The anarchist was always on the border

- On the sixteenth anniversary of the death of the Donostian cenetist Manuel Chiapuso, we have recovered eleven details of his life and have revisited his extensive libertarian trajectory through the family.

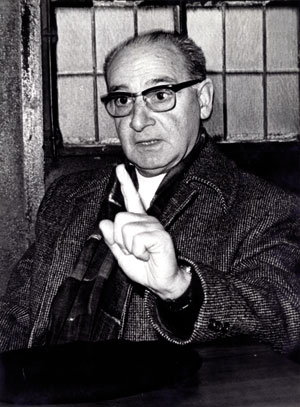

“Although there are modern theories that are interested in long, falsified or overtaken explanations by future generations, and that mock the small story, the small story is constantly intervening and, in many cases, even concretized.” The words of the writer Fred Bérence were collected by the revolutionary Manuel Chiapuso and put in the beginning of the book The Anarchists and the War in the Basque Country. As an epitaph of his life, these are words that perfectly describe this report; for those of us who work in the field of historical memory, we have words that perfectly sum up our mission.

Since his little story, Manuel Chiapuso’s works have strongly influenced, and his speeches have shaken the society of the time. The young man died at Cruces Hospital (Bizkaia) on 29 November 1997. A long struggle for freedom that has left us a dozen books and a lot of articles from their ideas and facts.

“He was a very sensitive, educated, intellectually capable speaker and fine speaker. Also in his ideological approach it was very radical: it was always moving within the limits of legality and illegality… I was really surprised! My family has been political, but Manuel always went further. He spoke very well, but he was always on the edge; he was the vanguard until his death,” says his niece Norka Chiapusso (Donostia, 1963), a theater programmer at Donostia Kultura. “I was a brilliant person: critical, but friendly, loving, sentimental, intellectual… All I tell you is little,” adds Lucía Cantabrana (San Sebastián, 1940), wife of the cousin of Manuel Chiapuso and mother of Nora.

