Charming architect of Franco

- The architect Pedro Muguruza (Elgoibar, 1893-Madrid, 1952) was a national advisor, director general of Post-War Architecture, head of Falange and prosecutor of the Spanish Courts during the dictatorship. He is the author of the Valley of the Fallen, Sacred Hearts of San Sebastian and Bilbao, among others. He is a favorite son of Elgoibar and a street has its name yet. He is considered an adoptive son in Hondarribia.

It transformed many landscapes of Euskal Herria, affecting a part of the history of our people and also of Spain. Franco's preferred architect was the elgoibartarra: Pedro Muguruza Otaño. “He was the architect of the regime, of reference.” “The symbols attached great importance to Franco and, in addition to a total political consensus, Muguruza joined the artistic style of the dictatorship,” explained historians Jesús Gutiérrez and Iñaki Egaña, respectively. The website of the Francisco Franco Foundation also clearly states: Pedro Muguruza, head architect of the Caudillo.

The elgoibartarra is already the author of several famous buildings before the war. In 1925 he built the Palace of the Press of Madrid, and several important dwellings of the streets Alfonso XII and Felipe IV, as well as the Teatro Real; the renovation of the Station of France of Barcelona was made by his hand.

In 1936, after the outbreak of war, he “promoted the National Uprising and became a member of Phalanx. It had a very good relationship with Franco,” says the web of the foundation of Franco. Muguruza took power in the post-war period, as Falange put him at the head of the General Directorate of Architecture. According to Gutiérrez, “Muguruza joined the Francoist ideology. On the one hand, they saw that he was a professional, and on the other, they had an obligation to take on people like this. Think about the number of intellectuals and high-level professionals who died or exiled!”

As if it were not enough, the post-war situation in Spain was regrettable: most of the infrastructures were destroyed, the cities and towns that had been in front of them were destroyed… There was much to do. Thus, the take-off of the elgoibartarra within the regime was spectacular in the first two bloody decades: He was appointed National Adviser to the Government and Prosecutor of the Courts of Spain in 1943.

Exalting franchises, forgetting democracies

Given that this is such a significant route, how is it possible that the architect is not currently well known in the Basque Country? “It’s rare that it hasn’t been mentioned so far, perhaps because Elgoibar has been a stranger to outsiders,” replied Eibarrés historian Gutiérrez. For its part, Egaña is clear that: “Franco was like an octopus: the heads are well known, while other agents are completely unknown. In the end, current generations make an interpretation of history, but without going into detail: Zuloaga, Iturrino, Sánchez Mazas… Many of us do not know their political trajectory well.”

To clarify more, we turn to the Ahaztuak association 1936-1977 in defense of historical memory and ask our colleague Martxelo Álvarez: “These ‘second-line’ men have been relegated, because we have usually settled on people with clearer political or military responsibilities. Then, of course, as a person investigates a particular name, we are discovering what he did… From Muguruza we didn’t have much idea.”

Interestingly, the historical memory expert Juan Ramón Garai did not know Muguruza, and as soon as the Franco profile of the architect appeared, Alejandro Goicoechea, the author of the War Iron Belt, and then the one who went to the fascist side, came to his head. “Despite being very good artists, they both decided to wager on the Francoists and took advantage of their environment to grow themselves. They don’t deserve a street name,” he said firmly.

The lack of knowledge of the architect by Álvarez and Garai, committed to historical memory, is a clear example that the recovery of the forgotten past still has a long way to go. Taking into account that Muguruza is the author of the images of San Sebastian and the Sacred Heart of Bilbao: “In the one in Bilbao and in the one in Donostia he was free to do what he wanted,” Egaña stressed.

The Sacred Heart: Diffuse Francoism

These gigantic images that are found in the heart of the two capitals of Euskal Herria, today many people do not link them to the dictatorship. Álvarez stressed that “we have two references to the imposition of nationalcatholicism, but being religious figures, this is blurry today”. If you don’t analyze what he built and its causes, you don’t realize it.”

