"As in other peace processes, ours is also the truth"

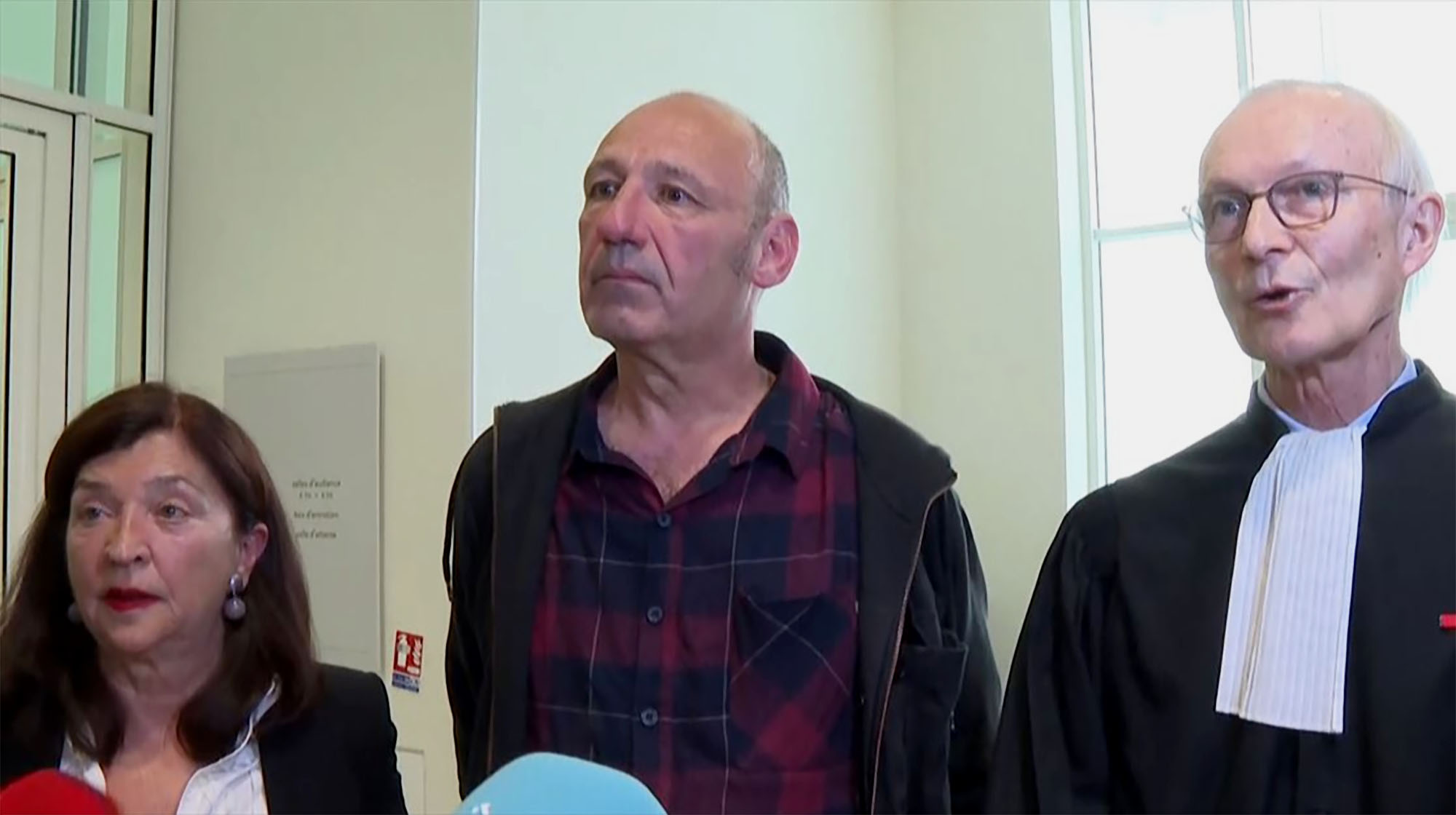

- Portugalete 1968. He grew up in Bilbao and lives in Durango. Professor of Criminal Law at the University of Leioa (UPV/EHU). He has been the Director of Human Rights of the Basque Government. He is currently engaged in teaching. We have brought your thoughts here on criminal law, human rights and the process that could change the political situation.

