"Mexicans are beginning to recognize that Mexico has linguistic diversity."

- Javier López Sánchez (Oxchujk’, Chiapas, 1968) is the director of the National Institute of Indigenous Languages of Mexico (INALI). He has been in the office for two years and has recently been in the Basque Country, making the indigenous languages known. The Basque country has another mirror in which to look at itself.

Eleven language families, 68 languages, 364 variants. About seven million Mexicans speak some indigenous language, about one million are monolingual in the indigenous language. Do you have the right to live in your own language, is it a real right, or is it a burnt paper?

It is a legal claim, above all. The claim was made in 2001, and it is laid down in our Constitution. The main language rights law of indigenous peoples was done in 2003. We just started working.

What obstacles do you have when it comes to making the claim?

Resources and social awareness must go hand in hand. Awareness of both indigenous and indigenous people. In fact, indigenous languages have been considered as a dialect without value, so we must change the mentality of Mexican society so that indigenous languages are truly considered as languages, as you see in Spanish. This requires campaigns and campaigns on television and other media, and it is essential to have money. And we don't have it! However, we are not standing.

Where to start, how to act, being 68 indigenous languages in Mexico?

For example, when the presidential elections were held, we were only able to put on television eight of the 68, supported by the law. We chose some of the languages with the highest number of speakers, but also some with the lowest number of speakers. The aim was to achieve balance.

What indigenous languages are used in education?

All in one place and in one place. The project we've launched is called Intercultural Bilingual Education. In the establishment of education in indigenous peoples, we are working, together with teachers, to enable children to learn their indigenous language, learning Spanish as a second language. We are still working on this, creating a methodology for teaching indigenous languages.

At the institute you have also taken up the work to normalize the writing of indigenous languages.

We want all languages to have rules for writing. Right now, we've set the rules for writing eight languages. We work with indigenous peoples, accompanied by indigenous and non-indigenous experts, but it is the speakers themselves who decide how it will be written in their language with the help of experts. We are currently working with 16 languages. We will need one and a half years to finish this work. There is therefore much to be done. We're looking for financial resources to get more researchers to work, to speed up work, to consolidate the scriptures in all languages, because the rest of the studies are going to slow us down.

There is something about the social prestige of the indigenous language.

We want to contradict the idea of “small languages” and “large languages” so that society can value indigenous and Spanish languages equally. We want to bring the use of indigenous languages to all areas of public and institutional life, both in the media and in health, at work, in justice, etc. We've just begun. In the elections, for example, the Mayan language of Yucatán was used in the campaign and, after believing, the Mayans did not get angry! They listened to their language on television and were happy. They also enjoyed some that weren't Maia. “Without going to Yucatan, I have heard the Mayan language. Great!” Prestige, I mean. The aim is for indigenous languages also to be used in shops and banks, but much remains to be done. Internet, cyberspace -- that's also there. The work is immense. We have also held a meeting with Google to make the search engine also in indigenous languages. We're there.

Are indigenous languages alive?

There's everything. We have said that there are 364 language varieties, 64 of which are in danger of extinction, because there is no community where those languages can be spoken, that is, there are only a few speakers left, less than 100 speakers left. There are languages that only have two speakers, 15, 36 speakers… On the other side there are languages that have 1,500,000 speakers, such as the naua; the Mayan language has more than 800,000 speakers; the Zapotec languages, misteco, celtal maia – my language – and the Tzotziles… 364 languages that have no pearl to be lost in an instant, but very few are threatened in the houses and in use.

Does the Institute equally protect all languages?

No, of course not. For those with fewer speakers, we're documenting the language, especially making recordings to capture the sound of languages. We also remember the revitalization of the language so that adults can teach the youngest to speak in their own language. In the case of languages of greater vitality, we are promoting the public use of language, the creation of debates, literary representations, teaching materials. So, as the case may be.

What is the linguistic awareness of linguistic communities?

Language. We have recently worked with the Instituto del Padrón to collaborate in the questionnaire that they make up. Among other things, we have asked people about language. Well, in the 2005 census, 10 million were indigenous or at least 12 million people considered indigenous. To this day, the questions we have in the census amount to sixteen million people in this situation. You have a first level of linguistic awareness. It’s another thing to speak the language… In addition, we’ve got people who said they didn’t speak the indigenous language now to recognize that they know how to speak. That is what has happened to us in the state of Tabasco, in the south, where before the last census there were only two Ayapaneco speakers, while now there are twenty-one people who declare Ayapaneco, even if they do not speak the language.

