What did the opposition say about the murder of Carrero Blanco?

- Carrero Blanco was killed by ETA on 20 December 1973 in Madrid. For the apparatus of the dictatorship and for the bourgeoisie it was an unexpected blow the death of the one considered descendant of Franco. The anti-Francoist opposition expressed its opinion on this attack. Some were critical, while others expressed “irresistible joy.”

40 years ago, ETA murdered one of the loyal collaborators of Franco, Luis Carrero Blanco, who was killed by eta. He was, along with the dictator, the military man who had been in command for the most years since 1940.

On the occasion of the change of government of June 1973, Franco appointed him head of government and a week later he had to face the general strike of Navarra. In addition to daily activities, his most outstanding task was to maintain the post-Franco dictatorship through the operation in favor of Juan Carlos Borbón. After the disappearance of the Caudillo, Luis Carrero would be the regime’s new vertex to launch and consolidate the “July 18 monarchy”.

The admiral of Santoña, as a military like Franco, was above all the subsectors that were supported by that dictatorship, but at the same time, although he was close, he had not been linked to a specific political area. He was able to join the extreme blue sectors of the regime and, at the same time, help the old and new technocrats of Opus Dei. It was therefore an incomparable need to maintain the political-ideological axis of the Franco regime without Franco.

But all this was sent to heaven by the attack on her. On 20 December 1973, the spectacular attack by the ETA group “Txikia” in the heart of Madrid surprised the apparatus of the dictatorship and the agents of the Spanish bourgeoisie.

Since 1970, the crisis in the regime has become increasingly apparent. The strikes of the workers, the mobilizations of the students, the removal from the dictatorship of certain sectors – many groups in the Church and some democrats who were in the allegation –… This attack was a major component: Franco no longer had a relief. The bourgeoisie, for decades joyful in power, was suddenly filled with a void that I did not expect.

This bewilderment was no less in the opposition institutions. The first signs of the economic crisis and the demands of the workers heralded a hot winter. In addition, several trials that were about to start, mainly against the leadership of CCOO, called “1001”, attracted the attention and efforts of the leftist groups. But the outbreak of the early morning of 20 December put all this aside; in addition to bringing the succession of Franco to political debate, everyone was talking about that attack and its armed activity. After overcoming the initial disbelief, the exiles, as well as those who were in hiding within the State, showed very different positions and opinions regarding the assassination of Carrero Blanco.

As soon as the attack is known, a number of senior leaders stated that it was impossible for an organisation such as ETA to organise such events. The lehendakari of the Basque Government, Jesús María Leizaola, for example, described as "false" the statement of claim that ETA issued at the time. When the representative of this institution came to tell him that they had done so, he had to recognize that the author was ETA and, incidentally, he stressed that it was an institution that had no relationship with the Basque Government.

The members of the Spanish Communist Party were more committed to denying authorship and criticising. Using the famous Communist newspaper L’Humanité, which was printed in Paris, the authorship of ETA was questioned, both direct and indirect. After recognizing that the crisis of the dictatorial regime had begun with the death of Carrero, they said: “The circumstances of Carrero Blanco’s death are very surprising… The explanations that have been given so far are obscure and dignified… It is not yet known what the hand has decided the murder. In any case, these are ex-officio, well-educated people, who do not seem to be the work of those ‘amateurs’ who have slightly confessed to the attack. By doing so, they hide the true authors.”

At a press conference in the Basque Country and in Bordeaux, ETA announced more precisely the authorship of the attack. However, the EPK criticized in the journal Euzkadi Obrera, stating and reaffirming that “there were many dark and suspicious aspects around the explosion in Madrid” and that it was necessary to “verify which are the authors and, above all, the stimulators of the action”. After all, according to the Communist Party, this attack had nothing to do with the interests of Euskal Herria, since under the pretext of the attack repression increased.