We have talked about the Parot doctrine and the eviction of the Basque political prisoner Inés del Río, as well as the reactions that the decision of the Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has provoked in society. You have answered our questions in a nuanced way. The speed of events has wiped out many of these responses. We have moved here your vision of the new political time opened after the judgment of the Court in Strasbourg, which you have pronounced masterfully.

When we talk about the Parot doctrine, we refer to the area of criminal law. How is the situation of criminal law in the current justice system?

In the last twenty years there has been a growing use of criminal law. The system of control of justice is abused, compared to civil, administrative, social or educational law. The law must adapt society's areas of action, it is not good that justice should be invoked with hammer threats. To be good, you have to use it in moderation. If criminal law is abused in society, it inevitably becomes an authoritarian society.

Is it more evident in the Spanish State and in Basque society?

Not especially. In general, criminal law in Europe has become a rapid political instrument. It is used from power and is often scammed [fraud]. It is easy to pass the law, but it would be better to analyse whether the law serves to solve the problems. For example, instead of legislating, more money should be put into education. However, when there are problems, the State resorts to criminality so that people are calm. Of course, if it is used in all cases it is not reassuring, but criminal law creates problems.

How can international or European law contribute to political normalisation and the peace process?

I do not know whether the Strasbourg Court can help on all these issues, it can control some things, but others cannot. Strasbourg lays down minimum standards, but over and above these minimums there is no way to control them. For example, the dispersal of prisoners is a standard measure in international law, prisoners should be as close to their homes as possible so as not to break ties with their families and society. But this cannot be done through a court. Europe can help us to work on the political moral sense. In other words, although standard measures cannot become a right, the Strasbourg decisions can feed public debate. That is the fight against the law: if we are right, if it is reasonable, if human rights standards are in our favour, we can act time and time again to influence international opinion and make the opinion of the Europeans favourable. This can release pressure and alter the correlation of forces in politics here, but not through court decisions. Despite

the repeal of the Parot doctrine, the penitentiary policy of the Spanish State remains an obstacle to the normalization process.

Yes. The Criminal Code of 1995 contains the spirit of the Parot doctrine, so these penalties will be applied. Those who have a blood crime should be between 30 and 40 years old. Henri Parot was sentenced to death under the new code, so they remain in prison. The Parot doctrine has beaten some 100 prisoners, so about 500 prisoners of eta will remain inside.

A big problem for the future.

The problem is that prisoners work in a single block. If there is a will in prison policy, rather than in the block, but depending on the crimes they commit, the situation of the prisoners could begin to unblock. It is not the same to kill five or six people who belong to a political group to which they were outlawed. There are therefore different crimes that should be looked at differently: Who has a blood crime? Who can't? And as a result, change prison policies. People who do not have blood crimes may be on the street with the third grade or on probation. The extent of their crimes is not so great, as if they were willing to pay civil liability they would be to a standard extent. Provided that they are more or less willing to redress the facts and do not involve risks of crime. And now, ETA prisoners are not at risk of delinquency to the extent that ETA does not exist.

If the situation of prisoners with serious crimes can be facilitated so that it is not fully complied with?

Other policies will have to be pursued with these prisoners. As has already been said, if prisoners were classified differently, the block of these people would be smaller. The amount would be reduced in the punishment numbers and, at the same time, ways of approaching them could be explored. A more rational policy would help to ease suffering. However, let us not think that all of them will be on the streets tomorrow, because some have committed very serious crimes. A minimum of strategy would be needed to start, little by little, developing another prison policy.

How do you see the steps taken by the prisoners over the past two years?

