When people are the mainstay of the economy

- On September 15, 2008, workers took their dreams and concerns out of Lehman Brothers in weak cardboard boxes that showed the failure of the four-decade neoliberal model founded on credit. No one knows what post-capitalism will be, perhaps a “foreign country”, as Josep Fontana says. But the humble people, as usual, have sought alternatives to escape the claws of the banks, not to fall into the hole of unemployment. One of the principles of the social economy is to prioritize people and social purpose to capital. Participation of workers, fair redistribution of benefits, internal democracy, self-organization, sustainability...About 10% of the economy of the Basque Country is located in these parameters, or in some of them, and is expanding, due to the diversity of the possibilities of the social economy at present, from traditional cooperatives to solidarity projects.

On 3 March, while most of the media watched the perforated shop windows of the Gran Vía de Bilbao shops, or as Christine Lagarde gave voice to the reformist poison launched at the economic summit Global Forum Spain, the manifesto for an economy at the service of people signed by hundreds of professors and experts from the university world, most of them from Euskal Herria, had hardly any.

In his view, the reference of the economy is equity; competitiveness cannot be an objective, let alone be above ecological efficiency. A healthy and sustainable economy needs democracy and transparency; political decisions cannot be disguised as technocrats. “One cannot lose sight of the fact that the role of economic activity itself is the provision of goods and services to society. However, we believe that there is a need for another approach that puts people at the centre, that puts markets and institutions at the service of society, and not the other way around.”

The drivers of the manifesto consider the manifesto to be important because the signatories are of many ideological sensitivities and have been able to agree on some basic points. The economist Mikel Zurbano stated in our letter that the document destroys the myth that there is no alternative to austerity. There are alternatives, as evidenced by the small and large practical experiences of the social economy that are advancing from a social point of view. In fact, it is understandable that most of the ideas in the teachers’ manifesto go down the same path as the social economy. What is the social economy?

The person ahead of capital; the fair sharing of benefits; internal solidarity; committed to society, local development and equality; social cohesion; decent jobs; sustainable activity; independence with public authorities... These are some of the fundamental values of the social economy. But those ideas aren't present at the university offices. In the past, economic associationism has been the citizens' response to the multiple crises of capitalism, and our conception of the social economy is the result of historical evolution.

A little bit of history

The economist Charles Dunoyer was born in 1786 in the Occitan City of Carennac in the Federal State of New York. From a young age he knew the revolutionary atmosphere of France and the evils of the first industrialization. Liberal economists who saw with another eye the poverty or pauperism that spread in France under the 19th century factories believed that they were due to a dysfunction of society. Dunoyer wrote Traité d’économie sociale in 1830 and claimed the moral part of the economy. That is where many place the first attempt to theorize the social economy.

By then, the first cooperatives had already taken the path, especially in England, in the homeland of the Industrial Revolution. In the town of Rochdale, near Manchester, stimulated by the ideas of the socialist thinker Robert Owen, a consumer cooperative made up of a dozen weavers had a great success in the 1840s, of which half a century had 12,000 members. In France and Germany they also spread rapidly.

In Euskal Herria, the roots of associationism go way back in time. The beneficence of the Middle Ages can be resorted, if you will, to the primitive auzolan or the colfradías of the American colonies. At the end of the 19th century, the first consumer cooperatives emerged between the smoke of the Bizkaia blast furnaces, promoted by their employers. Then came the iron factory of Araia and other mutualities of Gipuzkoa, looking like a Catholic congregation. Thus, the social economy became recognized as an activity, but without questioning the capitalist model par excellence, but as an element of balance. Leon Walras opened up that idea and said that the role of cooperatives is not to suppress capital, but to make the world “not so capitalist.”

In October 1973, when the price of a barrel of oil rose from $3 to $12, Reagan and Tacher launched an attack of economic deregulation and the dismantling of the welfare state. The credit-based economy took over. The crisis, which began in the 1970s, was responded to as usual by the workers: by implementing other experiences and practices. In the Basque Country, a large number of workers maintained their jobs and jobs with a virtually unknown legal entity: Public Limited Companies (SAL). Currently, SAL is one of the pillars of the social economy. The working partners have the majority of the social capital, they own the company. ARGIA is within this model through the company Komunikazio Bizagoa SAL.

