"They want to humiliate us, get out at night by the back door."

- MIL, the founder of the armed groups GARI and Action Directe, is emerging from a fourth century prison in Jann-Marc Rouilla (1952, Auch, Gascuña). The protagonist and privileged witness of the revolutionary leftist European movements of the 1970s and 1980s, now dedicates his memoirs to several books. In other words, it will not stop fighting for a while.

On probation since 19 May 2011. How do you experience that contradiction that unites freedom and condition?

I have no access to 38 French departments, large cities. I have to make a lot of requests to leave France, wait months, until the courts decide that I can leave for five days. I can't lead a normal life, do the work normally. They want us unemployed, they want us poor, they prevent us from dignified day to day. There's a program against former militants who have been in jail, it's generic, I've found a lot of colleagues in the same situation. They don't want to turn the page, and better, because we don't want it either. The struggle is still out.

You can't talk about certain things.

It prohibits me from talking about the acts that I have been condemned. In December 2007, it was the first time I was granted parole. But almost a year later, following what I said in an interview, they took me back to jail. I criticized the anti-terrorist law, and they decided that if I criticized the law, I was talking about facts. It's absurd, but they do what they want. Counter-terrorism justice is a balance between forces. And for the moment, the power relationship is for them.

If they have the power, how do you interpret all the chronology? Abandonment, re-entry, the current situation.

The Action Direct members were four. Joelle Aubron was very ill and died two years after leaving in 2004. Nathalie Ménigon earned the third grade in August 2007. And then it was incomprehensible that Georges Ciprian and I stayed in jail, because our sentence was shorter than Joelle and Nathalie. They took me out, and they didn't like anything: they found an excuse to get into the house back. Finally, in 2011, I left Georges. The struggle has been tough. I remember a number of people, Georges Ibrahim Abdallah, who is still inside after 29 years. And many Basque colleagues, Frederic Haramboure, Jacques Esnal, who should be in jail long ago.

25 years in jail, not counting the times of MIL and GARI. He's just afraid to say it. How do you remember them?

Jail is a struggle, you have to endure it, you have to endure it, otherwise you're dead. From the first day, from the police station, political prisoners are condemned to cooperate, under the threat of a harsh sentence. We were soon sentenced to life imprisonment, because we rejected any collaboration. And they waited seven years to resume our process, making great repression against us in those seven years, isolation, threats, beatings. They expected the image of the group to melt. The first victory was that in seven years we took ourselves out of isolation and had a collective attitude. It was important to do that demonstration. At all times they have raised the issue: criticism of the armed struggle, repentance. In 2010, we were told that if we were to make a text, we were criticizing our actions, we were rejecting the path of armed struggle, we could get out of jail.

Let's go back to Toulouse, into adolescence. Many elements were mixed: Around May 1968, but above all the anti-francoist struggle.

I have had two charms in my life; one, being 16 years old in 1968; another, living in the capital of the Reds – and all those who fought against Franco and were exiled in Tolosa, including many Basques. Three young people who were together at the Liceo created action committees. When we stopped to the question of guns, we had two options: San Sebastian or Barcelona. No more. It was obvious that we would not go to Paris. It was the time of the Burgos process. Former guerrillas contacted us with those of ETA. And, look, the first clandestine action I did in the 1970s was the impression of the Workers, and the publication of the VI, in one of our clandestine printing houses in Tolosa. I met Oriol Solé Sugranyes at the support meetings of the Burmese process, and a ETA official told us that a front had to be opened in Barcelona. We began to think about how to carry out the armed struggle in Barcelona, in relation to what was happening in Euskal Herria. That's how the MIL was born.

Why was Catalonia or Euskal Herria so clear? In other words, why wasn't Action Directe born in 1970?

Armed struggle is something related to a situation. Without May of 68 there will be no armed struggle in Germany, Italy. Without the offensive of the autonomous movement of 1977-1978, there would never have been Action Directe. Some young people now say that there are more conditions for armed struggle than in the 1970s and 1980s. But armed struggle is not a mechanical thing, it takes subjective conditions, an offensive of movement, experience, many factors. The first time I left jail the matter was very weak, but now I am listening to the relevant things. And when we put the question, the answer is already inside, in the reflection of the people who care for it there is already a solution that is on the way to germinate. The offensive attitude of anti-terrorism is also because they feel that something is going to happen, even if terrorism is no longer important. And I think in Euskal Herria there's more or less the same thing happening, that they want everything under control, so you can get through.