They have taken a few fundamental steps. If you seriously address the issue, you cannot make block policy. ETA has to recognise the maturity of the prisoners, ETA prisoners are not a block. They're people. In order to force the State to change its prison policy, the bloc character has to disappear, the people who own it must be recognized, so that each of the prisoners takes their steps. These are undeniable steps. Prisoners can make gestures, such as saying that they are willing to pay civil liability and acknowledge that they have done harm.

What prevents it from being made possible?

Prison policy has become an instrument of ideological confrontation. The State uses it to achieve victory, ideological victory. Moreover, it has gone beyond ideological victory, it has overcome the ethics of human rights. In other words, crimes must have a responsibility, but that must not force the prisoner to give up his ideology. The statue has gone too far. But in addition, ETA has used the State's penitentiary policy to lobby, to make its policy, it has contributed to keeping the prisoner in chains.

Where are the limits of law and law in the Basque political sphere? Is there any possibility of moving forward?

As in other peace processes, in our case, the key is to know the truth. As long as the truth is not revealed, the political correlation of forces will not change. Policies had to be articulated, and we were aware that the State had the responsibility – and, of course, the political interest – for everyone to know what has happened. The accounts of the people killed by ETA have been carried out, and that is OK, because that difference was very bad. But not everything is in the hands of the Spanish State. If we want to change in this country, we must make known to Basque society the victims that the State has created, the excesses that it has left hidden. We should be able to do this. The explanation for this part of the truth can alter the correlation of forces and the political debate. And for that we can't use judges, but we can use the law. At the CAPV we have sufficient competence to put in place small pro-truth mechanisms.

So you can start to channel.

There's a very small, very low principle. The decree was approved in the Basque Parliament in 2012. The Decree on Victims of Terrorism covered a number of human rights violations in the period 1960-1978. This tool has opened the way. It was approved by the Basque Government and that policy is in progress. A total of 100 victims have been counted, but if that decree were amended, the cases of victims would be studied and supported until 2013. Violations of human rights committed by the police, with their consent or push, as well as by uncontrolled, can be made public officially. The mechanism is created and needs two conditions to work: one, fair play by most aspects. Consensus among all is difficult, but with sufficient consensus progress could be made, because in the field of human rights there is no right of veto. Two, a clean game, because each party must recognize that it cannot impose its story on the other, because each party is very convinced of its story.

The parties have to take the steps.

Yes. But the real mechanism cannot be created within the parties, but within the organizations. The parties want control of the mechanism. In this regard, for example, if the Abertzale left accepted that its people should go to institutional mechanisms, because many of its people have suffered human rights violations, the effect would be enormous. But that can't be done by saying, "Let's go together." For example, with the complaint of 4,000 people. This must be done through a process, making play clean, agreed, creating a mechanism of truth between the parties for three or four years. If, at the end of it, the human rights violations committed by the State had become apparent, would we not all be much better?

The need for transitional justice is increasingly being heard. What is that?

Some deny the so-called transtctial justice, because they think it is proposed by the Basque left. They are therefore against it. Others think that we are not in the transition here, that we are not changing from dictatorship to democracy. Transtctial justice was born in Latin America and Eastern Europe. It is the new field of the right to justice over the massacres of the past. Transitional justice is not closely linked to political transitions. Its objective, on which we can all agree, is to implement the right to a society that seeks to redress the serious violations of human rights that have yet to be dealt with in a people. Anyway, if someone doesn't like the name of transitional justice, let's banished it and call it justice.

It seems difficult, but in a way, you see ways to start the standardization process.

In a way. On the one hand, although in a fractional manner, as the process progresses, all the victims would be better off and, at the same time, we would establish another pillar for cultural policy. The debate on the current report may be different. But that requires making realpolitics and trusting them. It's not easy, of course. “Will I trust the Abertzale left?” “Will I trust the PSOE and the PP?” “Or the PNV,” politicians say. Audacity and intelligence will be needed to create that opportunity. If this were to happen, albeit small, the second step of the decree I mentioned earlier could be taken to unblock the situation. We say it's not in our hands, but it's in our hands.

In the hands of whom?

