The price of saying what Monsanto doesn't want to hear

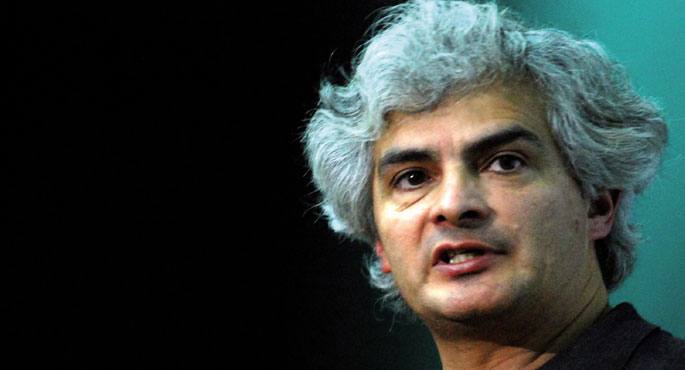

- The latest discoveries of Monsanto's transgenic maize and the herbicide Roundup have made the GM lobby move through the Gilles-Éric Séralini research. Many criticize the methodology used, “forgetting” which is the same or, in some cases, better than that used by Monsanto to obtain GM permits. It's not a new account. Many scientists have had to bear – this is not the first time for Séralin – Monsanto’s pressure in accounting for his research. Let's take a look at some examples.

In the book Le monde selon Monsanto by Marie-Monique Robin there is a chapter entitled “Manipulated scientists”. The French journalist states in a passage that one of the reasons why Monsanto has so easily imposed its products is that genetic manipulation is a complicated issue, which only scientists can understand. “The company realized that it had to control scientists to think about this issue to ensure its impact.”

As proof of this, Robin quotes an internal document from Monsanto. This is a confidential report that nobody knows how it came to the headquarters of the British association GeneWatch, which is closely following the issue of GMOs. In ten pages, the document summarizes the work done by the department of Monsanto dealing with scientific issues during the months of May and June 2000. The authors seem to be satisfied with what was achieved. Among other things, members of the Missouri company are pleased to have convinced some prestigious scientists to spread a message in favour of GMOs.

But it's an insistent science. Many independent investigations have alerted about the damage of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and in these cases, the strategy usually consists of looting the reputation of the researcher. Getting “out” of science. In short, GMO advocates want to make them believe and to a large extent get the safety of these products scientifically proven. Researchers who say otherwise will remind you not only the “bad” scientists, but also the few. This argument can be answered: firstly, there are not so many of them. And if we think that they are not so many, we can understand why, or at least one of the reasons: courage is needed to launch independent research into GMOs or, in general, that do not fit the interests of companies in the field of biotechnology. And, on the other hand, the one who has the courage will not easily get funding.

Let us see what has happened to some who have discovered in their laboratories the reverse of the truth that Monsanto opens:

“It is not fair that citizenship should be held as a tenant”

Árpád Pusztai is a Hungarian biochemist born in Hungary. In 1995, despite his retirement age, he was extended to carry out a major investigation requested by the Scottish Ministry of Agriculture, Environment and Fisheries. The first transgenic plants had just been planted in EE.UU. And the Ministry wanted to measure the impact of GMOs on human health. The aim was to give a boost to the GMOs, which were about to reach European markets. Pusztai himself was a supporter of biotechnology and began research with enthusiasm. I wanted to show that GMOs were safe.

The Pusztai team observed the effect of transgenic potatoes on rats and the results were not as expected. For starters, those potatoes weren't like normal potatoes, as they realized when they were analyzing their chemical composition. This did not coincide with the principle of equivalence of substances that has allowed GMO regulations to be so soft in the US and in many other parts of the world: in short, GMOs are equal to their counterparts roughly. It is a non-scientific principle, but it is one of the main pillars of the message for GMOs.

“Nor were transgenic potatoes equivalent to each other,” said Árpád Pusztai, “realizing this, for the first time I doubted whether genetic manipulation can be considered technology; for a classic scientist like me, technology is based on the fact that if a process has an effect, it has to have the same effect as long as the process is repeated under the same conditions.”

In spite of everything, rats had serious health problems feeding on transgenic potatoes. They interviewed Pusztai on the BBC and, although he could not reveal the details of the investigation – it was not yet published – he said a phrase that he was going to launch a big campaign against him, when they asked him if he would eat transgenic potato: “No, as a scientist who is working in this field, I think it is not fair for British citizens to recognise themselves as useless.” The accrued fame was over for decades and the position at the Rowett Institute was over. Two days later, the same ones who had congratulated him on his brilliant research into potatoes with a call from Washington to London informed him of his dismissal.

Today, the pro-GM lobby, including several scientists, tells everyone who asks questions, that in the Pusztai study there were serious methodological errors.

Transgenic contamination in Mexico

Ignacio Chapela is a Mexican biologist who works at the Berkeley University of California. He had to do some experiments on GMOs in the presence of his students and decided to use Mexican maize as a control to compare with transgenic maize, which is the purest corn in the world. However, it found transgenic DNA in several specimens from Mexico. Surprised, he began an investigation to test the contamination of Mexican maize. And he confirmed it. The results were transferred to the Mexican Government, which also carried out its own investigation, with the same result.

The discoveries of the chapel brought grave consequences to Monsanto. Not so much because of the contamination, but because of the location of the transgenic DNA fragments: they were randomly located in the genome of the contaminated plants. This means, in Chapela’s words, that although GMO manufacturers say otherwise, genetic manipulation is not stable.