How did you see, from the movements of the radical left, not only the action of ETA, of the Basques in general, which was the fight against a regime, but also the defence of one’s own identity?

In the late 1960s, in the early 1970s, ETA was very popular within the French extreme left. But there was a cut. In 1973, the French extreme left rejected two things of capital: first, to support the reality of the international labor movement; and second, to support nationalism. These rejections lead to the abandonment of all the positions of the armed struggle. It was the end of the revolutionary programme of the French extreme left. At that time ETA was still popular, until 1977. And the only ones defending ETA are the Self-Employed, who put the question of armed struggle on the table. I cannot understand that. The movement of the Mute Left is born in the support struggles of national associations and anti-colonialism. And the situation of Euskal Herria was colonial, like that of Catalonia. It is therefore entirely logical that a movement towards national freedom should be supported within the French extreme left. Today many do not understand how one can fight for the construction of a state. Therefore, do we not support the Palestinians any more? In a struggle for national liberation, you first make a free state, it's the basis of the revolutionary principle. And then, if you like, keep fighting the bourgeoisie.

What general reading do you have of ETA’s 50 years of activity and the definitive cessation of violence?

I have had a favourable attitude at the end. I am aware of the difficulties that arise at this time. I think it was best to end this first process and start negotiating the release of prisoners. Because the strength of these political cadres in a legal movement is important. They have a great deal of experience in conducting a real political struggle. It's been 50 years, the armed struggle can stop, it's not a dishonor. Conditions have changed, but a strategic political tactic is needed to manage this phase of the political struggle. Lenin, questioned about the success of the Bolshevik party, said: “Our party has been legal, illegal, has taken the guns, has left the guns, has gone to parliament.” They had an amazing experience, so they came to the Winter Palace. And the first response of a peace process is an electoral triumph, and more and more elections. There's a 50-year-old story. And if someone has done something for Euskal Herria, it's ETA and not the others, who are presented under the banner of pacifism, of legalism. Now is the time to manage the political issue, knowing that it can only be done with the Spanish right, because the left will always have the opposition of the right.

It talks about the release of prisoners and Spain offers individual solutions; it talks about repentance, forgiveness.

Among the members of Action Direct, we agreed that there will be no individual solution, that we enter into a political struggle and that we come out with a collective solution. It's not a satisfaction, but I'm glad I came out the last one, because I haven't left anyone behind. If you start with apologies and the like, the Spanish Government must apologise for the occupation of Euskal Herria, for the murdered, for the tortured. You can say that until this does not happen, you won't ask for forgiveness. There has been a fight, there have been deaths everywhere, it would be fair. Those who have taken arms are also victims, or rather have taken arms to prevent them from becoming victims of violence. The point is that they do not respect their own rules either. We have seen this in the history of Germany: for twenty years they said that if Rote Armee Fraktion left the guns, they would release the prisoners. Following the RAF's abandonment of arms, the release of the prisoners continued for 4-5 years, as they knew it would be a tremendous triumph. They don't want to confess, they want to humiliate us, they want to go out at night through the back door. The idea they want to pass is that they don't welcome us. They don't want 10,000 people in front of Martutene.

After 50 years of logical struggle, is it not enough to talk about a dignified departure from prisoners?

It's just one step. I think that ETA’s victory is not possible at the moment, because we are at an ultra-reactive moment. It's not winning time for anyone. But the peace process is not a failure of ETA. Spain’s treatment of the process is a failure, it is being carried out in a ridiculous way in the face of international opinion. It is a peace process and there is nothing to negotiate, there can be no consistency. I believe that Euskal Herria exists as it is now because in 1959 there were young people who exerted great pressure on the Spanish state. Autonomy is at least the first path to independence. One day Spain will explode. Now it's held because the power of force is on its side.

You trust that “not having broken your dreams” in the 70’s when you wager on weapons, would you say the same thing today?

I still have high hopes. I've spent a quarter of a century in jail, I'm older than before, I'm sick, but I'm still prepared for all the revolutionary adventures. Knowing also that revolutionary adventure can happen at any time.

