It is becoming increasingly clear that the era of revolutions is not over. And it is clear that the global revolutionary movement of the twenty-first century will not be so much a movement that has its origin in the Marxist tradition, nor in limited socialism, but in that of anarchism.

Everywhere, from Eastern Europe to Argentina, from Seattle to Mumbai, anarchist ideas and principles are creating new approaches and radical dreams. Their manifestations are often not called anarchists. There are many other names: autonomy, anti-authoritarianism, horizontality, zapatism, direct democracy... However, in all places there are the same basic principles: decentralization, volunteerism, mutual assistance, social networks, and above all, rejection of any idea that says that the objective justifies the means, and even less than that the objective of the revolution is to take the power of the State, with the pistol in hand to impose its own point of view. Above all, anarchism, as an ethics of practice – the idea of building a new society in the “inner shell of the old society” – has become a basic inspiration for the so-called “movement of movements” (of which the authors are part) and aims from the very beginning, rather than conquer the power of the State, show, delegitimize and destroy the mechanisms of power, while in them more and more participative management is gained.

There are several reasons to explain why anarchist ideas are attractive at the beginning of the twenty-first century: the most obvious are the errors and catastrophes that have occurred in the twentieth century as a result of the numerous efforts made to overcome capitalism by controlling the apparatus of government. More and more revolutionaries recognize that the “revolution” will not come in a great apocalyptic moment, of something global like the Winter Palace, but of a long process that has been happening in most of human history (although, like most things, it has accelerated in recent times), with flight and flight strategies, as well as dramatic confrontations and that will never end definitively.

It’s a little confusing, but it offers great consolation: you don’t have to wait to “reverse the revolution” to start to get the idea of how real freedom should be. As the collective Crimethink says, the biggest propagandist of contemporary American anarchism: “Freedom exists only at the time of revolution. And those moments are not as extraordinary as you think.” For an anarchist, in fact, trying to create experiences without alienation is a true democracy, an ethical imperative; only by making the organization now in the way of oneself – offering it a broad approximation of how at least a free society would work in reality, how we could all live once – can you ensure that we will not fall back into disaster again. Unhappy revolutionaries, sad revolutionaries, who sacrifice all pleasure for the cause, can only create sad societies, sad societies.

These changes have been difficult to document because so far anarchist ideas have received little academic attention. There are still thousands of Marxist scholars, but there are hardly any anarchist scholars. This difference is difficult to analyze. In part, of course, it is because Marxism has always had a certain affinity with the academic world and anarchism did not: Marxism, after all, was the only great social movement invented by a doctor. Most of the references in the history of anarchism recognize that it resembles Marxism: anarchism is presented as an invention of 19th century thinkers (Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin…) and served to inspire working-class organizations, engaged in political struggles, divided into currents…

Anarchism, in conventional history, presents itself as a poor relative of Marxism, a little theoretically but ideologically compensated, perhaps with passion and truthfulness. The analogy is certainly a bit forced. The founders of anarchism didn't believe they invented anything new. Its basic principles – mutual assistance, voluntary membership, equal decision-making – are as old as humanity. The same applies to the rejection of the state or any kind of violence, inequality or structural domination (anarchism literally means “no director”) – even with the assumption that all these ideas are to some extent in contact and mutually support each other. All this was not seen as an extraordinarily innovative doctrine, but as a trend that has remained in human thought, which cannot be understood within a single general ideological theory.

It's partly like a faith: to believe that most of the forms of neglect that make power necessary are actually the effects of power itself. In practice, however, there is a permanent questioning, each of the forced relationships of human lives, the attempt to identify each of the hierarchical relationships, and the challenge of justifying themselves, and whether they cannot – as in most cases – limit their power, so as to increase people’s freedom. A Sufi can say that the real heart behind all religions is Sufism; for, to the same extent, an anarchist can argue that anarchism is the desire for freedom behind all political ideologies.

