"The documents in the book are the first news about California and its inhabitants"

- Four years ago, the faithful translator surprised us. By then he had brought the Basque to R.L. Stevenson, John Steinbeck, Patricia Highsmith, William Faulkner… and surprisingly, he gave us a great rehearsal job: Basque Country of Far West. Now, for his part, he has done us a job that is his continuation, in itself his first part: Los de California (Pamiela, 2013), as beautiful, as elaborate and delicious as the previous one.

You're a professor, a translator, a writer and an essayist. Four years ago you published Euskal Herria de Far West (Pamiela, 2009). This work gave a different dimension to the work you have done so far. That work made you a writer. The only thing the current Californian does is to confirm it...

But I am still a professor and a translator – as in California, in the Basque Country of Far West, many of the texts are translations – and now, moreover, I also write, yes. However, I see these three works very united. When I have been a professor, my area of work has always been written. I’ve worked writing with the students, with the teachers, who I’ve really worked at IRALE, or reading… My work is always related to written language. For example, when it comes to reading I have made a great effort to offer students interesting, appropriate texts, etc. Of course, the students were the ones who had once stood before me. Now, instead, I have readers, but like the students, I've tried to present interesting and good texts in both books, both in the Basque Country of Far West and in California in this one.

Beautiful stories always as destiny.

Selection work is very important. The newspapers at the base of this book are often heavy. It goes, for example, through the Pacific Northwest Ignacio Arteaga, and in its day to day writes notes about the sea or the time: the length to which they have arrived, the direction by which the wind blows… But it reaches a bay and canoes full of indians approach. The Indians sing the plumiles of a dead bird in the air… Sometimes in a 50-page diary only one or two pages are interested for the current reader, and their selection has been a fundamental part of the work.

He has had to try to sew them together to bring these interesting texts together. California's aren't just a good text anthology.

I wanted to complete the narrative, not the textual anthology. If I had completed textual anthology, I wouldn't have seen the evolution of history. If the same texts are integrated into a narrative, the result is different. In my opinion, in this case, the order that sets the chronology was necessary. Also place the facts in its historical context.

“In this case,” he says. Not in the Basque Country of Far West?

Maybe not so much. Because in that case the time was better known to us, the reality as well. We all know, more or less, the Basque pastor of that distant West. In this case, what do we know about 16th-century or 17th-century California? ... Few things. It was therefore necessary to place the texts in time and to explain the context in one way or another.

You were in Nevada the 2007-2008 course and collected different materials in the time you were, with the cure of the Basque Country in the West. Instead, here we have taught you in the time when you’ve worked on the compilation of California texts…

When I did Far West, I was at the CBS in Reno, at the Basque Study Center. I recorded the files and the library. When I went to Reno, I also remembered that work. I intended to do so. This second work has another origin. We did a stay in California in 2010, in Stanford, and although I had no intention of working, I didn't hesitate to guess. On the one hand, on the other, Basque names appeared in the corners. The truth is that the first Euskaldunes names entered the house through the second daughter. He was then about nine years old, and when he started going to school, he brought home work. It was a social science subject, and it was about the history of California. Standing next to her daughter, helping her in her studies, they talked about people or historical characters who were of great importance in creating California. The first, Hernán Cortés – and I have heard it, of course – and, among others, a certain Sebastián Vizcaíno. "That was going to be Basque! I said to myself. Next to him was Fermin Lasuen. “Look at another one!” My daughter wanted to correct me. “It’s not Lasuen, it’s Lausen. This is what the professor tells us.” I say no, he needed a Basque. It was Lasuen, and not Lausen, although our daughter's teachers pronounced it like this. I started looking for those names.

How did you focus your curiosity?

I started reading history books, and soon I realized there were many Euskaldunes names. Stack! Governors and others. Arrillaga, Borika, Oñate, Anza… And I started writing about them. However, I didn't want to rely on historiography, I wanted original documents, if possible, and I started searching. It was also pretty. In fact, the colonial administration had ordered the first explorers and navigators to make known exactly what they saw, reports and other details. Soon I read the newspapers of Sebastián Vizcaíno, of Juan Bautista Anza, of José Joaquín Arrillaga… Then I began to tell myself that there was a reality that was completely unknown to us. When I started looking for documents, it seemed to me that I was doing archaeology: the work of bringing to the surface the reality that was hidden. Other times, not as an archaeologist, I've had to do as a detective. “Where can the newspaper written by the Biscayan friar José María Zalvidea be?”, I, which was referred to in the works of historian Hubert Howe Bancroft. “Where is the day to day?” He writes to Santa Barbara, to the archive of Franciscan missions, and there, no. “It may be in this place.” And on one side, on the other -- Zalvidea's day-to-day original, for example, I found it in Berkeley, in the Bancroft library. There is also the day to day of the Arrillaga expedition to the land of the yums of Colorado. My job has been to find originals in the effort. In some cases, I have only found the text in English, but most of the time I have managed to reach the original document.