The action was also criticised by some extreme left-wing groups, although to a lesser extent. The ORT, deeply rooted in several districts of Navarre and Gipuzkoa, criticized in its publication En Uso on the day when “judgment 1001” was to begin the attack. These Maoists opposed the “sterile way of violence” being developed by ETA, revolutionary violence by the actions of the masses, and after recognizing that they had no possibility of influencing the decisions that ETA could take, proposed the following reflection: “However, we have the right to demand that ETA(V) take the most appropriate dates to carry out its actions.”

And the other ones?

Other institutions were far from these humble criticisms. On the contrary, many gave virtually all their support to the action of ETA(V), including LCR-ETA (VI). For the establishment of this organization, both LCR and ETA(VI) Troskists had just gathered in Spain, and the latter, as we know, had shared militancy and desire for many years with ETA. On the occasion of the 6th Assembly, there was division and debate in its magazines (News and Zutik) offered many debates, reflections on the question of nationalism, as well as on the armed struggle, in particular by criticizing ETA’s militaristic activity. But this time they were in favour of the attack on Carrero. In Long, they said: “And VI-LCR clearly supports the murder of killer Carrero, responding to the death of six fighters in recent years, and understanding that ETA V’s retaliation is prudent and correct” (sic).

In addition, in the publication of the journal Lucha, which was published at the level of the Spanish State, a statement was published by the political leader of the organization in support of the action: “Given the encouragement of Carrero’s murder to mobilize the masses and the objective consequences of his disappearance within the ruling class, we believe that the consequences of the attack are positive. That is why our support for this action is total.”

Since the 1970 Assembly, the ETA (VI) were engaged in abandoning activism and integrating into the labor movement, but with these statements they seemed to have returned to the ideas of before. The Troskists said that Mas and the working class had to use weapons to make the revolution, but they were not very clear how to get to this situation, nor how to reconcile the ETA attacks with their political demands: the need to “awaken enthusiasm” and “anticipate the actions” of those masses to take the weapons.

Contrary to the contradictions, the then Trojan leaders supported the 1973 attack, precisely by some of those who years later have harshly criticised ETA.

Justification of the context

Many parties and institutions were cryptic but uncritical of the attack. At the end of 1973, Carlism dedicated the entire magazine “to revolutionary violence”, not to mention the attack. For its part, the UGT trade union wrote for a long time in its main publication in exile to bring to light the murder of Carrero: “The attack on Carrero Blanco must necessarily be framed in the context of the division and hatred that the regime has wanted to maintain since the civil war, not forgetting that the fallen man was appointed by the tyrant to keep the tyranny beyond his death. Only in this way can this fact be measured and judged by everyone according to their own convictions. But in the universal consciousness it is easy to notice that there has been total understanding.”

40 years later, the context to which UGT referred has changed substantially, conditioning the political and historical analyses carried out from the current perspective. But, in fact, these were the positions and opinions of some political actors at the time. When it comes to making a complete history, it is also necessary to explain those who cannot be politically correct in order, among other things, to better understand the follow-up and diversion of armed actions.

Bilbo, 1954. Hiriko Alfer eta Gaizkileen Auzitegia homosexualen aurka jazartzen hasi zen, erregimen frankistak izen bereko legea (Ley de Vagos y Maleantes, 1933) espresuki horretarako egokitu ondoren. Frankismoak homosexualen aurka egiten zuen lehenago ere, eta 1970ean legea... [+]

