"I have to give back to society everything I've received in this life."

- Fifty years ago he acquired religious life. It's the Carmelite of Vedruna. From a very young age he works in feminism, in the transformation of the Church, in a better world. He is happy, he says he has achieved many of his goals.

Fifty years of carmelites.

I was born in 1944 in Arakaldo. I'm 68, in December of 69. I was 18 years old when I chose religious life.

Religious life and street life: feminism, new Church, commitment…

I'm not the only one. There are many who work on it. But, of course, it tells us “religious” and the image of the habit comes to us. In any case, there are many women who work on it. It's true that we don't carry any cards to prove it, but the married woman, or single woman, doesn't wear it, and yet, they're working in several areas. On the other hand, we have to revisit that image of religious life: habit. Jesus himself, who was walking down the roads of Nazareth, was walking alone. Nobody would approach, cure, touch this, that... I didn't pay the least attention. Then there's the fame, not the fame of the beginning. Many men and women work for a better world and thanks to these millions of gestures this world, which is quite bad, is not broken.

You were 18 years old when you chose the option. Seven years later you vowed forever, at a time when the habit reigned among the religious.

At first I also went for a walk. But we were seventeen women, very wrestling, the ones we saw that the world was changing and the ones we saw that religious life had to change. We got the habit, yes, but with the total intent of undressing ourselves. Seventeen women have been in contact with us after fifty years! Some left that life, they were years after the Council, hard times, conflicting years… I studied in Bilbao, at the Carmelite College of Barreinkua. In 1973, I made the last vows, and the woman was already discovering new worlds. It was May of 68, and that also influenced us. I lived in the convent of the Carmelites of Vitoria at that time, and the news of each other came to us. Among them, the May of Paris, the Burgos process, the beginnings of ETA…

Did you all receive this news equally, or were some nuns more sensitive than others?

All the same, never. Never. Consciousness is a very personal thing. Is that not the way the current Pope says? “Think about your conscience.” There are people who never know. Others, instead, run faster. I might be one of them: I ran faster, but there were already many running, running the marathon. In the group of seventeen, we were about ten or twelve faster. It wasn't just me. We had ideas, intentions, desires, but we couldn't express them because the structure of the Church was then very powerful. But both here and there we try and take advantage of the loopholes. What I always say, and the saying is not mine: “All walls, even the most solid ones, have a small cracking. Start out there!” This is how we started. We set off, doing little things, on foot.

May 68, Burgos, ETA… Male faces are the protagonists. Also those who abandoned habits, men. They say. What about the woman?

At that time we were not talking about ourselves. The woman was not “important”. They didn't value us and they didn't value us until we started to say. “We are too!” Women are an important part of this society, we are more than half, but we wake up very slowly. It was a revolution without violence. That is not what we are talking about, but we should talk about it. We do not want violence, violence comes from outside, but we have wanted to fight without violence, we men have tried to get you into it, and we have achieved it little by little. We have brought about changes, without violence, in a world full of violence. For us there was no more strategy. We knew that if we played forcibly, we would lose the river. And we're dealing with other paths to change. For example, in 1980, I came back from America and went to live in Altza.

In the district of San Sebastian...

Yes, in San Sebastian. Altza, a working-class neighborhood, excellent, with lots of entrepreneurs... We created all kinds of associations: senior citizens, women… I remember that women denied themselves the right to spend money. He didn't even think of going into the tavern alone and having a coffee. We started out there. “How much does your husband spend a week? How much do you spend the two together on Sunday afternoon’s walk?” We calculated and decided: “Well, you too have the right to spend 50 pesetas.” That's where we started in that women's association. It was awareness. Many of these women worked before they got married, got married and left their external needs. However, they believed that the money was from their husband and not from anyone. In religious life, the same thing, no husband, but we lived closely tied. We started questioning everything, asking questions, questioning things…

You're doing it when you came back from America…

Yes. I studied social work and went to the United States in 1971, for six years. Carmelita has communities in America, especially in Latin America. But they needed a social worker in Washington, and I was invited to leave, and there I was, in the Federal District, working with people from Central America. Latinos were already numerous. The women's movement was strong, middle-class women, I mean. The person at the bottom lived the anguish of work, and I thought nothing else. I worked with them, helped in everyday problems and also helped in women's awareness. They had to learn English, take care of their children, send money home... They could not have time to think about the woman with conscience. However, we take some ducks and try as well.

What did you learn in those years from Washington?

It was the time of Nixon, the question of Watergate and other things. That American society seemed very small, teenage. Until then the Constitution had been regarded as a sacred thing and, in his view, no one had violated that text. At that time, it was found that President Nixon had committed a violation of the Constitution in the country. The disappointment of the people! The return from Vietnam was also there, the veterans came completely agitated, that is, attacked by the head. There were major protests against the Vietnam War. Something had broken inside the people. It was a big seizure. I believed in the authorities, but he saw that he couldn’t believe… I remember being in Arizona for six months, in Merikopa, with migrants coming from Mexico to gather oranges.

