmers in the last half century. In fact, the common agricultural policy emerged in the late 1950s in cooperation with the European Economic Community, and France was there among the main drivers of the CAP. “In post-war Europe there was a food deficit,” explains Mixel Berhokoirigoin of the ELB trade union, “only 80% of what was consumed”. The CAP is born and achieved in order to give a boost to production. In the early 1980s, Europe had a surplus of food each year. This was achieved, inter alia, by supporting the activity of local farmers. According to Berhokoirigoin, the main feature of the CAP in the first decades was market control, including fair price assurance for producers.

“The change started in 1992,” explains the OECD member, “and it was for political reasons.” Andoni García recalls that time, because by then there were also baserritarras from the South in the CAP area: “That year the first reform of the common policy took place and the CAP radically changed. Until then, the policy was based on price protection, but subsidies began to become increasingly important.”

The context of the time must be taken into account: At the beginning of the 1990s, the EU was engaged in negotiations on the new international treaties. The result was an increasing liberalisation, in which there was no policy such as the CAP, at least with the above characteristics. Market control, including the political guarantee of prices received by farmers in exchange for their products, began to weaken and has continued to weaken with every reform that was made since then.

In order to alleviate the losses suffered by farmers for this reason, Europe has set up a package of economic aid. The following data from Mixel Berhokoirigoin summarizes this evolution of the twenty years: “When the CAP was created, 80% of its budget was intended for market control. Today, only 7%.” In 2014, the CAP is, above all, a set of subsidies.

Trap of “antibiotics”

When we are there, the survival of crops without subsidies cannot be understood. However, the trade unions believe that this is a perverse system. Despite the fact that they want their dependence to disappear, the sector is essential today. “We take them as antibiotics,” says Garikoitz Nazabal, members of the EHNE of Gipuzkoa, “it takes you to fight the infection, but at the same time you weaken your defenses.”

In the opinion of Nazabal, the baserritars should not live from the aids, but from their work, “and after all that is to produce food for the citizens”. On the one hand, these products must be marketed at a price that is affordable for all citizens, and on the other hand, they must have prices that safeguard the future of farmers. “But that scheme no longer works,” Nazabal laments.

In the Spanish State, the price of farmers for their products increased very little between 2000 and 2012, while the Food Consumption Price Index rose by 50%. On the path of producers towards consumers there are intermediaries that are increasingly appropriating the cake. A report prepared by Veterinarians without Borders in 2011 highlights that the final price of food in the Spanish State is, on average, 4.5 times higher than that of producers. PRESIDENT. — The next item is the joint debate on the following motions for resolutions: Andoni García de EHNE-Bizkaia agrees with him: “On average, 30% of what baserritarras earn comes from subsidies, and in some sectors it can reach 70%. Imagine what it would be if you took off...”

Aid scheme to the detriment of the smallest

Although essential, EHNE-Bizkaia considers CAP aid – not all – poisonous, “because on its behalf artificially low prices are still justified for farmers”. Finally, the aid patch is not enough for many small, desperate baserritarras to put aside their activity.

In short, it is benefiting from large concentrations of land and industrial agriculture, as the distribution of subsidies is not at all balanced: more land, more aid. According to a recent study by the Transnational Institute, in 2011, 1.5% of European farms, the largest, were made with a third of the aid. In the French State, 44% of the aid was for 13% of households. And 75% of Spanish state aid accounted for 16% of beneficiaries. This privileged minority is mostly made up of large food industry companies and large landowners, including some of the highly renowned characters who frequently appear in the pink press covers.

The two pillars of the CAP

Imbalances do not end there. However, before proceeding further, some details on the subsidy scheme should be explained. For this we will use the explanation given to us by Mixel Berhokoirigoin: “The CAP’s support for crops is organised in two columns. From one state to another, but in general, in the EU, 80% of the aid is for the first column and 20% for the second. This second point relates to territory, quality, conservation of biodiversity ... They have a social objective, they reinforce territorial and environmental perspectives, they contribute to mountain cultivation, to biology ... The first pillar is support for production capacity, measured in hectares or in number of animals, linked to the grandeur of the farmhouse and without any other justification, or with little justification”.

