"I'm happy, but not quite."

- In 1936, their father Vicente was shot in Larraga; his sister Marvels was raped and killed. Since then, Josefina Lamberto Yoldi had a cruel life. Despite the recognition granted to him by the Victims Act of 1936, he has a bittersweet feeling, as he has not been able to recover his father's body.

In November 2013, the Parliament of Navarra approved, with the only abstention of UPN, a law in favour of the memory of the victims killed and subjected to repression following the military uprising of 1936. Josefina Lamberto's parliamentary statement comes at 77 years of the outbreak of the 1936 war. Although it has been late for many, the relatives of the 3,400 deaths who suffered the violence at the time have achieved the support they were owed.

He was among those who came to Parliament on the day when Parliament opened the way to law and enthusiastically applauded the decision taken. He had many reasons to feel happy, as he had passed from here to there accusing the family of having lived for a long time. Marvels Lamberto, her sister, was raped and murdered at the age of 14 in Larraga. The satisfaction shown in the act was not total: “I’m happy, but not at all. Now that we have succeeded in passing this law, I can't find my father. Recently, the excavators had been at Ibiriku Yerri, where his father's body had been buried. They searched the estate from the top down, but we couldn't find anything. They say that there they formed a plot and divided the land.”

Lamberto always takes those he had to see as a child in his head: “At two o’clock in the evening they started knocking on the door, threatening to knock it down if they didn’t open it. They went up with crutches and ordered their father to wear his clothes. The bedroom consisted of two rooms, one occupied by their parents and the other by three sisters. By then Marvels was 14 years old and already knew what was going on in the village. ‘I want to see what you have to do to my father!’ he told the aggressors. And they answered him. If it has come! His father entered the village prison and his older sister was promoted to the secretariat. They made the poor man all the wickedness they can imagine. My mother, early in the morning, prepared us for breakfast and asked us to take it to my father and sister. When we arrived there they were no longer there. They were driven to ‘walk’, to fuse them. My father's corpse was buried by a group of neighbors of Ibiriku Yerri and my sister's was found a week later in a sketch with dog bites on the legs. The peasants set him on fire with the gasoline of the separating machine, which was rotting, and killed the dogs.”

Josefina Lamberto lives in the Casa de la Misericordia in Pamplona. She wakes up at 7 in the morning and works for a couple of hours in the laundry of the residence to get some sosas. After breakfast, Paris goes to the social dining room 365 to help you every day. After eating he approaches San Juan de Dios Hospital to spend the afternoon with a young man without family. You're happy: “As amazing as it may seem, I now live happier than ever. Despite the malaria and my torn shoulder, I now feel very happy.”

Larraga in 1936

Larraga was a poor people at the time when her sister was raped and killed: “In Larraga there were four rich, all the others were poor. The men went to the town square to work as day laborers. At the age of 10, Sister Pilar was dedicated to removing weeds from wheat fields. Most of us were farmers. We were poor, yes, but we didn't lack food. We had the pig for the whole year, we had chickens, rabbits...”

The father, affiliated with the UGT trade union, did not attend the Mass. These reasons were enough to decide on his death penalty: “My father wasn’t getting into anything. As a worker, he had signed up for UGT, with no more. We went to Mass and made communion. I still remember the white suit and the black rubber shoes that left me for communion. My father never banned us from going to Mass. And the priests were the clearest and decided to kill one or the other. The rich and the Church shared power.”

A total of 47 people were killed in Larraga, including one armed man. The repression was terrible. Immediately after the shooting of Josefina Lamberto's father and sister, all the property was stolen from the family: “My mother was very shy. From then on I would no longer be the same person. They killed her husband, their daughter, and not only that, they took away everything she had. The mayor put the land in his name and also stole the mare. I remember exactly the little mare we had, big, with its wide hips. The owner of a mare had a treasure. My father left the land and the house as a guarantee to be able to buy that mare. He paid 500 pesetas.”