And once you get the originals?

Well, read it patiently. And of passages, without quaint texts, he chooses the most important texts, which could be the most significant, in the thread of the main narrative. While I was in California, I got a number of documents. After my stay here I have exercised myself in the path of the archive. I've learned a lot along the way! Archivo General de Indias, located in Sevilla (Spain). Online material! You can be at Zalduondo and, at the same time, read live the letter written by the Basque friar in the 17th century!... Little by little, I was completing the California painting.

“Little by little”…

What has cost me the most is to merge the texts. I wanted the reader to read this book as a narrative. To do so, he had to make ties, from one side to the other, without making a leap. This narrative has been the hardest. On the other hand, I have always sought legibility. I think the issue is interesting to the Basque, that the Basques who participated in the exploration and colonization of California must be in our historical memory. It is therefore my duty to present it in an attractive way. I've made a huge effort in that, in the narrative, in making a clear text that reads well. I think it had an obligation, and that doesn't come out on its own, either in the first, or in the second, or in the third. Rewriting is a long, ongoing work.

Most of the texts you have brought to us in the Basque country. Some, leave them in old Spanish. What was your point?

Sometimes it seemed to me that some passages, such as some passages from the letters of the Franciscan Fermín Lasuen, were wonderful. The translations I could do were not helpful, they were so well written! The opposite: translating them into the current standard language, would make them vulgar. Most of the texts I have brought to the Basque Country, yes, but sometimes it seemed to me that the language itself, that Spanish of the time, bore the mark of time, helped to place the facts, and I thought it appropriate to leave those texts as they stand.

We've already said it a moment ago, Far West -- first, then California, but this second one came out of the loop.

Far West -- when I was writing, I didn't know anything, I would write this. For me, the story of the discovery of California has been a discovery! I knew more or less the reality of the Far West. The one in California, on the other hand, has happened to me something new: I did not expect that in the creation of California, so many Basques would be able to participate and, in addition, have that leading role.

When you were at Stanford three years ago, what did you know about the Basques that were in California?

I had nothing but news of the day. The book, in this sense, has happened to me a learning process.

These are tremendous, fornid, well-charged jobs. Big companies, I mean ...

I think I do them because I'm unconscious. When I start working, I don't realize where I'm getting in. If I knew that, I don't know if I would get on my way in this kind of work. In the last four years, I have done little else. I'm a full-time professor, and I haven't had any liberations to do this work... But he's interested in it, interests it, arouses curiosity and continues. One data leads to another, others, they are related… and so on.

You say you're unconscious, but I don't know what you mean: unconscious or sleepy? Because you are a insomne...

Yes, ha, ha, ha… Both unconscious and insomne. That also gets me to work. However, I feel happy as I do. It's over, if not!

Reading Californians, we can not only realize the history of Euskal Herria, but also of California…

That's right. The title would also want to make that game. Who is the book? About the Basques of California, yes, but also about the Basques of California. At the beginning of the book, California is a hole in the maps of the time and in the maps of the later time. In the book we see how the maps of California are shaped and shaped from the eyes of the Basques who went there. For example, through those explorers, friars, Basque sailors, we can see what California was. Californians are therefore Basques, but also their first inhabitants. I think the material I've used is of great interest, as it's the first news about California and its people. There is nothing before these writings. The anthropologist and the rest, when they want to know that first California, have to inevitably resort to the documents that I have used. They are testimonies of the first relationship between Europeans and Indians. Since the middle of the 19th century, documents have been much more numerous, including those that provide a view of the Indians. But by then many of the indigenous nations mentioned in this book had already disappeared and the lives of those who survived were contaminated.

Joseba Sarrionandiaren hitzak, Kaliforniakoak liburuaren atarikoan

“Asun Garikanok xehetasunez kontatuko du liburu honetan euskaldunek penintsula hura eta handik gorako dena kristautzen, espainiartzen eta kolonizatzen egin zuten ahalegina. Monarkia espainola, indioen kontra, Kaliforniako itsasertza menperatzen ahalegindu zen hiru mendez. Haustura geologikoen moduko borrokak heldu ziren gero: Mexikoko independentzia gerrarekin, 1810-1820, Kalifornia Mexiko bihurtu zen, eta Mexikoren eta Estatu Batuen arteko gerrarekin, 1846-1848, gehiena Estatu Batuen barrutira pasatu zen (…) Liburu honek Far Westeko Euskal Herrira eramango gaituela barrundatzen dut, honen amaierako puntuak hura berrirakurtzea eskatuko baitu. Bi liburuek erakusten dute gizajendearen historia zer gogorra eta arraroa izan den (…) Kalifornia Euskal Herriaren probintzia bat dela erakusten da Asunen bi liburu hauetan, eta onartu beharrekoa da, are gehiago kontuan hartzen badugu Euskal Herria Estatu Batuen partea dela aspalditik”.