This lack of justification referred to by Berhokoirigoin is called decoupling. When the market control mechanisms of the CAP began to weaken in 1992, aid to compensate farmers for losses was linked to production. In other words, the recipient had to prove that he was producing food; in other words, it was coupled aid. That was the beginning of change, but the trade unions believe that it was above all the reforms of the early years of this century that brought the sector upside down. “It was then that it really began to despise the price,” says Andoni García, “public intervention became even smaller and aid started to decouple.” Decoupling means that there is no need to justify any agri-livestock or livestock activity in order to qualify for subsidies, or that it is sufficient with very low activity.

In the Spanish State, a quarter of the total income of agriculture is sufficient to be considered as a professional farmer. Little, in the opinion of Xabier Iraola, of the ENBA trade union. Like the EHNE Confederation and the EHNE-Bizkaia, ENBA considers that the number of people eligible for aid under the first column, also known as direct aid, should be much smaller. “But in Madrid there are political interests to continue subsidising landlords of all life,” Iraola said. For his part, Andoni García considers that in the Spanish State – many others in Hego Euskal Herria- only one third of the recipients of decoupled aid should be entitled to it by themselves. “A significant fact: There are about 900,000 recipients in the State, over 300,000 of whom are already retired.”

On the other hand, decoupling is not total. The first pillar of the CAP has maintained a number of production-linked aids, but only for certain sectors: milk and beef, sheep, beet, rice, protein cereals (soya, wheat, barley...). The others are excluded from Brussels, and this is considered unfair by EHNE-Bizkaia, although most farmers in the Basque Country work in areas eligible for aid.

The first column is paid by the EU as a whole, and as far as the Basque Country is concerned, the distribution of the money is decided from Madrid and Paris. Support under the second pillar is financed equally between Brussels and local authorities. The Basque trade unions are now negotiating with the CAV institutions, Navarre and Aquitaine their working conditions, which will enter into force during 2015.

In Iparralde, progress has been made in some areas, according to Mixel Berhokoirigoin. In the case of the South it is early to say nothing, but it is clear that, at least, the aid in the second column is not considered to be antibiotics or poisonous. “The EU should increase the amount of money for the second column,” García told us, “because that is what has to do with the reality of the sector, which promotes employment, which supports those in difficult conditions… In short, a more sustainable model”. EHNE-Bizkaia is clear on the way to strengthen funding for the second pillar: to stop giving first-column aid to non-professional farmers.

In the opinion of Mixel Berhokoirigoin, “it could be said that the two pillars of the CAP are confronted: the first seeks to fix what breaks, the first because it is given without social criteria, and brings with it the disappearance of employment and desertification”. The problem is that 80% of the budget is destined to fail, and only 20% is destined to solve it. In the view of the Basque trade unions, the saddest thing is that when this latest reform of the CAP was put on the table two or three years ago, the European Commission presented a very hopeful speech, which was utterly critical of the policies at the time. “In the end, however, they have not satisfied the hope they have generated,” says Andoni García, disconsolate. Berhokoirigoin is clear that the main reason why they have been gradually distorted (environmental care, fairer distribution of aid...) is the lobby, the lobby always.

Women farmers, the most excluded

In 2012, researchers Isabel de Gonzalo and Leticia Urretabizkaia published Las mujeres baserritarras; analysis and future perspectives from Food Sovereignty (Baserritarras Women: analysis and future perspectives from the perspective of Food Sovereignty). In the first part of the book, Isabel de Gonzalo talked in detail about the history of the CAP and its current influence on the cultivation of Hego Euskal Herria, especially from the gender perspective. The author stressed that the reforms carried out since 1992 have particularly harmed women farmers. Particularly as from 2003.

In the words of De Gonzalo, approximately a decade ago the entry into force of decoupled subsidies, that is, linked not to production but to the mere ownership of land or livestock, benefited large crops and, presumably, small and traditional production models. To the models in which the majority of women farmers are found.