It is easy to find the founders of Marxist schools. As Marxism emerged from Marx’s mind, we have the Leninists, the Maoists, the Althussers… (see how the list begins with the heads of state and is diversified in the French professors – who in turn can generate their own currents: Lacanenses, Foucaultians…).

On the contrary, anarchist schools are almost always born of some principle of organization or practice: anarcho-syndicalists and anarcho-communists, insurrectionalists and platforms, cooperatives, individualists, etc.

Anarchists are distinguished by what they do and by the way they organize themselves for this action. This has always been the case, and most of his time has been spent thinking and debating anarchists. They have never been too interested in general philosophical or strategic issues of concern to the Marxists, for example, are farmers a potentially revolutionary class? (Anarchists think that's something farmers themselves have to decide) or, what's material possession? Anarchists are more likely to discuss what is the truly democratic way of organizing an assembly and to what extent the organization ceases to be an instrument for all people and begins to erode individual freedom. Is “leadership” really bad? At the same time, they ask themselves about the ethics of opposing power: What is the right action? Would anyone have to condemn another for murdering a head of state? When is it right to throw a brick?

Marxism, in this way, has had a tendency to have an analytical or theoretical discourse on the revolutionary strategy. And anarchism has gone on to have an ethical discourse about revolutionary practice. The result: Marxism has produced brilliant theories about praxis and in general it has been the anarchists who have worked with it.

At the moment, there is a certain rupture between the generations of anarchism: between those who received their political formation in the 1960s and 1970s, and often have not stirred up the sectarian customs of the last century, or those that simply work in those terms, and among the youngest activists, many more informed, among others, with indigenous, feminist, environmentalist or cultural revisionist ideas. The former are organized through the Anarchist Federations such as IWA1 NEFAC2 or IWW3. The latter mainly work on networks of the global social movement, such as the Global Action of Peoples, which brings together anarchist collectives from Europe and elsewhere, starting with the great entrepreneurs of New Zealand, such as fishermen from Indonesia or the Canadian postal workers union. This second group, which we can ambiguously call “anarchist with lower case letters,” is now the first. But this is often hard to say, because many of them don't shout loud about their affinities. There are not many who take the principles opposed to sectarianism and in favour of expansion so seriously, who refuse to qualify themselves as anarchists for the same reason.

But the three fundamental ideas that appear in all the manifestations of anarchist ideology are anti-state, anti-capitalism and prefigurative politics (i.e., forms of organization that resemble a world we want to create consciously. Or, as an anarchist historian of the Civil War of 36 said, “not only the effort to think of ideas, but also of future facts”). If that exists in any group, from the “jamming collectives” to Indymedia, we can all consider them anarchists in this new sense. In some countries, there is only a very limited relationship between these two generations that exist at the same time, especially to follow what each one is doing, but not much more.

One of the reasons is that the new generation is much more interested in developing new ways of working than in arguing for the finest points of ideology. Among them, the most important has been the development of new forms in the decision-making process, at least the beginning of an alternative culture of democracy. Among them, the most spectacular are the well-known American “popular meetings” in which thousands of entrepreneurs coordinate large-scale events without a formal steering structure.

It's actually a little bit misleading to call these forms "new." One of the main sources of inspiration for the generation of the new anarchists are the autonomous municipalities Zapatistas of Chiapas, based on the speaking communities of Tzeltal and Tojobal, which have used consensus processes for thousands of years – now revolutionaries have adapted them to ensure that women and young people have a voice. In North America, the “consensus process” emerged mainly in the feminist movement of the 1970s, as part of a broader reaction to the male leadership style of the New Left of the 1960s. The idea of consensus was taken from the Quakers and they say they were inspired by the Six Nations, as well as by other practices of the Native Americans.