Murphy and Andura Smetace received signed e-mails with the names of alleged scientists to the web of an GMO support association (AgBioWorld). Ultimately, Chapela was accused of being an activist rather than a scientist and of the result of her research being very biased. Soon, these emails came to the computers of thousands of scientists through AgBioWorld's mailing lists.

Mary Murphy and Andura Smetace do not exist, as Guardian journalist George Monbiot showed. One of the emails was sent by Monsanto itself and the other by the communications company Bivings, which operates for Monsanto. Their specialty is pressure over the Internet.

Recognize that they do the job well. Natura published an extraordinary editorial on 4 April 2002, in which it stated that Chapela’s article should never be published. There was insufficient evidence to justify the conclusions obtained by the Mexican scientist. It did not seem to matter to him that a month earlier two groups of researchers had ratified the results of the Chapela in the journal Science.

Burroughs, Chopra, Malatesta.

There are more examples. We would fill an entire journal if we explained each case with the necessary details, but it is worth mentioning some so that the reader who remains curious can use them as clues.

The first product that Monsanto genetically engineered was not a plant, but a hormone: the cow growth hormone, better known as rBST or rBGH. Injecting cows increases milk production. Well, two scientists lost their jobs by showing the damage to human health and rBST cows: Richard Burroughs, former FDA veterinarian (food marketing agency in the United States), and Shiv Chopra, former Canarian Health Service microbiologist. Cow growth hormone is banned in countries such as Canada and the European Union, among others.

In 2000, Italian researcher Manuela Malatesta from the University of Urbino repeated in her laboratory a Monsanto experiment with transgenic soy. Mice who ate that soy, unlike Monsanto's research, had health problems. Malatesta was withdrawn from the aid to continue its investigation.

Etc.

Double criteria before studies

Faced with the wave of criticism being received by Gilles-Éric Séralini in recent weeks, the association ENSSER (Network of Environmental Scientists and the Society of Social Sciences) has issued a statement. On the one hand, to ratify the scientific value of Sérali's study on transgenic maize. On the other hand, for a clear complaint: industry and associated scientists are hampering the development of appropriate methodologies for the analysis of GMOs, rather than accepting the principle of equivalence of substances by regulators. Finally, they stressed that criticism of Séralin is part of an organised campaign, in which they have actively participated. They say that the EU Food Safety Agency, and not only the EU Food Safety Agency, only rigorously evaluates studies showing negative effects of GMOs, and recognises others without going too far.

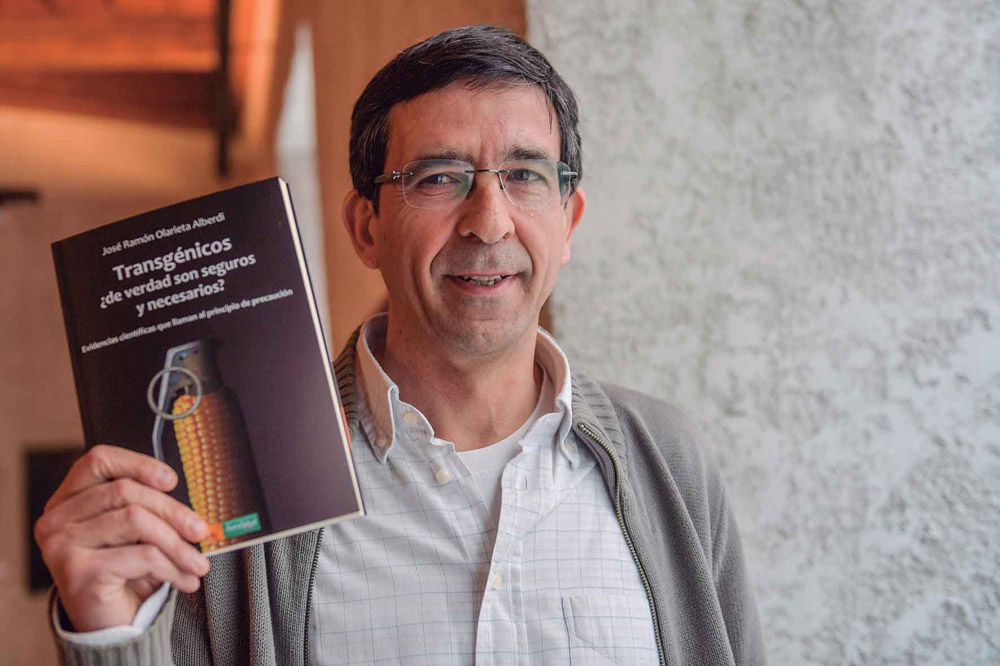

José Ramón Olarieta Alberdi is a doctor in agronomist engineering and professor at the University of Lleida, as well as a member of the Catalan association Som what Sembrem.El last year published a book on transgenics: Are GMOs really safe and necessary? In April, Leitza and... [+]

Laborantza-industrian egin den inoizko akordiorik handiena gelditzeko eskatu diote milioi bat lagunek Europari: Monsanto eta Bayer enpresek indarrak batuko dituzte galarazi ezean. Hazi transgenikoen eta industria farmazeutikoaren arteko lotura 2016tik datorren arren, azken... [+]

Europako Batzordeak iragarri du sakon aztertu nahi duela Bayer konpainiak Monsanto erosteak kalterik egingo ote dion pestiziden eta hazien merkatuari. Bruselak adierazi du fusio-operazioa burutzeak bi arlo horietako munduko enpresarik handiena sortuko lukeela, eta horrek... [+]