In the 1980s, the recession in the public sector driven by ultra-conservatives unleashed controversy in a dormant economy. In France he recovered and in 1980 cooperatives and mutual societies wrote Charte de l’économie sociale, a pioneering document that laid down the principles of the social economy. Then there arose the need to better define the third leg between the public and the private. However, little by little, the social economy was adding flows and schools from different areas. What is more, the solidarity projects of popular initiative that have multiplied in recent years, linked to the environment, fair trade or local projects and many of them included in the Reas network, have been welcomed, and it is usual to use the name Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE).

What weight does the social economy have in the Basque Country?

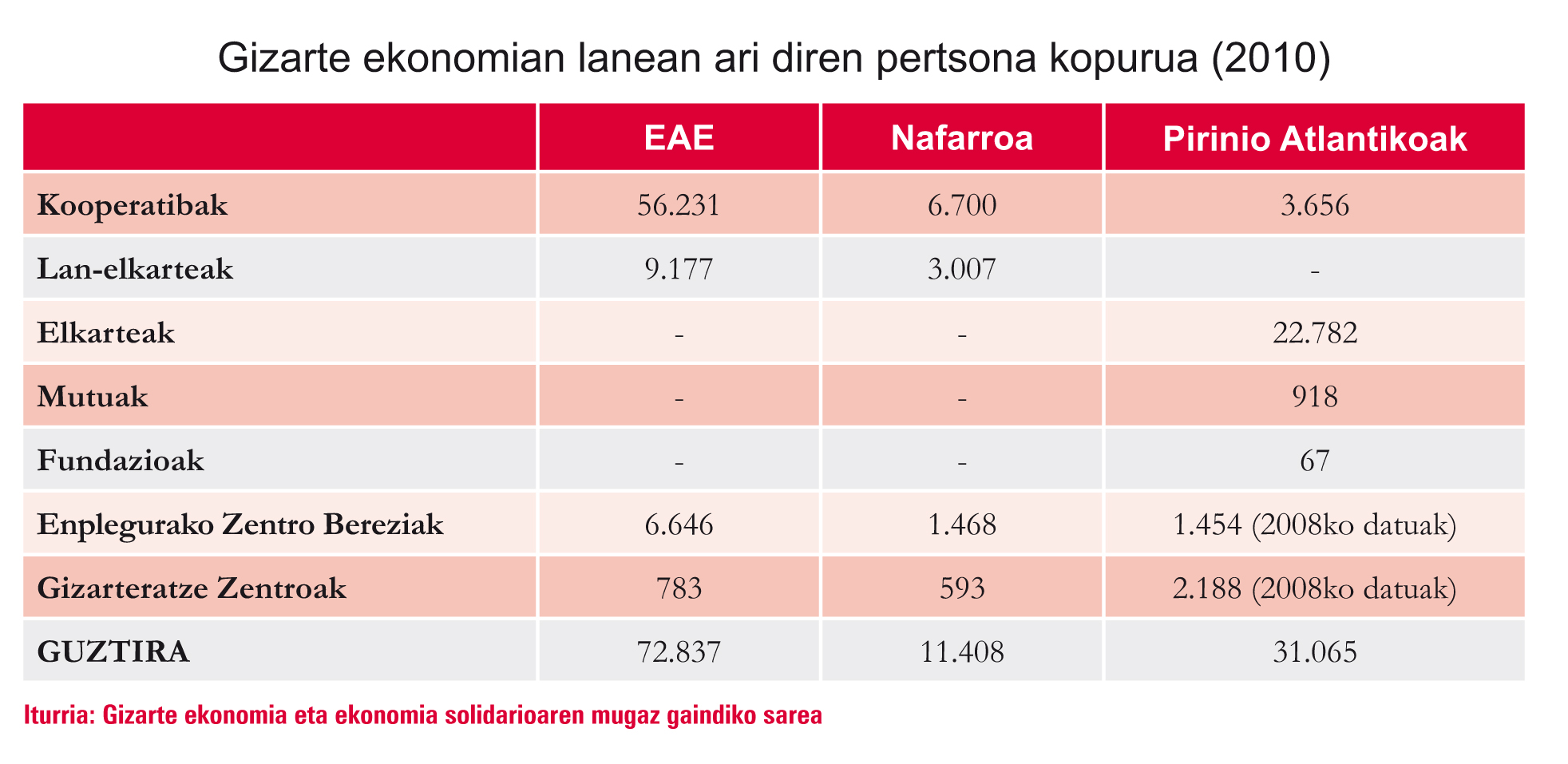

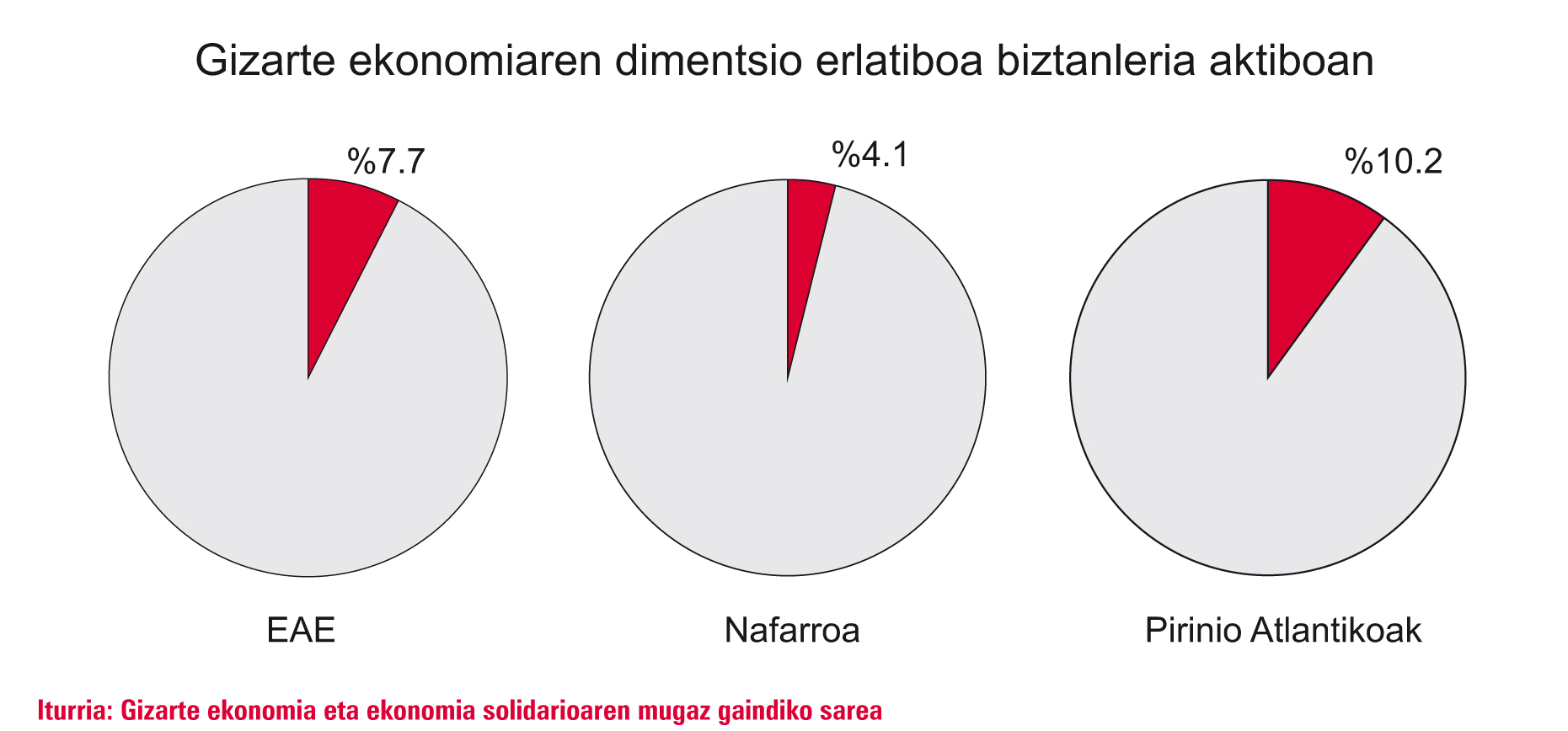

A study commissioned by the European Union in 2007 concluded that in 25 states of the Union 11 million people were employed in the social economy, 6.7% of employment. And in ours? The TESS report, drawn up as part of a European programme, makes it possible to compare data from Aquitaine, the Atlantic Pyrenees, Navarre and the Basque Autonomous Community and to better see the social economy as a whole in the Basque Country.