The 1970s: the revolutionary return

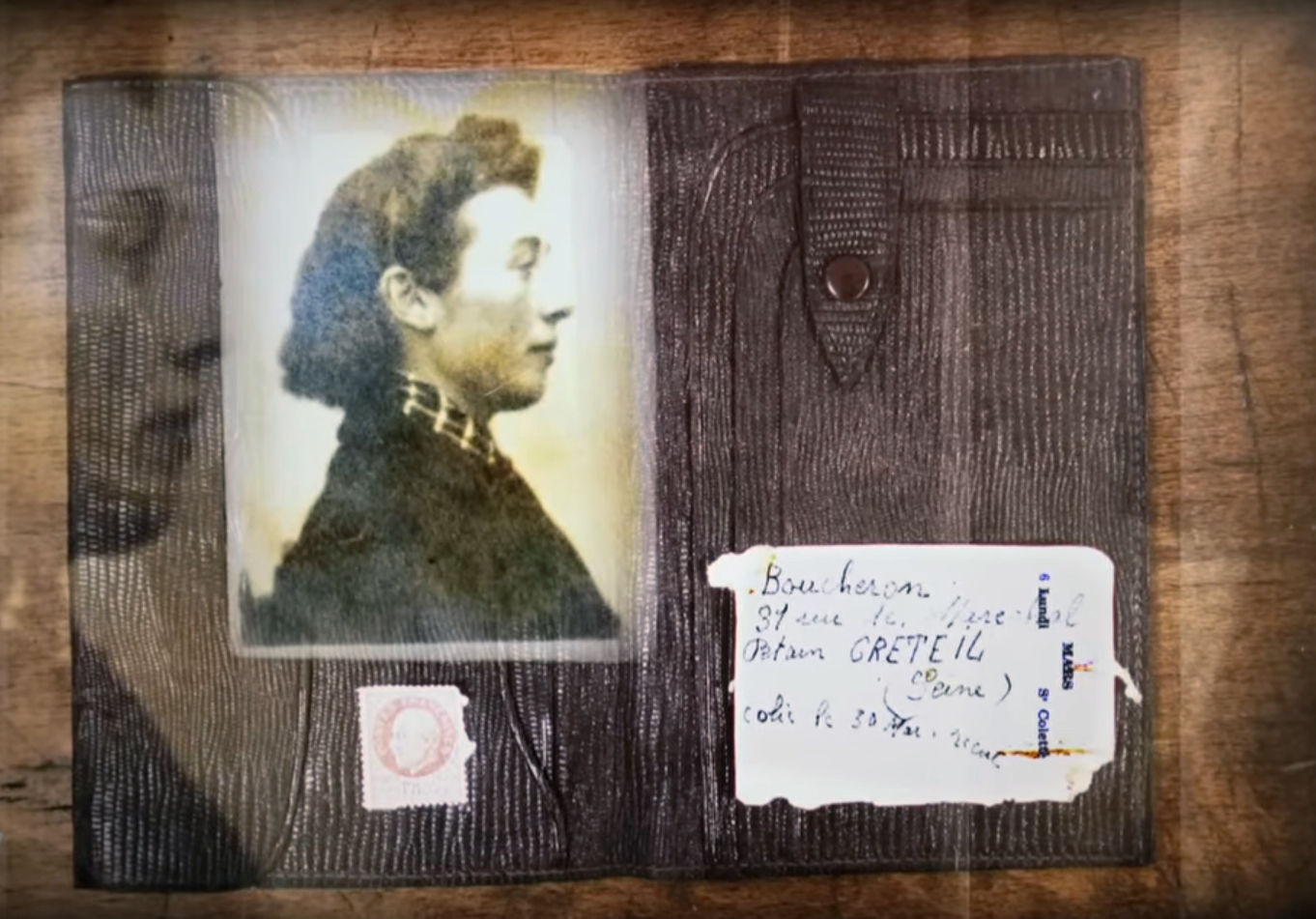

During the decades he lived in Paris during Francoism, he had a diffuse revolutionary activity. But in 1972 or 1973 he resumed the struggle and began to cross the clandestine border with his brother Ignacio, in order to help his anarchist friends of Gipuzkoa and Álava. At first, these trips were used to make visits to their relatives.

“They always came on Christmas day, he and his brother Ignacio, and they drank coffee and champagne. The conversation was very enriching, always with its themes: anarchism, politics, past… In summer we also had the two brothers many nights among us, and we went to Gabiria,” explains Cantabrana.

Casilda Hernáez, the anarchist militia Casilda, appeared with them for many years. Casilda and her husband, the historic anarchist anarchist Félix Likiniano, lived with Manuel in the same house in Biarritz: “Since Likinian’s death, Casilda had come many times with the Chiapuso brothers,” Lucia explains. It seemed like Agustina de Aragón, very wrestling, always with the txapela in the head, very masculine for that time.”

Martinez, who was captain of the Republican Army Aviation, also accompanied them on his visit. They called him a taxi driver. “Joe, what movement did he have too! Manuel loved it! They were intimate friends.”

Of Italian origin

Manuel Chiapuso's grandfather came from Italy to San Sebastian to make the North Railway and married a woman from Aiete. Except for a ‘s’ that changed his last name for several reasons, they have kept it until a year ago: “I have changed it with my children and my sister, recovering the real last name. Now, reading the original you understand where we came from,” Chiapusso said.

Born on April 14, 1912, on the day of the Spanish Republic, his parents exiled in Paris, the young Chiapuso grew up in the valley of Zubieta, in a hamlet of Urnieta, in Basque. At 13, she refused to attend the seminar and started working. At that time he formed a group of theatre enthusiasts. At the age of 19, she joined the CNT trade union and was founded by the Young Libertarian of Gipuzkoa, of which she was the first secretary.

They started a relationship with a woman and had their child together, but “the relationship didn’t advance,” says Chiapusso. Afterwards, she had María, the Aragonese anarchist to whom the last name is unknown, until she murdered her.