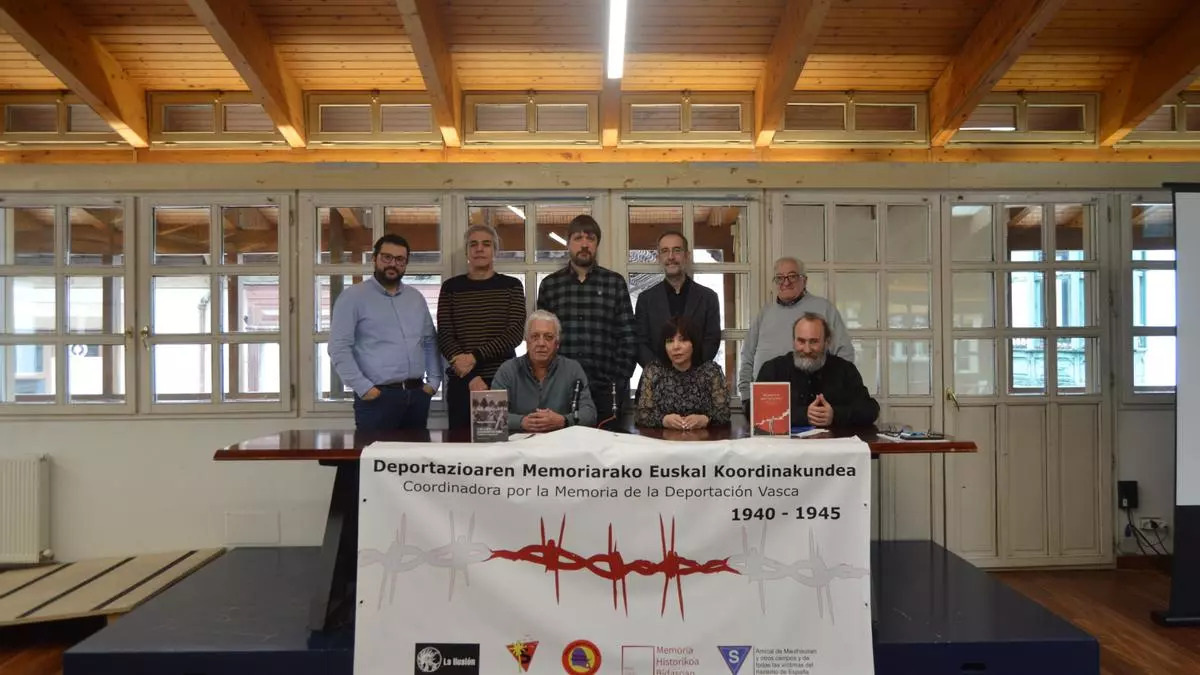

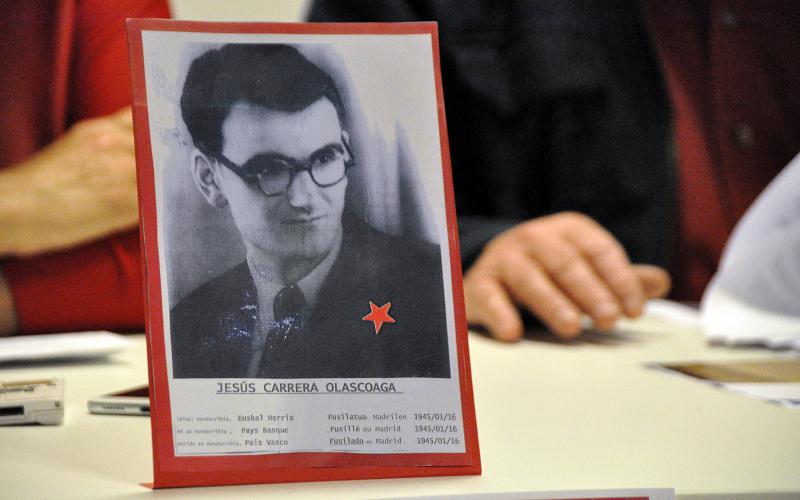

Deportazioaren Memoriarako Euskal Koordinakundeak aintzat hartu nahi ditu Hego Euskal Herrian jaio eta bizi ziren, eta 1940tik 1945era Bigarren Mundu Gerra zela eta deportazioa pairatu zuten herritarrak. Anton Gandarias Lekuona izango da haren lehendakaria, 1945ean naziek... [+]