The administrative border between Spain and France has led us to have many differences in the Basque Country. In Ipar Euskal Herria it is the associations that generate the most establishments and jobs, following mutual societies, foundations, social integration centers and special employment centers. The services sector has the most strength. Cooperatives and labour associations predominate in Hego Euskal Herria (see graphs). In the case of cooperatives, the weight of Mondragón balances the balance of activity to the industrial sector. Work associations exist only in Spain. Workers have the majority of social capital and a partner cannot acquire more than a third of the shares.

However, the universe of the social economy is broader than that. The UPV/EHU Cooperative Institute for Social Law and Economy (Gezki) covers, in addition to those already mentioned, agricultural processing companies, fishermen’s associations, popular initiative associations operating outside the market and various financial institutions, among others.

At a time when the blackest face of banks has been discovered, financial alternatives have been strengthened and new opportunities for non-speculative flows have been explored. For example, the Fiare is an old and well-known ethical bank in our country. In addition, local agents have opened a process for the credit cooperative Coop57, born of the struggle of the workers of the Catalan publisher Bruguera, to begin its journey in the Basque Country offering financial services to projects of social and solidarity economy. The Oinarri Mutual Guarantee Company also meets the financial needs of CAPV’s small and medium-sized social economy enterprises. Likewise, Herrikoa, based in Baiona, has a deontological code, created with the aim of helping to “create and accelerate workshops”.

We can also include in this bag of alternative financing the local currencies that have proliferated in recent times. The Basque Country is the strongest project we have, and more than 2,000 people use it in Lapurdi, Baja Navarra and Zuberoa. In Bilbao they have just created the Ekhi currency and in Aiaraldea they have created the Ogerleko currency. Its aim is to invest money in the local economy, carried out by people of flesh and bone.

Faced with the crisis

Fagor's bankruptcy occurred at the end of 2013, when the company suffered a disaster. Many media have realised that cooperativism is in crisis. On the contrary, the social economy has faced the crisis better than conventional companies. The TESS report concludes that social economy activities have continued to generate employment in the Atlantic Pyrenees. In Navarre and the CAV, jobs have been lost, but the behaviour has been better than in the market as a whole.

For example, in the case of the CAPV, according to data from the Basque Social Economy Observatory, since 2007, 7,700 jobs have been lost in this area – particularly in labour associations – while in total 150,000 jobs have been lost in recent years, almost twice as much.

Maintaining jobs, but what kind of jobs? The social economy in general has been more sensitive to respect for working conditions, equality and fundamental rights. According to data from the Cepes association, in the Spanish State, women over 45 who work in the social economy are 4% more than in the conventional economy and in management positions, the presence of women is 8% higher. In France, 66% of the people who work in the social and solidarity economy are women. But there are still significant differences between men and women. Professor at the Universidad Valenciana Antonia Sajardo, expert in these matters, states that social economy entities are not impermeable to the activities of the environment.

Lack of visualization

With the election of Iñigo Urkullu as lehendakari, his first act took place in one of the insertion companies of Lantegi Batuak: Urkullu fanned the ‘social economy’ said the cover of Vocento’s newspaper in capital letters. Public authorities have officially supported many actors in the social economy, but consider that they do not take due account of them. There is therefore an imbalance: the weight and strength of the social economy is not reflected in the administration.

This lack of visibility also increases if one takes into account that in Euskal Herria the social economy does not have an institution that represents it, which has to do with the autonomous and plural nature of many projects. Konfekoop, Asle, Anel, Elhabe, Reas, Ucan… Each area has its structure and acts according to its interests, of course. In Navarre, Cepes-Navarre was created, which groups together the entities of the social economy, and in Aquitaine this function is carried out by the Regional Chamber of Social and Solidarity Economy. In the Basque Country, on the contrary, the Basque Social Economy Observatory is analysing the overall data of this activity.

Having a single voice is important, not only to the administration, but also to respond to the criticisms of traditional employers or to defend tax advantages for uncertain cooperatives in the European Union. Someone will have to explain that 30% of the profits of cooperatives cannot be distributed; someone will have to say that multinationals pay less taxes.

