At the end of road

- They are the last representatives of a tough and fighting generation. They're over 95 years old. They are gudaris and militiamen of the 1936 Civil War. Talks, tributes, letters to newspapers… In the last part of life, they continue to fight for their ideas and their freedom: Anarchist Félix Padín, nationalist José Moreno and communist Marcelo Usabiaga continue to shoot the words from the trenches of memory.

“We made the road from Vidángoz to Igari in a battalion of disciplinary workers between 1940 and 1942. About 600 prisoners. All by hand: we brought the quarry stone into large pieces, transported it with the wheelbarrow to the road drawn and, little by little, crushed it and extended it with the pertiga. We were getting more and more crushing stones! Then to Gipuzkoa: Gaintxurizketa, Lezo, Errenteria, Oiartzun, Zarautz… We thought it was going to be like this for our whole lives!” Felix Padín (Bilbao, 1916), lieutenant of the anarchist battalion Durruti, remembers the terrible memories that forced him to make the roads.

Near there, in San Sebastian, Marcelo Usabiaga (Ordizia, 1916), former lieutenant of a militia and anti-aerea republican battery of the Communist Party's Rosa Luxembourg battalion, also had to make a famous city road, prisoner: Avenida de Tolosa. “On foot we were taken from Ondarreta prison, and my job was to drive stone-filled cars, along with three other prisoners. All this you see was the mountain at that time. By the time I arrived, there was only a lack of covering the stone road,” he says with a loud voice in the Ibaeta district of Donostia, while this road is stepping.

After many years of building infrastructure, they had to suffer the persecution of the dictatorship. He was also sentenced to long decades in prison. Subsequently, the Transition and democracy plunged societies into oblivion. However, as soon as they were granted freedom, the struggle continued, each to the extent possible.

José Moreno (Deusto, 1818), gudari of the San Andres battalion of STV-ELA, also spent his time in the workers’ battalions. In 2005, with the intention of honoring all those who have worked for democracy, he founded the Aterpe 1936 association, together with other fighters. And to be president. Moreno's goal was to place a monument in Artxanda to pay tribute to all the gudaris and militiamen: "I'm a nationalist, but I didn't think it was good to just talk about the gudaris. Here everyone fought, communists, socialists, anarchists, nationalists… And that plaque we put in 2006 is for all the battalions, for all those who suffered in the Basque Country. It cost us a lot, but in the end we managed to put it.”

Questioned by the founders of the community, the warrior regresses in time: “There was José Mari Otxoa from Txintxetru, that other anarchist, a comrade… But they are dying, we only have two or three.” However, Moreno approaches Artxanda every year, for the seventh year in a row, on June 18. It's the last of the soldiers. “If God wants, this year I will also be.”

Brother leaves the subsoil

As soon as democracy arrived, Marcelo Usabiaga dedicated himself to seeking Brother Bernardo, shot and buried. In 1978 he went several times to Pikoketa in search of the settlement of the buried, until he sought: "Immediately after his arrest, some seventeen people, some of them aged more or less, were shot in the vicinity of a village dwelling. The owners of the cottage didn't mean where they were buried. In the end, talking to a nephew, he explained more or less where they were.”

Said and done. Usabiaga began to remove the earth with the help of the relatives of the others shot and suddenly, what until then was nothing but an illusion, became a reality: they found a currency. There were the dead. All the remains were taken and buried together in a mausoleum from the cemetery of Irun. “We didn’t want to know who each bone was. We wanted to recover them, dignify them. Nothing else,” says the communist, without reminiscence.

In full democracy, anarchist Félix Padín revived his militancy. He participated actively in the meetings of the CNT trade union in the Spanish State, where he became his residence so that the CNT could access the premises in Miranda de Ebro. “When we started, the meetings we were doing in my house. In 1989, I started my efforts in Bilbao and a friend, and I started to recover the Miranda de Ebro union. In 1990 it was already working and we made it official at the age of two,” he says.

Since then, Padín has become a symbol of anarchism in the people, it is also a reference in the Spanish State. In 2011, on the occasion of the centenary of the CNT, he went to Barcelona as a guest. “So, Felix, keep going to all the sites that call you, right?” "Of course! On Monday I am taken to Madrid, as in Buenos Aires, where the CNT claims for the victims of the dictatorship. I keep going, but now I don’t go to all the mobilizations, only occasionally, because I can’t with my legs.”

These old activists, in addition to their passion for struggle, are not lacking in humor. José Moreno continues to write letters to the newspapers. “On Wednesday came one and now I’m writing another. Are you still writing? Watch out, see if we're both imprisoned! Ha, ha, ha. Don’t care about them.” Moreno has written countless letters, most of which have been published by the newspaper Deia. “I have a great report in which I have each and every one meeting. I don't know how many I have, I write a lot."

Despite being around 100 years old, all three are still in good shape: “There’s a lot to talk about. As long as a single symbol of Franco is not standing and the victims of Franco are taken into account, there will be no peace here,” the nationalist clearly explains.

In fact, many still don't know where they buried their relatives. “Ours cannot bring flowers to cemeteries. That must not be concealed, society must know why the coup d'état took place. And here nobody says anything…”, the Biscayan has argued. With passion and energy in the blood cannot be denied: “When I speak, I get angry because there is no right. I don’t speak with hatred, I want the truth to be known.”