Consensus is often misunderstood. Criticisms are often heard that consensus would lead to asphyxiation of conformism, but hardly ever is the criticism of someone who has seen the process underway, or at least the processes led by qualified and experienced moderators (in Europe there is little tradition for this kind of thing and some recent experiments have been a little “raw”). Indeed, the hypothesis used is that no one can really bring anyone absolutely to their point of view, and probably should not. Instead, the objective of the consensus process is to let a group decide as long as common actions are carried out. Instead of voting on top-down proposals, proposals are drawn up and revised and reinvented, there is a process of compromise and synthesis, to something that everyone can accept. When we reach the final stage, when we come to the moment of “finding consensus”, there are two levels of possible objections: you can stay “aside” and that means “I don’t like this and I won’t participate in it, but I won’t stop anyone else from doing it”; or “blocking it”, which has the effect of a veto. It can block a proposal, but only if it believes that it contravenes the basic principles or reasons of being of the group. It could be said that the role that the US Constitution gives to the Supreme Court, which can reject legal decisions that violate constitutional principles, is left to anyone here, if it really has the courage to deal with the will of the group (although there are also ways to combat unjustified blockages).

We could go on for a long time talking about very sophisticated and surprisingly sophisticated methods that have been developed for this to work; about consensus forms adapted for very large groups; about how consensus reinforces the principle of decentralization, ensuring that no one wants to present to the large groups proposals if it is not necessary, about ways to ensure gender equality and to resolve conflicts... The key is that direct democracy is a form of the middle class that we normally associate with that name. With more and more international contacts between diverse movements, including indigenous groups from Africa, Asia and Oceania with radically different traditions, what we are seeing is: a global review of what the word “democracy” should say, which is as far away as possible from neoliberal parliamentarism that is currently promoting powers in the world.

It is again difficult to follow this spirit of synthesis by reading most of the existing anarchist literature, as most of its forces are the people who employ for theoretical issues – most likely the people who support the old sectarian dichotomous logic – rather than using them in the new forms of practices that are being created. Modern anarchism is full of countless contradictions. While anarchists with minuscule A acquire ideas and practices learned little by little from indigenous allies and integrate them into their forms of organization and in alternative communities, the main clue of written literature has been the birth of a sect of the Primitivists, a very controversial group that is committed to the total abolition of industrial civilization and, in some cases, to do the same with agriculture. However, it is only a matter of time that the old logic leaves the way free to something that is more closely related to the practice of groups based on consensus.

What would this new synthesis be? Some lines that would structure can already be recognized in the movement. I would emphasize the constant attention and diffusion to anti-authoritarianism, trying to move away from class reductionism “all the spaces in which domination is manifested”, that is, not only pointing out the State, but also gender relations; not only economic relations, but also cultural relations, ecology, sexuality and freedom, in each of the ways in which one can seek, and not only through the prism of the richer relationships.

This approach does not advocate an unlimited expansion of productivity, nor the idea that technologies are neutral, even if it does not give up technology per se. On the contrary, he sister with him and uses it when appropriate. It does not rule out the institutions per se, nor the political forms per se. It seeks to create new institutions and political forms of action and new society, incorporating new forms of meeting, decision-making, coordination, in a line that already works with related groups and structures of dialogue. And not only do they condemn the reforms per se, but they also struggle to define and achieve reforms that are not reformist, meeting the immediate needs of the people and trying to improve their lives here and now, until they reach greater achievements, at last, until a total transformation.