All life in struggle

In the 1930s, Manuel participated in demonstrations and calls for workers' movements. He met several prisons, including Ondarreta, Alcalá, Ocaña and San Miguel de los Reyes, among others. When the war broke out in 1936, he was in the front line organizing the defense of San Sebastian, as well as attacking the Loiola barracks. It also participated in other activities during the decisive months: Aia, San Marcial, Irun and Puntza. He was appointed Vice-President of the Working Section of the Defense Board of Gipuzkoa and Chairman of the CNT of Donostia-San Sebastián.

On September 13, 1936, when the Francoists conquered the Gipuzkoan capital, Manuel fled to Durango, wounded by the soldiers’ shots. From there to Bilbao. There he worked as the propaganda officer, doing a great job: He founded the journal Horizontes and the journal CNT del Norte. His intention was to introduce the CNT into the government of lehendakari Aguirre, with whom he met in 1937, but in the end he was unable to do so.

When Bizkaia fell into the hands of the franchisees, Chiapuso went to Barcelona, where he served, among other functions, as anarchist delegate to the Ministry of Labor. When Catalonia was about to fall, it escaped to France and was in several concentration camps. He later joined the Resistance until he bought his home in Biarritz in 1944. “There was always a place for the anti-francoist and leftist. They ate with Casilda. They were very generous,” the relatives remember.

When the Nazis left he dedicated himself to reorganizing the CNT, helping the exiles, he was a member of the Basque Consultative Council… So he spent a few years, until he finally went to a hamlet on the outskirts of Paris. “They were surrounded by animals, they were very sentimental,” said Cantabrana. He studied at Sorbonne in 1949 and was a professor of language and literature.

The appearance of the missing brother

His brother Josetxo Chiapuso spent the war deactivating the diving pains. But once there was an explosion at sea and it disappeared. In any case, neither Manuel nor Ignacio ever believed that his brother died, they were convinced that he was not there when the explosion occurred. “For years they searched for his brother, Ignacio also traveled to Russia,” explains his nephew.

“They didn’t find it and Ignacio died forty years later, one day in the 1980s, Cantabrana received a phone call from press officer Mari Pepa Sanz from the City Hall of San Sebastian: “Do you know Joseph Chiapuso?” And since I've always heard his name, I said yes. ‘Paris is between the Basque Country and Paris, in a village in southern France’, was the answer.

Manuel rushed to his missing brother, but Josetxo had already lost his head and only thought of his father and San Sebastian. “I was in a psychiatric hospital. Because they needed some birth data, they found us calling all the Chiapuses of Donostia. Manuel went continuously to visit his brother, who was very sorry for Ignacio's death without having seen him. After six months Josetxo died and never knew his circumstances…”.

Conferences to conferences to death

“Euskadi harmed them, they lived in the Basque Country. Although they were anarchists and internationalists, they were in the heart of the Basque Country, they did not lose that reference,” says Chiapusso. In recent years, Manuel participated in many conferences and political events in Euskal Herria, with his friend Martínez, “taxi driver”.

When he died in 1997 he was incinerated in the cemetery of Derio, with the help of 20 or 25 anarchists. There was Norka Chiapusso, with his late father: “It was exciting. Anarchist people gathered together, younger people, it was a simple but nice act.”

The words of Lucía Catanbrana, Ignacio, Martínez and Casilda himself, who were in those conversations of Manuel Chiapuso and San Sebastián, are perfectly described: "They were idealistic, they had clear political goals. They did bring their ideas to the end!”