The Sacred Heart of Bilbao dates from 1927. In any case, it caused a scuffle: "In times of the Republic, the City Hall gave the order to take him away and there was a great debate. In early 1933, it was voted in an assembly and the supporters of abolishing it (Socialists and Republicans) got the majority, so their dissolution was ordered,” Egaña explained. However, the defenders of the preservation of the image subsequently won the lawsuit in the courts and the matter was suspended.

The one from Donostia-San Sebastián, however, is something later: “At the time of the Republic a huge campaign was organized to raise funds from the citizens, but at the end of the day the City Hall refused the project,” the historian of Donostia stressed. After the Franco coup, they recovered the project and carried it forward in 1950. In the first legislature of democracy, the debate in the city was revived, but it was also suspended.

So things, what should be done with those two images? Egaña considers that the one of San Sebastian is “a clear Francoist symbol”, “which had the support of the governments of the city and Madrid; all the freedom and support of the regime, because in the dictatorship it could not open its mouth”. On the contrary, the Donostian chronicler

Javier María Sada should not qualify as a symbol of Franco: “The project is old and, although it is of national-catholic ideology, if we have to eliminate it, we would also have to demolish some hospitals, institutes and schools that were inaugurated in Franco and that were built according to its policy. Everything or nothing.” Sada added that at the moment it is no longer "a religious symbol, but the aesthetic totem of the city".

“I was watching Donostia from Martutene prison for eleven months,” says Garai, remembering the years when he was a member of ETA in 1969. “Then I was in favor of taking me off, now I have no opinion. There’s something more important to do today: Francoist streetlights and Valley of the Fallen, for example.” Álvarez adds to these words: “Pedagogy should be done so that people know why they did it, but they are on a different level from the Valley of the Fallen, even if they are the work of the same architect.”

Elgoibar City Hall will keep the street

Pedro Muguruza was named Elgoibar's adopted son in 1943 and his favourite son on 8 August 1946. In addition, a village street bears its name. According to the mayor, Alfredo Etxeberria, “we have not entered into an in-depth examination in the account of the preached child; we have not raised it; it is a work that needs to be done, but it is not urgent”. Shortly thereafter, the Elgoibar City Council announced that it would withdraw the Franco plates from the buildings and submit a motion to examine whether the designation of Muguruza should be suspended. On the contrary, it will keep the alley intact.

The member of the association for historical memory Elgoibar 1936, Hodei Otegi, has strongly denounced the event: “A few years ago, we asked the mayor directly to withdraw the street name, but he didn’t give a strong answer, it wasn’t included in that question.” But Etxeberria makes it clear. “We have no intention of changing the name of the street: he was an architect of his time, was important, was civil and not military. In addition, in the case of public offices of political or business relevance, the Basque Government recommends changing the name of the street, but local corporations can maintain the name. It is not obligatory to comply, every city council must decide its street.” As an example, the mayor has put

the Plaza Navarra de Elgoibar, which has regained its name of origin: Plaza de Kalebarren. “We have changed because in September 1936 the Navarra battalion entered, because they were military. It was very remarkable, it has another importance. However, it seems to me that we have to give another reading to Pedro Muguruza’s street.”

In addition, the President of the City of Elgoibar asked the following question: “Not everything is black and white. In the event that those who live on Pedro Muguruza Street are asked if they change their name, they will see what they say. Even though the street is renamed, people would always call Pedro Muguruza. In addition, there are things that you can update, change the reading, give it another meaning. Its history must also be valued. For example, the reason for the great cross that is on the top of Morkai and that has always appeared in the shield of the Mountain Society of Morkai.” Another key to not having changed, perhaps, has been given to us by Otegi: “The case is that the testimonies of the people do not speak badly of Muguruza, and we have also found some case of him who brought his family member out of prison, etc. Well, that double game of always: incarcerate yourself first and then say goodbye.”

The Elgoibar association 1936 also recalled that in eleven streets the plaque of the dictatorship persisted and in 2008 a letter was sent to the City Hall to withdraw the symbols according to the Law of Historical Memory. “The Basque Government has just sent us criteria – said Mayor Etxeberria, before the City Hall decided to remove the plates – and our idea is to recommend to the neighbours and neighbours what kind of plates are in their construction and to remove them. Then, they will have to decide whether or not they will remove it. At Elgoibar we are gradually taking off, fortunately the plates are not large.”

