Solidarity and resistance against fascists

- When in 1937 the Basque army fell into the hands of the fascists, the baztanese Bittori Etxeberria and other women created the first secret network of solidarity. The information sent to the Basque Government was very valuable in helping the prisoners. This institution had a sad ending, but its members were arrested and one of them, Luis Alava, was shot along with the sunrise 70 years ago. Since then it has been called the Alava Network.

On May 6, 1943, the customary death commission departed from Porlier prison to the Almudena cemetery in Madrid. He had ten Republicans and Socialists to fuse the trucks against the cemetery wall, and with them a helmet mate, Luis Alava Souto. The dams of Las Ventas, close to this place, had heard, as usual, shots at dawn. But four Basque women locked there (Tere Verdes, Delia Lauroba, Bittori Etxeberria and Itziar Mujika) knew well who Luis Alava was, one of the gunmen of that day. On the one hand, because they had been comrades and summary, and on the other, because from the day before they knew that he was “in the chapel”, that is, about to be shot.

This shooting solved the question that everyone had in mind since September 1942: whether the Francoists would end this last sentence or whether they would surrender to many diplomatic and political efforts. It is obvious that he won the usual choice. Between May 1939 and February 1944, 269 collective firings took place in the Madrid cemetery, killing 2,663 people. Until the Second World War changed course, the Francoists had no resort to commit these massacres almost every week.

The death of Luis Alavés, in addition to showing the lack of mercy of the franchises, a network that was absolutely paralyzed three years earlier, gave name to the group that acted in it. Since then it has moved to popular memory and media such as Red Alava.

But this sad murder originated in an initiative that goes beyond the name. Although at the end of the organization we have Luis Alava, at the starting point and in the activity there were people who had more responsibility.

From Elizondo to Baiona by Santoña

These women pioneered the creation of the Alava Network. It emerged as a result of the surrender of a large part of the Basque army in the area of Cantabria. At the end of August 1937 in Santoña and Laredo an agreement was signed with several Italian Basque leaders and the authorities of the Basque Government wanted direct and concrete news about its compliance and its consequences.

Mr José María Lasarte, for his part, asked Bittori Etxeberria, the neighbour of Baztan, to know the conditions and situation of the prisoners. Etxeberria started moving threads in Elizondo to create the first solidarity network of Euskal Herria. It was the first link in the chain of connections with the jihadist leaders who were in Ipar Euskal Herria, as well as those who were imprisoned in the rest of the Basque territories.

Together with Etxeberria, two women, Donostiarras Delia Lauroba and Itziar Mujika, took care of the data on the events in Santoña and the situation in the El Dueso prison. They both had good excuses for getting closer and getting information. Lauroba held her husband José Azurmendi in El Dueso, and Mujika held two brothers, one in El Dueso and the other in Ondarreta. In connection with the prisons in Bilbao and Burgos, they had the help of another woman, the bilbain Tere Verdés, since his brother José, was imprisoned in the prisons of Larrinaga and Castilla.