How does the non-indigenous population of Mexico understand indigenous languages?

The National Anti-Discrimination Council (CNT) has conducted a study among Mexicans to learn about their perception of indigenous peoples and points out that people today have another sensitivity that they did not have before. To begin with, they have begun to recognize that Mexico has linguistic diversity and that Euskera is innate. In 2001, Mexico declared itself a multicultural and multilingual country, in the Constitution. This has also made Mexicans aware of this diversity and, at times, also recognize it.

If it is a committee against discrimination, it means that there is discrimination.

It is not general, there is still discrimination against indigenous people, against those who speak an indigenous language, but something is changing, both in indigenous people and in society in general. However, awareness must be increased.

Your language is Maia tzeltal.

In Chiapas, the number of speakers stood at 800,000. Now we're 1,200,000. Today, many young people form indigenous music groups and sing pop, rock, reggae or mariachi. They're an example of consciousness, a way of knowing oneself in a certain way. In last year's presidential elections, within the 132 movement, young people decided to use social networks through indigenous languages. Awareness is growing in both serious and young people. INALI is also organizing national conferences of indigenous youth so that they can discuss the importance of language in education, justice, work, gender equality, social networks, the Internet… We organize these youth conferences because we want to know what young people say about the use of their language to make decisions accordingly. Young people are very important because they hinge between young children and parents. Many parents have renounced the indigenous language, “it has no value”, while young people behave differently. “Our language is important!” they say.

You are from the town of Oxchujk. What's going on there?

Let me tell you that Oxchujk is the name of our country, but Spanish. That being said, it has no meaning, but if I tell you in the celtal language, Oxchujk’ (’ with that glotal) means “the country of the three knots.” There's the story, of course, of how those invaders came, that they found the natives, that they tied them to the tree, making three knots ...

You were punished in school for not doing Spanish well.

I started studying Spanish at six or seven years old. We talked about it in our community, but in school, you needed it in Spanish. The punishment had castled us. I remember a punishment that I lived in my own skin. The teacher himself was jealous, of the same ethnic group as us, but he told us that we had to speak Spanish well. It made us repeat words and once I dared to say ‘r’. Well, instead of the car I said expensive. He shook me, took my broom in my hand, made me go out to the yard, raised my hand and in the sun made me repeat the car a hundred times for me to learn. I could not, however, because the ‘r’ did not appear in the alphabet of my language. My voice apparatus didn't know him.

Your language was therefore Celtic.

In childhood, in the family, in the community, in coexistence, in the river, in the countryside… indigenous language, the Celtic. In school, Spanish. In Elementary we were allowed, in part, to use Celta, but before High, we had to discard it to reach the next levels without talking to Celta. We arrived at university with a totally abandoned indigenous language. The society of San Cristobal de las Casas is very discriminatory, racist, and I demonstrated it wholeheartedly. In school and out of school. The indigenous people and not the indigenous people, including the mestizos, made fun of us by not pronouncing Spanish well or by using the Celtic syntax. I think the same thing happened in Euskal Herria…

There is a book written two years ago by Koldo Izagirre, who has been in charge of the autopsy tests. In Spanish, or with celts!, if there were, you would know… Is Tzeltala alive in Oxchujk today?

Very alive, but it's also true that many children, many young people, don't speak celtic. Many others do. However, there are many teachers who work to reclaim the language, and in summer they organized celtal courses, for example. That's in Oxchujk, my hometown.

Mexikoko bi emakume hauen bizitzak indarkeriak eta desplazamenduak zeharkatzen ditu. Haien familiako edo komunitateko kideak hiltzen ikusi dituzte, eta krimen antolatuak zabaltzen duen terrorea azalean sentitu dute; mehatxuak, jazarpena... ohiko dituzte. Baina horrek guztiak... [+]

It was impossible to guess who was or who was the motto I read, but who was!