And of course, the theory will have to adapt to practice. To be fully effective, modern anarchism must bring together at least three levels: entrepreneurs, grass-roots organisations and researchers. The problem is right now, that anarchist intellectuals who want to overcome old customs – the Marxist drunkenness that still continues in much of the intellectual world – are not sure what their role should be. Anarchism has to be thoughtful. But how? To some extent the answer seems obvious. It shouldn't teach anyone, or put a chair, and less think of oneself in terms of a professor, but listen, explore and discover. To take the outside and make explicit the tacit logic that underlies the new radical practices. Make yourself available to entrepreneurs by offering information and showing the interests of the ruling elite, who are carefully hidden behind supposedly objective authoritarian speeches, rather than trying to establish a new version of the same. But at the same time, many recognize that intellectual struggle must reaffirm its role. Many have begun to point out that one of the basic weaknesses of the anarchist movement today is, for example, the discovery of the symbolic, the imaginary, and the forgetting of the effectiveness of the theory with regard to the times of Kropotkin, Reclus or Herbert Read. How can we move from ethnography to utopian visions – in ideals, encompassing all possible utopian visions? It's no accident that people who have recruited more anarchists in countries like the United States are feminist writers, like Starhawk or Ursula K. Like Le Guin.

This is happening as anarchists are recovering the experience of other social movements with a more developed set of theories, ideas that come from nearby circles, actually inspired by anarchism. Take, for example, the idea of participatory economics, one of the main anarchist perspectives, which is the traditional anarchist economy and which corrects it. The theorists of Rev. 4 propose not only two, but three different social classes in advanced capitalism: not only the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, but a “coordinating class” whose mission is to manage and control the production of the working class. This class brings together the hierarchy of basic managers and consultants and professional advisers you need for your control system, such as lawyers, engineers and important accountants. They maintain their class position thanks to their great monopoly on knowledge, qualifications and connections. As a result, economists and others working in this field have tried to create economic models that would dismantle the structural divisions between intellectual and physical workers. Now that anarchism has clearly become the center of revolutionary creation, those who propose such models are trying not to use precisely the anarchist flag, but to give importance to the degree of compatibility of their ideas with the anarchist views.

Similar things start to happen with the development of anarchist political conceptions. According, in this field classical anarchism already had an advantage over Marxism, which had never developed a theory about political organization. Many anarchist schools have often supported very specific social organizations, although on many occasions some disagree with others. However, anarchism as a whole has tended to promote those liberals that have been called “negative freedom” or “freedom of”, rather than “freedom for”. It has on many occasions welcomed this commitment as a sign of the plurality of anarchism, of its ideological tolerance or of its creativity. But in conclusion, there has been a lack of desire to go beyond developing small-scale organizational forms, and it has been believed that larger, more complex structures can be improvised in the same spirit.

There have also been exceptions. Pierre Joseph Proudhon attempted to provide a comprehensive perspective on how a libertarian society should function. It is considered a failed attempt in general, but it shows the way to more developed approaches such as the “libertarian municipality” of the Social Ecologists of North America. There is rapid development, for example, on the principles of worker control – highlighted by the Parecon team – and on how to balance direct democracy, underlined by the Social Ecologists.

However, there are many details to be defined: What is the anarchist’s positive institutional alternative to current legislation, courts, police and various executive agencies? How can we offer a political approach that takes account of its implementation, allocation and compliance and also shows how to do each of these paragraphs in non-authoritarian ways – not only to offer long-term hope, but to give an immediate response to the electoral system, the legislative system and the judicial system, and so on to many strategic options? Obviously, there can never be a partisan line on this in anarchism, but among the anarchists of the minuscule a is a general feeling that we would need, at least, many concrete views. Among the real social experiments that have been carried out in places like Chiapas and Argentina and with the efforts of anarchist activists/“scholars”, with forums such as the Network of Planetary Alternatives or the Post-Capitalist Life that was created recently, it is possible to begin to locate and collect examples of successful economic and political forms. It is a long-term process. But, well, the anarchist century has only just begun.

* David Graeber and Andrej Grubacic are anthropology professors at the Goldsmiths College of London and the Institute of Integral Studies of California, respectively.