In Hondarribia, adoptive son

But Muguruza not only has the street in his village, but also in Madrid. In Hondarribia he is considered an adoptive son for having built several buildings. The councilor of the town hall, Lupe Olaskoaga, points out that the architect is “well known” in the town: “He’s done a lot.” Its importance in Franco tells us: “I have no idea about it. I can't say anything, I don't know." Here we ask if we have to talk to another person from the City Hall: “They haven’t told us anything about it, so I think if you call another, he’ll tell you the same thing.” Questioned on the subject, here is the answer: “We’ll talk about it, but nothing else.”

What to do with characters like Pedro Muguruza? Egaña has made it clear that the characters of the dictatorship era should be "deepened". In fact, “his work should be taken into account in its entirety, being in context, since in most cases his political part is blurred. The works were carried out because they had an opportunity in Franco, which most artists did not have, as they were in exile. Some, forced, but others, with all their will, formed a branch of the totalitarian system. We should be much more honest about it.”

Álvarez goes further: “With this study you are doing and with other associations supporting historical memory we also know those people who have been hidden. Soon we will present proposals for the elimination of Franco symbols and nomenclatures in different municipalities, and now, knowing that of Muguruza, we will also study and present his figure in Elgoibar”.

Pedro Muguruzak ez zuen soilik arkitektura zibilean parte hartu, frankismoaren eraikin handi eta sinbolikoena ere osatu zuen: El Valle de los Caídos. “Bere gain hartu zuen eraikuntzaren ardura eta egilea ere izan zen” dio Jesús Gutiérrez historialariak. “Francoren proiektu pertsonala zenez, diktadurako hainbat eragile eta artistek hartu zuten parte; Muguruzarena gurutzea da”, zehaztu du Iñaki Egaña historialariak.

Gerraosteko Euskal Herria eta Espainia suntsiturik zeuden eta berreraikitzeko agindua eman zioten Muguruzari. Hala, Irun, Hondarribia, Zarautz eta Elgoibarren eraikin zibil asko egin zituen. “Erronka garrantzitsua zen, baina kanpora begira, Valle de los Caídos zen inportanteena”, azpimarratu du Gutiérrezek. Izan ere, jende askok ez daki Franco eta Primo de Rivera faxistez gain milaka errepublikar lurperaturik dauden mausoleo horren egilea denik. “Euren bakea sinbolizatzen zuen, eta garaile eta galtzaileak zeuden lurperatuta”, gogoratu du Gutiérrezek.

Nolanahi den, memoria historikoaren inguruan iritzia bakarra da: “Orain frankisten monumentua da, beraz, Primo de Rivera eta Franco hortik kendu behar dira”, dio Juan Ramon Garai idazleak. Bat dator Martxelo Alvarez Ahaztuak 1936-1977ko elkarteko kidea: “Guk betidanik defendatu dugu; lehenik, Franco eta Primo de Riveraren gorpuzkinak atera beharko lirateke, bigarrenik, ahal dela bertan metaturik diren milaka errepublikarren gorpuzkinen identitatea jakin behar dugu, senitartekoek gorpuzkinekin zer egin erabakitzeko. Hirugarrenik, erregimen frankista zer izan zen salatzeko zentro bilakatu dezatela, memoria demokratikoa defendatuz. Eta azkenik, sinbologia eta pedagogia aldetik garrantzitsua da haran horretako gurutze erraldoia eraistea”.

Azkenean, frankismoaren monumenturik sinbolikoena ezin izan zuen amaiturik ikusi Muguruzak: 1959an inauguratu zuten, baina elgoibartarra jadanik hilik zen; pixkanaka areagotzen zihoakion paralisi batek eraman zuen 1952. urtean.