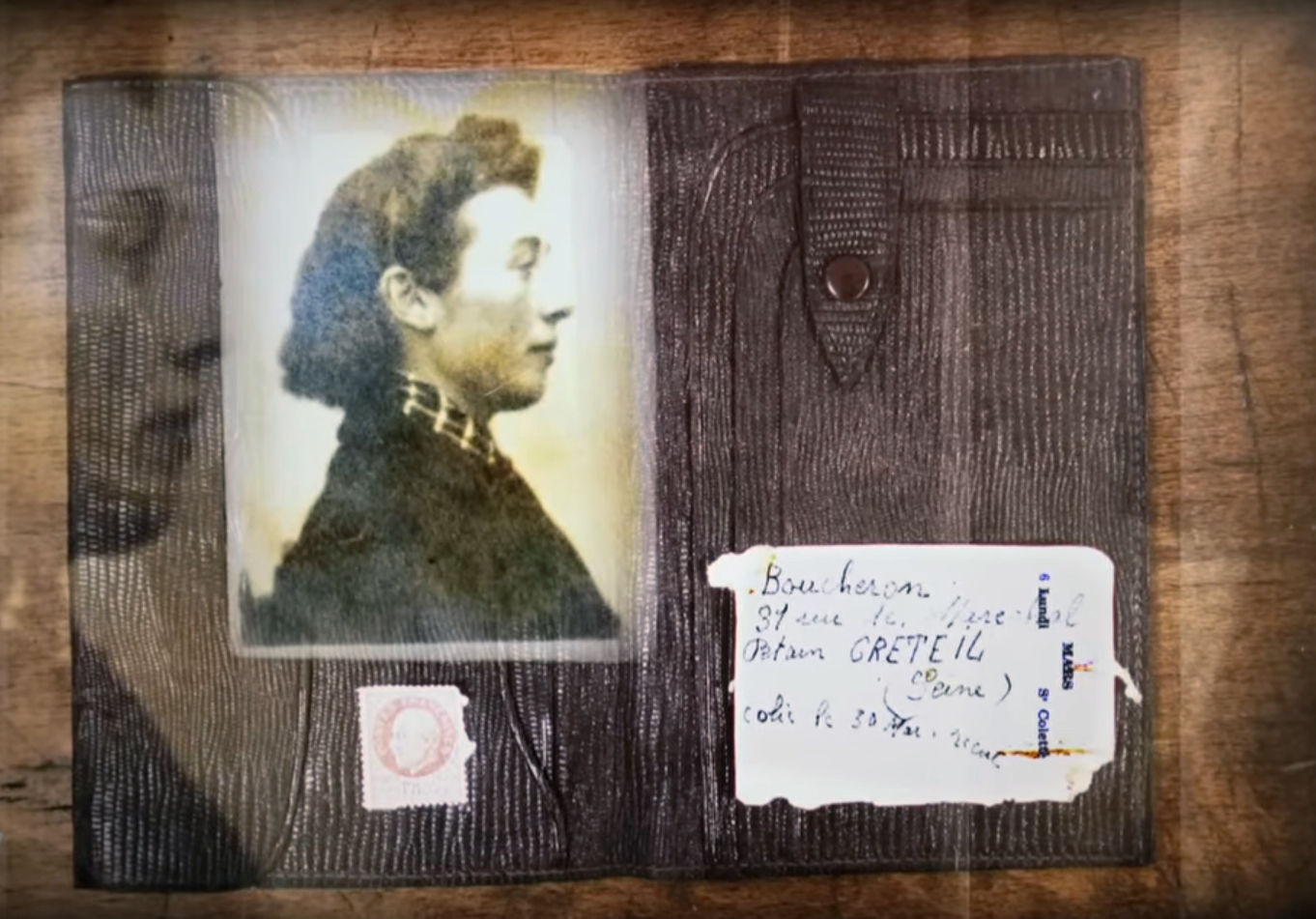

In this network, Bittori Etxeberria was key, as he was in charge of transferring all information on both sides of the border. The report on the Internal Service drawn up by the leaders of the PNV for the Basque Government highlights the role of Etxeberria: “The organization was born of Pepita (Bittori Etxeberria was called Pepita Etxano). It was he who took the first steps, he who opened the way. Today, it remains the fundamental basis of any relationship. At the last moment in Laredo, Pepita Etxano made a clandestine tour. Next, we met him: we consider him to be of providence. He knew the media and there were many isolated abertzales working on social and solidarity initiatives… From the beginning he told us that he had the means, with good hand and with complete security, to ensure communication on both sides of the border.”

These four women were in charge of screwing the sections of the network, as fast as they were robust, extending it beyond the Basque Country. Although the starting point was in Baiona, they soon arrived from Baztan to Pamplona, from San Sebastian to Bilbao and Vitoria, and later, due to the dispersion of the Basque prisoners, the influence of the solidarity network that reached El Dueso, Burgos, Dueñas and Puerto de Santa Maria.

To carry out the dissemination, they were assisted by several participants in all the Basque territories. In Álava, for example, Etxeberria contacted Luis Alavés to be the most responsible for the area. In Navarre he easily managed to expand the organization, constituting the largest group. Specifically, the works of the baztaneses Esteban Etxeberria, Felicita Ariztia and Timoteo Plaza, as well as those of Felipe Oñatebia, Modesto Urbiola, Rafael Goñi Latasa and Felix Ezkurdia. In Gipuzkoa, a good team was also set to work: In addition to the prestigious physician Iñaki Barriola, the program will feature the presence of Inocencio Tolaretxipi, Rafael Gómez Jauregi and Patxi Lasa. The Biscayan team was smaller and based on Tere Verdes, although it had some collaborators, such as Julián Agirre and Antonio Causo, who were in charge of firing.