The decree would be in the hands of the Basque Government, but in the future we could also think of a law. That is, if we cannot go to criminal justice, if we cannot do it through the judges, because that is not in our hands, under the administration of Spanish justice, and because they have a different view of what is happening here, we, at the CAPV, could resort to our legislative power, and if it is partial, take steps to create a process. And creating a process does not mean that nobody has to give up their goals, that everyone has to keep their goals and ideologies, but that we are on the way to making progress on the issue of human rights.

But it's hard to do the whole story.

We are not going to see the story of everything that has happened. But the story of the people murdered by ETA has brought concrete policies. I am convinced that as the other truths, the truths of all, come to light, the story will change. If we are able, the story is transformed spontaneously into what has happened. If people see someone being tortured or killed, through the terrorist band, paying money, as we've seen in the Lasa-Zabala case, it changes people's vision. The situation will change over and above the ideology of each and ensuring respect for each of them.

Will the Spanish State recognize that torture has been practised?

The biggest problem will be that of torture, which will cost the State the most to recognize it, even though the Constitutional Court, the National Court and the Supreme have long been, not systematically, but on more than one occasion they are saying that “we cannot say that they have been torture, but they have not been properly investigated.” They're recognizing that they looked elsewhere. On the subject of torture, however, we must also move on to a second phase. There has been a first phase, from a political point of view, in which there has been a clash: “Has there been torture, yes or no?” Data on torture must now be formalised. There are two extreme theses: The Minister of the Interior usually says that "he has not been." There are cases condemned by the judges, twelve cases punished by the old code. The new penal code. Torture does not officially exist since the 1990s. On the contrary, others report having 10,000 complaints, one before the judge and the other officially filed. What is zero and 10,000? Therefore, a real mechanism must be created and for this purpose there are protocols of the forensic doctor. I mean, it's not worth telling us, but I told a medical judge. Of course, there will be no perfect mechanisms, but the subject of torture can come within the definition of those two extremes. If we open that intermediate path, it can be our “heritage”.

Parot doktrina deuseztatu ondoren ezker abertzalearen jarrera adimentsua izan da. Lehen Estatuak gehiegikeriak egiten zituen, eta ETAk ekintza injustuak egiten zituen berriz ere. Gurpil zoroan geunden. Orain ez dago hori. Egurra ematen duenak –Estatuak orain– defentsarik gabeko corpus sozial bat aurrean baldin badu, corpus hori azkenean kontra bihurtuko zaio. Dagoen sufrimendua izanda, legeak muga dauka. Orduan beharrezko da prozesu bat sortzea bestea mugiarazteko, eta ezin baduzu sortu, gutxienez, baldintzak sortu behar dituzu zure esparruan. Ezker abertzalea horretan ari da. Zoritxarrez, joera hegeliarrak oso hedatu dira, pragmatikoagoak izaten ikasi behar dugu. Lehenbailehen eta adimenez jokatzea hobe.

Erabakia oso ona da. Estrasburgok –giza eskubideen sistemak orobat– gutxieneko eskubide batzuk baino ez ditu kontuan edukitzen. Estrasburgok arrazoia ematen ez badizu ere, horrek ez du esan nahi arrazoirik ez duzula. Alegia, giza eskubideen estandarra gutxieneko sostengurik gabe gera daiteke. Kasu honetan Estrasburgoko auzitegia minimo horietara heldu da. Handitu du babes estandarra. Argiago esateko, orain arte Estrasburgotik delituak eta zigorrak nola definitzen diren kontrolatzen zen asko, baina soilik legeari dagokionez. Aldiz, gutxiago begiratzen zitzaion behin kartzela barruan gertatzen zenaren inguruan. Epai honen bitartez, ez da bakarrik kodean dagoena kontrolatuko, baizik eta kodea aplikatzen denean, pertsona kartzelan dagoenean, egiten diren espetxe politikari buruzko esku-hartzea izango da. Erabakiak bermeak ezarri ditu espetxe barruan, ez da formaltasunetan geratu, iraganean geratzen zen legez.