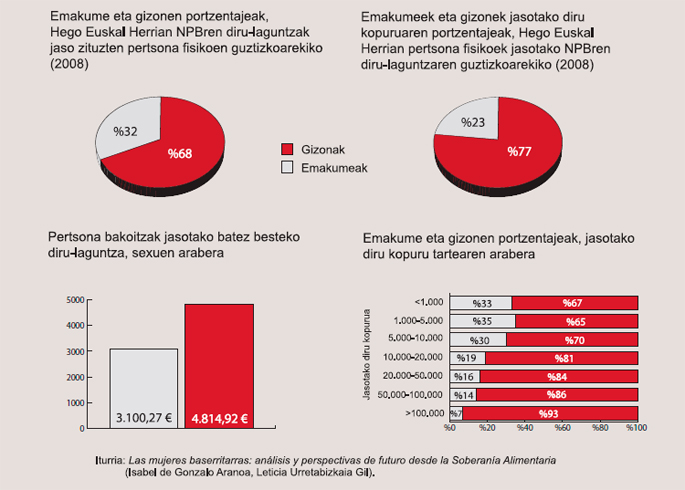

In his study, De Gonzalo analyzed from a gender perspective the aids of the NPB in Hego Euskal Herria, for which he had to cope with the lack of information. In fact, data on the distribution of these aids are not usually disaggregated by sex. “The lack of data has an important political significance,” he wrote, “because it is impossible to measure whether the criterion of equality in the distribution of subsidies is being taken into account.” The investigator had to go to the list of recipients of the aid and check one by one the name and last names of each of them. But he had to settle for the 2008 figures, as the data protection legislation in force since that year prevented him from knowing the identity of the recipients.

De Gonzalo recomputed the graphs with the 2008 data, the same ones that appear on the next page. It is clear that in the case of natural persons – it must be borne in mind that some recipients are companies, not individual ones – women receive less CAP subsidies than men. And the higher the amount of aid, the lower the percentage of women it receives, as shown in the fourth graph.

Data for 2008 are not the most recent, however. Exceptionally, the Government of Spain published some data for 2012 with various classifications by sex. For recipients of European aid, the percentages are practically the same as in 2008: In Hego Euskal Herria, 68% of the natural persons who received direct CAP aid were men.

Udaberrian orain dela egun gutxi sartu gara eta intxaurrondoa dut maisu. Lasai sentitzen dut, konfiantzaz, bere prozesuan, ziklo berria hasten. Plan eta ohitura berriak hartu ditut apirilean, sasoitu naiz, bizitzan proiektu berriei heltzeko konfiantzaz, indarrez, sormen eta... [+]

Ohe beroan edo hotzean egiten da hobeto lo? Nik zalantzarik ez daukat: hotzean. Landare jaioberriek bero punttu bat nahiago dute, ordea. Udaberriko ekinozio garai hau aproposa da udako eta udazkeneko mokadu goxoak emango dizkiguten landareen haziak ereiteko.

Duela lau urte abiatu zuten Azpeitian Enkarguk proiektua, Udalaren, Urkome Landa Garapen Elkartearen eta Azpeitiako eta Gipuzkoako merkatari txikien elkarteen artean. “Orain proiektua bigarren fasera eraman dugu, eta Azkoitian sortu dugu antzeko egitasmoa, bere izenarekin:... [+]

Itsasoan badira landareen itxura izan arren animalia harrapari diren izaki eder batzuk: anemonak. Kantauri itsasoan hainbat anemona espezie ditugun arren, bada bat, guztien artean bereziki erraz atzemateko aukera eskaintzen diguna: itsas-tomatea.

Aurten "Israel Premier Tech" txirrindularitza talde israeldarra ez da Lizarraldeko Miguel Indurain Sari Nagusia lasterketara etorriko. Berri ona da hori Palestinaren askapenaren alde gaudenontzat eta munstro sionistarekin harreman oro etetea nahi dugunontzat, izan... [+]

Sare sozialen kontra hitz egitea ondo dago, beno, nire inguruan ondo ikusia bezala dago sare sozialek dakartzaten kalteez eta txarkeriez aritzea; progre gelditzen da bat horrela jardunda, baina gaur alde hitz egin nahi dut. Ez ni optimista digitala nauzuelako, baizik eta sare... [+]

Bada Borda bat ilargian. Bai, bai, Borda izeneko krater bat badu ilargiak; talka krater edo astroblema bat da, ilargiaren ageriko aldean dago eta bere koordenadak 25º12’S 46º31’E dira; inguruan 11 krater satelite ditu. Akizen jaiotako Jean Charles Borda de... [+]

Donostiako Amara auzoko Izko ileapaindegi ekologikoak 40 urte bete berri ditu. Familia-enpresa txikia da, eta hasieratik izan zuten sortzaileek ile-apainketan erabiltzen ziren produktuekiko kezka. “Erabiltzaileen azalarentzat oso bortzitzak dira produktu gehienak, baina... [+]