Bilbo, 1954. Hiriko Alfer eta Gaizkileen Auzitegia homosexualen aurka jazartzen hasi zen, erregimen frankistak izen bereko legea (Ley de Vagos y Maleantes, 1933) espresuki horretarako egokitu ondoren. Frankismoak homosexualen aurka egiten zuen lehenago ere, eta 1970ean legea... [+]

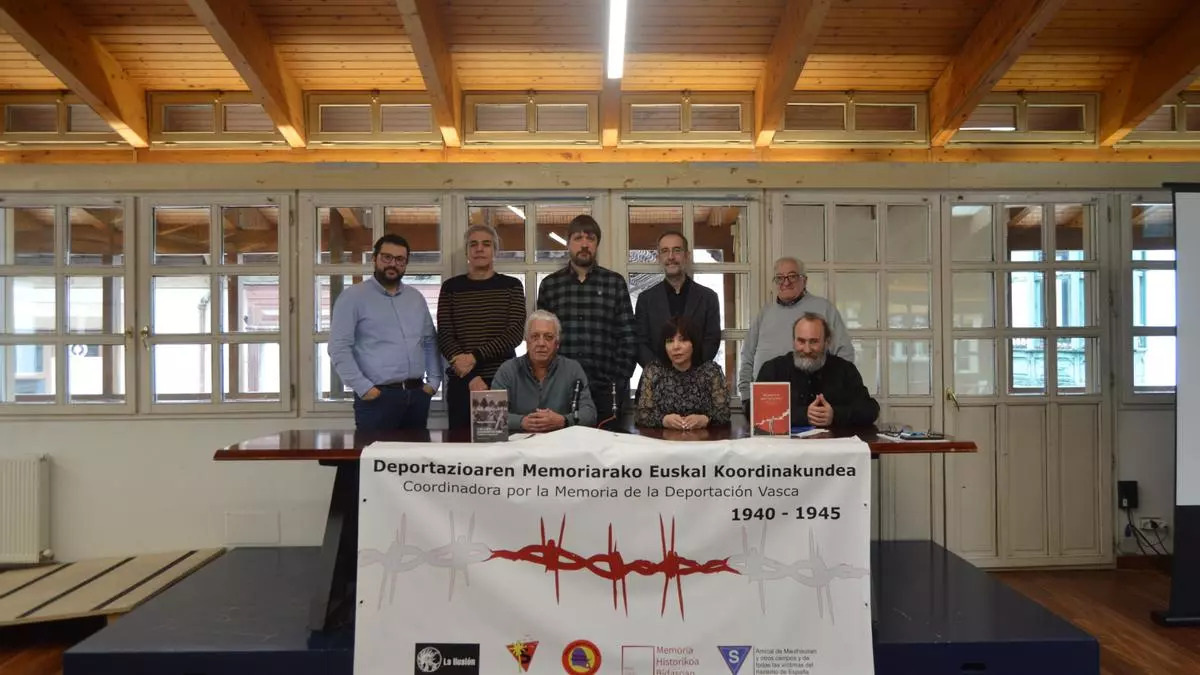

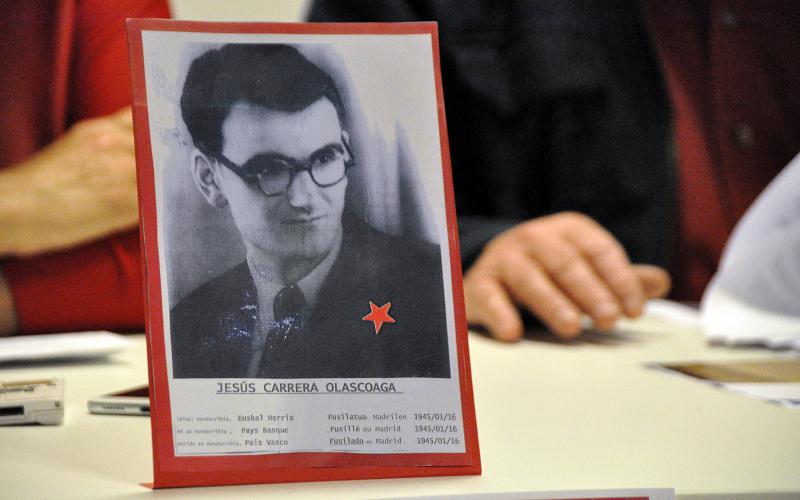

Deportazioaren Memoriarako Euskal Koordinakundeak aintzat hartu nahi ditu Hego Euskal Herrian jaio eta bizi ziren, eta 1940tik 1945era Bigarren Mundu Gerra zela eta deportazioa pairatu zuten herritarrak. Anton Gandarias Lekuona izango da haren lehendakaria, 1945ean naziek... [+]