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

Bilbo, 1954. Hiriko Alfer eta Gaizkileen Auzitegia homosexualen aurka jazartzen hasi zen, erregimen frankistak izen bereko legea (Ley de Vagos y Maleantes, 1933) espresuki horretarako egokitu ondoren. Frankismoak homosexualen aurka egiten zuen lehenago ere, eta 1970ean legea... [+]

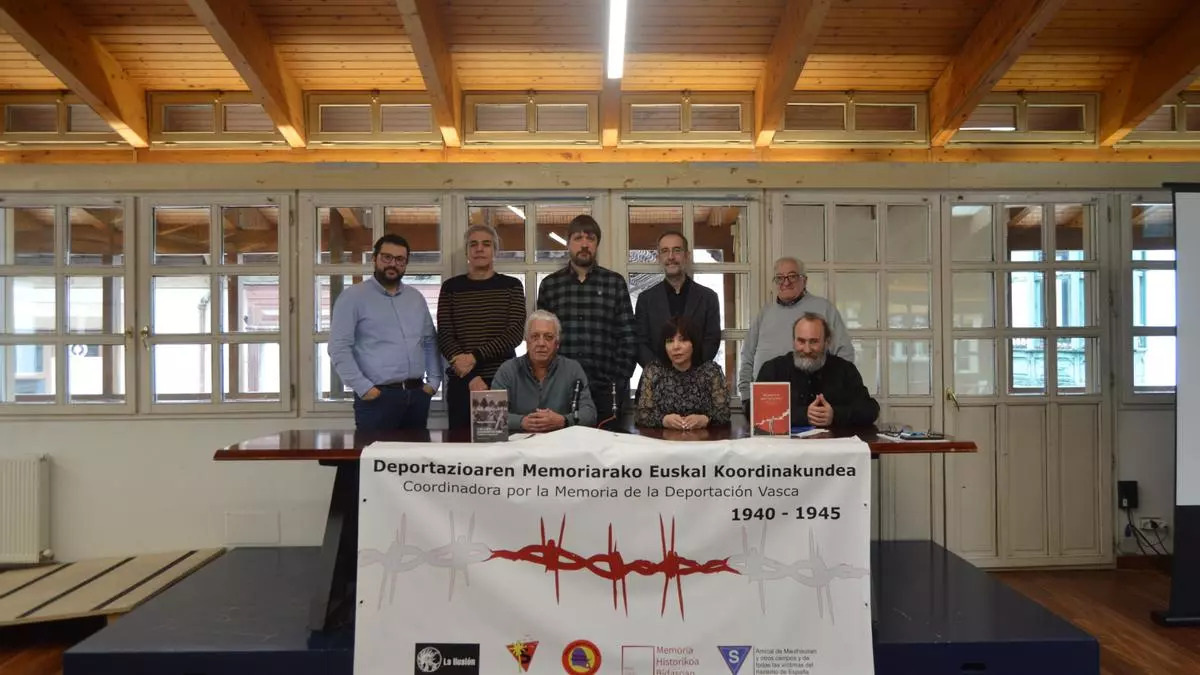

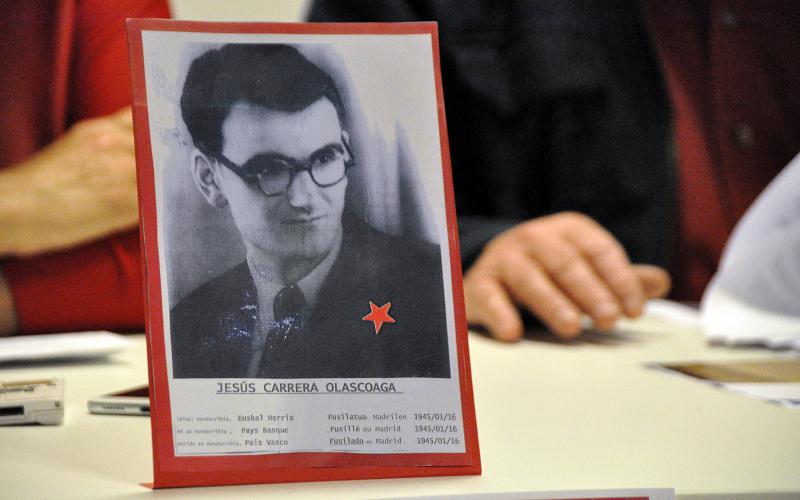

Deportazioaren Memoriarako Euskal Koordinakundeak aintzat hartu nahi ditu Hego Euskal Herrian jaio eta bizi ziren, eta 1940tik 1945era Bigarren Mundu Gerra zela eta deportazioa pairatu zuten herritarrak. Anton Gandarias Lekuona izango da haren lehendakaria, 1945ean naziek... [+]