It's Rio Grande...

They came through Rio Grande or through the desert. They went to the big farms, in the middle of the Arizona Desert. They were little oases in the desert. I would enter the camps as a social worker, and I would help myself as a man. Others studied the employment situation. One day we were kicked out of the camps. Of course, we entered without permission. We were denounced and we went to court. It was very significant: the judge asked me why I hadn't come to the sheriff. I asked him: “In my experience, I would never turn to the police in my homeland for help. Don’t think about it!” They were difficult times. When we were doing a small demonstration, we had the police at our side, but we were supporting us so that nothing would happen to us. The police were there to safeguard our right to demonstrate! We also stand before the White House. In that group we were about thirty: photographers, filmmakers, civil rights activists… people of all kinds. I was there six months and it was a wonderful work experience. The government paid me that, you do not believe. I have learned that his employment situation has also improved and I am delighted. It was 1979. For many years...

The Arizona judge asked him why he didn't go to the sheriff. You, in your hometown, wouldn’t even think that…

I don't. But each of us, in the group of seventeen, would have had a different view of it. Each had its political and social tendency. We were different.

1975, the year of Franco's death. You went to Washington in full force of your fascist regime.

Yeah, I was there. We received a call from the Spanish embassy. We were called to all the Spanish communities that we were there, saying that Franco had died.

Your reaction?

Think about it! Ha, ha, ha, think! Some are happy. We also had Americans, who received the news without coldness. It was time to say, ‘Finally!’.

Vicenç Navarro, professor of Public Policy, is located in Vitoria-Gasteiz, where he has served as advisor for Public Policies. He said that we still live the consequences of that fascist regime, the weakness of democracy and others.

Yeah, yeah... Look, when Franco died, we had two bertsolaris in the Washington Convent. They would say they came from the Idaho side. [Jon] He was a Lopategi, because his two sisters are ours, the Carmelite nuns, and they were with us in Washington. The bertsolaris stayed on the excuse of seeing the sisters of Lopategi. We celebrate in verse the day Franco died!

What did you bring from the United States?

Lots of things and good. On the one hand, I met other Christian confessions. There was nothing but nationalcatholicism here. I worked in the United States with several communities. Some were Christians and others were not. However, all of us who worked for the Latin American community were nothing but fights, nor reproaches. Everyone believed in himself, but we worked at the same time. On the other hand, I met the people of America, full solidarity, wrestling. Human associations were thousands. It is a people of great solidarity. I see none of that here. I have been here for years, but I do not see a culture of solidarity or volunteering. In North America, they were going to ask for a job and they highly valued having done some volunteer work, like when I was a student. There's nothing like that here. Here, still, women are more supportive than men. Man has not yet been actively involved in the work of solidarity he is carrying out. Well, in the Association of Adults, most of them are men, they work hard. But the culture of solidarity, the culture of solidarity, is far away. To put it in some way, I have to give back to society everything I've received in this life, and not necessarily for a salary. Also in exchange for a salary, because we all have to eat, but not just. Life is long, we have an increasing quality of life and we must be aware that we have to return to society what we have received. Even more so our generations. In my generation, many women only had the chance to go to school for eleven years. I was lucky enough to learn, to prepare myself, to leave my country and to have experience. The truth is, it wasn't very normal. The women of my generation have fought, and as a result they are more prepared than men. The man thought it was enough to work – sometimes he had no choice but to do black work – but the woman had another sensitivity and prepared herself.

Social Work, countless associations and projects in Altza, Phone de la Esperanza, Aterpe, Caritas Support, Evictions…

All the projects are good. In all the projects there are enlightened, committed people… I am also a member of Amnesty International and I endorse his motto: “In the dark, don’t curse her. Instead, turn on a candle.” I think in this world you have to turn on a lot of candles, whatever they may be, but turn on candles, turn on a little light. That's my way of thinking, and that's what has moved me in this life. And Jesus' project encompasses everything. First of all, it's humanizing, and in that, I also try to humanize and accept people in what it is. Nothing else.

(Arakaldo, 1944). Moja karmeldarra, emakume konprometituta. Nazareteko Jesus du erakusle, eta haren bideari jarraiki, pertsona du ardatz. Feminismoa, Eliza bestelako bat… Eta, beti, proiektuak, pertsona helburu, behartsuak, baztertuak, immigranteak... Caritas Laguntza-n ari da 2001etik hona. Erlijiosoa izan ez balitz, emakume konprometitua izango zatekeen. Hala ere, damurik ez du, emakume ezkondu askori eman ez dizkion aukerak eman dizkiolako berari erlijio bizimoduak. Esperantza du Frantzisko Aita Santuan, “Egunsenti berri bat”.