Gaztedia, “worse than drunk”

“Young people are good, but they are not like the old ones, they don’t have that spirit. They lack indoctrination and courage. Many are worse than drunken, with everything going on, we have to go out into the street and have all this cut off.” Padín has the very clear ideas and, as in his youth, even today, even though Hank did not respond as before, he remains the same. The demonstration against the Garoña nuclear power plant, for example, took place every year until recently: “I try to go to everyone close to home. This year I didn’t go to Garoña… for the first time. But there must be one! On Sunday there is another demonstration against what is happening. Just in case, friends always go behind me, if I fall to stay, and of course, this time I will also be present.”

Usabiaga is also not at rest. The last is that of the Republican prisoners in the Ondarreta prison in Donostia-San Sebastián. “There is still a great deal of mistrust in making clear the issue. Prudence, the fear of deepening further, continues to prevail.” The Ordiziarra also teaches lectures in schools, Euskaltegis, gaztetxes, associations… It always talks about the terrible experiences lived in war and in prison. 21 years in prison. “You have to know the truth and I will continue as long as I can.”

The dictatorship caused our protagonists to become vagrants, and along the road of life they have also made very good progress. The war, the prison and the workers’ battalions have wiped out many of their friends. Time has also devoured a lot of things in recent decades. There are no more wrestlers among us. We have a determined and committed generation that is about to disappear forever; and Padín, Moreno and Usabiaga are the last spokespeople.

They're at the end of the road, but they don't love each other. “I don’t regret anything. I would do everything again,” says Usabiaga with complete confidence. The words of Félix Padín have also been strengthened suddenly, intensified: “I see you’re not standing.” “No, no. Ha ha ha ha ha ha! As long as I can, I will continue to do so!” he replied. “And you, Joseph, will you keep fighting?”: “Until you die. Not for me, but for all who gave their lives. Nobody remembers that here. They do not stop reconciling, but they never remember the victims of Franco. No one!”

Guided by his example, even if the latter “anonymous heroes” of that cruel civil war disappear, the new generations will continue on the path of memory.

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

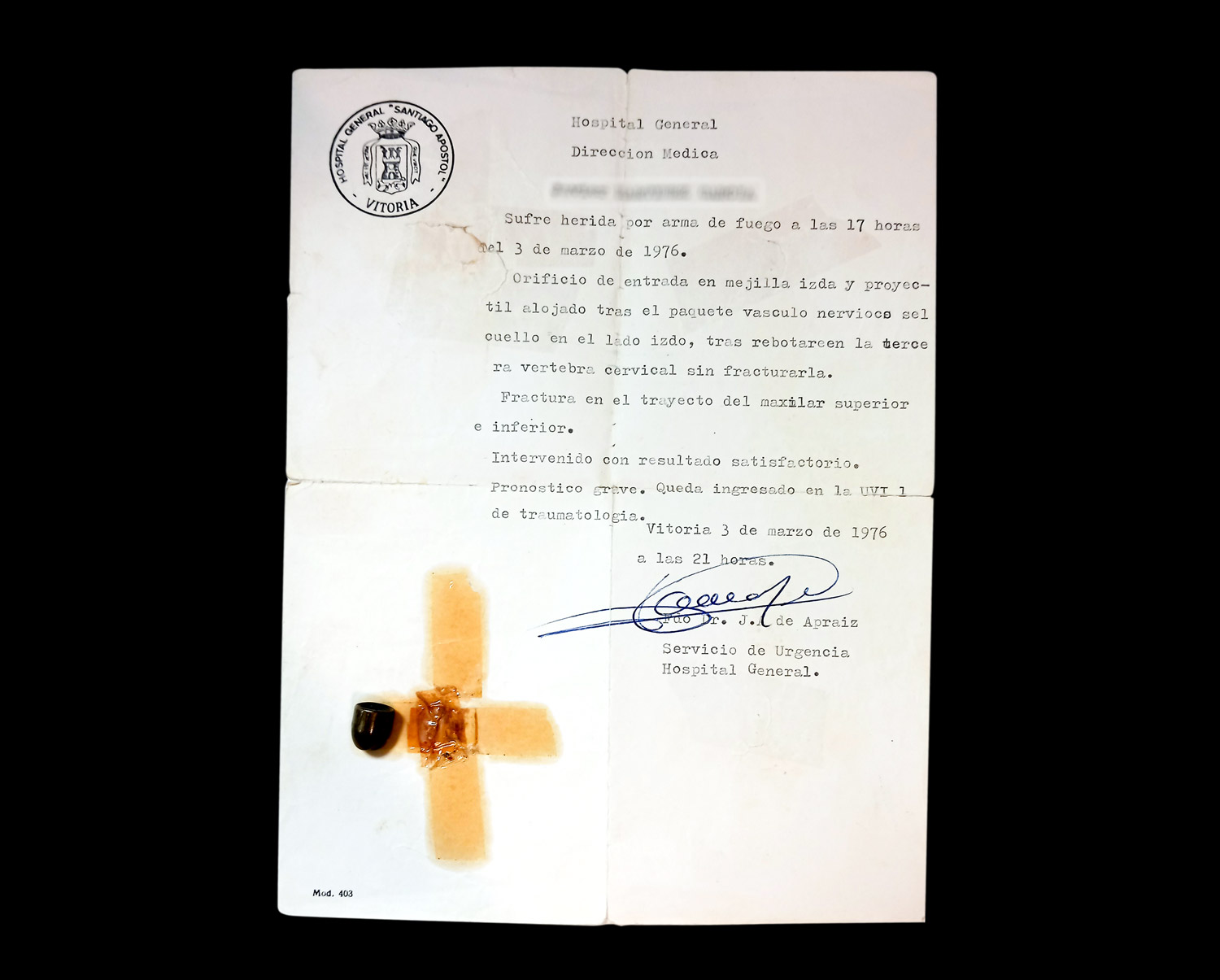

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.