Objectives of the Network

The main duty of the majority of the Basque army in captivity was to promote aid to prisoners. It was important to maintain the link between leaders in exile and those in prisons. For example, prisoners Juan Ajuriagerra and Jesús Solaun contacted jihadist leaders José Mari Lasarte, Ramón Agesta and Juan Iturbe, who were on the other side of the border. The aim was to transfer information from prisons to Baiona and Paris in order to prevent convictions of prisoners, especially those of death, from being prevented through international agents.

The list of pensioners, the sentences and the summary received by the members of the network were of great importance in maintaining the lives of many prisoners. In addition, the information they received was essential in order to be able to carry out the exchanges of prisoners on both sides, carried out before the end of the war. On many occasions, the work of the network was useless in saving the lives or achieving the freedom of the prisoners, but on other occasions, they managed to replace the death sentences with others.

After the end of the war, the situation worsened. On the one hand, because exchanges of prisoners have ended, and on the other, because repression has become widespread. In addition to increasing the number of prisons and prisoners, other repressive spaces, such as work battalions and concentration camps, spread throughout Francoist Spain. Thus, solidarity with and the need for information about prisoners and oppressed persons increased. The repressive reality of the Franco regime that was to be shown in Europe was approved by Britain and also by France, as a result of the agreements between Jordan and Berard.

But the information was not limited to the issue of prisoners. The second initiative of the network was the provision of information on the Spanish State. Curiosity about the worsening politico-military situation led the inmates' support network to become an information network. The international context, the situation on the eve of the Second World War, further heightened this will for information. In an increasingly conflicting environment after the Spanish Civil War, France and Great Britain considered it necessary to have as accurate information as possible on both sides of the Pyrenees.

Thanks to the Alava Network and through the Basque Government, they were able to know where the Spanish army was deployed, how many riots and barracks were at the border, how the movements of the boats were, the displacements of the Germans, the internal socio-political situation of Spain… The effectiveness of the organization was enormous. Documentation and information packages were sent to the exiles of the Basque Government almost every week. The report seized from the network at Paris headquarters indicated that "over and above books, magazines and the like, 1,242 documents were made available to the members of the José Antonio Agirre Government".

To explain this effectiveness, it must be borne in mind that the tiring of secrecy took place properly. During the time the network lasted, only one of the participants, Agustín Ariztia, who was persecuted by the police, had to sneak. All the others remained active as the network until the report intercepted in Paris put the Spanish police behind its runway.

Prison inside, death by hairs

With the seizure of Paris by the Germans, the Francoists acquired the seat of the Basque Government at Avenue Marceau, today the seat of the Instituto Cervantes for robbery without return. Members of the Gestapo and Franco police localized the report on the Interior Service that was given to them. In this document, although pseudonyms and war names were used, numerous features and data were collected about the network’s incidents: how it was formed, who formed it, what type of action it had… It was at the end of June 1940 and from then on the Francoist police and military records began.

In December 1940, the last meeting between the representatives of the network took place in Vitoria-Gasteiz, in view of the situation of Ipar Euskal Herria and France, in order to decide on its dissolution. They still didn't know that the fascists were following their trail. The Franco police knew first-hand the members of the network to which they belong. A week after the dissolution of the organization, the first arrests took place, at the site where the network was set up, in Baztan. It is Bittori Etxeberria, brother of Esteban and Felicita Ariztia. Subsequently, several more arrests took place in Pamplona/Iruña, Gipuzkoa, Vitoria/Gasteiz and Bilbao. Shortly before the start of 1941, 28 people were arrested in Madrid, after passing through the prisons of Ondarreta, Pamplona and Larrinaga.

Those arrested were dispersed in prisons and Czech prisons in Madrid or in captive areas in the Community. Although at first everyone had been at the check on Fomento Street, after the first interrogations, the women were transferred to Las Ventas prison and the men to Porlier. They had the opportunity to know, from within the walls, what the situation of the Spanish prisons was: in addition to a huge overcrowding of people, diseases, hunger and, above all, fear of death, because you took them – take the prisoners out of the cells and fuse them – into effect.

Many of those who had belonged to the network were close to death, as the court imposed very harsh sentences on them after being tried on 3 July 1941: 19 death sentences and long prison sentences for the rest. However, the judgment was appealed and the second trial took place on 18 September 1942. As a result, the penalty was reduced to a single death – that of Luis Alavés – and to long imprisonment.