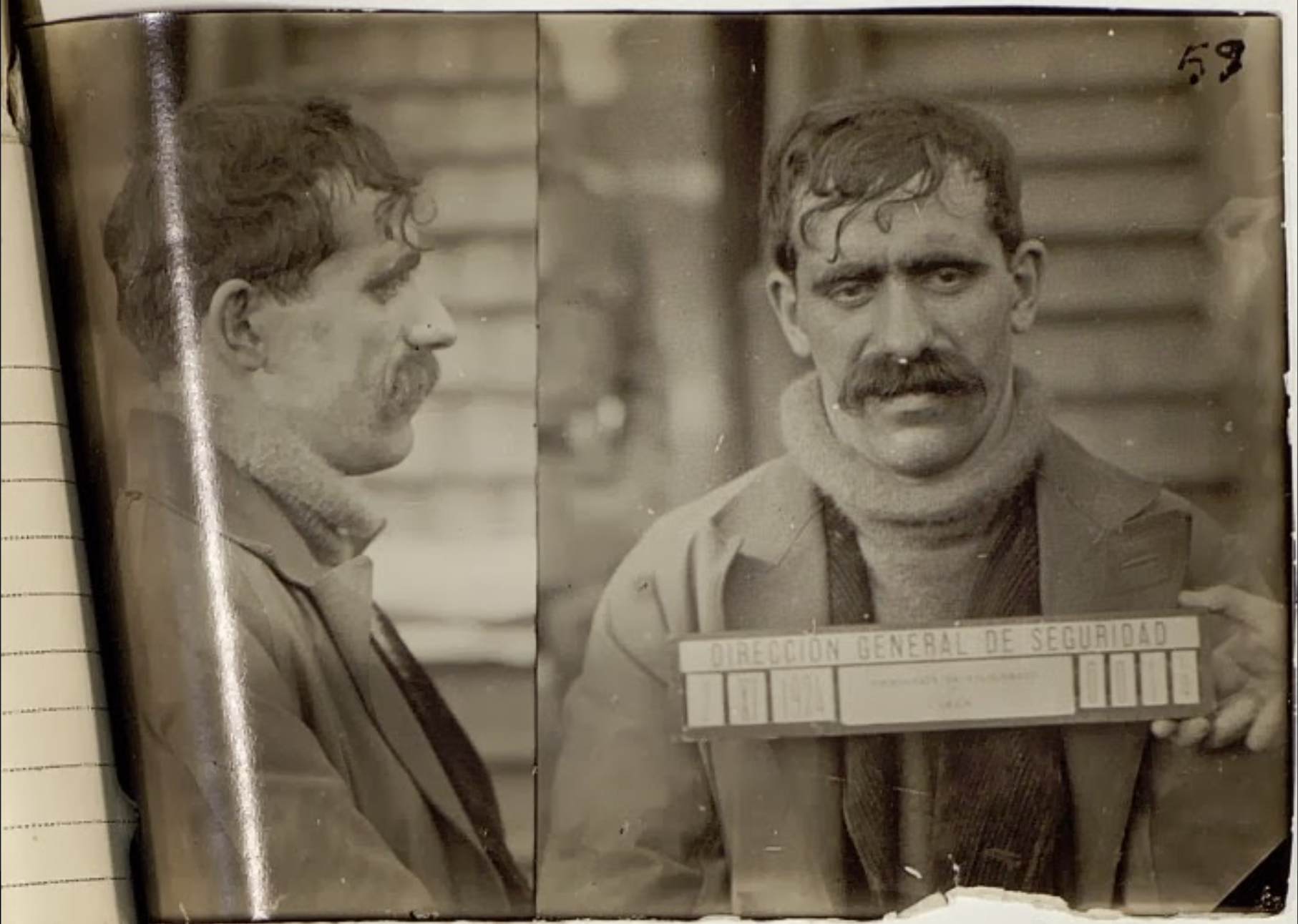

Born 7 November 1924. A group of anarchists broke into Bera this morning to protest against the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and to begin the revolution in the Spanish state.

Last October, the composition of the Central Board was announced between the displaced from Spain... [+]

Henry D. Thoreau ::Desobedientzia zibila

Potxo Edizioak

orrialdeak ::77

prezioa ::10€