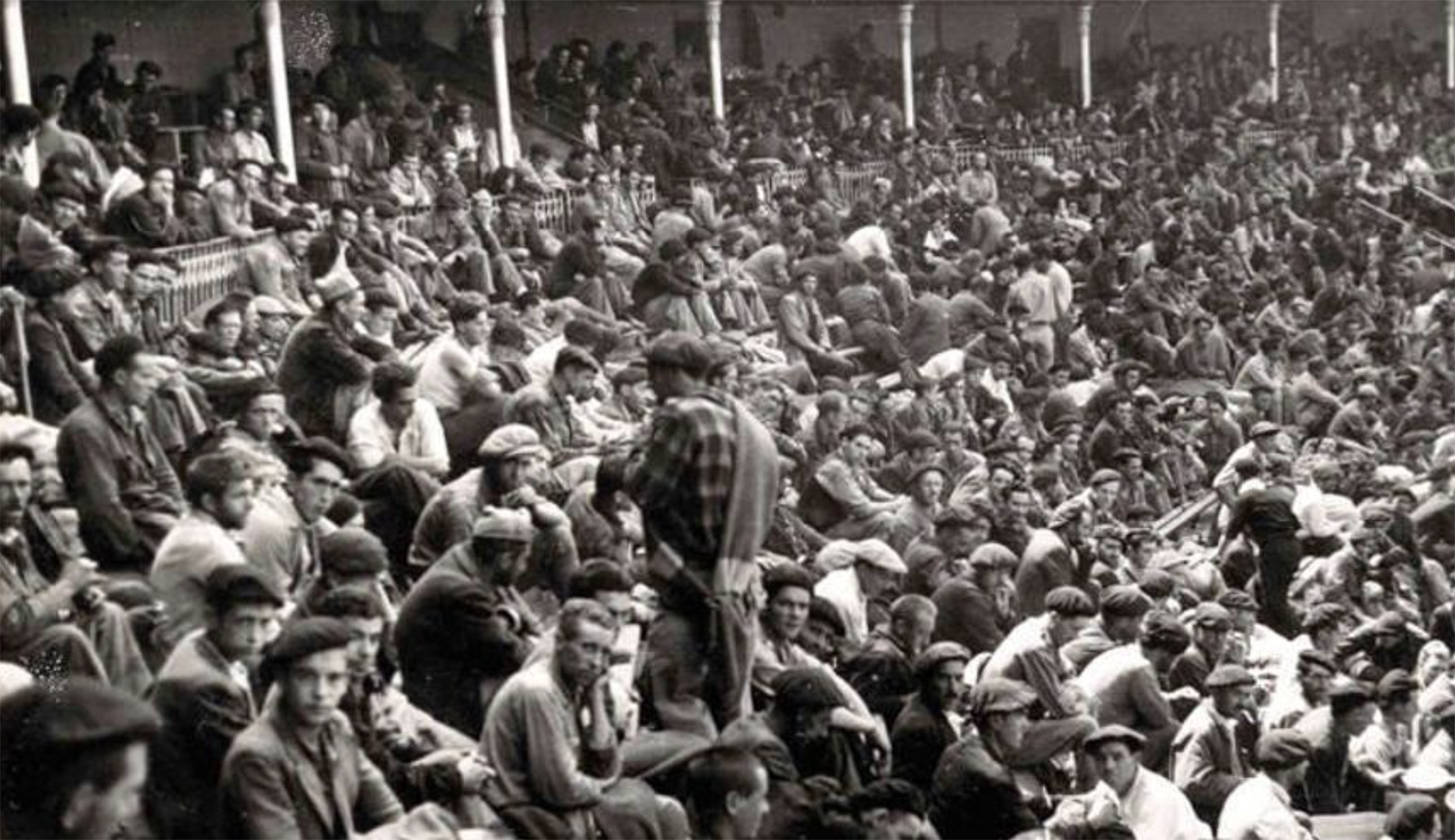

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]