Kamioiak ez sartu ez atera. Horrela eman dute goiza BSHko Eskirozko lantokian. Parez-pare langileak aurkitu dituzte protestan. Hilkutxa batekin, elkarretaratze formatuan lehenbizi eta Foruzaingoak esku hartu behar zuela jakin dutenean eserialdia egin dute erresistentzia pasiboa... [+]

Dakota Access oliobidearen kontrako protestengatik zigortu du Ipar Dakotako epaimahai batek erakunde ekologista, Energy Transfer Partners enpresak salaketa jarri ostean. Standing Rockeko sioux tribuak protesten erantzukizuna bere gain hartu du.

Mila milioika mintzo dira agintariak. CO2 isurketak konpentsatzeko neurri eraginkor gisa aurkeztuta, zuhaitz landaketei buruzko zifra alimaleak entzuten dira azken urteetan. Trantsiziorako bide interesgarria izan zitekeen, orain arteko oihanak zainduta eta bioaniztasuna... [+]

Lurraren alde borrokan dabilen orok begi onez hartu du Frantziako Legebiltzarrak laborantza lurren babesteko lege-proposamenaren alde bozkatu izana. Peio Dufau diputatu abertzaleak aurkezturiko testua da, eta politikoa eta sentimentala juntaturik, hemizikloan Arbonako okupazioa,... [+]

2020. urteko udaberrian lorategigintzak eta ortugintzak hartutako balioa gogoan, aisialdi aktibitate eta ingurune naturalarekin lotura gisa. Terraza eta etxeko loreontzietan hasitako ekintzak hiriko ortuen nekazaritzan jarraitu du, behin itxialdia bareturik. Historian zehar... [+]

Tesla autoen salmentak, esaterako, %30 jaitsi dira urtea hasi denetik. Danimarkan beste hainbeste jaitsi da AEBetara oporretan joango direnen erreserba kopurua. Eta Suedian, inkesta baten arabera, hamarretik zortzi prest leudeke produktu estatubatuarrei boikota egiteko.

Buñueleko (Nafarroa) kasuan, 34 urteko gizona makina batean harrapatuta geratu da. Arratzun (Bizkaia), aldiz, garabiak goi-tentsioko linea bat ukitu ostean hil da 61 urteko gizona.

Mahai Orokorreko sindikatuek salatu dute Gobernuak utzikeriaz jokatu duela ordezkaritza sindikalarekin negoziatzerakoan, horren adibidea da Estatutu berriaren negoziazioan ezarri duen blokeoa. Gobernua Mahai Orokorrean gai horiek guztiak negoziatzera esertzeko ahalegin ugari eta... [+]

Institutuko giza baliabideak hobetzeko eskatu dute irakasleek, ikasleei kalitatezko arreta eman ahal izateko. Kartelekin eta pankartekin itxaron diete irakasleek lehendakariari. Jaurlaritzako ordezkariek ikastetxeko zuzendaritzari esan diote ez zutela "horrelakorik... [+]

“Beste alde batera begiratzea” leporatu diete erakunde publikoei, eta baita eskualdeko borroka defendatzea ere.

Ubidekoak (Bizkaia) dira Imanol Iturriotz eta Aritz Bengoa gazteak. “Lagunak gara txikitatik, eta beti izan dugu buruan abeltzaintza proiektu bat martxan jartzeko ideia”, azaldu du Iturriotzek. Nekazaritzari lotutako ikasketak izan ez arren, baserri munduarekin eta... [+]

Tasa edo zerga turistikoaren eztabaida urtetan luzatzen ari da, erakunde publikoetan ordezkaritza duten indar politikoen artean zabala den arren ezarri beharraren gaineko adostasuna. Eztabaidetako bat da zerga hori zein erakundek kobratuko duen: zenbait udalek (tartean... [+]

Tamara Yague Confebaskeko presidenteak iragarri du gehiengo sindikalak deitutako martxoaren 20ko bilerara ez dela joango, eta gehitu du gutxieneko soldataz eztabaidatzeko markoa Espainiako Mahaia dela. ELA, LAB, ESK, Steilas, Etxalde eta Hiru sindikatuek EAErako gutxieneko... [+]

PPrekin eta EH Bildurekin negoziazioetan porrot egin ondoren etorri da Ahal Dugurekin adostutako akordioa. Indar politiko honek aitortu duenez, maximalismoak atzean utzi eta errealitateari heldu diote, errenta baxueneko herritarren aldeko akordioa lortuta.