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

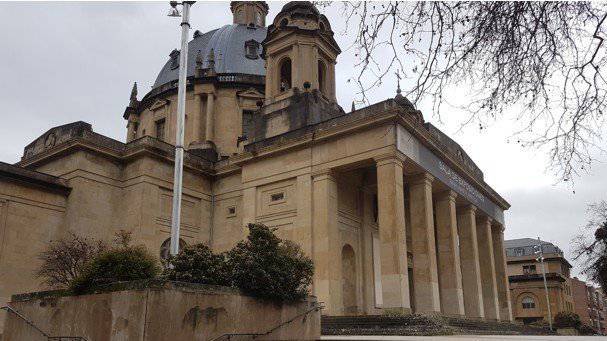

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

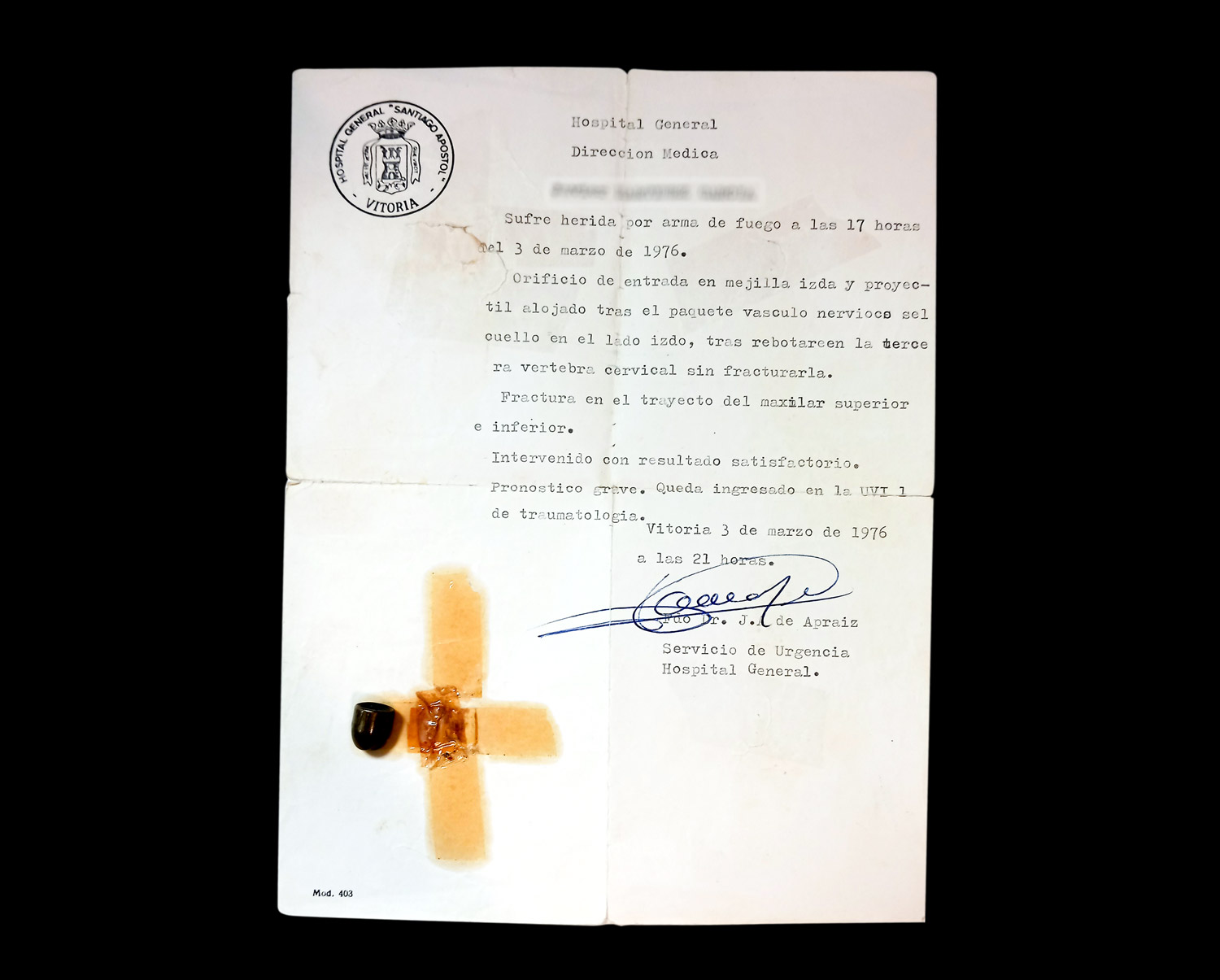

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.