“Ibilaldia hastean oso bide txarreko paraje bat igo behar izan genuen: gero ordoki batzuetara atera ginen, eta handik bi legoara Talihuilimit rancheria aurkitu genuen. Hiru andre adineko bataiatu nituen han: lehenengoa hirurogei urtekoa, hanka batetik ezinduta zegoena; Maria Magdalena jarri nion izena: andre honek seme bat du Santa Inesen: bigarrenak 65en bat urte izango ditu, eta gerrian hartz batek hozka eginda dago: Maria Marta jarri nion izena. Seme kristau bat dauka La Purisiman: bataiatu nuen hirugarrenak ehun urtetik gora izango zituen eta Maria Francisca jarri nion izena (…) Aipatutako ranchitoan bost andre zahar eta agure bat bataiatu nituen: lehenengo andreari Maria Lucia jarri nion izena; bigarrenari, Lucia Maria; hirugarrenari Maria Dominga; laugarrenari, Dominga Maria; bosgarrenari, Fernanda, eta agureari Fernando”.

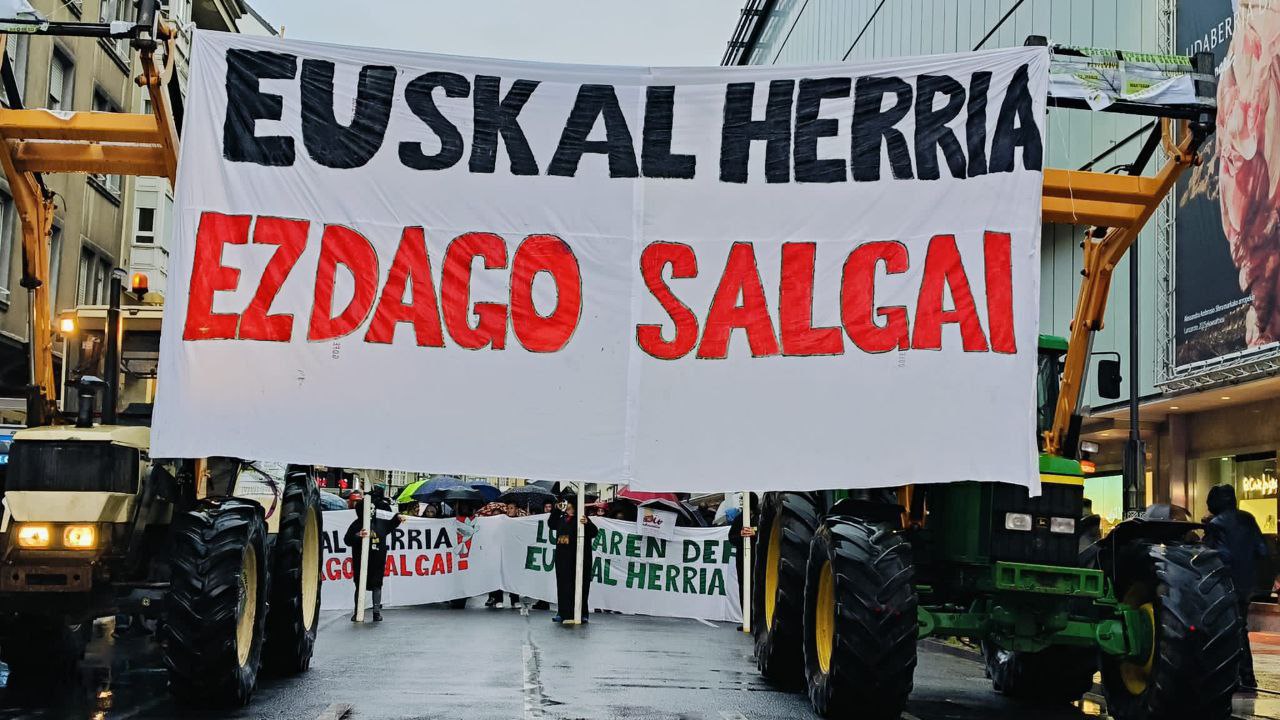

BRN + Neighborhood and Sain Mountain + Odei + Monsieur le crepe and Muxker

What: The harvest party.

When: May 2nd.

In which: In the Bilborock Room.

---------------------------------------------------------

The seeds sown need water, light and time to germinate. Nature has... [+]