“AEBetatik Altzara etorri nintzen. Azpiegitura gabezia handia zegoen. Auzoekin bildu eta elkarteak sortu genituen, era guztietakoak. 1980an berrogeitaka elkarte genituen Altzan, hogei mila laguneko auzoan. Urte batzuk hor eta Gizarte-langintza eskolan jardun nuen irakasle. Gero, Aterpen lan egin nuen hamabi urtez, kaleko jendearekin. Boluntarioak ginen denok. Ehun baino gehiago ere izan ginen. Itxaropen Telefonoa ere abiarazi genuen… Harako fitxatu nuen Esperantza Miner, emakume bikaina, oraindik orain hil da. Blanca Garzia ere hantxe utzi nuen, Aterpera joan nintzenean. Beste emakume bat, handia, Esperantza Arrue…”.

“Komentuan, gure egitura oso estua zen. Kanpoan zer gertatzen zen jakiten genuen, hala ere. Familiaren bisita jasotzen genuen eta ez ziguten ezer ezkutatzen. Kontatu egiten ziguten. Beti hitz egin izan genuen etxean honetaz eta hartaz. Gerra, adibidez, buruz ikasi nuen. Eta gerra ostearen berri ere izan nuen, nahiz eta nik urrunago bizi izan nuen kontu hori. Gure etxean ohikoa zen gerraz eta politikaz hitz egitea, beste etxe askotan ez bezala”.

“Gure etxean, Arakaldon, oso euskaldunak ziren, abertzaleak. Bai aita, eta bai ama. Etxean euskaraz hitz egin ziguten, txikitatik. Euskaraz hazi gintuzten sei neba-arrebok, euskaraz baino ez! Baina eskolara joan, eta gaztelania zen dena. Gaztelaniara jarri ginen. Bilbora joan ikastera, eta gaztelania. Gasteizen, berdin. AEBetan, latinoamerikar komunitatearekin lanean… Euskara galdu nuen arte. Dena ulertzen dut, baina kostatu egiten zait hitz egitea”.

“Emakume naizen aldetik, erditu banintz bezala da. Ez dut mundura umerik ekarri, baina bai proiektuak: gizartean arrastoa utzi dut haien bidez. Ezin da mundutik ibili arrastorik utzi gabe. Arrastoa utzi beharra dugu norbaitengan, edo zerbaitetan, baina arrastoa utzi”.

During a routine excavation in the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome, archaeologists carried out the IX-XIII. They unexpectedly found the remains of a palace dating back to the centuries. And they think it could be the residence of the popes of the time. In other words,... [+]

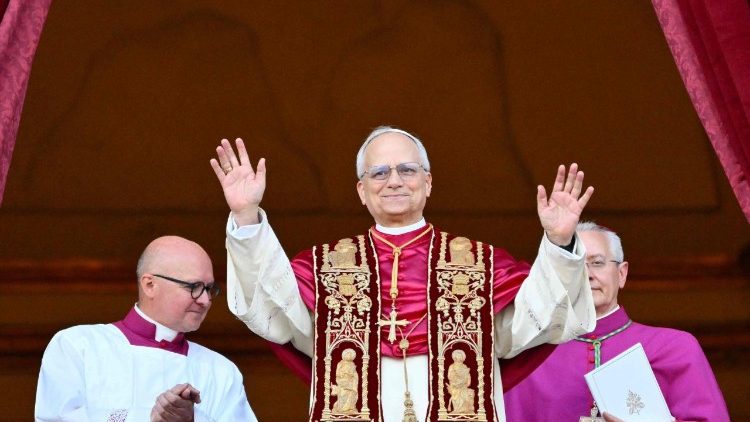

Frantziskok "Franciscomanía" zeinuarekin hasi zuen bere Aitasantutza. Fenomeno soziologiko horri esker, Vatikanoko boterearen zirrikituak aldez aurretik ezagutzen ez zituen gaztetasunaren ikono eta Elizako aldaketa-haizeen intsuflatzaile bihurtu zen.

Era berean,... [+]

Prentsaurrekoa eskaini dute ostegun honetan Marc Aillet Baionako apezpikuak, elizbarrutiko hezkuntza katolikoko zuzendari Vincent Destaisek eta Betharramgo biktimen entzuteko egiturako partaideetarikoa den Laurent Bacho apaizak. Hitza hartzera zihoazela, momentua moztu die... [+]

Elizak 23 kasu ditu onarturik Nafarroa Garaian. Haiek "ekonomikoki, psikologikoki eta espiritualki laguntzeko" konpromisoa adierazi du Iruñeko artzapezpikuak.

Lestelle-Betharramgo (Biarno) ikastetxe katolikoko indarkeria eta bortxaketa kasuen salaketek beste ikastetxe katoliko batzuen gainean jarri du fokua. Ipar Euskal Herriari dagokionez, Uztaritzeko San Frantses Xabier kolegioan pairaturiko indarkeria kasuak azaleratu dira... [+]