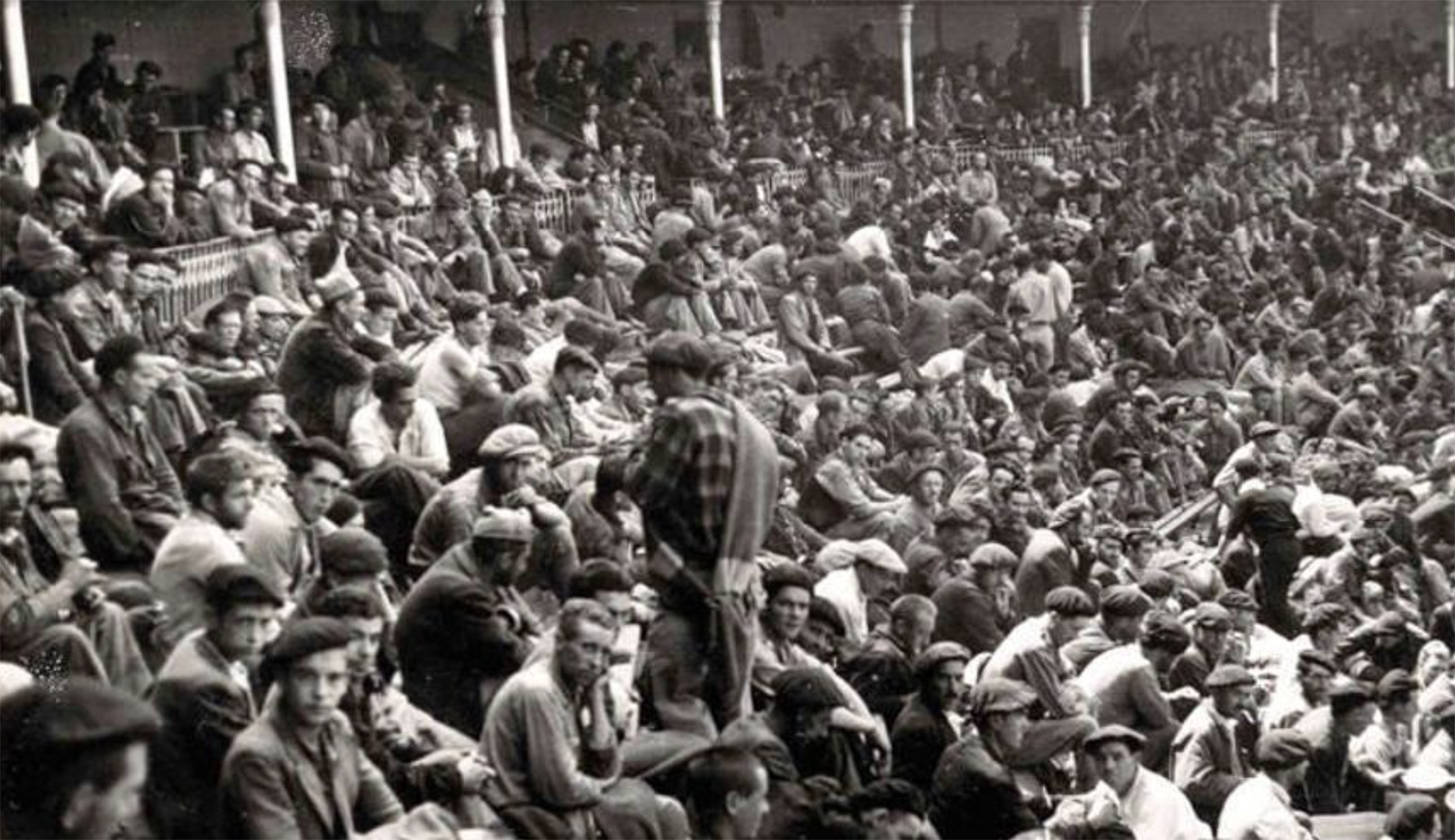

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]