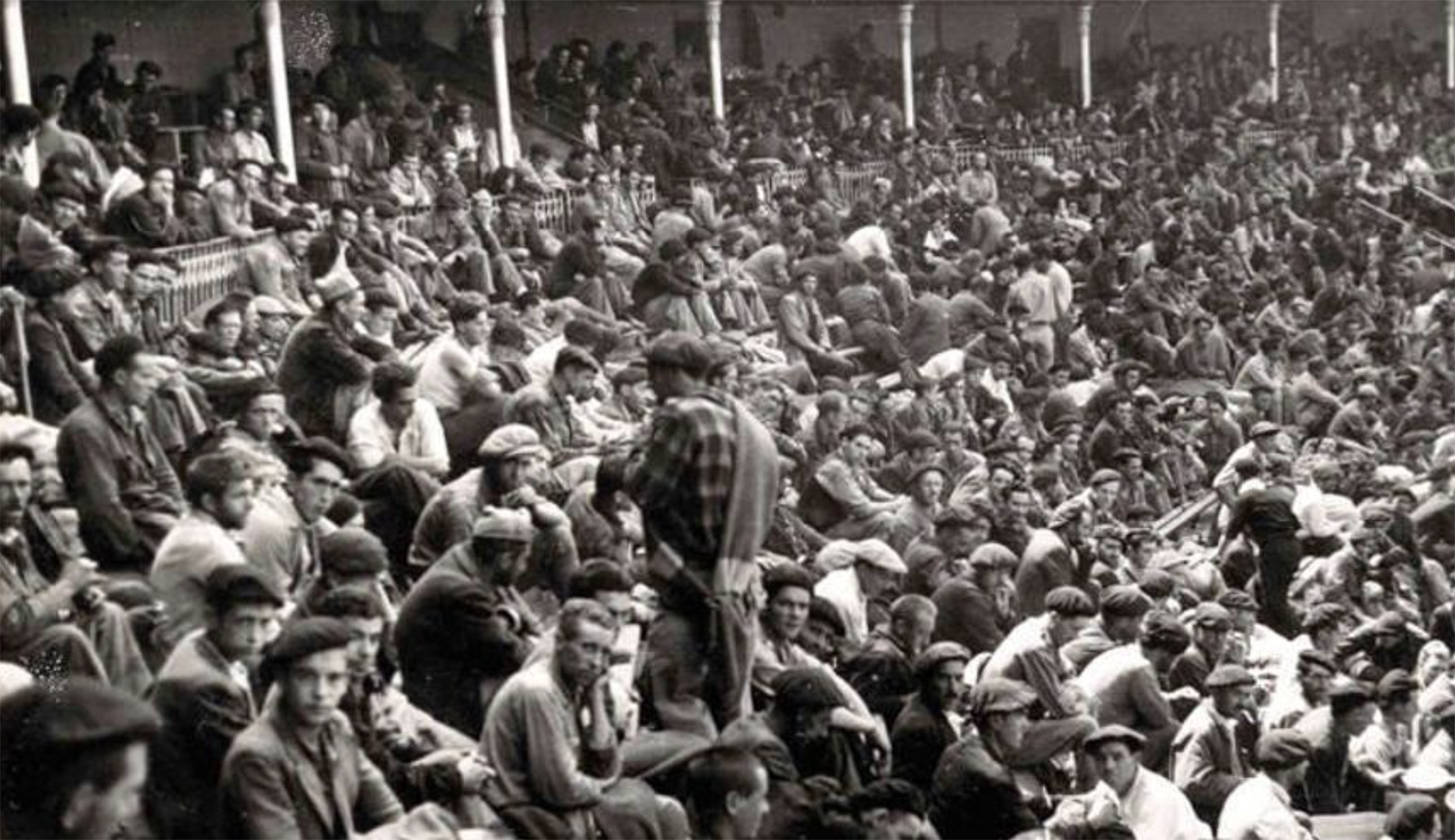

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]