Lamberto does not want to return to Larraga for a visit. His mother, Paulina Yoldi, stayed alone and was not offered help in the village. Moreover, shortly after the death of her husband and her daughter was imprisoned, after a discussion with the woman of the local baker: “He was in prison for three days, and we were alone at home. No one offered us a piece of bread.”

The mother returned to the house of a soldier who had worked in her youth. His daughters were sent to the house of a man who participated in the violation of Marvels: “When my mother was in jail, she screamed for the window of the cell, which she was drowning. A man named Julio Redín, who participated in the violation of Marvels, called for the woman to be released: Isn’t everything you’ve done to your family enough?” he said, and my mother was free. My sister Pilar took care of Julio's daughter, sick with Down's syndrome, and I was taken to school. I slept alone in the loft, without light. Julio Redín was burned to death in the interior of a truck in front of Fraga, in the city centre. People said it was a punishment of God.”

Pamplona and Karachi

A year later, Paulina Yoldi made the decision to go to the capital. The man, who has been arrested, rented a room in Pamplona, on Javier Aldapan street, with two daughters. At first he asked for alms and soon found work in the Gerendiain store of Estafeta Street, where he sews sacks. He would wake up at 4 a.m. to pick up some money with the bags. “Pilar and I went to the social restaurant that was in the Plaza del Príncipe de Viana to eat and have dinner. We were forced to sing Cara al Sol. All of a sudden, my mother got sick and we got kicked out of the rented room. We had to sleep on the ladder. Because my mother was sick and had to eat something, one day I took a piece of bread in the dining room and hid it in the clothes. Those who were sitting on our own table denounced me to the head of the dining room and agitated me with a stick in my hands. I still cry when I remember all that.”

Lamberto studied at San Francisco Public School. Being the daughter of a rifle, she was not badly welcomed into school. In that grey post-war Pamplona, it gradually became feminized. At the age of 21, following the example of the friends of the crew, he came to a convent, ignoring his mother's opinion: “It was crazy. Some of my friends went to the convent and as I intended to help the kids, so they didn't suffer what I had lived, I went into the nun's house. I was sent by boat to the capital of Pakistan, Karachi. I had a very bad time. The weather was very hard and soon I caught malaria. I still suffer from this disease, it never heals. My shoulders had also torn apart. I was working on the law of a servant. They didn’t teach me English or molten, and because I was poor, the nuns were very cruel to me.”

Paulina Yoldi had not seen her daughter again. Josefina Lamberto spent 14 years in Pakistan and when his mother was about to die he got permission to leave the convent and return to Pamplona/Iruña. Late, but. Through bureaucratic procedures he arrived in Pamplona three days after his mother's death: “I lost my mother’s love to clean the ass to the nuns.”

Shortly after Franco's death, they began to fight with the nuns. Lamberto sought his father and the nuns did not see the search with good eyes. He was told in the convent: “Your father would do something to end up like this,” he said. “And Wonders, what did Marvels do?”

In full confusion, he was destined to Madrid: “I was 19 years old in Madrid. They used me to clean floors. I wanted to be with the poor, but they wanted me slave. In the mid-1980s, General Salas Larrazabal published a list of deaths in wartime, in which Marvels appeared as ‘missing’. I didn't think twice and sent a letter to the Diario de Navarra explaining what happened to my sister, how they raped her, how they killed her ... The nuns got angry and told me that if they were in jail, they wouldn't try to get me out."

At the age of 67, Josefina Lamberto was no longer able to endure any more: “I didn’t care about anything anymore. What was he going to sleep in the street? Well, I would sleep on the street. I had completely lost faith. If you want to give love to those outside, inside the house there must be love, and in the convent there was no love. Thanks to the help of a relative, I was left with a place in the House of Mercy and I came here. Now I live happier than ever, truly.”

More information:

The Berri Txarrak group made the song Marvels about the case.