Ángel González Olvera was known in Mexico 11 years ago when the bertsolaris invited us to a few days with their improvisers. He lived on a high hill, feeding on birds, pigeons, pigeons, hedgehogs,... [+]

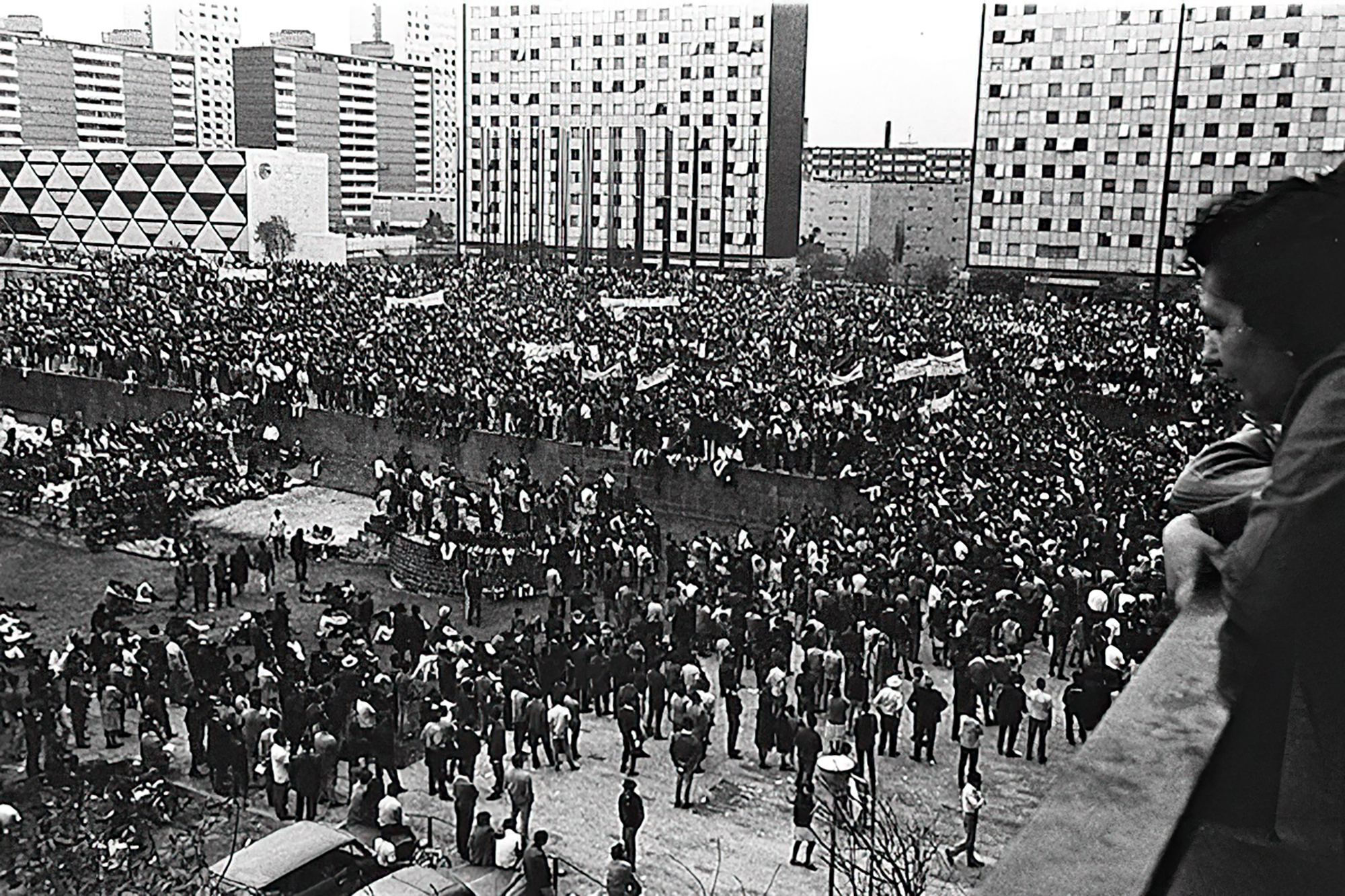

Born 2 October 1968. A few months earlier, the student movement started on June 22 organized a rally in the Plaza de las Tres Cultura, in the Nonoalco-Tlatelolco unit of the city. The students gathered by the Mexican army and the paramilitary group Olympia Battalion were... [+]

In the desert of Coahuila (Mexico), in the dunes of Bilbao, remains of a human skeleton have been found. After being studied by archaeologists, they conclude that they are between 95 and 1250 years old and that they are related to the culture of Candelaria.

The finding has been... [+]