After the final conviction, they tried to save in some way the life of Luis Alavés, remembering the work they were doing on the street. But from there things had to be carried out by the skirts of the savage dictatorship, and in the case of Luis Álava, without success. For those who stayed in Porlier and Las Ventas, the death of this comrade was the saddest episode of the solidarity initiative initiated in 1937. That is why, in his memory and in that of the people, since then it is the Alava Network.

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

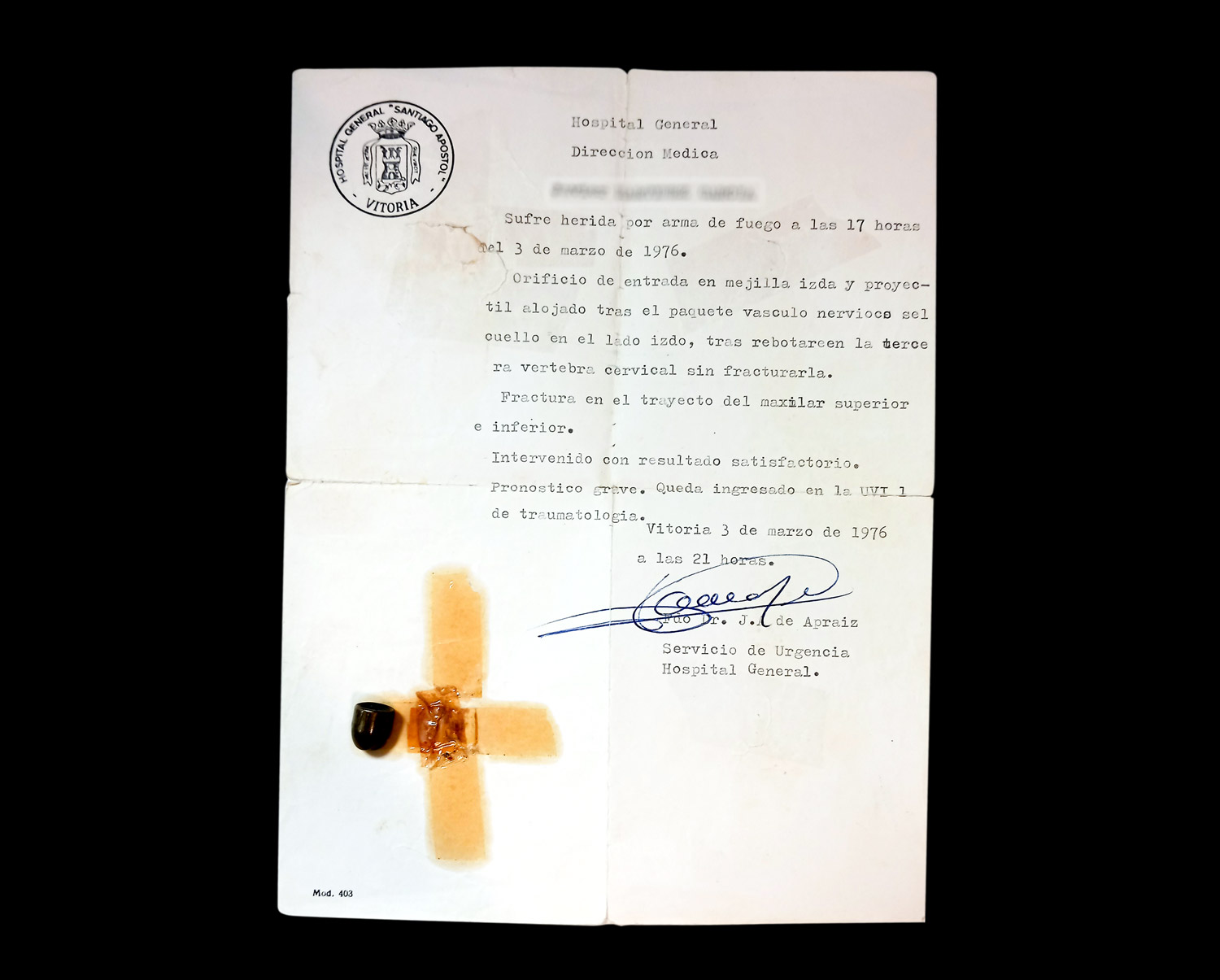

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.