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

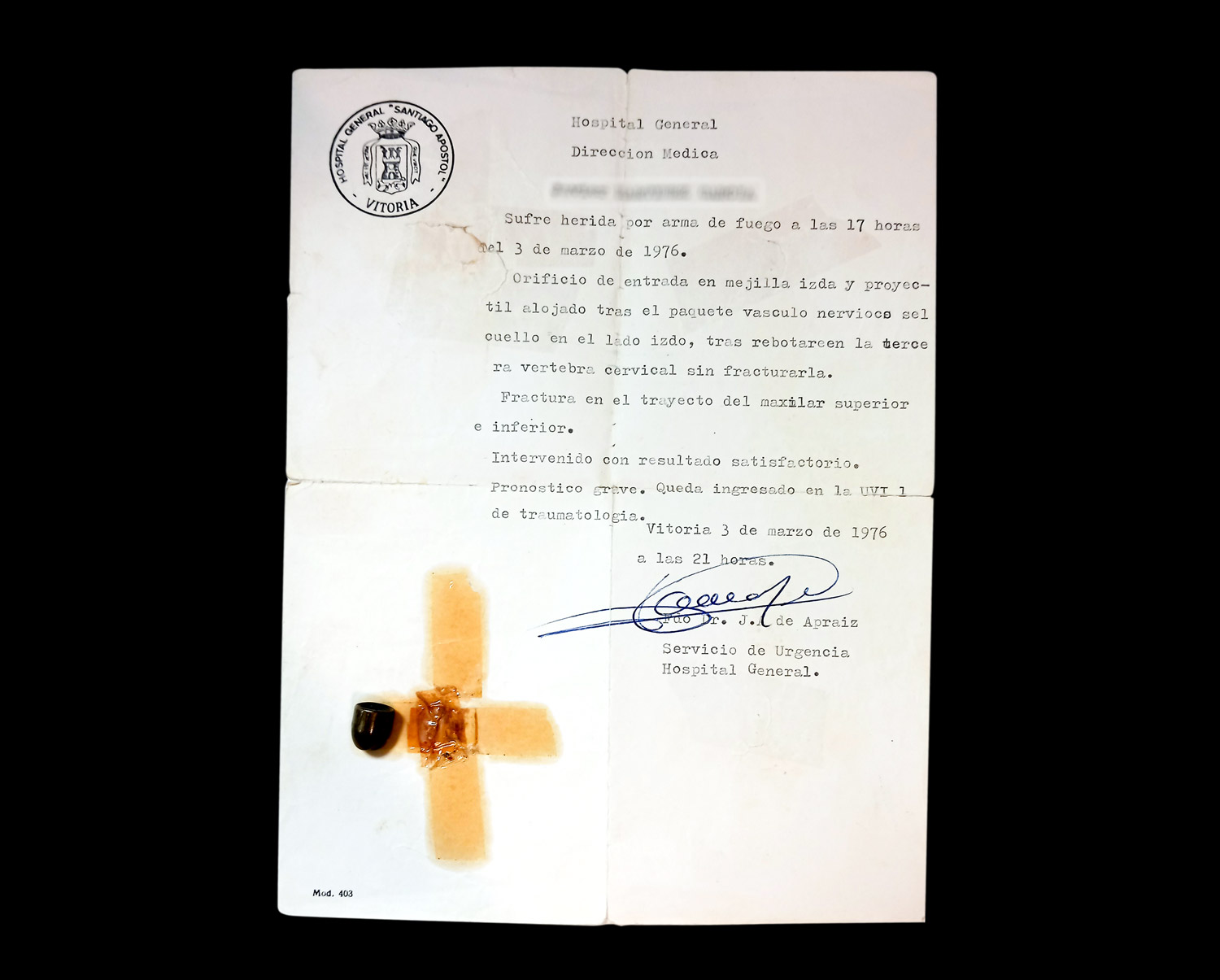

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.